Secretive Victorian Artists Made These Intricate Patterns Out of Algae

A new documentary profiles Klaus Kemp, the sole practicioner of a quirky art form that is invisible to the naked eye

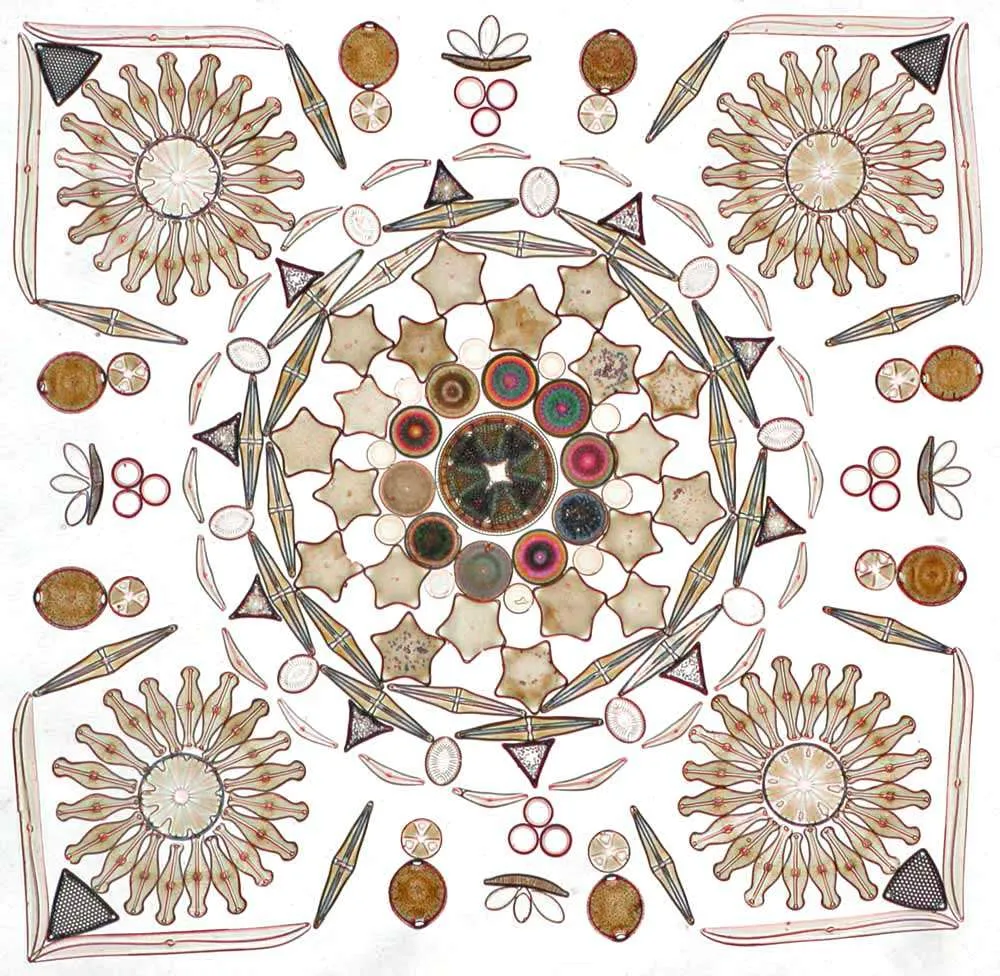

Since seeing his first diatom arrangement—an intricate pattern of algae crafted by German microscopist J.D. Möller—Matthew Killip has been enthralled with the Victorian art form. "I love seeing the hand of man display the work of nature so beautifully," he says.

Almost immediately, the British filmmaker had two questions. First, how did these 19th-century artists manage to assemble diatoms, each just microns long, into dazzling shapes invisible to the naked eye? And secondly, is anyone still working in this medium?

Killip's search for answers led him to Klaus Kemp, the only living practicioner. He spent an afternoon with the eccentric Englishman, cameras rolling, and produced the documentary, seen above, called "The Diatomist." The short film was released this week.

I interviewed Killip by email to find out more about this lost art:

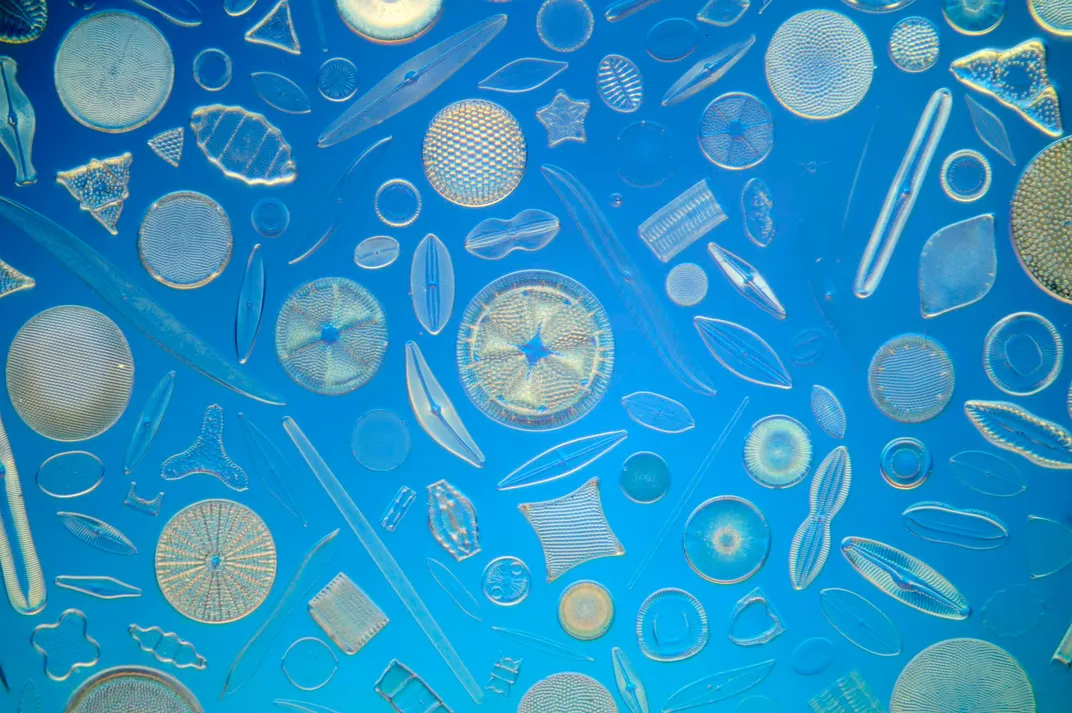

What exactly is a diatom?

Diatoms are microscopic single-cell algae housed in beautiful glass shells. There are hundreds of thousands of varieties of diatoms all with unique forms.

So when and how did diatom arrangement emerge as an art form?

The first diatom arrangements date back to the early 1800s, but the art form reached its peak in the latter part of the century. It was a period of intense interest in the natural world and also a time when the arts and sciences were more closely aligned. Diatom arrangements are a stunning example of that particularly Victorian desire to bring order to the world, to display nature in a rational way.

Can you give us a sense of the scale here? How small are these arrangements?

Diatoms range in size from 5 microns to 200 microns. A micron is one-thousandth of a millimeter. A diatom arrangement of 100 forms would fit inside a punctuation mark of average-size text.

How was the art viewed and shared?

Arrangements were often made by professional microscopists, such as J.D. Möller (1844 - 1907). They were sold alongside other miniature curiosities, including microscopic photographs, to wealthy amateur naturalists who would exhibit them at social gatherings as an amusement.

How did Klaus Kemp become a diatomist?

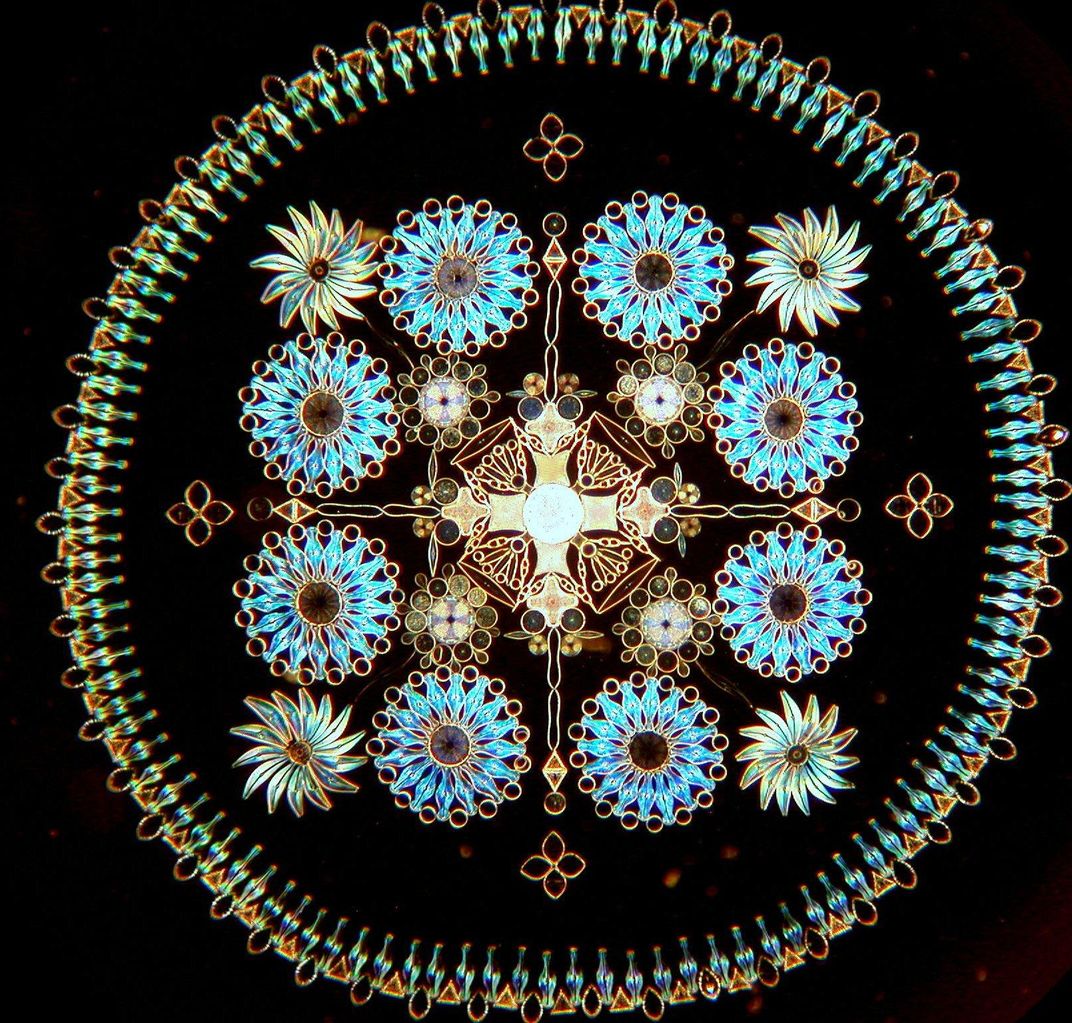

Klaus saw his first diatom arrangement at age 16. Instantly smitten, he set about trying to replicate what he had seen. It took Klaus eight years of experimentation before he was able to make a comparable arrangement.

Is he self-taught?

Klaus is, by necessity, self-taught. The diatomists of the Victorian period were in competition with each other and never accurately revealed the secrets of their techniques—all their methods went to the grave with them. With no reliable information to work from, Klaus spent years researching and experimenting with glue to find the perfect solution with which to mount diatoms. Klaus' particular formula is currently known only to him, though his wife has been instructed to release the recipe once he passes away.

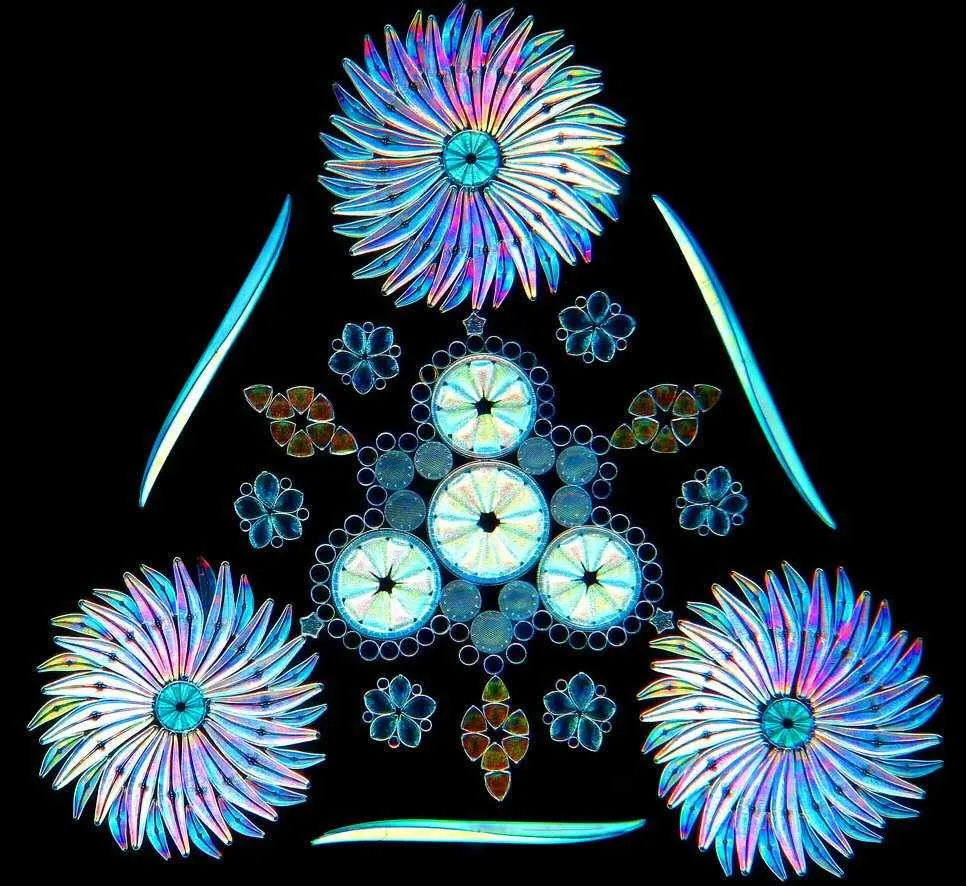

Where does he collect diatoms? And what, specifically, is he looking for?

Diatoms can potentially be found in any body of water—puddles, lakes, rivers or the sea. Klaus is forever scrabbling around in some ditch or by the shore looking for new specimens, and he has collected samples from around the world. He is also in correspondence with many foreign diatom enthusiasts who often provide him with specimens from other countries. Although Klaus is crazy about all diatoms, he has specialized in the genus Mastogloia—they are his true passion. Klaus has also discovered several new species.

How does Kemp actually arrange the diatoms? What does the process look like?

After the diatoms have been cleaned, they are placed on a glass slide with adhesive. They can then be manipulated under a microscope for a period of time—as long as the glue will allow. Klaus has a unique glue formula that allows him to work over a period of days, enough time to make exceptionally complex arrangements. Once the glue has set, a high refractive index mountant is added. This allows the diatoms to be seen more clearly. Finally, another glass slide is placed on top to protect the arrangement.

You have to be a little mad to do this kind of work, don't you think?

Klaus freely admits a tinge of obsession is necessary.

What do you like about these arrangements?

I find the best arrangements overwhelming. The variety and intricacy of shapes, patterns and repetitions evoke a profound sense of awe. I can't help but recall Darwin: "Endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)