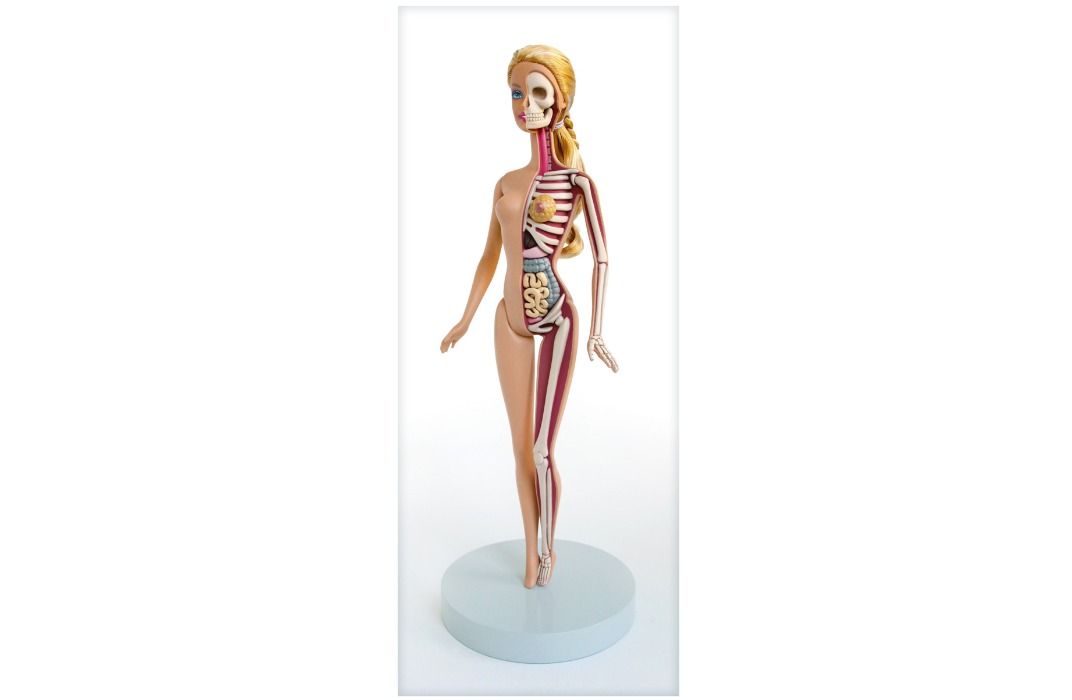

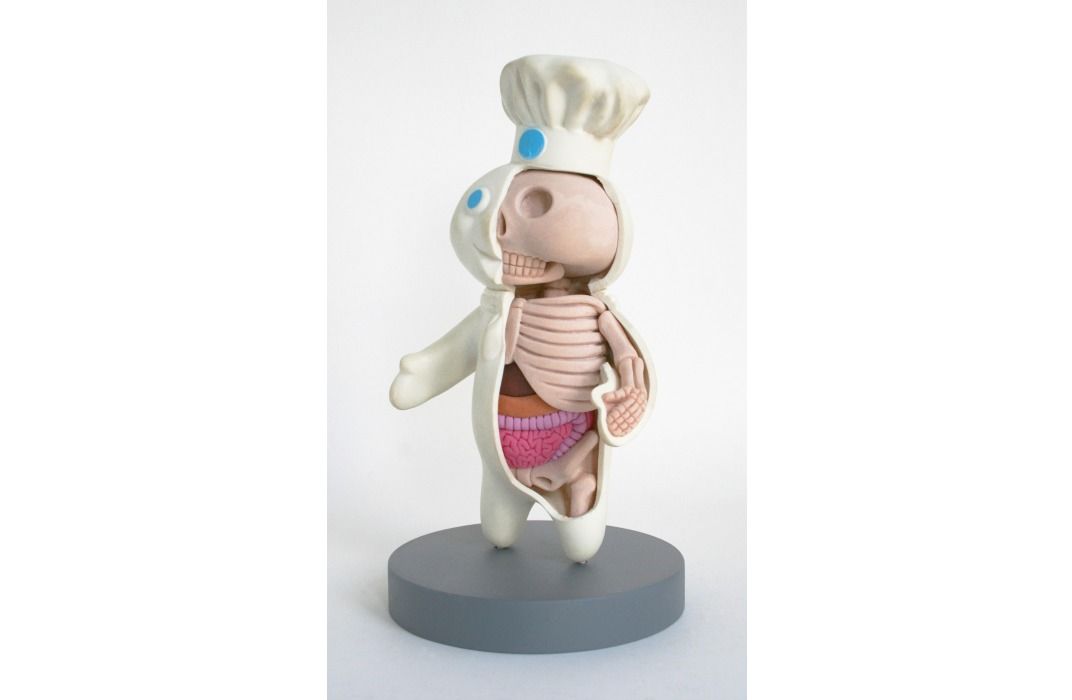

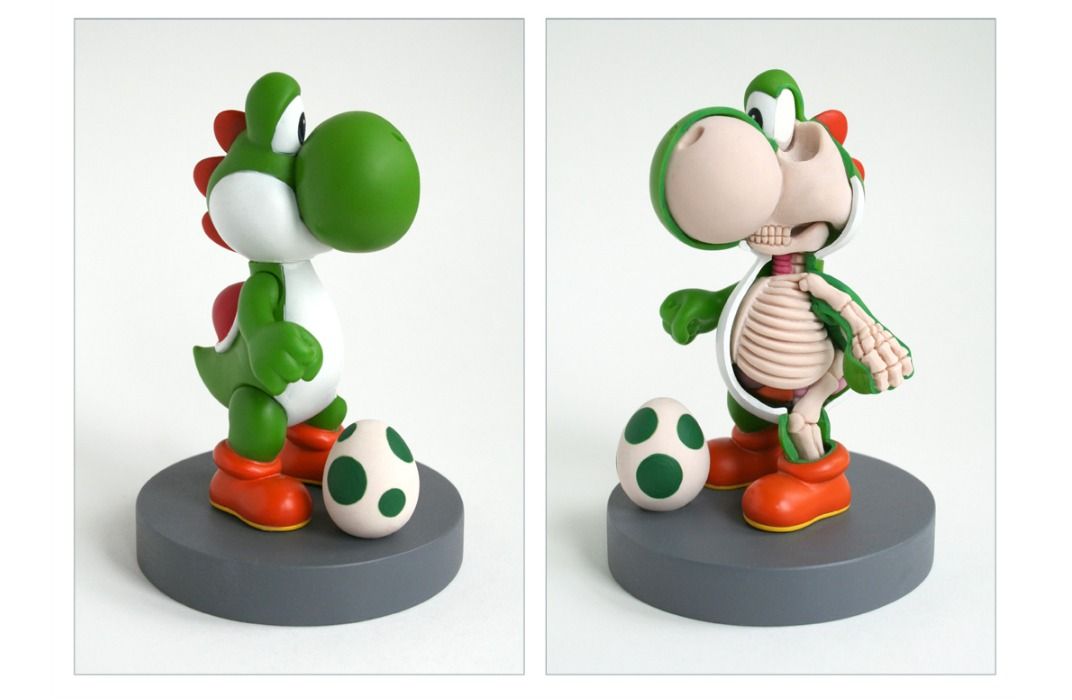

See the Inner Anatomy of Barbie, Mario and Mickey Mouse—Bones, Guts and All

Artist Jason Freeny transforms familiar childhood characters into realistic anatomical models

Oftentimes, when parents first see Jason Freeny's sculptures that reveal the inner anatomy of cherished childhood toys, they get a little worried that their children will be disturbed. Most kids, though, have a rather different reaction.

"Kids aren't scared by them. They're fascinated," says Freeny, the New York-based artist who's hand-sculpted hundreds of these inner anatomies, built into commercially-available toys, over the last seven years. "I believe that being frightened by inner anatomy is a learned thing. It's something that's taught to kids by society, rather than something that's innate."

Freeny himself responds to supposedly morbid anatomical features—like, say, a Lego's intestines, or Mario's lungs—the same way kids generally do. "I love anatomy," he says. "As an artist, I've always been a big fan of drawing organic shapes, because of their complex detail."

Freeny, who now creates the sculptures and other art full-time, documenting their creation on his Facebook page, began working on the project in 2007 on the side, while he still worked his day job as a designer at a tech startup. It began when, while digitally illustrating a balloon animal, he decided to try his hand at drawing its inner anatomy. "I started by drawing its skeleton system, and I was just fascinated by the completely grotesque skeletal system that its shape was dictating to me," he says.

After illustrating the innards of several other characters (including a gummy bear), his startup closed, and he was laid off. Eventually, he moved from his 600-square-foot Manhattan apartment to Long Island—where he had enough space in the garage to do some sculpting—and embarked on his first 3D anatomy project. "I started cutting into a little Dunny toy, and decided to give it a clay skeleton anatomy," Freeny says. "That's when it all really took off."

In the years since, Freeny has anatomically-supplemented dozens of different characters from video games, movies and even brand advertisements. For each sculpture, he begins by buying a high-quality toy ("If it's a crappy toy to begin with, the sculpture is going to end up looking crappy too," he says), then cuts away a portion of it. Using clay, he sculpts the character's bones and a few internal organs, then paints them what he imagines to be realistic colors. Working on several pieces at a time, he completes about four or five per month, and sells the hand-built sculptures on his website along with his other artworks.

Hypothesizing the proportion of each character's innards is the trickiest part. "It's like a reverse forensics project," Freeny says. "The exterior shape dictates what the skeleton looks like."

He generally uses scientific illustrations to make the sculptures as accurate as possible. However, because the characters themselves are fictional, that's sometimes impossible. "Mickey Mouse, for example, is a mouse, but he walks upright, like a person," he says. "So his body, like many characters, ends up being more of a version of a human skeleton, distorted to fit inside the character. It's a balancing act."

One of Freeny's current projects—Sid, the sloth from Ice Age—has proven to be particularly difficult. "His body's just very extreme, and cartoony," he says. "At first, I was approaching him as a human, and it just wasn't working, so I used some sloth anatomy proportions. Almost the entire length of their bodies are ribcage, which solved a lot of anatomical problems for me."

Initially, Freeny was unsure what reactions his unconventional work would garner, but they've been overwhelmingly positive. In some cases, he's even gotten praise from the creators and manufacturers of the characters (although he's also had a couple of corporate legal teams tell him to stop making the sculptures, alleging intellectual property infringement).

Although he recognizes the value of his sculptures as tools for scientific education—and has seen his own kids learn from the dozens of pieces lying around his workshop—his original intention was never to teach anyone anatomy. "I just love exploring these characters, and seeing what they look like inside," Freeny says. "I want to see the grotesque, weird anatomies that these toys dictate."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)