Sherlock Holmes’ London

As the detective stalks movie theaters, our reporter tracks down the favorite haunts of Arthur Conan Doyle and his famous sleuth

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/London-England-Houses-of-Parliament-631.jpg)

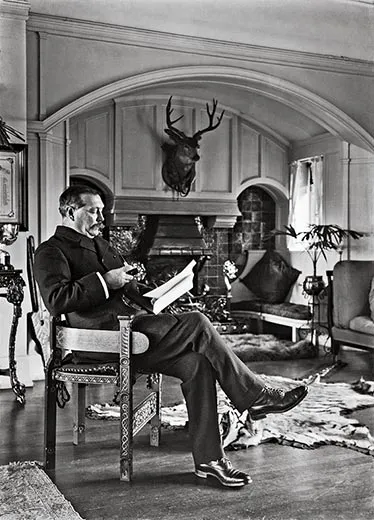

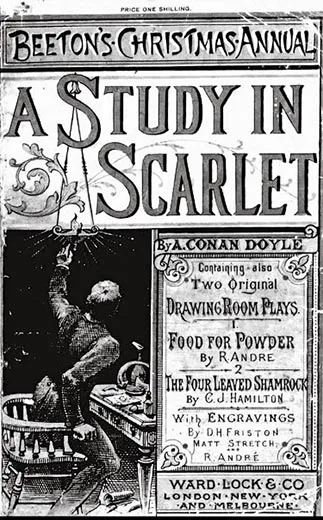

One summer evening in 1889, a young medical school graduate named Arthur Conan Doyle arrived by train at London’s Victoria Station and took a hansom cab two and a half miles north to the famed Langham Hotel on Upper Regent Street. Then living in obscurity in the coastal town of Southsea, near Portsmouth, the 30-year-old ophthalmologist was looking to advance his writing career. The magazine Beeton’s Christmas Annual had recently published his novel, A Study in Scarlet, which introduced the private detective Sherlock Holmes. Now Joseph Marshall Stoddart, managing editor of Lippincott’s Monthly, a Philadelphia magazine, was in London to establish a British edition of his publication. At the suggestion of a friend, he had invited Conan Doyle to join him for dinner in the Langham’s opulent dining room.

Amid the bustle of waiters, the chink of fine silver and the hum of dozens of conversations, Conan Doyle found Stoddart to be “an excellent fellow,” he would write years later. But he was captivated by one of the other invited guests, an Irish playwright and author named Oscar Wilde. “His conversation left an indelible impression upon my mind,” Conan Doyle remembered. “He had a curious precision of statement, a delicate flavour of humour, and a trick of small gestures to illustrate his meaning.” For both writers, the evening would prove a turning point. Wilde left with a commission to write his novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray, which appeared in Lippincott’s June 1890 issue. And Conan Doyle agreed to produce a second novel starring his ace detective; The Sign of Four would cement his reputation. Indeed, critics have speculated that the encounter with Wilde, an exponent of a literary movement known as the Decadents, led Conan Doyle to deepen and darken Sherlock Holmes’ character: in The Sign of Four’s opening scene, Holmes is revealed to be addicted to a “seven-percent solution” of cocaine.

Today the Langham Hotel sits atop Regent Street like a grand yet faded dowager, conjuring up a mostly vanished Victorian landscape. The interior has been renovated repeatedly over the past century. But the Langham’s exterior—monolithic sandstone facade, with wrought-iron balconies, French windows and a columned portico—has hardly changed since the evening Conan Doyle visited 120 years ago. Roger Johnson, publicity director of the Sherlock Holmes Society of London, a 1,000-strong band of Holmes devotees, points to the hotel’s mention in several Holmes tales, including The Sign of Four, and says it’s a kind of shrine for Sherlockians. “It’s one of those places where the worlds of Conan Doyle and Sherlock Holmes come together,” he adds. Others include the Lyceum Theatre, where one of Conan Doyle’s plays was produced (and a location in The Sign of Four), as well as the venerable gentlemen’s clubs along the thoroughfare of the Strand, establishments that Conan Doyle frequented during forays into the city from his estate in Surrey. Conan Doyle also appropriated St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in central London as a setting; it was there that the legendary initial meeting between Holmes and Dr. Watson took place.

Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle was born on May 22, 1859, in Edinburgh, Scotland, the son of Charles Doyle, an alcoholic who would spend much of his later life in a mental institution, and Mary Foley Doyle, the attractive, lively daughter of an Irish doctor and a teacher; she loved literature and, according to biographer Andrew Lycett, beguiled her children with her storytelling. Marking the sesquicentennial of Conan Doyle’s birth, Edinburgh held a marathon of talks, exhibitions, walking tours, plays, films and public performances. Harvard University sponsored a three-day lecture series examining Holmes’ and Conan Doyle’s legacy. This past spring, novelist Lyndsay Faye published a new thriller, Dust and Shadow, featuring Holmes squaring off against Jack the Ripper. And last month, of course, Holmes took center stage in director Guy Ritchie’s Hollywood movie Sherlock Holmes, starring Robert Downey Jr. as Holmes and Jude Law as Watson.

A persuasive case can be made that Holmes exerts just as much hold on the world’s imagination today as he did a century ago. The Holmesian canon—four novels and 56 stories—continues to sell briskly around the world. The coldly calculating genius in the deerstalker cap, wrestling with his inner demons as he solves crimes that befuddle Scotland Yard, stands as one of literature’s most vivid and most alluring creations.

Conan Doyle’s other alluring creation was London. Although the author lived only a few months in the capital before moving to the suburbs, he visited the city frequently throughout his life. Victorian London takes on almost the presence of a character in the novels and stories, as fully realized—in all its fogs, back alleys and shadowy quarters—as Holmes himself. “Holmes could never have lived anywhere else but London,” says Lycett, author of the recent biography The Man Who Created Sherlock Holmes: The Life and Times of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. “London was the hub of the empire. In addition to the Houses of Parliament, it had the sailors’ hostels and the opium dens of the East End, the great railway stations. And it was the center of the literary world.”

Much of that world, of course, has been lost. The British Clean Air Act of 1956 would consign to history the coal-fueled fogs that shrouded many Holmes adventures and imbued them with menace. (“Mud-coloured clouds drooped sadly over the muddy streets,” Conan Doyle writes in The Sign of Four. “Down the Strand the lamps were but misty splotches of diffused light which threw a feeble circular glimmer upon the slimy pavement.”) The blitz and postwar urban redevelopment swept away much of London’s labyrinthine and crime-ridden East End, where “The Man With the Twisted Lip” and other stories are set. Even so, it is still possible to retrace many of the footsteps that Conan Doyle might have taken in London, to follow him from the muddy banks of the Thames to the Old Bailey and obtain a sense of the Victorian world he transmuted into art.

He first encountered london at the age of 15, while on a three-week vacation from Stonyhurst, the Jesuit boarding school to which his Irish Catholic parents consigned him in northern England. “I believe I am 5 foot 9 high,” the young man told his aunt, so she could spot him at Euston station, “pretty stout, clad in dark garments, and above all, with a flaring red muffler round my neck.” Escorted around the city by his uncles, young Conan Doyle took in the Tower of London, Westminster Abbey and the Crystal Palace, and viewed a performance of Hamlet, starring Henry Irving, at the Lyceum Theatre in the West End. And he went to the Chamber of Horrors at Madame Tussaud’s wax museum, then located in the Baker Street Bazaar (and on Marylebone Road today). Conan Doyle viewed with fascination wax models of those who had died on the guillotine during the French Revolution as well as likenesses of British murderers and other arch-criminals. While there, the young man sketched the death scene of French radical Jean-Paul Marat, stabbed in his bath at the height of the Revolution. After visiting the museum, Conan Doyle wrote in a letter to his mother that he had been irresistibly drawn to “the images of the murderers.”

More than a decade later, having graduated from medical school in Edinburgh and settled in Southsea, the 27-year-old physician chose London for the backdrop of a novel about a “consulting detective” who solves crimes by applying keen observation and logic. Conan Doyle had been heavily influenced by Dr. Joseph Bell, whom he met at the Edinburgh Infirmary and whose diagnostic powers amazed his students and colleagues. Also, Conan Doyle had read the works of Edgar Allan Poe, including the 1841 “Murders in the Rue Morgue,” featuring inspector C. Auguste Dupin. Notes for an early draft of A Study in Scarlet—first called “A Tangled Skein”—describe a “Sherringford Holmes” who keeps a collection of rare violins and has access to a chemical laboratory; Holmes is aided by his friend Ormond Sacker, who has seen military service in Sudan. In the published version of A Study in Scarlet, Sacker becomes Dr. John H. Watson, who was shot in the shoulder by a “Jezail bullet” in Afghanistan and invalided in 1880 to London—“that great cesspool into which all the loungers and idlers of the Empire are irresistibly drained.” As the tale opens, Watson learns from an old friend at the Criterion Bar of “a fellow who is working at the chemical laboratory up at the hospital [St. Bartholomew’s],” who is looking to share lodgings. Watson finds Holmes poised over a test tube in the middle of an “infallible” experiment to detect human blood stains. Holmes makes the now-immortal observation: “You have been in Afghanistan, I perceive.” (Holmes pieces together a series of clues—Watson’s deep tan; an injury to his left arm; a background in medicine; a haggard face—to deduce that Watson had served as an army doctor there.) The physician, intrigued, moves in with Holmes into the “cheerfully furnished” rooms at 221B Baker Street.

The address is another shrine for the detective’s devotees—although, as any expert will attest, 221 Baker Street existed only in Conan Doyle’s imagination. In the Victorian era, Baker Street went up to only number 85. It then became York Place and eventually Upper Baker Street. (Conan Doyle was hardly a stickler for accuracy in his Holmes stories; he garbled some street names and invented others and put a goose seller in Covent Garden, then a flower and produce market.) But some Sherlockians have made a sport out of searching for the “real” 221B, parsing clues in the texts with the diligence of Holmes himself. “The question is, Did Holmes and Watson live in Upper Baker or in Baker?” says Roger Johnson, who occasionally leads groups of fellow pilgrims on expeditions through the Marylebone neighborhood. “There are arguments in favor of both. There are even arguments in favor of York Place. But the most convincing is that it was the lower section of Baker Street.”

One drizzly afternoon I join Johnson and Ales Kolodrubec, president of the Czech Society of Sherlock Holmes, who is visiting from Prague, on a walk through Marylebone in search of the location Conan Doyle might have had in mind for Holmes’ abode. Armed with an analysis written by Bernard Davies, a Sherlockian who grew up in the area, and a detailed 1894 map of the neighborhood, we thread through cobblestone mews and alleys to a block-long passage, Kendall Place, lined by brick buildings. Once a hodgepodge of stables and servants’ quarters, the street is part of a neighborhood that is now mainly full of businesses. In the climax of the 1903 story “The Empty House,” Holmes and Watson sneak through the back entrance of a deserted dwelling, whose front windows face directly onto 221B Baker Street. The description of the Empty House matches that of the old town house we’re looking at. “The ‘real’ 221B,” Johnson says decisively, “must have stood across the road.” It’s a rather disappointing sight: today the spot is marked by a five-story glass-and-concrete office building with a smoothie-and-sandwich take-away shop on the ground floor.

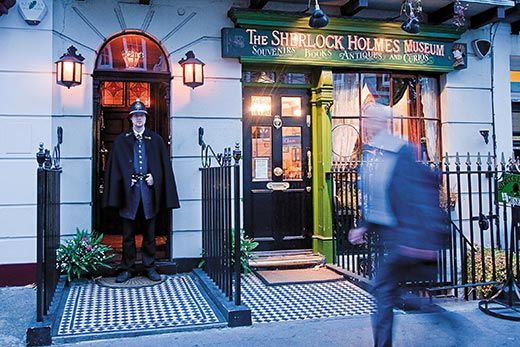

In 1989, Upper Baker and York Place having been merged into Baker Street decades earlier, a London salesman and music promoter, John Aidiniantz, bought a tumbledown Georgian boardinghouse at 239 Baker Street and converted it into the Sherlock Holmes Museum.

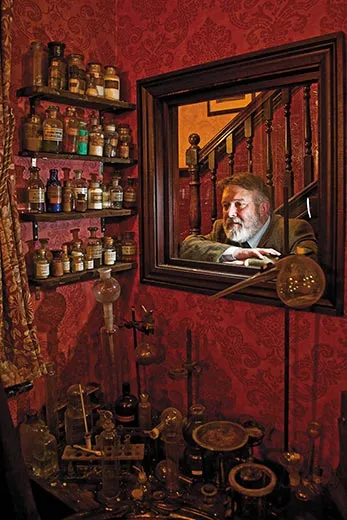

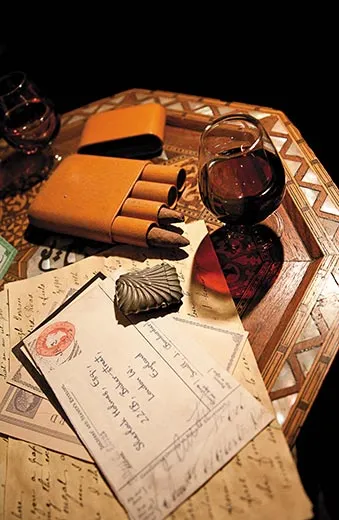

A fake London bobby was patrolling in front when I arrived there one weekday afternoon. After paying my £6 entry fee (about $10), I climbed 17 stairs—the exact number mentioned in the Holmes story “A Scandal in Bohemia”—and entered a small, shabby parlor filled with Victorian and Edwardian furniture, along with props that seemed reasonably faithful to the description of the drawing room provided by Watson in “The Empty House”: “The chemical corner and the acid-stained deal-topped table....The diagrams, the violin case, and the pipe rack.” Watson’s stuffy bedroom was one flight up, crammed with medical paraphernalia and case notes; a small exhibition hall, featuring lurid dioramas from the stories and wax figurines of Sherlock Holmes and archenemy Professor Moriarty, filled the third floor. Downstairs in the gift shop, tourists were browsing through shelves of bric-a-brac: puzzles, key rings, busts of Holmes, DVDs, chess sets, deerstalker caps, meerschaum pipes, tobacco tins, porcelain statuettes and salt and pepper shakers. For a weekday afternoon, business seemed brisk.

But it has not been a universal hit. In 1990 and 1994, scholar Jean Upton published articles in the now-defunct magazine Baker Street Miscellanea criticizing “the shoddiness of the displays” at the museum, the rather perfunctory attention to Holmesian detail (no bearskin rug, no cigars in the coal scuttle) and the anachronistic furniture, which she compared to “the dregs of a London flea market.” Upton sniffed that Aidiniantz himself possessed only superficial knowledge of the canon, although, she wrote, he “gives the impression of considering himself the undisputed authority on the subject of Sherlock Holmes and his domicile.”

“I’m happy to call myself a rank amateur,” Aidiniantz replies.

For verisimilitude, most Sherlockians prefer the Sherlock Holmes Pub, on Northumberland Street, just below Trafalgar Square, which is packed with Holmesiana, including a facsimile head of the Hound of the Baskervilles and Watson’s “newly framed portrait of General Gordon,” the British commander killed in 1885 at the siege of Khartoum and mentioned in “The Cardboard Box” and “The Resident Patient.” The collection also includes Holmes’ handcuffs, and posters, photographs and memorabilia from movies and plays recreating the Holmes stories. Upstairs, behind a glass wall, is a far more faithful replica of the 221B sitting room.

In 1891, following the breakout success of The Sign of Four, Conan Doyle moved with his wife, Louise, from Southsea to Montague Place in Bloomsbury, around the corner from the British Museum. He opened an ophthalmological practice at 2 Upper Wimpole Street in Marylebone, a mile away. (In his memoirs, Conan Doyle mistakenly referred to the address as 2 Devonshire Place. The undistinguished, red-brick town house still stands, marked by a plaque put up by the Westminster City Council and the Arthur Conan Doyle Society.) The young author secured one of London’s best-known literary agents, A.P. Watt, and made a deal with The Strand, a new monthly magazine, to write a series of short stories starring Holmes. Fortunately for his growing fan base, Conan Doyle’s medical practice proved an utter failure, affording him plenty of time to write. “Every morning I walked from the lodgings at Montague Place, reached my consulting-room at ten and sat there until three or four, with never a ring to disturb my serenity,” he would later remember. “Could better conditions for reflection and work be found?”

Between 1891 and 1893, at the height of his creative powers, Conan Doyle produced 24 stories for The Strand, which were later collected under the titles The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes and The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes. As the stories caught on, The Strand’s readership doubled; on publication day, thousands of fans would form a crush around London bookstalls to snap up the detective’s latest adventure. A few months after arriving in London, the writer moved again, with his wife and his young daughter, Mary, to Tennison Road in the suburb of South Norwood. Several years later, with his fame and fortune growing, he continued his upward migration, this time to a country estate, Undershaw, in Surrey.

But Conan Doyle, a socially and politically active man, was drawn repeatedly back to the bustle and intercourse of London, and many of the characters and places he encountered found their way into the stories. The Langham, the largest and by many accounts best hotel in Victorian London, was one of Conan Doyle’s haunts. Noted for its salubrious location on Upper Regent Street (“much healthier than the peat bogs of Belgravia near the River Thames favored by other hoteliers,” as the Langham advertised when it opened in 1865) and sumptuous interiors, the hotel was a magnet for British and American literati, including the poets Robert Browning and Algernon Swinburne, the writer Mark Twain and the explorer Henry Morton Stanley before he set out to find Dr. Livingstone in Africa. It was at the Langham that Conan Doyle would place a fictional king of Bohemia, the 6-foot-6 Wilhelm Gottsreich Sigismond von Ormstein, as a guest. In “A Scandal in Bohemia,” published in 1891, the rakish, masked Bohemian monarch hires Holmes to recover an embarrassing photograph from a former lover. “You will find me at The Langham, under the name of Count Von Kramm,” the king informs the detective.

Another institution that figured both in Conan Doyle’s real and imagined life was the Lyceum Theatre in the West End, a short walk from Piccadilly Circus. Conan Doyle’s play Waterloo had its London opening there in 1894, starring Henry Irving, the Shakespearian thespian he had admired two decades earlier during his first London trip. In The Sign of Four, Holmes’ client, Mary Morstan, receives a letter directing her to meet a mysterious correspondent at the Lyceum’s “third pillar from the left,” now another destination for Sherlockians. Conan Doyle was an active member of both the Authors’ Club on Dover Street and the Athenaeum Club on Pall Mall, near Buckingham Palace. The latter served as the model for the Diogenes Club, where Watson and Holmes go to meet Holmes’ older brother, Mycroft, in “The Adventure of the Greek Interpreter.”

Although Holmes made his creator wealthy and famous, Conan Doyle quickly wearied of the character. “He really thought that his literary vocation was elsewhere,” says Lycett, the biographer. “He was going to be somebody a bit like Walter Scott, who would write these great historical novels.” According to David Stuart Davies, who has written five Holmes mystery novels and two one-man shows about Holmes, Conan Doyle “wanted to prove that he was more than just a mystery writer, a man who made puzzles for a cardboard character to solve. He was desperate to cut the shackles of Sherlock from him,” so much so that in 1893, Conan Doyle sent Holmes plummeting to his death over the Reichenbach Falls in Switzerland along with Professor Moriarty.

But less than a decade later—during which Conan Doyle wrote a series of swashbuckling pirate stories and a novel, among other works, which were received with indifference—popular demand, and the promise of generous remuneration, eventually persuaded him to resuscitate the detective, first in the masterful novel The Hound of the Baskervilles, which appeared in 1901, then in a spate of less well-regarded stories that he continued writing until he died of a heart attack in 1930 at age 71. In addition to the Holmes stories, Conan Doyle had written some 60 works of nonfiction and fiction, including plays, poetry and such science-fiction classics as The Lost World, and amassed a fortune of perhaps $9 million in today’s dollars. “Conan Doyle never realized what he’d created in Sherlock Holmes,” says Davies. “What would he say today if he could see what he spawned?”

Late one morning, I head for the neighborhood around St. Paul’s Cathedral and walk along the Thames, passing underneath the Millennium Bridge. In The Sign of Four, Holmes and Watson set off one evening on a “mad, flying manhunt” on the Thames in pursuit of a villain escaping in a launch. “One great yellow lantern in our bows threw a long, flickering funnel of light in front of us,” Conan Doyle wrote. The pursuit ends in “a wild and desolate place, where the moon glimmered upon a wide expanse of marshland, with pools of stagnant water and beds of decaying vegetation.” Today the muddy riverbank, with rotting wooden pilings protruding from the water, still bears faint echoes of that memorable chase.

I cross St. Paul’s churchyard, wind through alleys and meet Johnson in front of the stately Henry VIII gate at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital. Founded in 1123 by a courtier of Henry I, Barts is located in Smithfield, a section of the city that once held a medieval execution ground. There, heretics and traitors, including the Scottish patriot William Wallace (portrayed by Mel Gibson in the film Braveheart), were drawn and quartered. The square is surrounded by public houses—one half-timbered structure dates to Elizabethan times—that cater to workers in the Smithfield meat market, a sprawling Victorian edifice with a louvered roof where cattle were driven and slaughtered as late as the 1850s. In the hospital’s small museum, a plaque erected by the Baker Street Irregulars, an American Holmesian group, commemorates the first meeting of Holmes and Watson in the now-defunct chemistry lab.

We end up in Poppins Court, an alley off Fleet Street, which some Holmes followers insist is the Pope’s Court in the story “The Red-Headed League.” In that comic tale, Holmes’ client, the dim-witted pawnbroker Jabez Wilson, answers a newspaper ad offering £4 a week to a man “sound in body and mind” whose only other qualifications are that he must have red hair and be over 21. Wilson applies for the job, along with hundreds of other redheads, in an office building located in an alley off Fleet Street, Pope’s Court. “Fleet Street,” wrote Conan Doyle, “was choked with red-headed folk, and Pope’s Court looked like a coster’s [fruit seller’s] orange barrow.” The job, which requires copying out the Encyclopaedia Britannica for four hours a day, is a ruse to keep Wilson from his pawnshop for eight weeks—while thieves drill into the bank vault next door. Studying a 19th-century map of the district as the lunchtime crowd bustles past us, Johnson has his doubts. “I don’t think Conan Doyle knew about Poppins Court at all, but it’s very convenient,” he says.

Conan Doyle, adds Johnson, “simply invented some places, and what we’re doing is finding real places that could match the invented ones.” Holmes’ creator may have exercised artistic license with London’s streets and markets. But with vivid evocations of the Victorian city—one recalls the fog-shrouded scene Conan Doyle conjures in A Study in Scarlet: “a dun-coloured veil hung over the house tops, looking like the reflections of the mud-coloured streets beneath”—he captured its essence like few other writers before or since.

Writer Joshua Hammer lives in Berlin. Photographer Stuart Conway is based in London.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)