Start Hoarding Your Beans, Thanks to Climate Change, $7 Coffee May Be the Norm

Starbucks most expensive cup of coffee to date raises the question, how high can we go?

![]()

How much would you pay for a cup of coffee? Wikimedia Commons.

When Starbucks announced in late November that it was unveiling a new $7-per-grande-cup brew in select stores, reaction was mixed. Seattle Weekly’s food writer, Hanna Raskin wrote about an office taste test, “The consensus was that the coffee’s good, but not appreciably better than Starbucks’ standard drip.” And yet, the Costa Rica Finca Palmilera Geisha has been doing okay. The Los Angeles Times reported that the online stock sold out in 24 hours, at $40 a bag.

While the news might elicit a Liz-Lemon worthy eye-roll or shooting pangs of jealousy depending on the person, it might actually be something we just have to get used to. Published just a few weeks before Starbucks unrolled its cup of liquid gold, a study from the Royal Botanic Gardens in the U.K. and the Environment Coffee Forest Forum in Ethiopia warned that up to 70 percent of the world’s coffee supply could be gone by 2080 due to climate change.

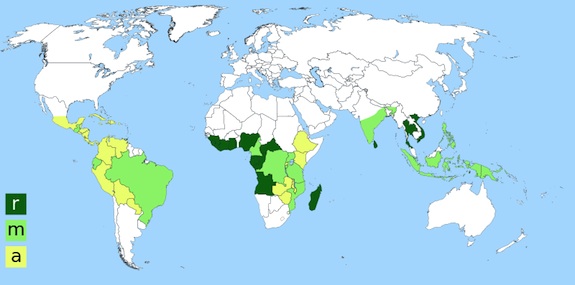

A map of the world’s coffee producing regions. R indicates Coffea robusta, A represents Coffea arabica and M includes both. Wikimedia Commons.

Turns out, the warnings are actually pretty consistent across the board, the World Bank is practically hoarse with all its calls for caution. On November 18, the World Bank released a new study about the effects of climate change over a long period of time, concluding, “The world is barreling down a path to heat up by 4 degrees at the end of the century if the global community fails to act on climate change, triggering a cascade of cataclysmic changes that include extreme heat-waves, declining global food stocks and a sea-level rise affecting hundreds of millions of people.”

New York University associate professor of food studies and economist Carolyn Dimitri says attention to the vulnerability of the world’s food systems is a step in the right direction but not enough. “These are really big and important groups that are talking about this, but how are they going to gain traction given the way our food system has become so industrialized?”

As someone who’s been studying organic food marketing and access since her days at the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Dimitri says she wasn’t too surprised to hear about the $7 coffee. “Living in Manhattan,” she says, “people would probably pay even more than that for a cup of coffee.” She sees the launch as a way to appeal to a new set of customers who might have seen Starbucks as selling adequate but not speciality coffee, whether it be for taste or for its unique ethical sourcing, which Starbucks is seeking to expand.

Though Starbucks aims to have all of its coffee meet standards for farmer wages and working conditions by 2015, Dimitri says, “My students tend to be a little bit suspicious of the big companies that enter this area,” as when Walmart began carrying organic products. But Dimitri has a hard time criticizing large companies motives if the end result is an improved livelihood for farmers. Ethical sourcing practices, as defined by Conservation International, include provisions for environmental sustainability as well as economic.

But the commitment is hard to measure. Taking Starbucks as an example, Dimitri says, “You can do a good thing but really a better thing would be for no one to buy coffee in a coffee shop in a disposable cup. Does ethically sourcing some of your coffee, is that sufficient to outweigh all of the garbage that’s created?”

The impact of climate change is hard to estimate but the study out of Ethiopia took predictions from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change to ask what would happen to Arabica bean crops if the temperature increased within a range of 1.8° C to 4° C.

The potential losses would not only mean more expensive coffee for consumers, but fewer jobs and less economic stability for producers. According to the report, “total coffee sector employment estimated at about 26 million people in 52 producing countries.” The study also reports that coffee is the second most traded commodity after oil.

In another alarm-sounding report from the World Bank, the development agency writes that though global food prices have fallen from a peak in July, “prices remain at high levels – 7 percent higher than a year ago.” Some specific crop prices are much higher still, including maize, which is 17 percent more expensive than it was in October, 2011.

In the case of coffee, Colombia recently announced a plan to offer insurance to growers to protect them from losses incurred from severe weather, according to South Africa’s Times Live.

This World Bank chart maps the current annual rise in sea level due to land-ice melt only, with red being the greatest (around 1.5 mm/year) and blue actually reflecting a drop in sea level. Compare the regions likely to be hardest hit to those that produce the most coffee.

“More people should be thinking about it and talking about it,” says Dimitri. “I don’t think that our policymakers take it as seriously as the researchers do.”

For the consumers who are concerned and have the means and access to purchase sustainably, ethically produced foods, Dimitri says, “they’re willing to make sacrifices in other areas.”

Through a sheer appeal to quality, Starbucks is hoping consumers will find that reason enough to spend on the newest varietal in its Reserve line. Plus, it’s actually not the most expensive cup of coffee ever sold, if you count add-ons. One customer with a veritable blank-check coupon went wild crafting the priciest drink he could, according to Piper Weiss, and topped out at $23.60. His drink–if you can really still call it that–consisted of, “one Java Chip Frappucino ($4.75), plus 16 shots of espresso ($12), a shot of soy milk (.60), a drop of caramel flavoring (.50), a scoop of banana puree ($1), another scoop of strawberry puree (.60), a few vanilla beans(.50), a dash of Matcha powder (.75), some protein powder (.50) and a caramel and mocha drizzle to cap it off (.60).”

Still, for a straight up cup of Joe, it takes the cake. ”It is the highest price we’ve ever had,” a spokesperson told CNBC, adding, “It raises the bar.”

According to the World Bank, EPA, UN and others, that bar doesn’t need much help.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)