The Strange, Giant “Beach Animals” That Are About to Invade America’s Shores

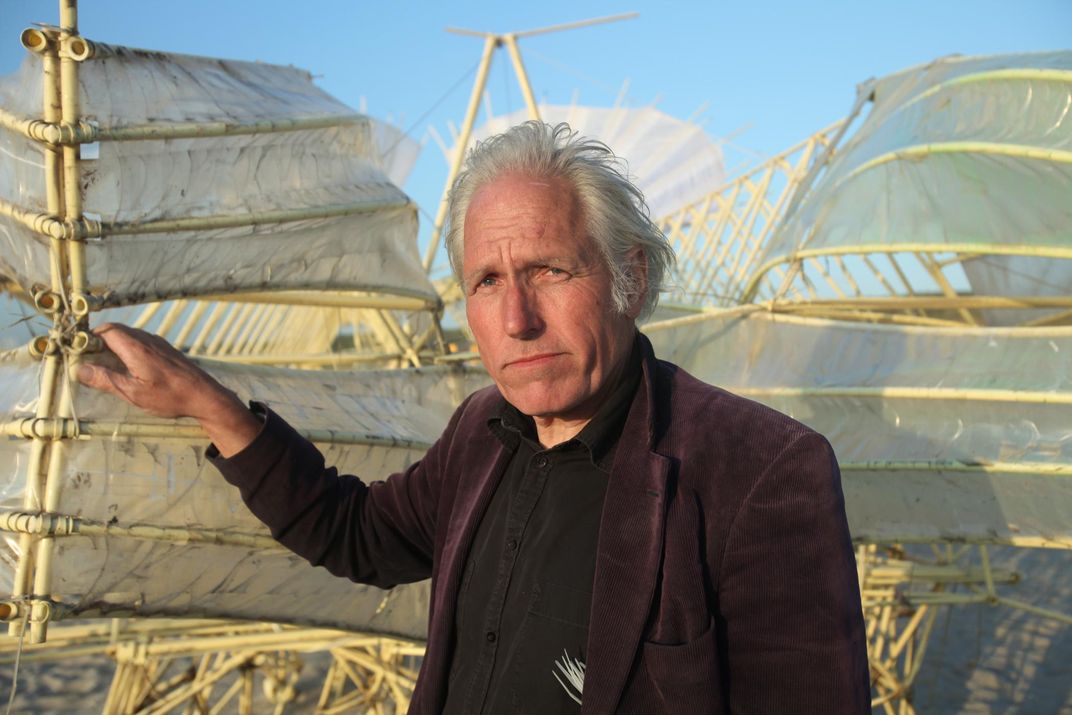

Artist Theo Jansen’s sculptures first became hits on YouTube. Now they’ve reached the shores of New England

The crowd begins to gather more than four miles out, winding its way through wooded suburban neighborhoods, along stone walls and finally across acres of salt marsh. Drivers hunt vainly for parking along narrow country roads, parents schlep beach chairs and piggy-backing toddlers, and cyclists weave merrily in and out of traffic alongside aging hippies, young people whose T-shirts advertise area tech colleges, and a tall man using a large wand to send watermelon-sized soap bubbles over people’s heads. Finally, after crossing over a ridge of grassy sand dunes, the throng spills out onto a beach, joining the thousands of other people who have come to see the famous Strandbeests walk across the sand.

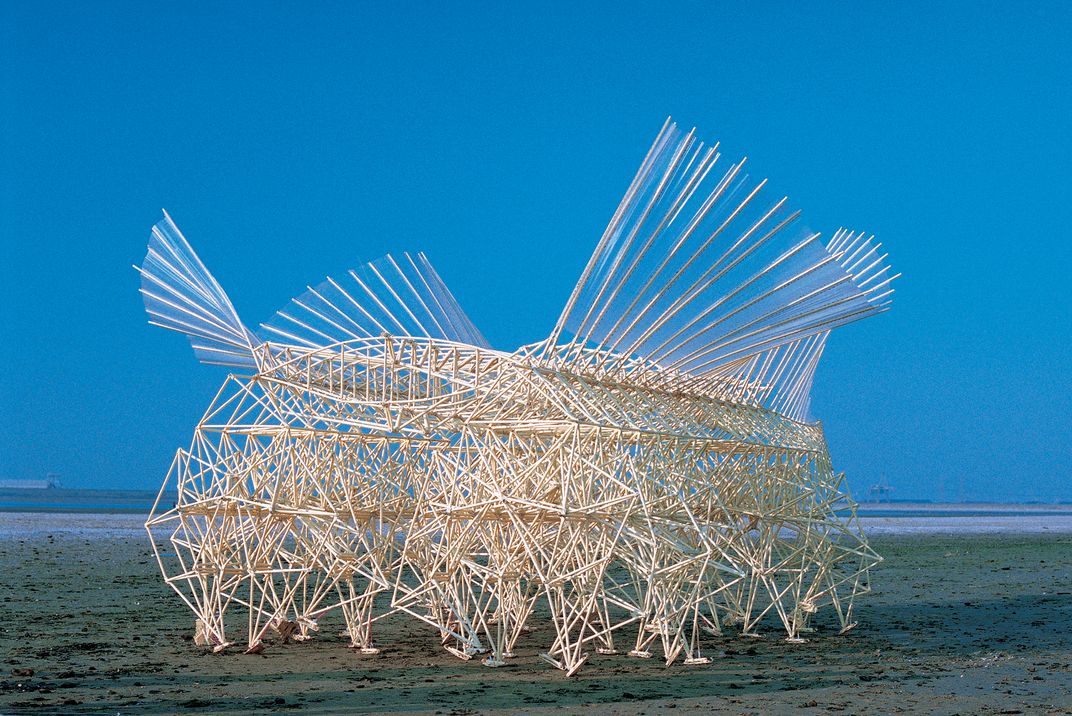

There are two of them, horse-sized contraptions built from ivory-colored PVC tubes, zip ties and clear packing tape. These materials may seem more the materials of a DIY handyman, but to 67-year-old Dutch artist Theo Jansen, they are the building blocks for creating what he calls “a new form of life.” And in the 25 years since Jansen began building his wind-powered “beach animals” near his home in the Netherlands, these kinetic sculptures have won a devoted international following, thanks in large part to hundreds of YouTube videos in which they march across the sand like animated dinosaur skeletons. This fall, the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, will mount Jansen’s first major exhibition in the United States, giving American fans a chance to see the beests up close. Today’s appearance is a preview—one which, astonished museum officials will later report, has drawn more than 10,000 people to Crane Beach, an isolated peninsula an hour north of Boston.

On their preview day, At present, however, the Strandbeests are stuck, hemmed in on all sides by a mass of people standing barefoot in the wet sand. Diesel exhaust fills the air as boats idle offshore, and overhead a prop plane buzzes back and forth, while a camera attached to a quadcopter drone snaps pictures. Then, suddenly, one of the beests springs to life, its plastic sails billowing with a gust of wind, and its handlers, a dozen young men and women in bright yellow shirts, urge the spectators to step back. A cheer rises, the crowd parts, and the beest, looking like a wobbly dragon, lurches forward, taking a few hesitant steps with its pneumatically-powered legs, before it builds up speed as if gaining confidence in itself at last.

“You feel empathy toward it,” notes Trevor Smith, the exhibition’s curator. “The videos embody this dream of perpetual motion, but the beests themselves are temperamental. They require care. There’s a sense of fragility that deepens your appreciation of the creative process, and you see the drive and follow-through required to make a dream a reality.”

The honor of hosting Theo Jansen’s dream is a bit of a coup for the Peabody Essex, which, though one of the largest and oldest museums in the United States, has historically been better-known for its Asian and maritime-related collections than for contemporary art. But in recent years the museum has been expanding both its gallery space and its vision, along the way mounting some truly innovative exhibitions—including, in 2014, a wildly popular installation by French artist Céleste Boursier-Mougenot, in which 70 captive zebra finches were recruited to play electric guitars. That show was also organized by Smith, whose official title is “curator of the present tense.”

“The culture of our time is too important and impacts us in too many ways to reduce it to a genre of ‘contemporary art,’” he explains. “That term still conjures up this idea of exclusivity that is counterproductive, if what we want is to get people to think about the role of creativity in their own lives.” The museum’s “present tense” philosophy may have been what drew Jansen, whose work combines art with old-fashioned tinkering and cutting-edge engineering (he used a computer-programmed genetic algorithm, which mimics natural selection to help design the beests’ legs). Jansen, Smith says, had long hoped to bring the beests to America, “but he wanted to bring them in a way in which people could engage with the complexities of the work,” Smith says.

Complexity may be the key word. Francesca Williams, the museum’s registrar for exhbitions, says hosting the Strandbeests required a “paradigm shift” on the part of staff who are normally tasked with handling art that is a little smaller and a lot less mobile.

The exhibition, which opens September 19, will involve four active beests, including two of the variety Animaris Ordis, eight-foot-long walking units that visitors will be allowed to push and pull; an Animaris Suspendisse, 43 feet long and powered by plastic bottles Jansen calls “wind stomachs,” which will be filled with compressed air, allowing the beest to walk in the gallery; and Animaris Umerus Segundus, a brand new beest designed specifically for this show. (Jansen uses a faux-scientific name for every Strandbeest, and their development is intended to parallel the evolution of flesh-and-blood animals.) Alongside them will be hundreds of “fossils”; Jansen’s sketches, documentation by the photographer Lena Herzog, and interactive elements to help visitors understand the beests’ intricate mechanisms.

The active creatures are the main attraction, and from the perspective of museum staffers they also present the biggest challenge. “It’s as much a performance as an exhibition,” Williams says, “because the end result changes every time.” Unlike most artwork, the beests will need daily repairs and adjustments, and to that end the museum has hired a team of artists with engineering skills (one is a former bicycle mechanic) to work in the gallery. Jansen and the museum have also created a detailed manual that will move with the beests to the show’s next stops, at the Chicago Cultural Center and San Francisco’s Exploratorium, after the Peabody Essex show closes on January 3.

Jansen has said that he hopes the Strandbeests will one day become self-sufficient and outlive their creator. “He’s thinking about the survival of his species,” says Williams. In that spirit, the Peabody Essex is promoting another art-world unorthodoxy: reproduction. During an opening weekend festival, guest artists and engineers will help museum-goers craft their own beests, while more technical types will gather for an all-night hack-a-thon, in which teams compete to solve a “Strandbeest challenge.” The museum will also display “hack beests” inspired by Jansen’s work, including one powered by a hamster and another made of Legos.

If previews are any guide, the Peabody Essex will have another blockbuster exhibition on its hands: Strandbeest fans are everywhere, and their passion for these strange, hapless yet elegant creatures rivals that of any rock and roll groupie.

“It’s a different form of life!” enthuses Ayfer Ali, an economics professor from Spain, who has been following the Strandbeests online for three years. She extended her Boston vacation to make the trek up to Crane Beach, and she is thrilled when Smith mentions that the beests will take part in an exhibition in Madrid in October.

“There’s something magic about the idea that someone can take these inanimate materials and turn them into something you can’t take your eyes off,” Smith says, as the Strandbeests’ handlers remove their sails and lead them, like livestock at the end of a long day of grazing, back up the beach to the trucks waiting to return them to the museum. “We’ve known how to make things move for millennia, but to make something move that is that simple… That one man has been able to do that is very powerful. It shows how important it is to have and pursue a dream.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/amy.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/amy.png)