The Architecture of Superman: A Brief History of The Daily Planet

The real-world buildings that may have inspired Superman’s iconic office tower workplace

![]()

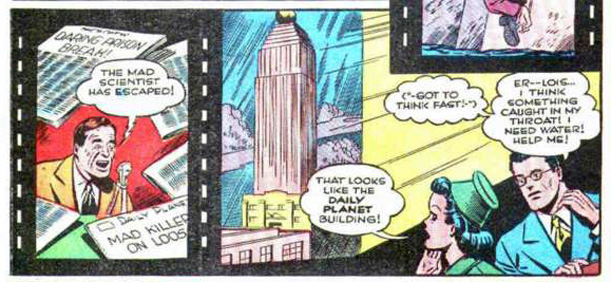

The first appearance of the iconic Daily Planet building in the “The Arctic Giant,” the fourth episode of the Superman cartoon created by Fleischer Studios. Original airdate: February 26, 1942

“Look! Up in the Sky!”

“It’s a bird!”

“It’s a plane!”

“It’s a giant metal globe hurtling toward us that will surely result in our demise! Oh, nevermind…Superman took care of it.”

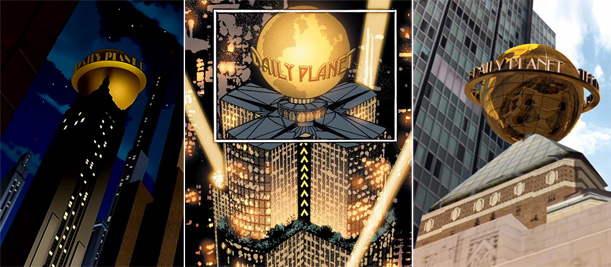

Whenever disaster strikes Superman’s Metropolis, it seems that the first building damaged in the comic book city is the Daily Planet – home to mild-mannered reporter Clark Kent, his best buddy Jimmy Olsen, and his gal pal and sometimes rival Lois Lane. The enormous globe atop the Daily Planet building is unmistakable on the Metropolis skyline and might as well be a bulls-eye for super villains bent on destroying the city. But pedestrians know that when it falls –and inevitably, it falls– Superman will swoop in at the last minute and save them all (The globe, however, isn’t always so lucky. The sculpture budget for that building must be absolutely astronomical).

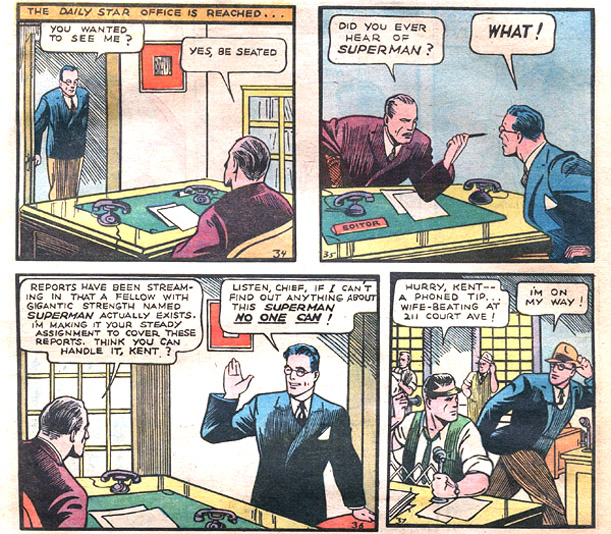

Though well known today, the Daily Planet building wasn’t always so critical to the Superman mythos. In fact, when the Man of Steel made his 1938 debut in the page of Action Comics #1, it didn’t exist at all. Back then, Clark Kent worked for the The Daily Star, in a building of no particular architectural significance because, well, there was no significant architecture in those early comics. The buildings were all drawn as basic, generic backdrops with little distinguishing features that did little more than indicate some abstract idea of “city”.

Clark Kent working at The Daily Star in Action Comics #1. Rest assured, Superman puts a stop to the wife-beating mentioned in the final panel. (image: Art by Joe Shuster, via Comic Book Resources)

As noted by Brian Cronin, author of Was Superman a Spy? and the blog Comic Book Legends Revealed, Kent’s byline didn’t officially appear under the masthead of a paper called The Daily Planet until the 1940 Superman radio show, which, due to the nature of the medium, obviously couldn’t go into great detail about the building. That same year, The Daily Star became The Daily Planet.

But the lack of any identifiable architecture in these early representations of the Planet hasn’t stopped readers from speculating on the architectural origin of the most famous fictitious edifices in funnybooks. Unsurprisingly, Cleveland lays claim to the original Daily Planet. But so too does Toronto. And a strong case can be made for New York. So what was the true inspiration behind the iconic Daily Planet building?

The old Toronto Star Building, designed by Chapman and Oxley, completed in 1929 and demolished in 1972. (image: wikipedia)

Although Superman was famously created in Cleveland, Superman co-creator and original artist Joe Shuster was less famously created in Toronto, where, as a young newsboy, he sold the city’s paper of record, The Toronto Daily Star. In the last interview Shuster ever gave, he told the paper, now renamed The Toronto Star, about the city’s influence on his early Superman designs: “I still remember drawing one of the earliest panels that showed the newspaper building. We needed a name, and I spontaneously remembered The Toronto Star. So that’s the way I lettered it. I decided to do it that way on the spur of the moment, because The Star was such a great influence on my life.” But did the actual Star building directly influence the design of the Daily Planet? Shuster doesn’t say, but it doesn’t seem too likely. The Art Deco building, designed by Canadian architects Chapman and Oxley, wasn’t completed until 1929 – about five years after Shuster left Toronto for Cleveland, Ohio.

Incidentally, this wasn’t the only time that Chapman and Oxley almost had their work immortalized in fiction. The firm also designed the Royal Ontario Museum, which was expanded in 2007 with a radical addition designed by Daniel Libeskind that appeared in the pilot episode of the television series “Fringe.” But I digress.

The AT&T Huron Road Building in Cleveland, Ohio, designed by Hubbell and Benes and completed in 1927 (image: wikipedia)

In Cleveland, Superman fans claim that the Daily Planet was inspired by the AT&T Huron Road Building (originally the Ohio Bell Building), another Art Deco design, built by Cleveland architects Hubbell & Benes in 1927. Coincidentally, the building is currently topped with a globe, the AT&T logo – perhaps the owners want to reinforce the notion that this is the true Daily Planet Building. After all, harboring the world’s greatest superhero has to be good for property value, right? It’s not certain how this rumor got started, but Shuster has denied that anything in Cleveland influenced his designs for Metropolis.

Obviously, the massive sculptural globe is the one thing missing from the above buildings. And really, it’s the only thing that matters. The globe is the feature that identifies the building as the site of Superman’s day job and, more often than not, the collateral damage resulting from his other day job.

Surprisingly, the globe didn’t make its first appearance in the comics, but in the iconic Fleischer Studios Superman Cartoon (see top image). Specifically, the fourth episode of the series, ”The Arctic Giant,” which first aired in 1942. It must’ve made an impression on the Superman artist because that same year, an early version of the globe-peaked Daily Planet building made its comic book debut in Superman #19.

A panel from Superman #19 featuring the first comic book apeparance of the Daily Planet globe (image: Comic Book Resources)

Whereas the previous iterations of the Daily Planet building were little more than architectural abstractions loosely influenced by Art Deco architecture, the animated Daily Planet building may have been inspired by the former headquarters for Paramount Pictures in Manhattan, completed in 1927 by Rapp & Rapp, a prominent Chicago architecture firm known for building many beautiful theaters across the country.

The Paramount Building in New York, designed by Rapp & Rapp and completed in 1927 (image: wikipedia)

Located at 1501 Broadway, the Paramount Building is just a 5 minute walk away from the original location of Fleischer Studios at 1600 Broadway. Although today it is dwarfed by the modern high-rises of Midtown Manhattan, in the 1940s, the 33-story building still towered over many of its neighbors. It seems reasonable to assume that the pyramidal tower, with its step-backs dictated by NYC building codes, its four enormous clocks, and, of course, the glass globe at its peak, may have inspired Fleischer artists designing the animated architecture of the cartoon Metropolis.

Over the 75 years since Superman was introduced to the world, the Daily Planet building has been drawn many different ways by many, many different artists. But the globe is consistent. The globe defines the Daily Planet building. But, more generally, so too does Art Deco. Indeed, the entire city of Metropolis is often drawn as an Art Deco city.

The term “Art Deco” is a derived from the 1925 Expositions Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, a world exhibition held in Paris that extolled the virtues of Modern design and promoted a complete break from historical styles and traditions. Unlike the stripped-down austere buildings that came to define International Style Modernism, Art Deco architecture doesn’t eschew ornament. Instead, it combines traditional ideas of craft and decoration with streamlined machine age stylistics. Its geometric ornament is derived not from nature but from mechanization. The buildings are celebrations of the technological advancements that made skyscrapers possible in the first place. In the 1920s and 1930s, Art Deco was optimistic, it was progressive, it represented the best in mankind at the time – all qualities shared by Superman. Like the the imposing neo-Gothic spires and grotesque gargoyles of Gotham City that influence Batman’s darker brand of heroics, Metropolis is a reflection of its hero. And even though Superman may be from another galaxy, The Daily Planet is the center of his world.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)