The Measure of Genius: Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel at 500

Half a millennium later, the story of the painting of the Sistine Chapel is as fascinating as Michelangelo’s masterpiece itself

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/The-Creation-of-Adam-Michelangelo-631.jpg)

In the spring of 1509, just two years after a mapmaker coined the word “America” in honor of the explorer Amerigo Vespucci, a fellow Florentine named Buonarotti was beginning to work on one of the defining masterpieces of Western Civilization. His first name—Michelangelo—would also reverberate through the ages. And, like many of the early transatlantic voyages of discovery, his ceiling frescoes in Rome’s Sistine Chapel had gotten off to a terrible start.

“He was working on the largest multi-figure compositions of the entire ceiling when the actual fresco plaster itself became infected by a kind of lime mold, which is like a great bloom of fungus,” says Andrew Graham-Dixon, chief art critic for London’s Sunday Telegraph. “So he had to chip the whole thing back to zero and start again. Eventually he sped up. He got better.”

However difficult the conditions—and even the challenge of painting at a height of 65 feet required considerable ingenuity, with scaffolds and platforms slotted into specially fashioned wall openings—by the time Michelangelo unveiled the work in 1512, he had succeeded in creating a transcendent work of genius, one which continues to inspire millions of pilgrims and tourists in Vatican City each year. The Sistine Chapel holds a central place in Christendom as the private chapel of the pope and the site of the papal enclave, where the College of Cardinals gathers to elect new popes. Thanks to Michelangelo, however, the chapel’s significance extends to all who have been inspired by the originality and power of his vision—both directly and indirectly, through its influence on subsequent artists and the iconography of world culture.

Graham-Dixon immersed himself in the paintings for some time and has now written a book for general readers, Michelangelo and the Sistine Chapel (Skyhorse Publishing), published to coincide with the work’s 500th anniversary. As he plumbed the details, he found more and more to admire and ponder.

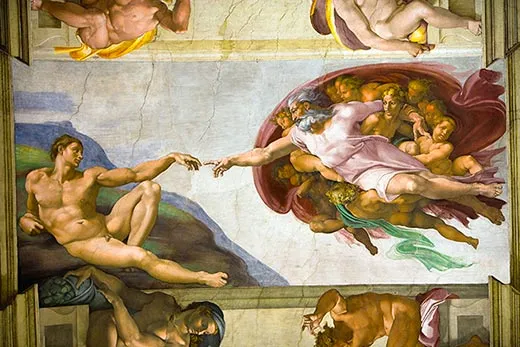

Take The Creation of Adam, with its portrayal of God’s finger reaching to touch Adam’s —undoubtedly the most famous detail of all. It has been endlessly reproduced and copied; think, for instance, of the well-known poster for the movie E.T.

“Yet I found myself wondering, why did Michelangelo have God create Adam with a finger?” Graham-Dixon says. “In other representations, for example, if you look at Ghiberti’s doors in Florence, God raises up Adam with a gesture of his hand. And as I turned over various ideas and theories, I began to see it as the creation of the education of Adam, because that’s the symbolism of the finger. God writes on us with his finger, in certain traditions of theology. In the Jewish tradition, that’s how he writes the tablets of the Ten Commandments for Moses—he sort of lasers them with his finger. The finger is the conduit through which God’s intelligence, his ideas and his morality seep into Man. And if you look at that painting very closely, you see that God isn’t actually looking at Adam, he’s looking at his own finger, as if to channel his own instructions and thoughts through that finger.”

Graham-Dixon’s book takes up several controversies and myths surrounding the Sistine Chapel, such as the notion that Michelangelo painted the vault of the chapel lying down on his back; this is how he was portrayed, for instance, in the 1965 Hollywood film The Agony and the Ecstasy, based on Irving Stone’s historical novel. In fact, Michelangelo painted standing up, Graham-Dixon says, but was forced to crane his neck at a horrible angle for nearly four years, causing him painful spasms, cramps and headaches. “My beard toward Heaven, I feel the back of my brain upon my neck,” he wrote in a comical poem for a friend. “My loins have penetrated to my paunch…I’m not in a good place, and I’m no painter.”

He meant that literally. The 34-year-old Michelangelo was renowned for such statues as David and the Pietà, and he regarded his Sistine Chapel commission from Pope Julius II with the utmost suspicion. In fact he believed that enemies and rivals had concocted the idea in order to see him fail on a grand scale. “Michelangelo felt that God chose him to be a sculptor,” says Graham-Dixon, “so to be asked to paint—he didn’t consider that as serious a vocation. What he’d wanted to do, what he’d spent years of his life preparing to do, had spent eight months in the mountains of Carrara with two men and a donkey getting ready to do, was to create this great monumental tomb for Julius II.” A much smaller tomb was completed many years later.

For five centuries, people have spoken of Michelangelo’s masterworks as if they were a superhuman achievement. Yet the modern, democratic temperament reflexively seeks out the human side of heroes and celebrities, to experience their struggles and fallibility at close hand. Graham-Dixon suggests that this hankering for kinship and connection is not likely to be satisfied by the paintings of the Sistine Chapel.

“I have to say it is kind of superhuman,” he says. “I find the Sistine Chapel quite a daunting work of art. It’s not very accommodating to human beings, in many ways. It presents the image of God as a dream to which we aspire. It describes the dream of oneness with God as one from which we’ve all been expelled, and we can only get back to it with a great deal of prayer and hard work. There’s a sense, as well, I think—it’s only a sort of feeling I have, I can’t really justify it—but I have the feeling that Michelangelo felt he was far, far above the multitude of ordinary people. And not just physically, up on his platform, but morally as well. There is, of course, a humanity in it, but it’s a very, very hard one, and it can’t easily be turned into a nice picture.”

Not a nice picture, perhaps, but certainly one that inspires awe, in the truest sense.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jamie-Katz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jamie-Katz-240.jpg)