The Saddest Movie in the World

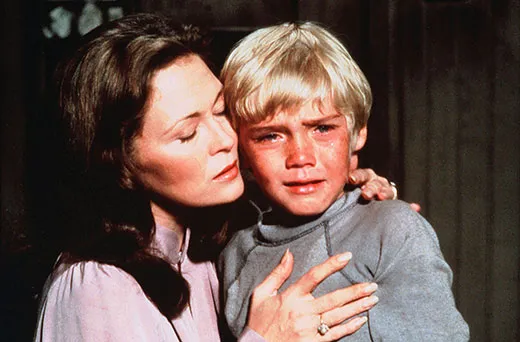

How do you make someone cry for the sake of science? The answer lies in a young Ricky Schroder

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/saddest-movie-The-Champ-Ricky-Schroder-631.jpg)

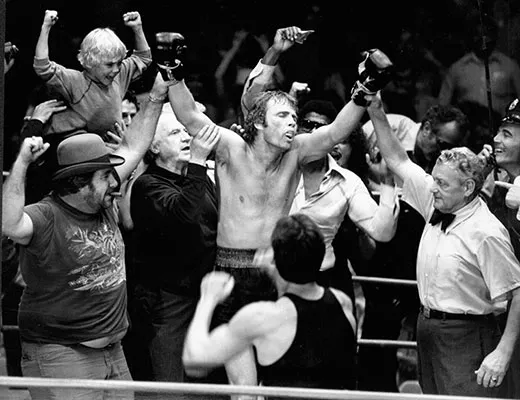

In 1979, director Franco Zeffirelli remade a 1931 Oscar-winning film called The Champ, about a washed-up boxer trying to mount a comeback in the ring. Zeffirelli’s version got tepid reviews. The Rotten Tomatoes website gives it only a 38 percent approval rating. But The Champ did succeed in launching the acting career of 9-year-old Ricky Schroder, who was cast as the son of the boxer. At the movie’s climax, the boxer, played by Jon Voight, dies in front of his young son. “Champ, wake up!” sobs an inconsolable T.J., played by Schroder. The performance would win him a Golden Globe Award.

It would also make a lasting contribution to science. The final scene of The Champ has become a must-see in psychology laboratories around the world when scientists want to make people sad.

The Champ has been used in experiments to see if depressed people are more likely to cry than non-depressed people (they aren’t). It has helped determine whether people are more likely to spend money when they are sad (they are) and whether older people are more sensitive to grief than younger people (older people did report more sadness when they watched the scene). Dutch scientists used the scene when they studied the effect of sadness on people with binge eating disorders (sadness didn’t increase eating).

The story of how a mediocre movie became a good tool for scientists dates back to 1988, when Robert Levenson, a psychology professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and his graduate student, James Gross, started soliciting movie recommendations from colleagues, film critics, video store employees and movie buffs. They were trying to identify short film clips that could reliably elicit a strong emotional response in laboratory settings.

It was a harder job than the researchers expected. Instead of months, the project ended up taking years. “Everybody thinks it’s easy,” Levenson says.

Levenson and Gross, now a professor at Stanford, ended up evaluating more than 250 films and film clips. They edited the best ones into segments a few minutes long and selected 78 contenders. They screened selections of clips before groups of undergraduates, eventually surveying nearly 500 viewers on their emotional responses to what they saw on-screen.

Some film scenes were rejected because they elicited a mixture of emotions, maybe anger and sadness from a scene depicting an act of injustice, or disgust and amusement from a bathroom comedy gag. The psychologists wanted to be able to produce one predominant, intense emotion at a time. They knew that if they could do it, creating a list of films proven to generate discrete emotions in a laboratory setting would be enormously useful.

Scientists testing emotions in research subjects have resorted to a variety of techniques, including playing emotional music, exposing volunteers to hydrogen sulfide (“fart spray”) to generate disgust or asking subjects to read a series of depressing statements like “I have too many bad things in my life” or “I want to go to sleep and never wake up.” They’ve rewarded test subjects with money or cookies to study happiness or made them perform tedious and frustrating tasks to study anger.

“In the old days, we used to be able to induce fear by giving people electric shocks,” Levenson says.

Ethical concerns now put more constraints on how scientists can elicit negative emotions. Sadness is especially difficult. How do you induce a feeling of loss or failure in the laboratory without resorting to deception or making a test subject feel miserable?

“You can’t tell them something horrible has happened to their family, or tell them they have some terrible disease,” says William Frey II, a University of Minnesota neuroscientist who has studied the composition of tears.

But as Gross says, “films have this really unusual status.” People willingly pay money to see tearjerkers—and walk out of the theater with no apparent ill effect. As a result, “there’s an ethical exemption” to making someone emotional with a film, Gross says.

In 1995, Gross and Levenson published the results of their test screenings. They came up with a list of 16 short film clips able to elicit a single emotion, such as anger, fear or surprise. Their recommendation for inducing disgust was a short film showing an amputation. Their top-rated film clip for amusement was the fake orgasm scene from When Harry Met Sally. And then there’s the two-minute, 51-second clip of Schroder weeping over his father’s dead body in The Champ, which Levenson and Gross found produced more sadness in laboratory subjects than the death of Bambi’s mom.

“I still feel sad when I see that boy crying his heart out,” Gross says.

“It’s wonderful for our purposes,” Levenson says. “The theme of irrevocable loss, it’s all compressed into that two or three minutes.”

Researchers are using the tool to study not just what sadness is, but how it makes us behave. Do we cry more, do we eat more, do we smoke more, do we spend more when we’re sad? Since Gross and Levenson gave The Champ two thumbs-up as the saddest movie scene they could find, their research has been cited in more than 300 scientific articles. The movie has been used to test the ability of computers to recognize emotions by analyzing people’s heart rate, temperature and other physiological measures. It has helped show that depressed smokers take more puffs when they are sad.

In a recent study, neuroscientist Noam Sobel at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel showed the film clip to women to collect tears for a study to test the sexual arousal of men exposed to weepy women. They found that when men sniffed tear-filled vials or tear-soaked cotton pads, their testosterone levels fell, they were less likely to rate pictures of women’s faces as attractive, and the part of their brains that normally light up in MRI scans during sexual arousal were less active.

Other researchers kept test subjects up all night and then showed them clips from The Champ and When Harry Met Sally. Sleep deprivation made people look about as expressive, the team found, as a zombie.

“I found it very sad. I find most people do,” says Jared Minkel of Duke University, who ran the sleep-deprivation study. “The Champ seems to be very effective in eliciting fairly pure feeling states of sadness and associated cognitive and behavioral changes.”

Other films have been used to produce sadness in the lab. When he needed to collect tears from test subjects in the early 1980s, Frey says he relied on a film called All Mine to Give, about a pioneer family in which the father and mother die and the children are divided up and sent to the homes of strangers.

“Just the sound of the music and I would start crying,” Frey says.

But Levenson says he believes the list of films he developed with Gross is the most widely used by emotion researchers. And of the 16 movies clips they identified, The Champ may be the one that has been used the most by researchers.

“I think sadness is a particularly attractive emotion for people to try to understand,” Gross says.

Richard Chin is a journalist from St. Paul, Minnesota.

The 16 Short Film Clips and the Emotions They Evoked:

Amusement: When Harry Met Sally and Robin Williams Live

Anger: My Bodyguard and Cry Freedom

Contentment: Footage of waves and a beach scene

Disgust: Pink Flamingos and an amputation scene

Fear: The Shining and Silence of the Lambs

Neutral: Abstract shapes and color bars

Sadness: The Champ and Bambi

Surprise: Capricorn One and Sea of Love

Source: Emotion Elicitation Using Films [PDF], by James J. Gross and Robert W. Levenson in Congition and Emotion (1995)