The Surprising Satisfactions of a Home Funeral

When his father and father-in-law died within days of each other, author Max Alexander learned much about the funeral industry

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Bob-Baldwin-Jim-Alexander-631.jpg)

Two funerals, two days apart, two grandfathers of my two sons. When my father and father-in-law died in the space of 17 days in late 2007, there wasn't a lot of time to ruminate on the meaning of it all. My wife, Sarah, and I were pretty busy booking churches, consulting priests, filing newspaper notices, writing eulogies, hiring musicians, arranging military honor guards and sorting reams of paperwork (bureaucracy outlives us all), to say nothing of having to wrangle last-minute plane tickets a week before Christmas. But all that was a sideshow. Mostly we had to deal with a couple of cold bodies.

In life both men had been devout Catholics, but one was a politically conservative advertising man, the other a left-wing journalist; you'll have to trust me that they liked each other. One was buried, one was cremated. One was embalmed, one wasn't. One had a typical American funeral-home cotillion; one was laid out at home in a homemade coffin. I could tell you that sorting out the details of these two dead fathers taught me a lot about life, which is true. But what I really want to share is that dead bodies are perfectly OK to be around, for a while.

I suppose people whose loved ones are missing in action or lost at sea might envy the rest of us, for whom death typically leaves a corpse, or in the polite language of funeral directors, "the remains." Yet for all our desire to possess this tangible evidence of a life once lived, we've become oddly squeamish about our dead. We pay an average of $6,500 for a funeral, not including cemetery costs, in part so we don't have to deal with the physical reality of death. That's 13 percent of the median American family's annual income.

Most people in the world don't spend 13 percent of anything on dead bodies, even once in a while. How we Westerners have arrived at this state is a long story—you can start with the Civil War, which is when modern embalming was developed—but the story is changing.

A movement toward home after-death care has convinced thousands of Americans to deal with their own dead. A nonprofit organization called Crossings (www.crossings.net) maintains that besides saving lots of money, home after-death care is greener than traditional burials—bodies pumped full of carcinogenic chemicals, laid in metal coffins in concrete vaults under chemically fertilized lawns—which mock the biblical concept of "dust to dust." Cremating an unembalmed body (or burying it in real dirt) would seem obviously less costly and more eco-friendly. But more significant, according to advocates, home after-death care is also more meaningful for the living.

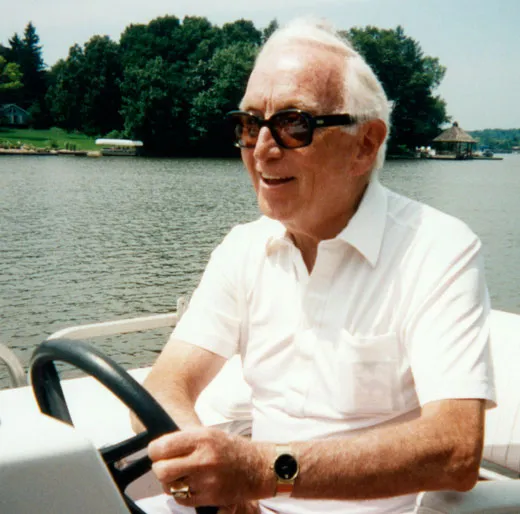

I wasn't sure exactly why that would be, but Sarah, her sisters and their mother were intrigued. Bob, her dad (he was the left-wing journalist), had brain cancer and was nearing the end. In hospice care at his home in Maine near our own, he wasn't able to participate in the conversations about his funeral, but earlier he had made it clear that he didn't want a lot of money spent on it.

Sarah hooked up with a local support group for home after-death care. We watched a documentary film called A Family Undertaking, which profiles several home funerals around the country. I was especially moved by the South Dakota ranch family preparing for the death of their 90-year-old patriarch, probably because they did not fit my preconception of home-funeral devotees as granola-crunching Berkeley grads.

So a few weeks before Bob died, my 15-year-old son, Harper, and I made a coffin out of plywood and deck screws from Home Depot. I know that sounds cheesy, but it was nice hardwood veneer, and we applied a veneer edging for a finished look. I could have followed any number of plans from the Internet, but in the end I decided to wing it with my own design. We routed rabbet joints for a tight construction.

"I guess we wouldn't want him falling out the bottom," Harper said.

"That would reflect poorly on our carpentry skills," I agreed.

We rubbed linseed oil into the wood for a deep burnish, then, as a final touch, made a cross of cherry for the lid. Total cost: $90.98.

Sarah learned that Maine does not require embalming—a recognition that under normal circumstances human remains do not pose a public health risk (nor do they deteriorate visibly) for a few days after death.

When Bob died, on a cold evening in late November, Sarah, her sister Holly and I gently washed his body with warm water and lavender oil as it lay on the portable hospital bed in the living room. (Anointing a body with aromatic oils, which moisten the skin and provide a calming atmosphere for the living, is an ancient tradition.) I had been to plenty of funerals and seen many a body in the casket, but this was the first time I was expected to handle one. I wasn't eager to do so, but after a few minutes it seemed like second nature. His skin remained warm for a long time—maybe an hour—then gradually cooled and turned pale as the blood settled. While Holly and I washed his feet, Sarah trimmed his fingernails. (No, they don't keep growing after death, but they were too long.) We had to tie his jaw shut with a bandanna for several hours until rigor mortis set in, so his mouth would not be frozen open; the bandanna made him look like he had a toothache.

We worked quietly and deliberately, partly because it was all new to us but mainly out of a deep sense of purpose. Our work offered the chance to reflect on the fact that he was really gone. It wasn't Bob, just his body.

Bob's widow, Annabelle, a stoic New Englander, stayed in the kitchen during most of these preparations, but at some point she came in and held his hands. Soon she was comfortable lifting his arms and marveling at the soft stillness of her husband's flesh. "Forty-four years with this man," she said quietly.

Later that night, with the help of a neighbor, we wrestled the coffin into the living room, filled it with cedar chips from the pet store and added several freezer packs to keep things cool. Then we lined it with a blanket and lay Bob inside. Movies always show bodies getting casually lifted like a 50-pound sack of grain; in real life (or death?), it strained four of us to move him.

The next night we held a vigil. Dozens of friends and family trailed through the living room to view Bob, surrounded by candles and flowers. He looked unquestionably dead, but he looked beautiful. Harper and I received many compliments on our coffin. Later, when the wine flowed and the kitchen rang with laughter and Bob was alone again, I went in to see him. I held his cool hands and remembered how, not so long ago, those hands were tying fishing lures, strumming a banjo, splitting wood. Those days were over, and that made me sad, but it also felt OK.

We did have to engage a few experts. Although Maine allows backyard burials (subject to local zoning), Bob had requested cremation. A crematorium two hours away was sympathetic to home after-death care. The director offered to do the job for just $350, provided we delivered the body.

That entailed a daylong paper chase. The state of Maine frowns on citizens driving dead bodies around willy-nilly, so a Permit for Disposition of Human Remains is required. To get that, you need a death certificate signed by the medical examiner or, in Bob's case in a small town, the last doctor to treat him. Death certificates, in theory at least, are issued by the government and available at any town office. But when Sarah called the clerk she was told, "You get that from the funeral home."

"There is no funeral home," she replied.

"There's always a funeral home," said the clerk.

Sarah drove to the town office, and after a lot of searching, the clerk turned up an outdated form. The clerk at the next town over eventually found the proper one. Then Sarah had to track down her family doctor to sign it. We had a firm appointment at the crematorium (burning takes up to five hours, we learned), and time was running out. But finally we managed to satisfy the bureaucracy and load Bob's coffin into the back of my pickup truck for an on-time delivery. His ashes, in an urn made by an artist friend, were still warm as Sarah wrote the check. We planned to scatter them over the Atlantic later.

Then my dad died—suddenly, a thousand miles away, in Michigan. He lived alone, far from his three sons, who are spread from coast to coast. Home after-death care was out of the question; even if logistics had allowed it, my father had planned his funeral down to the clothes he would wear in his coffin and the music to be played at the service (Frank Sinatra's "I'll Be Seeing You"). We sat down with the funeral-home director (a nice man, also chosen by my dad) in a conference room where Kleenex boxes were strategically positioned every few feet, and went over the list of services ($4,295 in Dad's case) and merchandise. We picked a powder-coated metal coffin that we thought Dad would have liked; happily, it was also priced at the lower end of the range ($2,595). He had already received a plot free from the town. The total cost was $11,287.83, including cemetery charges and various church fees.

I was sad that I hadn't arrived in Michigan to see him before he died; we never said goodbye. "I'd like to see my father," I told the funeral director.

"Oh, you don't want to see him now," he replied. "He hasn't been embalmed."

"Actually, that's precisely why I'd like to see him."

He cleared his throat. "You know there was an autopsy." My father's death, technically due to cardiac arrest, had happened so quickly that the hospital wanted to understand why. "A full cranial autopsy," he added.

Well, he had me there. I relented. Then I told him the story of Sarah's father—the homemade coffin, the bandanna around the jaw—and his own jaw dropped lower and lower.

"That would be illegal in Michigan," he said.

In fact, do-it-yourself burials without embalming are possible in Michigan as long as a licensed funeral director supervises the process. I don't think he was lying, just misinformed.

The next day I got to see my dad, embalmed and made up, with rosy cheeks and bright red lips. Clearly an attempt had been made to replicate his appearance in life, but he looked more like a wax museum figure. I touched his face, and it was as hard as a candle. Sarah and I exchanged knowing glances. Later she said to me, "Why do we try to make dead people look alive?"

On a frigid December day, we lowered Dad's coffin into the ground—or, more accurately, into a concrete vault ($895) set in the ground. It is not easy for me to say this, but here I must report with embarrassment that in life my father had his own personal logo—a stylized line drawing of his face and his trademark oversize spectacles. It appeared on his stationery, his monogrammed windbreakers, even a flag. In accord with his wishes, the logo was engraved on his tombstone. Beneath were the words "I'll Be Seeing You."

It was different, the funeral director acknowledged, yet not as different as my father-in-law's passage. Home after-death care is not for everyone or every situation, but there is a middle ground. Before my dad's church service, the funeral director confided to me that he was exhausted: "I got a call at midnight to pick up a body in Holland," a town 30 miles away. That night had brought a major snowstorm.

"You drove through that storm in the middle of the night to get a body?" I asked.

He shrugged, explaining that more people these days are dying at home, and when they die, the family wants the body removed immediately. "Usually they call 911," he said.

It occurred to me that if more Americans spent more time with their dead—at least until the next morning—they would come away with a new respect for life, and possibly a larger view of the world. After Pakistan's Benazir Bhutto was assassinated, I saw a clip of her funeral. They had put her in a simple wooden coffin. "Hey," I said to my son, "we could have built that."

Max Alexander used to edit for Variety and People. He is writing a book about Africa.