These Artistic Interpretations of the Star-Spangled Banner Call Out the Inner Patriot

In paintings, photos, music, videos and poetry, contemporary artists intrepret the flag that bravely waved above Fort McHenry

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/61/b5/61b57bf2-d35c-46a6-baad-a560eaf92c8d/jun14_i12_starspangledbanner.jpg)

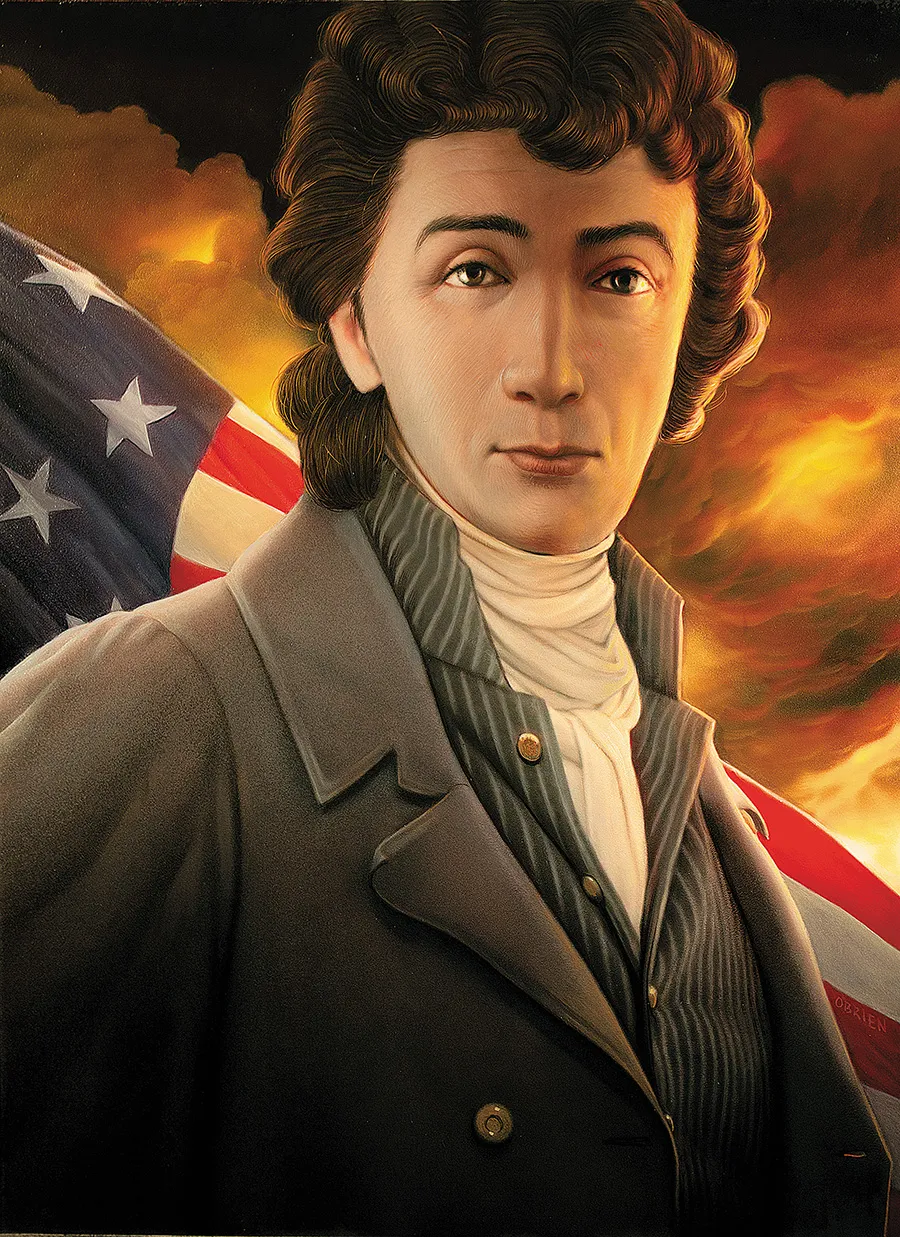

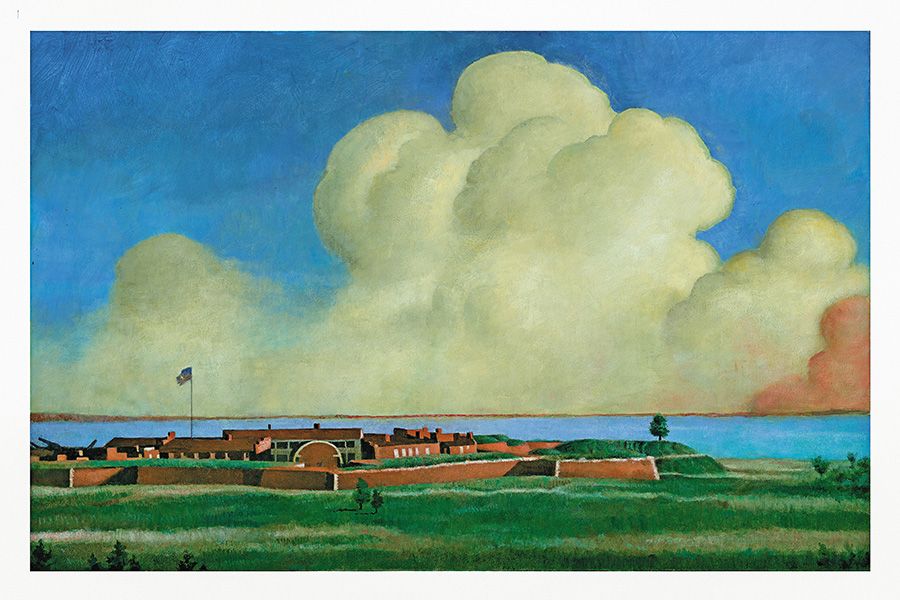

As national treasures go, it was a bargain: $405.90, paid to Mary Pickersgill of Baltimore, who fashioned it from red, blue and undyed wool, plus cotton for the 15 stars, to fly at the fortress guarding the city’s harbor. An enormous flag, 30 by 42 feet, it was intended as a bold statement to the British warships that were certain to come. And when, in September 1814, the young United States turned back the invaders in a spectacular battle witnessed by Francis Scott Key, he put his joy into a verse published first as “Defence of Fort M’Henry” and then, set to the tune of a British drinking song, immortalized as “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

The flag itself, enshrined since 2008 in a special chamber at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History following a $7 million restoration—and due to be celebrated June 14 with a nationwide singalong (anthemforamerica.si.edu)—remains a bold statement. But what is it saying now, 200 years later? We asked leading painters, musicians, poets and other artists to consider that question. You might be inspired by their responses, or provoked. But their artworks give proof that the anthem and the icon are as powerful as ever, symbols of an ever-expanding diversity of ideas about what it means to be an American.

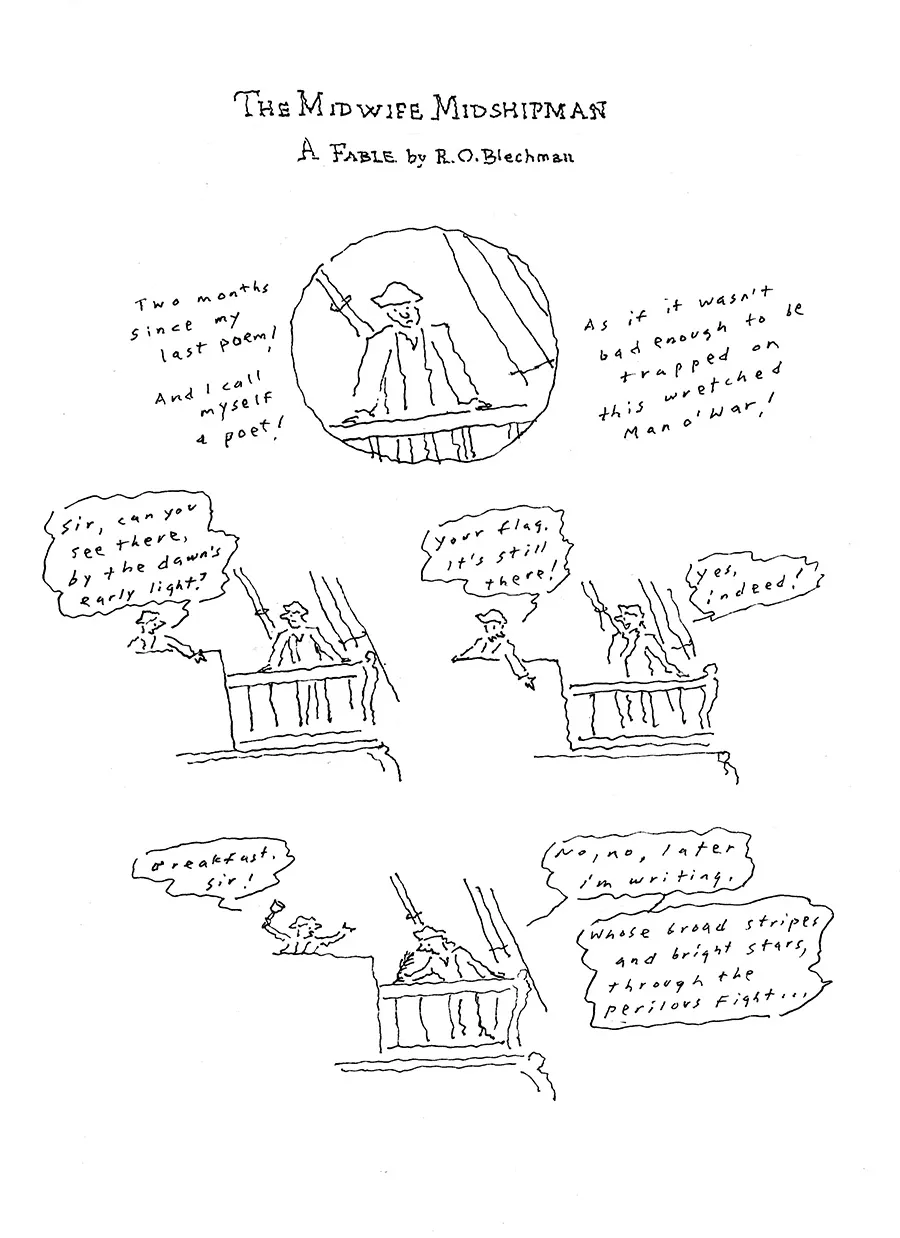

Broad Stripes and Bright Stars by George Green

Composing this poem, Green recalled seeing Jimi Hendrix perform the national anthem in 1969 and watching the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks from a New York rooftop.

It was a joyful noise unto the Lord

that Hendrix made that morning, smelting down

the national anthem. He did a Motown saraband

and roused the bleary throng of lotus-eaters

so gallantly streaming there in the Woodstock pasture.

The gang at the V.F.W. was not amused,

preferring a traditional arrangement

of the peppy trumpet march turned drinking song

first known as “To Anacreon in Heaven.”

Enter Francis Scott Key, the lawyer-poet,

perched in the rigging of a British sloop,

an overdressed envoy gesticulating

like a tenor toward the bombed fort and snapping flag,

his verses coming in a vatic trance

to be scribbled later on an envelope.

All night on deck Doc Beane had paced and nattered,

“Is our flag still there?” It was, and Key’s poetastery

was soon sung out by choirs across the land.

But the president and his bewildered cabinet

had gathered like rambling gypsies on a hilltop,

the better to behold their smoking capital,

and Dolley Madison, disguised as a farmwife,

wandered in a wagon, up and down the roads,

for two days nearly lost in the countryside

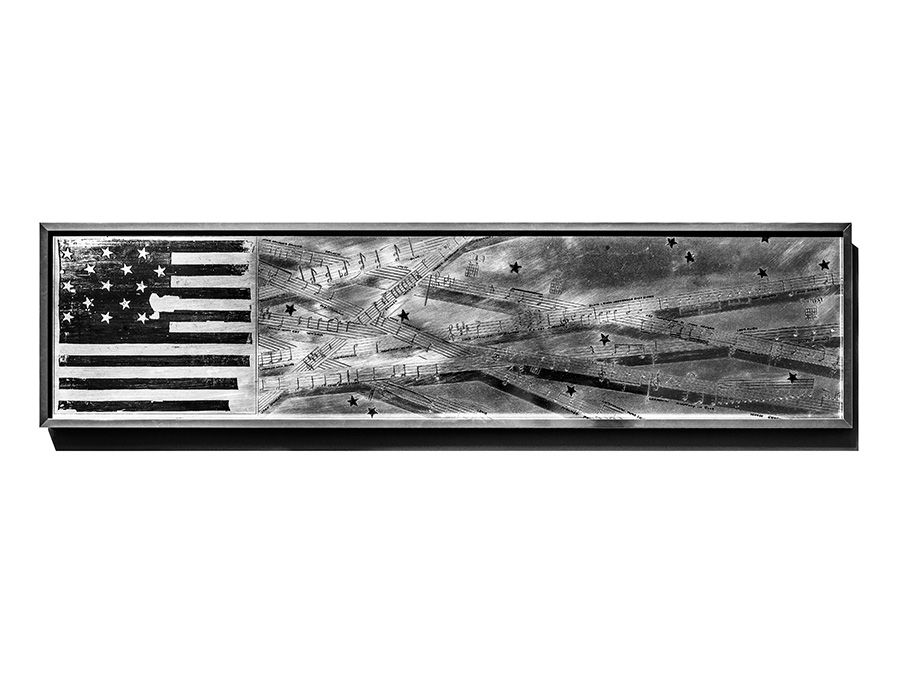

Pianist Rachel Grimes, who says "independence and freedom" are critical to artists, thought about Mary Pickersgill and "how deeply personal making the flag would have been."

The pioneering video artist has captured the ambient sound of cars passing and slowed it to one-quarter time, matching the flag image and creating a startling new perception of a familiar sight.

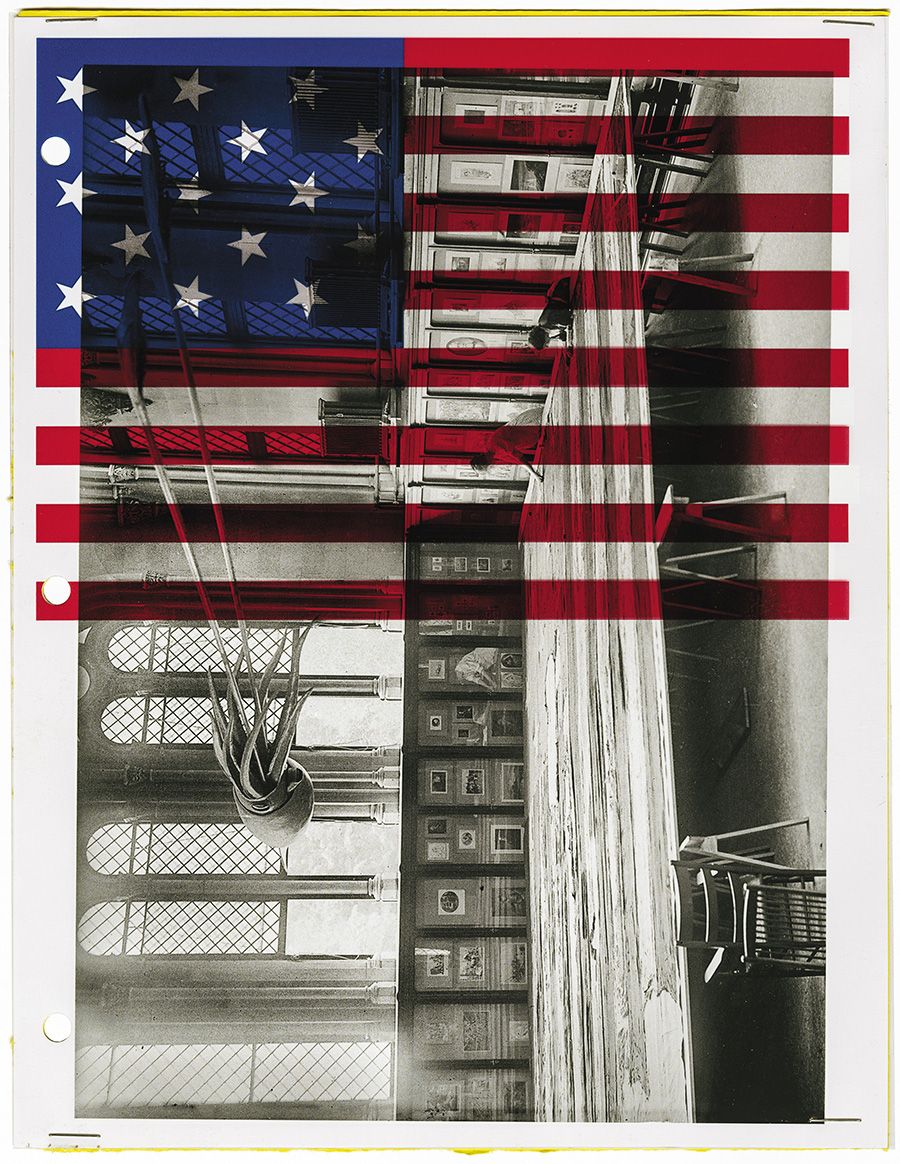

"This was just one person, making one thing," says artist and filmmaker Matt Mahurin of the original banner's fabricator. "And the object survived-- but more importantly, the ideas did."

"I was thinking about the state the world was in, being an American-- there's such a mix of positives and negatives," says jazz guitarist Mary Halvorson of her inspiration.