What is The Godfather Effect?

An obsessed film buff (and Italian-American) reflects on the impact of Francis Ford Coppola’s blockbuster trilogy

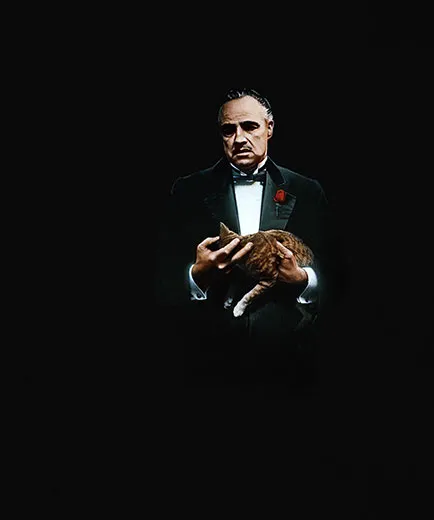

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/The-Godfather-Effect-Don-Vito-631.jpg)

Tom Santopietro was 18 years old in 1972, when he saw the movie The Godfather in a theater in his hometown of Waterbury, Connecticut. “I saw the movie for the first time with my parents,” recalls the author. “I have this very distinct memory of my father and I being wrapped up in it, and my mother leaning over and asking me, ‘How much longer is this?’”

Santopietro’s mother, Nancy Edge Parker, was of English descent, and, his father, Olindo Oreste Santopietro, was Italian. His grandparents Orazio Santopietro and Maria Victoria Valleta immigrated to the United States from southern Italy in the early 1900s. But it was seeing The Godfather trilogy that ultimately awakened Santopietro to his Italian roots and the immigrant experience.

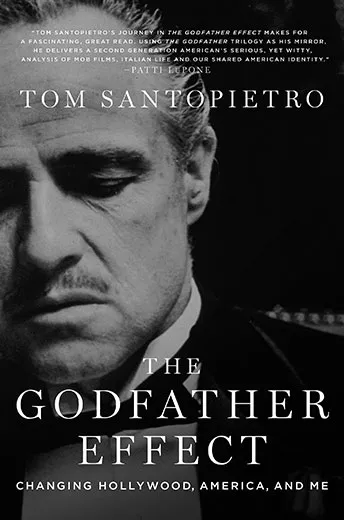

In his new book, The Godfather Effect, Santopietro looks at how the film saga portrays Italian-Americans and what that has meant for him, the film industry and the country.

How did the idea for this book—part memoir, part study of The Godfather films—form?

Like millions of other people around the world, I have been obsessed by The Godfather trilogy. I wanted to write about that. And, then, as I started writing about the films, I realized that I also wanted to write about other films depicting Italian-Americans and how horrible the stereotypes were. That made me start thinking about the journey that immigrants had made coming to America, the whys behind the journey and really the history of the mob. I started thinking about my own life, and I thought, I want to make this, in part, a memoir because I am half-Italian and half-English. There was a pull, because I had a very Italian name growing up in a very Anglo world.

When I saw The Godfather: Part II, and when ten minutes into the film there is the image of the young Vito on board the ship coming to America and passing by the Statue of Liberty, all of a sudden the light bulb went off. That image brought home to me my grandfather’s journey and how brave, at age 13, he was arriving here alone. At age 13, I was in a private school running around wearing my uniform and school tie, so removed from his experience. So it became not just a movie I loved as a movie lover, but a very personal depiction of the American journey for me.

How would you define the “Godfather effect”?

The film changed Hollywood because it finally changed the way Italians were depicted on film. It made Italians seem like more fully realized people and not stereotypes. It was a film in Hollywood made by Italians about Italians. Previously, it had not been Italians making the mobster films featuring Italian gangsters.

I feel it helped Italianize American culture. All of a sudden, everyone was talking about Don Corleone and making jokes about, “I am going to make you an offer you can’t refuse.” I think it helped people see that in this depiction of Italian-Americans was a reflection of their own immigrant experience, whether they were Irish or Jews from Eastern Europe. They found that common ground.

Then, of course, it changed me because when I saw what I felt was my grandfather on that ship coming to America, it was as if I was fully embracing my Italian-ness. I had never really felt Italian until then.

During the making of The Godfather, the Italian-American Civil Rights League organized protests, because it felt that the film would only reinforce the “Italian equals mobster” stereotype. And, to some extent, of course, it did. As you cite in the book, the Italic Institute of America released a report based on FBI statistics in 2009, stating that only 0.00782 percent of Italian-Americans possessed any criminal associations. And yet, according to a national Zogby poll, 74 percent of the American public believed that Italian-Americans have ties to the mob. Be honest, are you approaching this interview differently knowing my last name is Gambino?

I knew you weren’t a part of the Gambino crime family, but I have to tell you, I got a big smile. I thought, if I can be interviewed by a Gambino about my book about The Godfather, I am very happy.

You argue that The Godfather movies actually squash some stereotypes. Which ones?

Italian-Americans are very sensitive about their image in movies because it has traditionally been so negative, as either mobsters or rather simple-minded peasants who talk-a like-a this-a. I don’t like these stereotypical images, and yet, I love these films so much.

I think the vast majority of Italians have come to accept and actually embrace the film because I think the genius of the film, besides the fact that it is so beautifully shot and edited, is that these are mobsters doing terrible things, but permeating all of it is the sense of family and the sense of love. Where I feel that is completely encapsulated is in the scene toward the end of the first film when Don Corleone [Marlon Brando] and Michael Corleone [Al Pacino] are in the garden. It is really the transfer of power from father to son. Don Corleone has that speech: “I never wanted this for you.” I wanted you to be Senator Corleone. They are talking about horrible deeds. They are talking about transferring mob power. The father is warning the son about who is going to betray him. But you don’t even really remember that is what the scene is about. What you remember is that it is a father expressing his love for his son, and vice versa. That is what comes across in that crucial scene, and that is why I feel that overrides the stereotypical portrayal that others object to.

I think it squashed the idea that Italians were uneducated and that Italians all spoke with heavy accents. Even though Michael is a gangster, you still see Michael as the one who went to college, pursued an education and that Italians made themselves a part of the New World. These were mobsters, but these were fully developed, real human beings. These were not the organ grinder with his monkey or a completely illiterate gangster. It is an odd thing. I think to this day there are still some people who view the Italian as the “other”—somebody who is not American, who is so foreign. In films like Scarface [1932], the Italians are presented almost like creatures from another planet. They are so exotic and speak so terribly and wear such awful clothes. The Godfather showed that is not the case. In the descendant of The Godfather, which is of course “The Sopranos,” once again the characters are mobsters. But they are the mobsters living next door in suburban New Jersey, so it undercuts a bit that sense of Italian as the “other.”

What made the 1970s a particularly interesting backdrop for the release of The Godfather movies?

On the sociological level, we had been facing the twin discouragements of the Vietnam War and Watergate, so it spoke to this sense of disillusionment that really started to permeate American life at that time. I think also the nostalgia factor with the Godfather cannot be underestimated, because in the early ’70s (the first two films were in ’72 and ’74), it was such a changing world. It was the rise of feminism. It was the era of black power. And what The Godfather presented was this look at the vanishing white male patriarchal society. I think that struck a chord with a lot of people who felt so uncertain in this rapidly changing world. Don Corleone, a man of such certainty that he created his own laws and took them into his own hands, appealed to a lot of people.

In the book, you share some behind-the-scenes stories about the filming of the movies, including interactions between the actors and the real-life mafia. What was the best story you dug up about them intermingling?

That was really fun doing all the research on that. We all love a good Hollywood story. I was surprised that somebody like Brando, who was so famously publicity-shy and elusive, actually took the time to meet with a mafia don and show him the set of The Godfather. And that James Caan made such a point of studying the mannerisms of all the mobsters who were hanging around the set. I love that. You see it. Now when I watch the films again, all the gestures, all the details, the hands, the hitching of the pants, the adjusting of the tie, it is all just so smartly observed.

Both Mario Puzo, author of The Godfather, and Francis Ford Coppola, who directed the films, used some terms and phrases that were only then later adopted by actual mobsters. Can you give an example?

Absolutely. The term “the godfather.” Puzo made that up. Nobody used that before. He brought that into parlance. Here we are 40 years later and all the news reports of the mob now refer to so and so as the godfather of the Gambino crime family. Real-life mobsters now actually say, “I am going to make him an offer he can’t refuse.” That was totally invented by Puzo. I think these are phrases and terms that are not just used by the general public, but are also used by the FBI. So that is a powerful piece of art. The Godfather reaches its tentacles into so many levels of American life. I love the fact that it is Obama’s favorite movie of all time. I just love that.

Do you think anything has changed in the way audiences today react to the movie?

I think the biggest thing when you screen it today is that you realize it enfolds at a pace that allows you to get to know the characters so well. Today, because of the influence that started in the ’80s with music videos, it is all quick cuts, and they would never allow a film to unroll at this pace, which is our loss. We have lost the richness of character that The Godfather represents.

What do you think of television shows like “Mob Wives” and “Jersey Shore?” And, what effect do they have on Italian-American stereotypes?

I think “Mob Wives” and “Jersey Shore” are, in a word, terrible. The drama is usually artificial, heightened by both the participants and the editors for the dramatic purposes of television and hence are not real at all. They play to the worst stereotypes of Italian-American culture. Both shows center on larger-than-life figures to whom the viewing audience can feel superior. The audience condescends to these characters and receives their pleasure in that manner. It's not just “Jersey Shore” of course, because part of the pleasure for viewers of any reality show is feeling superior to contestants who sing badly, flop in their attempts to lose weight and the like. But the display of gavonne-like behavior on the two shows you mention results in both shows playing like 21st century versions of the organ grinder with his monkey—the Uncle Tom figure of Italian-Americans. It has been 100 years since the height of the immigrant and we're back where we started.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)