When Edgar Allan Poe Needed to Get Away, He Went to the Bronx

The author of ‘The Raven’ immortalized his small New York cottage in a lesser-known short story

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/07/e7/07e75b7e-88c5-4b3a-98a9-6b77f9930022/edgar-allan-poe-cottage-bronx.jpg)

Once upon a morning dreary, I left Brooklyn with eyes bleary, Wearily I took the subway to a poet's old forgotten home.

In 1844, Edgar Allan Poe and his young wife Virginia moved to New York City. It was Poe’s second time living in the city and just one of many homes for the peripatetic author. Unfortunately, after two years and several Manhattan addresses, Virginia fell ill with tuberculosis. With the hope that country air might improve her condition, or at least make her final days more peaceful, Poe moved the family out to a small, shingled cottage in the picturesque woods and green pastures of Fordham Village - better known today as the Bronx.

The six-room cottage was built in 1812 as worker’s housing for farm hands. Poe rented it from landowner John Valentine for $100 per year - no small sum for the constantly struggling writer who sold The Raven, his most famous work, for a flat fee of $8. During his time at the cottage, Poe cared for his ailing wife, who died three years after they moved in, and wrote some of his most celebrated poems, including the darkly romantic "Annabel Lee".

After Poe’s death in 1849, the cottage changed hands a few times and gradually fell in disrepair as the pastoral countryside became more and more urban. The area's upper class residents came to see it as an eyesore and an obstruction to progress, and by the 1890s Poe's house seemed destined for demolition. The growing controversy surrounding the cottage’s future was well-reported by The New York Times, which published a passionate article arguing in favor of preservation:

"The home of an author or a poet, whose memory has been marked for the honors that posterity alone confers, becomes a magnet for men and women the world over....The personal facts, the actual environment, the things he has touched and that have touched him are part of the great poet's wonder-work and to distort them or to neglect them is to destroy them entirely."

Eventually preservation prevailed, and a plan was enacted to build a park nearby and relocate the house just a block from its original site. Though the park was built, its centerpiece wasn't moved due to differences between dueling groups of preservationists and the prevarications of the building's new owner. In 1913, an agreement was reached and the house was relocated to its current site in what is now Poe Park.

Of course, the natural setting is long gone. Instead of apple orchards, the cottage is now surrounded on all sides by wide, multi-lane streets and tall apartment buildings like a rural oasis in the middle of a concrete ocean. It is the only surviving residential from old Fordham and a testament to preservation - not only of Poe’s history, but of New York’s history. Sometimes, for a few brief seconds when car horns quiet and traffic stops and the wind carries the sound of the bells bells bells bells of nearby Fordham University Church, you can imagine this place as it was during Poe’s life, a quiet respite from the city.

The cottage (as seen in the top image) is operated as a historic house museum by the Bronx County Historical Society. It is part of the Historic House Trust of New York City and listed on the the National Register of Historic Places. It underwent a stunning restoration in 2011, and was joined by a new visitor center that, while not used as such, is a beautiful complement to the cottage and architectural homage to the writer. Designed by Toshiko More Architect, the soaring new building’s black slate shingles and butterfly roof clearly seems to have been inspired by the Poe's avian harbinger of doom.

The interior is surprisingly spacious (at least by the standards of a writer living in contemporary New York) and furnished with period-accurate antiques that fit the description of the home given by visitors, as well as three appropriately Gothic items that actually belonged to Poe during his residency: the “rope bed” that Virginia died in, a rocking chair and a cracked mirror.

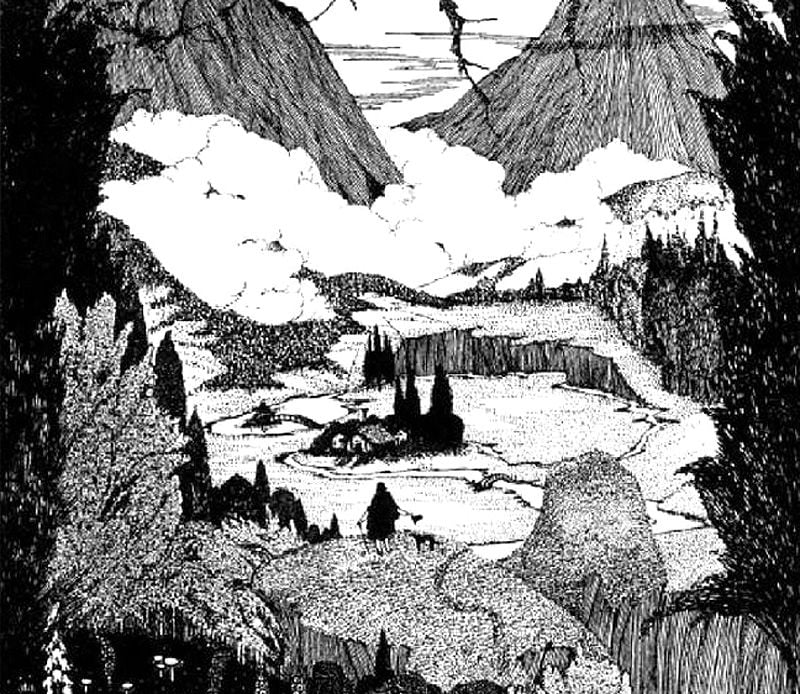

This modest building also served as the inspiration for the final Poe story published during the author’s life, “Landor’s Cottage,” which appeared in the June 9, 1849, issue of Flag of Our Union, four months before his death. A far cry from the tales of woe and horror Poe is widely known for, the story of “Landor’s Cottage” is quite simple: a man hiking through the bucolic setting of rural New York comes across a small house and marvels at its picturesque perfection, finding that it “struck me with the keenest sense of combined novelty and propriety — in a word, of poetry”. What follows is the narrator's depiction of the cottage. Warning: in the following excerpt, there’s no secret rooms, no woe-begotten protagonists or menacing visions.

Just pure, straightforward, even banal description:

The main building was about twenty-four feet long and sixteen broad- certainly not more. Its total height, from the ground to the apex of the roof, could not have exceeded eighteen feet. To the west end of this structure was attached one about a third smaller in all its proportions:-the line of its front standing back about two yards from that of the larger house, and the line of its roof, of course, being considerably depressed below that of the roof adjoining. At right angles to these buildings, and from the rear of the main one-not exactly in the middle-extended a third compartment, very small- being, in general, one-third less than the western wing. The roofs of the two larger were very steep-sweeping down from the ridge-beam with a long concave curve, and extending at least four feet beyond the walls in front, so as to form the roofs of two piazzas. These latter roofs, of course, needed no support; but as they had the air of needing it, slight and perfectly plain pillars were inserted at the corners alone. The roof of the northern wing was merely an extension of a portion of the main roof. Between the chief building and western wing arose a very tall and rather slender square chimney of hard Dutch bricks, alternately black and red:-a slight cornice of projecting bricks at the top. Over the gables the roofs also projected very much:-in the main building about four feet to the east and two to the west. The principal door was not exactly in the main division, being a little to the east-while the two windows were to the west. These latter did not extend to the floor, but were much longer and narrower than usual-they had single shutters like doors- the panes were of lozenge form, but quite large. The door itself had its upper half of glass, also in lozenge panes-a movable shutter secured it at night. The door to the west wing was in its gable, and quite simple-a single window looked out to the south. There was no external door to the north wing, and it also had only one window to the east.

The blank wall of the eastern gable was relieved by stairs (with a balustrade) running diagonally across it-the ascent being from the south. Under cover of the widely projecting eave these steps gave access to a door leading to the garret, or rather loft-for it was lighted only by a single window to the north, and seemed to have been intended as a store-room....

The pillars of the piazza were enwreathed in jasmine and sweet honeysuckle; while from the angle formed by the main structure and its west wing, in front, sprang a grape-vine of unexampled luxuriance. Scorning all restraint, it had clambered first to the lower roof-then to the higher; and along the ridge of this latter it continued to writhe on, throwing out tendrils to the right and left, until at length it fairly attained the east gable, and fell trailing over the stairs.

The whole house, with its wings, was constructed of the old-fashioned Dutch shingles-broad, and with unrounded corners. It is a peculiarity of this material to give houses built of it the appearance of being wider at bottom than at top-after the manner of Egyptian architecture; and in the present instance, this exceedingly picturesque effect was aided by numerous pots of gorgeous flowers that almost encompassed the base of the buildings.

Despite the Eden-like setting, it seems clear that Landor’s cottage is an idealized vision of Poe’s own Fordham residence. Beyond the formal resemblance, the interior layout of Landor’s cottage, described briefly by the narrator, is very similar to Poe’s cottage, with a kitchen, main room and bedroom on the first floor. It is also decorated in a manner keeping with the author’s own tastes, on which he elaborates in another lesser-known work, “The Philosophy of Furniture” (which I hope to elaborate on in a future post). Poe ends his architectural fiction by noting that another article may elaborate on the events that transpired at Landor’s cottage. Had he not died, perhaps we might have discovered more about the kind but enigmatic residence and his picturesque cottage.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)