When He Said “Jump…”

Philippe Halsman defied gravitas

The freezing of motion has a long and fascinating history in photography, whether of sports, fashion or war. But rarely has stop-action been used in the unlikely, whimsical and often mischievous ways that Philippe Halsman employed it.

Halsman, born 100 years ago last May, in Latvia, arrived in the United States via Paris in 1940; he became one of America's premier portraitists in a time when magazines were as important as movies among visual media.

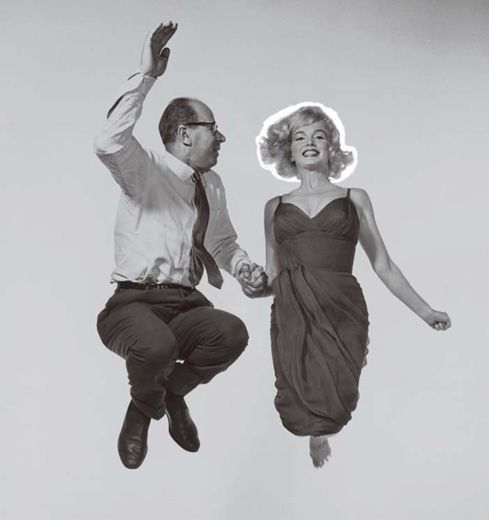

Halsman's pictures of politicians, celebrities, scientists and other luminaries appeared on the cover of Life magazine a record 101 times, and he made hundreds of other covers and photo essays for such magazines as Look, Paris Match and Stern. Because of his vision and vigor, our collective visual memory includes iconic images of Albert Einstein, Marilyn Monroe, Robert Oppenheimer, Winston Churchill and other newsmakers of the 20th century.

And because of Halsman’s sense of play, we have the jump pictures—portraits of the well known, well launched.

This odd idiom was born in 1952, Halsman said, after an arduous session photographing the Ford automobile family to celebrate the company's 50th anniversary. As he relaxed with a drink offered by Mrs. Edsel Ford, the photographer was shocked to hear himself asking one of the grandest of Grosse Pointe's grande dames if she would jump for his camera. "With my high heels?" she asked. But she gave it a try, unshod—after which her daughter-in-law, Mrs. Henry Ford II, wanted to jump too.

For the next six years, Halsman ended his portrait sessions by asking sitters to jump. It is a tribute to his powers of persuasion that Richard Nixon, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, Judge Learned Hand (in his mid-80s at the time) and other figures not known for spontaneity could be talked into rising to the challenge of...well, rising to the challenge. He called the resulting pictures his hobby, and in Philippe Halsman's Jump Book, a collection published in 1959, he claimed in the mock-academic text that they were studies in "jumpology."

Portraiture is one of the greatest challenges in photography, because the human face is elusive and often mask-like, with practiced expressions for the standard range of emotions. Some photographers accept these preset expressions—think of annual-report portraits of corporate officers—and others try to eliminate expression altogether, to get a picture as neutral as a wanted poster. Halsman was determined to show his sitters with their masks off but their true selves in place.

I had the good luck to spend time with Halsman in 1979, not long before he died, when I was writing the catalog for an exhibition of his work. I remember his way of delivering a funny line with perfect timing and a deadpan expression Jack Benny might have envied—and his delight at seeing how long it took for others to realize he was joking. For someone who spent his working hours with some Very Important People, this subversive streak must have been hard to contain. Sean Callahan, a former picture editor at Life who worked with Halsman on his last covers, thinks of the jump photos as a way for the photographer to unleash his sense of mischief after hours of work.

"Some of Halsman's sitters were more skillful at hiding their true selves than he was at cracking their facades, so he started to look at his jump pictures as a kind of Rorschach test, for the sitters and for himself," says Callahan, who now teaches the history of photography at the Parsons School of Design and Syracuse University, both in New York. "Also, I think Halsman came to the idea of jumping naturally. He was quite athletic himself, and well into his 40s he would surprise people at the beach by doing impromptu back flips."

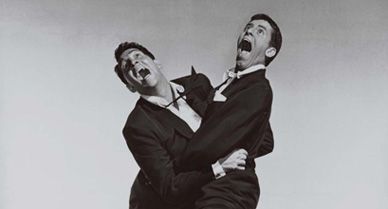

The idea of jumping must have been planted in Halsman's mind even before his experience with the Fords. In 1950, NBC television commissioned him to photograph its lineup of comedians, including Milton Berle, Red Skelton, Groucho Marx and a fast-rising duo named Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis. Halsman noticed that some of the comedians jumped spontaneously while staying in character, and it was unlikely that any of them jumped with more antic enthusiasm than Martin, a crooner and straight man, and Lewis, who gave countless 10-year-old boys a class clown they could look up to.

It may seem like a stretch to go from seeing funnymen jumping for joy to persuading, say, a Republican Quaker vice president to take the leap, but Halsman was always on a mission. ("One of our deepest urges is to find out what the other person is like," he wrote.) And like the true photojournalist he was, Halsman saw a jumpological truth in his near-perfect composition of Martin and Lewis.

In the book, Martin and Lewis appear on a right-hand page, juxtaposed with other famous pairs on the left: songwriters Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein, and publishers Richard L. Simon and M. Lincoln Schuster. "Each of the four men on the left jumps in a way which is diametrically opposed to the jump of his partner," Halsman wrote. "Their partnerships were lasting and astonishingly successful. The two partners on the right, whose jumps are almost identical, broke up after a few years."

Owen Edwards is a former critic for American Photographer magazine.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)