When Modern Art Met the Classic Chess Set

How far can you push the design of a knight before it stops looking like a knight?

![]()

Last week we published a history of the Staunton chess set, which was developed, in part, out of a need to standardize pieces for international competition. In a response on his blog, Jason Kottke published some terrific images of beautiful pre-Staunton sets –the St. George, the Selenus, and the Regence– and explained some of the confusion that prompted the creation of the Staunton. While following up on some of these early chess sets, I learned that there is a trove of artist-designed chess sets in the archives of the Museum of Modern Art. The largely minimalist chess pieces, created by artists including Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp and Josef Hartwig, represent an attempt to strip down each piece to its most essential components: what is the absolute least a knight can be to still be read as a knight? The results are striking, although often just as confusing as the idiosyncratic pre-Staunton sets that proliferated throughout Europe during the 18th century.

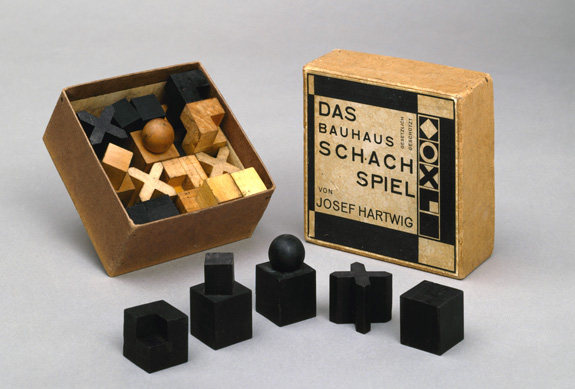

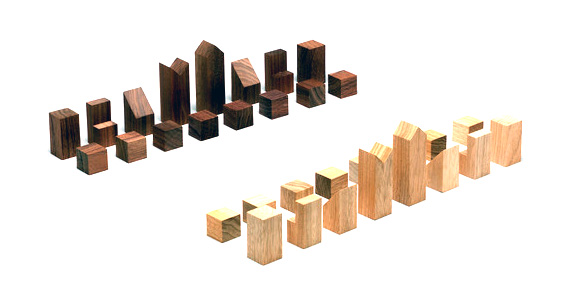

Sculptor Josef Hartwig designed his chess set (above two images) while teaching at the Bauhaus in 1924. It embodied the school’s tenets that an object must be practical, durable, inexpensive and beautiful. Hartwig’s design reduced the pieces to the most basic components of artistic construction: line, square and circle. Though they are incredibly abstract, each well-crafted piece, originally sculpted from pear wood, has been designed to describe its movement on the board. The bishop, for example, is a simple X, denoting its diagonal movement. Every aspect of the Bauhaus set was given consideration, even the packaging designed by Hartwig’s colleague Joost Schmidt. It truly is, in the Bauhaus tradition, a union of art and craft. The pieces are stripped of any symbolic meaning and reduced to pure form. Their designations –bishop, knight, king– become irrelevant. All that matters was movement, which is made tangible as the identifying characteristic of each piece.

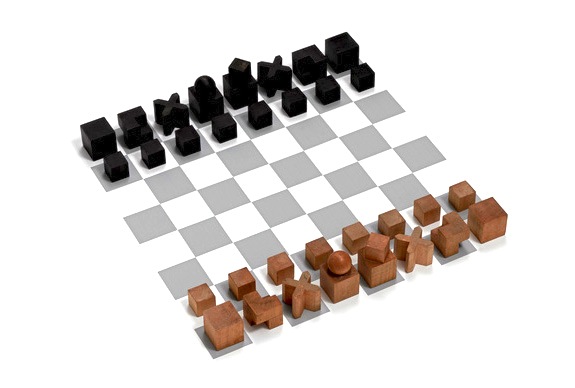

Even more reductive is this 1966 best designed by Lanier Graham. Perhaps most noteworthy on this set are the king and queen, whose tops are inverse versions of one another – a sort of phallic point on the king and, conversely, a yonic ‘v’ for the queen. Like Hartwig’s, Graham’s pieces fit perfectly, tanagram-like into its box.

A chess set designed by Man Ray in 1920 (original image: F. Martin Ramin via The Wall Street Journal)

Man Ray designed a set using mostly conic and curvilinear abstract forms. While his pieces are beautiful, they seem to be abstract for abstraction’s sake, rather than carry any built-in meaning. In fact, the pieces are a rather personal reflection of the artist himself, or rather, the artists space. Each piece was inspired by an object in his studio used for inspiration or still-life arrangement. The knight, for example, is the finial of a violin.

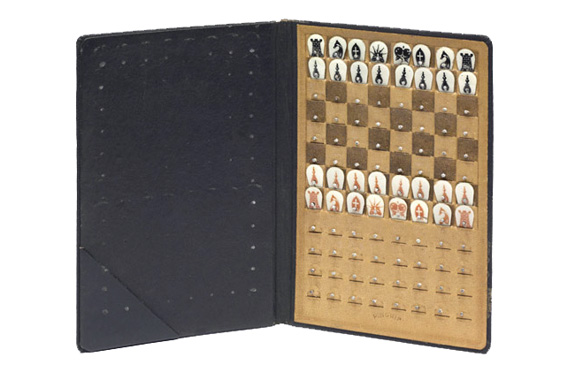

Man Ray played many chess matches against his friend and fellow artist Marcel Duchamp, for whom chess was, perhaps more than any artist past or present, a profound muse. More that that. Chess consumed Duchamp. In the 1920s, it was said that he abandoned art for the world of competitive chess. While he never truly stopped producing art, Duchamp did indeed compete in professional tournaments, even entering the several championships and earning the status of chess master. He not only drew and painted chess players, but encoded messages in his work that could only be read by chess players. Duchamp published a book on endgame theory the title of which sounded like one of his paintings or sculptures: Opposition and Sister Squares are Reconciled. He designed chessmen and even created his own pocketbook chess sets, ensuring that he would never be without a board. In an obituary published in The New York Times, it was said that Duchamp’s life-long enthusiasm for the game inspired his fellow artists to create their own sets. For Duchamp, art and chess were one and the same. “From my close contact with artists and chess players,” he has famously said, “I have come to the personal conclusion that while all artists are not chess players, all chess players are artists.”

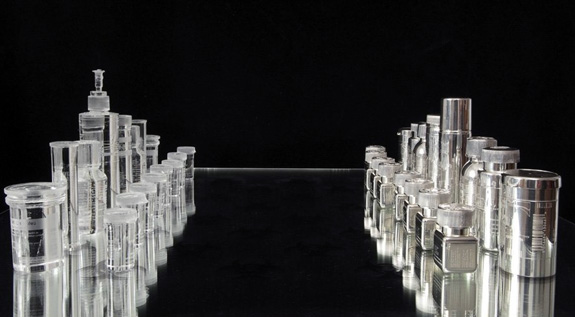

A chess set designed by Damien Hirst for the Saatchi Gallery (image: frameweb)

These artistic chess are not strictly the purview of the middle of the century. Last year, London’s Saatchi Gallery commissioned sixteen artists, including Maurizio Cattelan, Damien Hirst, Barbara Kruger, and Rachel Whiteread, to create their own vision of the game of kings. The results are incredibly diverse. Hirst’s set (above image) is made entirely from medicine bottles.

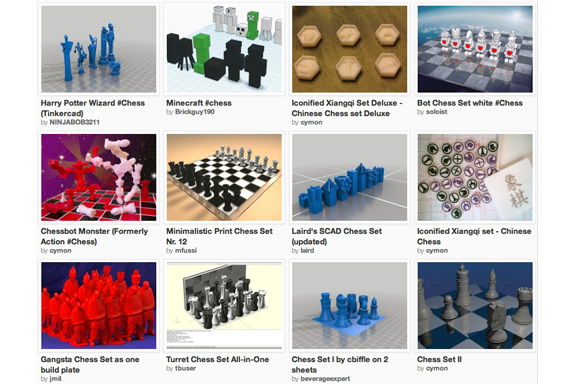

A sampling of chess sets created by 3D printing hobbyists for a makerbot design competition (image: thingverse)

But even more cutting edge than high-art chess pieces are home-made ones. Relatively cheap 3D printing, combined with free design software, means that almost anyone can create their own chess sets. Last year, 3D printing pioneers Makerbot issued a chess set design challenge. Nearly one hundred diverse entries were posted online, including everything from variations of the traditional Staunton to a particularly innovative set of pieces that join together Voltron-like to form a chess robot.

With its nearly infinite combination of moves, its symbolic pieces, and its romantic terminology, it’s no wonder that chess has captured the imagination of artists throughout history. And there’s absolutely no doubt that the game will continue to challenge and inspire.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)