Why Taxidermy Is Being Revived for the 21st Century

A new generation of young practitioners is leading a resurgence in this centuries-old craft

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ba/04/ba049de0-e1fa-4929-a571-46475550f918/taxidermy-65718.jpg)

“Ahhh, this polyurethane is setting up too quick,” exclaims Allis Markham, proprietor of Prey Taxidermy in Los Angeles. “Sorry, I’m molding bodies right now,” she adds, apologizing for the interruption in our conversation.

Markham makes a living as a very busy taxidermist.

She does regular commission work—like what she is doing right now, preparing roosters for the storefront of a client’s Los Angeles floral boutique. Markham also teaches classes on nights and weekends at Prey, her taxidermy workshop, where she is usually “elbow deep in dead stuff”—“Birds 101” and “Lifesize Badger, Porcupine, Fox” are just two options on their very full monthly schedule. She also finds time to volunteer at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles, where she previously was on staff.

Markham is part of a modern resurgence in the centuries-old craft of taxidermy. At 32, she is a successful and celebrated representative of the new cohort of taxidermists, who are young, academically driven and largely female. In May, Markham competed in the World Taxidermy & Fish Carving Championships (WTC) in Springfield, Missouri, where she received a Competitors’ Award (given to the participants with the best collections of work) in the event's largest division.

With more than 1,200 attendees, this year’s WTC was bigger than ever before. About 20 percent of the attendees at the event were women. And when Markham and ten of her students—all women—entered their work at WTC, it made waves at the three-decade-old tournament. “We stood out, that’s for damn sure,” Markham says with a laugh. Their presence was met with excitement, respect and hope. “I’ll tell you, there were more young women than I had ever seen [at the WTC]. I think it’s wonderful," says event judge Danny Owens, regarded as one of the best bird taxidermists on Earth. "If the young generation doesn’t get involved, then our industry will eventually just die out.”

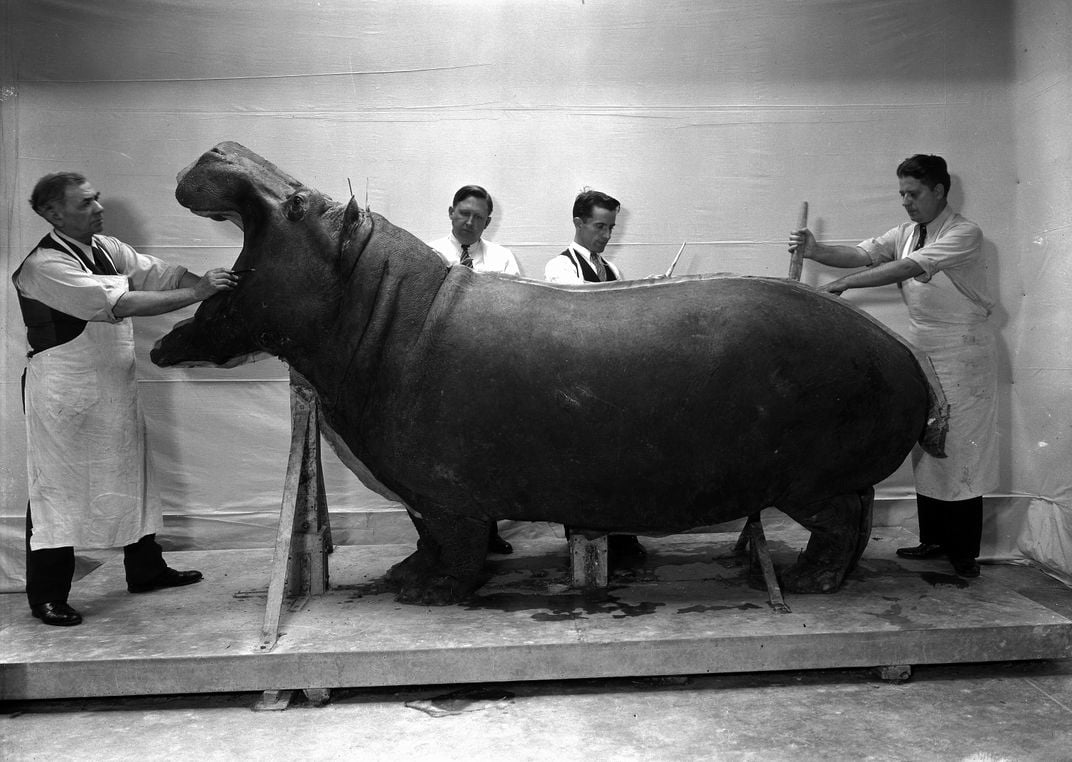

The practice of taxidermy began in Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries as a means of preserving specimens collected by world-traveling explorers. Oftentimes, these specimens would become part of a rich collector’s “cabinet of curiosities,” bringing a dash of wonder and mystery to viewers who knew nothing of the far reaches of the world.

During the early days of taxidermy, protecting the finished work from insect attacks seemed like a nearly insurmountable challenge. Avid bird skin collector Jean-Baptist Bécœur changed all of that when he developed arsenical soap, a combination of pulverized arsenic, white soap and “unslacked lime,” or calcium oxide. Formulated around 1743, Bécœur kept the chemical recipe a secret during his lifetime. Upon his death, other taxidermists and collectors noticed the staying power of Bécœur’s collection and performed a little reverse engineering. By the mid-19th century, museums and private collectors were widely using arsenical soap to protect their taxidermy specimens, leading to a golden age of taxidermy that spanned from about 1840 through the dawn of World War I.

“Arsenic is a very effective insecticide because it decomposes when damp, so effectively it’s self-fumigating. It was a very effective way of dealing with insects, which historically was the biggest problem in preserving taxidermy,” says Pat Morris, the author of A History of Taxidermy: Art, Science, and Bad Taste. Despite its common usage during the Victorian era, arsenic was known to be highly poisonous back then. Today arsenic is banned in almost every country, and Borax and tanning techniques are often used as alternatives.

Before color photography and the growth in leisure travel, taxidermy specimens allowed scientists, naturalists, collectors and the curious to study life-like 3D representations of animals they otherwise would have never encountered. In his 1840 “Treatise on Taxidermy,” famed British zoologist William Swainson wrote, “Taxidermy is an art absolutely essential to be known to every naturalist since, without it, he cannot pursue his studies or preserve his own materials.” Taxidermy, especially of birds, was also popular as Victorian-era home decoration and a way for hunters to display trophies from their latest adventure.

Taxidermy was so prevalent throughout both America and England during the late 19th century, according to Morris, that a taxidermist could be found in nearly every town. Often, there were several, all competing for clients. According to The History of Taxidermy, the London census of 1891 shows that 369 taxidermists operated in the English capital city alone, about one taxidermist for every 15,000 Londoners. “Taxidermists [during the late 19th century] were treated as just another person who did a job, like a hair barber or a butcher or a window cleaner,” says Morris. “They were given a job to do and they did it.”

After the Great War, several factors played into the decline of taxidermy, but mainly the demand evaporated as new technologies came on the scene. The turn of the 20th century brought the age of amateur photography, thanks to George Eastman and his Brownie camera. In 1907, the Lumière brothers debuted their autochrome process in Paris, forever changing how photographs were colorized. Mantles that once were decorated with brightly colored taxidermy birds were now being decorated more cheaply with photos. Photography aided development of birding guides, first popularized by Chester A. Reed’s Bird Guides, and that also contributed to the field's waning popularity. Amateur birders and professional ornithologists had definitive reference texts with detailed specifics for thousands of birds, stripping much of the scientific need for private collections.

In addition, many of the big American museums—such as the Field Museum in Chicago and the American Museum of Natural History in New York—were done filling up their elaborate habitat dioramas by the 1940s. Finally, big game hunting became much less socially acceptable after World War II. As the 20th century progressed, the illegal ivory and fur market became the main perpetrator for the declining numbers of African species, and many governments passed wildlife conservation acts.

Still, taxidermy didn’t completely die off. From 1972 to 1996, Larry Blomquist owned one of the largest taxidermy studios in the southeast United States. Today he’s retired but still runs the trade journal Breakthrough Magazine (with a subscription base of about 8,000) and organizes the World Taxidermy Championships—he was a judge at the very first one in 1983.

Blomquist says he has undoubtedly seen an uptick of interest in taxidermy in recent years: “There definitely has been a resurgence in interest in taxidermy in the general public ... we get calls on a weekly basis, to be honest with you, from various news sources to talk about taxidermy ... I love it.” He also notes that more women than ever before are showing interest in the craft. “While women have been involved in taxidermy for many, many years,"—he specifically points out Milwaukee Public Museum’s Wendy Christensen—"I do see more females interested in taxidermy than we saw 20 or 25 years ago,” he says.

Jennifer Hall is a paleontologist and scientific illustrator who heard about Markham’s class through word of mouth. She began studying with her about a year ago and now works for her as Prey’s studio manager. Hall has her own theory about why women are helping to bring taxidermy back from the dead: “Suddenly, women are breaking through in certain areas that they haven’t been in the past. Not that there weren’t women in the traditionally male-dominated world of taxidermy, but in general there is this turnover in society, and women are really starting to break down those barriers.”

But why has taxidermy in particular become such a popular hobby? Blomquist thinks it has something to do with the increased availability of information online. But anecdotal evidence also points to something much deeper than the rise of social media and the Internet.

For a number of years, Markham was the director of social media strategy for the Walt Disney Corporation. “I really felt liked I lived at a computer and at my desk,” she says. So in 2009, she took two weeks of vacation to attend taxidermy school in Montana. After completing her first specimen, a deer, she felt a complete sense of accomplishment. “It existed in the real world and not on a computer,” says Markham. Soon after, she quit her job at Disney and began volunteering at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles, under the tutelage of Tim Bovard, who now also teaches classes at Prey. The volunteer opportunity turned into a job and then into a career.

Morris agrees that this sense of getting back in touch with the physical world is at the core of taxidermy’s rebirth. ”I think people have been insulated from animal specimens for so long, that when someone picks up a bone or skull, they are completely knocked out by it, by what an incredible, wonderful thing it is. The same goes for a dead bird ... when it is physically in your hand, you want to preserve it ... it becomes special.”

For many modern practitioners, taxidermy has become a hip and trendy art form, with everyone trying to find ways to stand out. Knowledge of taxidermy also still has scientific uses, such as restoring museum displays or extracting DNA from the preserved bodies of long-lost or endangered species.

The type of taxidermy Markham practices falls in the middle of this Venn diagram of art and science: While she considers every piece she does art, her training helps her prioritize making museum-quality, anatomically correct work. Markham also prides herself on creating pieces that are both accurate and ethical, meaning that no animal worked on at Prey ever died solely for taxidermy. Her European starlings, for instance, come from a Wisconsin bird abatement business that handles the invasive species. Markham admits that, often times, people are confused about why she wants a bunch of dead birds, “Oh, yeah. People get creeped out. Until they get to know you and where you are coming from, they think you don’t like animals or are blood-thirsty.”

Still, every month Markham is adding to her schedule of classes at Prey. To help out, she has recruited instructors from the connections she made at the taxidermy championships. Some of the heavy hitters in the field, such as Tony Finazzo and Erich Carter, are planning on joining Markham in Los Angeles to teach their own specialized courses. And all of Markham’s classes, both the ones she teaches herself and the ones with guest instructors, are selling out on a consistent basis. Women continue to dominate the clientele. “Quite frankly, if I have more than two guys in one of my classes, I’m shocked ... My classes are nearly all women,” says Markham.

Taxidermy: alive and kicking.