Woody Guthrie’s Music Lives On

More than 40 years after the celebrated folk singer’s death, a trove of 3,000 unrecorded songs is inspiring musicians to lay new tracks

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Woody-Guthrie-playing-guitar-631.jpg)

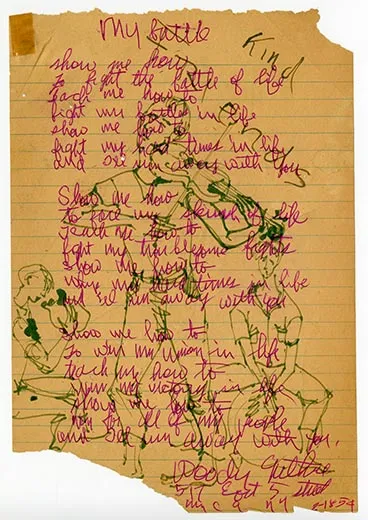

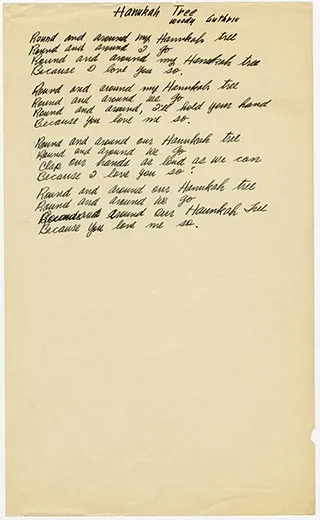

Singer-songwriter Jonatha Brooke saw an impish grin, and a twinkle in Nora Guthrie’s eye as Guthrie handed her the sheet with lyrics Woody Guthrie penned nearly 50 years ago. At the bottom was the notation to “finish later.” He never got the chance.

All ya gotta do is touch me easy

All ya gotta do is touch me slow

All ya gotta do is hug me squeeze me

All ya gotta do is let me know

Brooke figured it was some kind of test. This wasn’t what she expected from the author of Dust Bowl ballads and rousing working-man blues. She’d been invited to the midtown Manhattan offices of the Woody Guthrie Archives, administered by Nora Guthrie, his daughter, to set a few of his lyrics to music for a 2007 benefit.

“I said, yeah, maybe I could do something with that,” she recalls, laughing. “Maybe that’s going to be Woody’s first disco song.”

Guthrie knew then she’d made the right match. Woody Guthrie may have been known mostly as a lyrical provocateur, but he wrote about everything from A to Z, from diapers to sex, and she’d been looking for someone to bring his romantic side alive.

Brooke was “pretty ignorant” of Woody Guthrie’s life before she spent three days a week for a month poring over 26 folders organized alphabetically by title. “You’re just stunned by what you’re looking at,” she says. “The original ‘This Land Is Your Land' or the Coulee Dam song.”

She quickly started plotting how to transform the invitation into a larger project, succeeding when she brought Guthrie to tears with a performance of “All You Gotta Do” at the Philadelphia Folksong Society benefit in 2007. (When Guthrie heard “All You Gotta Do” at the benefit, it cemented the opportunity for Brooke to return and look through more lyrics to do a full album.) “The Works,” featuring ten tracks composed by Brooke but with Woody’s lyrics, was released last year. Over the days with Woody, Brooke developed a crush. “I said, ‘I’m in love with your father’,” she recalls telling Nora. “‘It’s a little bit morbid and kinda strange. Are you cool with this? She’d be like, ‘Oh yeah, everybody falls in love with Woody.’”

“I think Nora was tickled I was drawn to the really romantic and spiritual songs. It wasn’t topical or political to me,” Brooke says. “It was personal.”

Brooke is one of a few dozen contemporary songwriters who have been invited to put music to Woody Guthrie’s words, words he left behind in notebooks and on napkins, onion paper, gift-wrap, and even place mats. Huntington’s disease cut short his performing career in the late 1940s, leaving nearly 3,000 songs never recorded (he died in 1967). One of the most acclaimed covers of the unrecorded works was the collaboration between British neo-folkie Billy Bragg and alt-country rockers Wilco for “Mermaid Avenue,” released in 1998.

In recent years, contemporary folkies like Ellis Paul, Slaid Cleaves and Eliza Gilkyson have released songs mined from the archives. “Ribbon of Highway -- Endless Skyway,” an annual musical production celebrating Woody Guthrie’s songs and life travels, annually features Jimmy LaFave, a Texas-based singer-songwriter, and a changing cast of other performers including Sarah Lee Guthrie, Woody’s granddaughter, and her husband, Johnny Irion. She recently released “Go Waggaloo,” a children’s album featuring three songs with her grandfather’s lyrics on the Smithsonian Folkways label (which also maintains an archive of original Woody Guthrie recordings, lyrics, artwork and correspondence.

Dipping into both archives for the children’s album was a chance for Sarah Lee Guthrie to work with the grandfather she never knew. She intends to revisit the archives. “I’m hanging out with him; we’re writing a song together,” she says. “It’s pretty magical.”

The matchmaker for most of these collaborations is Nora Guthrie, Woody’s youngest, born in 1950. She describes the process as “very intuitive and organic” and jokes that she’s “in touch with everyone on the planet” about using the archives. Her father, she notes, wrote “all or none” under religion on the birth certificates of his children.

“Everything is all about all or none,” she says. “Not just religion. Music is all or none.” So the metal punk revolutionary Tom Morello, who also performs as the political folkie the Nightwatchman, has cut a song. So have the Klezmatics, a klezmer band that released “Wonder Wheel,” an album celebrating Woody Guthrie’s Jewish connection (his mother-in-law, Aliza Greenblatt was a famous Yiddish poet) and the Dropkick Murphys, an Irish-American Celtic band. Lou Reed, Jackson Browne, Ani DiFranco, Van Dkye Parks, the late Chris Whitley, and Nellie McKay have all worked with the lyrics on a project orchestrated by the bassist Rob Wasserman over the past decade.

“I’m trying to find who he would be interested in today,” she says. “Who would he want to see eye to eye? Who would he want to have a drink with? Who would he hang out with? Knowing him, I just try to expand that out to today’s world.”

The material that formed the foundation of the archives was crammed into boxes for years in a Queens basement. After a flood in the late 1960s, the boxes were moved to the Manhattan office of Harold Leventhal, the longtime manager of Woody Guthrie’s estate. They languished there for years until Leventhal, contemplating retirement, called in Nora Guthrie and said she should get to know the family business. She volunteered once a week, typing labels and doing the mail.

One day he put a box on her desk and told her to look through it. It was stuffed with her father’s work, lyrics, letters, art and diaries. There was the original of “This Land Is Your Land,” all six verses. She called the Smithsonian seeking recommendations about how to handle the material. When the Institution’s Jorge Arevalo Mateus visited, the first thing he suggested was that she move the coffee on her desk away from the copy of “This Land.” He stayed to become curator of the archives.

Then she started reading. “Everything I pulled out was something I’d never seen before or heard of before,” she says.

She started showing material to Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie’s longtime co-conspirator, and he had never seen a lot of it. “That’s when things got goofy,” she says. “Suddenly, there was a parting of the waters.”

She assumed folklorists had documented everything Woody, but he was so prolific that that was impossible. She went to a conference in 1996 and sat in the back, listening to scholars who described her father as someone who didn’t believe writing “moon croon June songs.“ She knew better. “I felt like I was at a conference on Picasso and nobody was talking about the Blue Period because they didn’t know about it. There was a huge gap in history and in the story.”

Growing up she only knew Woody Guthrie the patient, not Woody Guthrie the performer. Now, she can help give life to creations he never had the chance to record. “He left all these songs behind because of Huntington’s disease and because of tragedies in his life. It was such an interrupted life,” she says. When a parent passes away and leaves you stuff, your responsibility is to figure out how to pass it on. For me, it’s a bunch of songs.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jim-morrison-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jim-morrison-240.jpg)