Wyeth’s World

In the wake of his death, controversy still surrounds painter Andrew Wyeth’s stature as a major American artist

Editor's Note, January 16, 2009: In the wake of Andrew Wyeth's death at the age of 91, Smithsonian magazine recalls the 2006 major retrospective of Wyeth's work and the ongoing controversy over his artistic legacy.

In the summer of 1948 a young artist named Andrew Wyeth began a painting of a severely crippled woman, Christina Olson, painfully pulling herself up a seemingly endless sloping hillside with her arms. For months Wyeth worked on nothing but the grass; then, much more quickly, delineated the buildings at the top of the hill. Finally, he came to the figure itself. Her body is turned away from us, so that we get to know her simply through the twist of her torso, the clench of her right fist, the tension of her right arm and the slight disarray of her thick, dark hair. Against the subdued tone of the brown grass, the pink of her dress feels almost explosive. Wyeth recalls that, after sketching the figure, “I put this pink tone on her shoulder—and it almost blew me across the room.”

Finishing the painting brought a sense of fatigue and let-down. When he was done, Wyeth hung it over the sofa in his living room. Visitors hardly glanced at it. In October, when he shipped the painting to a New York City gallery, he told his wife, Betsy, “This picture is a complete flat tire.”

He couldn’t have been more wrong. Within a few days, whispers about a remarkable painting were circulating in Manhattan. Powerful figures of finance and the art world quietly dropped by the gallery, and within weeks the painting had been purchased by the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). When it was hung there in December 1948, thousands of visitors related to it in a personal way, and perhaps somewhat to the embarrassment of the curators, who tended to favor European modern art, it became one of the most popular works in the museum. Thomas Hoving, who would later become director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, recalls that as a college student he would sometimes visit the MoMA for the sole purpose of studying this single painting. Within a decade or so the museum had banked reproduction fees amounting to hundreds of times the sum—$1,800—they had paid to acquire the picture. Today the painting’s value is measured in the millions. At age 31, Wyeth had accomplished something that eludes most painters, even some of the best, in an entire lifetime. He had created an icon—a work that registers as an emotional and cultural reference point in the minds of millions. Today Christina’s World is one of the two or three most familiar American paintings of the 20th century. Only Grant Wood, in American Gothic, and Edward Hopper, in one or two canvases such as House by the Railroad or Nighthawks, have created works of comparable stature.

More than half a century after he painted Christina’s World, Wyeth is the subject of a new exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The first major retrospective of the artist’s work in 30 years, the exhibition, on display through July 16, was co-organized with the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, where it opened in November 2005. A concurrent exhibition at the Brandywine River Museum in Wyeth’s hometown of Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, featuring drawings from the artist’s own collection, is also on view through July 16.

The title of the Philadelphia exhibition, “Andrew Wyeth: Memory and Magic,” alludes not only to the first major exhibition in which Wyeth was included, the “Magic Realism” show of 1943 at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, but also to the importance of magic and memory in his work. “Magic! It’s what makes things sublime,” the artist has said. “It’s the difference between a picture that is profound art and just a painting of an object.” Anne Classen Knutson, who served as curator of the exhibition at the High Museum, says that Wyeth’s “paintings of objects are not straightforward illustrations of his life. Rather, they are filled with hidden metaphors that explore common themes of memory, nostalgia and loss.”

Over a career that has spanned seven decades, Wyeth, now 88 and still painting, has produced a wealth of technically stunning paintings and drawings that have won him a huge popular following and earned him a considerable fortune. But widespread acceptance among critics, art historians and museum curators continues to elude him, and his place in history remains a matter of intense debate. In 1977, when art historian Robert Rosenblum was asked to name both the most overrated and underrated artist of the century, he nominated Andrew Wyeth for both categories. That divergence of opinion persists. Some see Wyeth as a major figure. Paul Johnson, for example, in his book Art: A New History, describes him as “the only narrative artist of genius during the second half of the twentieth century.” Others, however, decline even to mention Wyeth in art history surveys. Robert Storr, the former curator of painting at MoMA, is openly hostile to his work, and Christina’s World is pointedly omitted from the general handbook of the museum’s masterworks.

The current exhibition has only stirred the debate. “The museum is making a statement by giving Wyeth this exhibition,” says Kathleen Foster, the Philadelphia Museum’s curator of American art. “So I think it’s clear that we think he’s worth this big survey. The show aims to give viewers a new and deeper understanding of Wyeth’s creative method and his accomplishment.”

Andrew Wyeth was born in Chadds Ford in 1917, the fifth child of artist NC Wyeth and his wife, Carolyn Bockius. One of the most notable American illustrators of his generation, NC produced some 3,000 paintings and illustrated 112 books, including such classics as Treasure Island, Kidnapped and The Boy’s King Arthur.

With a $500 advance from Scribner’s for his illustrations for Treasure Island, NC made a down payment on 18 acres of land in Chadds Ford, on which he built a house and studio. As his illustrations gained in popularity, he acquired such trappings of wealth as a tennis court, a Cadillac and a butler. Ferociously energetic and a chronic meddler, NC attempted to create a family life as studiously as a work of art, carefully nurturing the special talents of each of his children. Henriette, the eldest, became a gifted still-life and portrait artist; Nathaniel became a mechanical engineer for DuPont; Ann became an accomplished musician and composer; Carolyn became a painter.

Andrew, the youngest child, was born with a faulty hip that caused his feet to splay out when he walked. Frequently ill, he was considered too delicate to go to school. Instead, he was educated at home by a succession of tutors and spent much of his time making drawings, playing with his collection of toy soldiers—today he has more than 2,000—and roaming the woods and fields with his friends, wearing the costumes his father used for his illustrations. According to biographer Richard Meryman in his book Andrew Wyeth: A Secret Life, Andrew lived in awe of his powerful, seemingly omniscient father, who was nurturing but had a volatile temper. Famously elusive and secretive as an adult, Andrew likely developed these qualities, says Meryman, as a defense against his overbearing father. “Secrecy is his key to freedom,” writes Meryman, one of the few non-family members in whom the artist has confided.

Until Andrew’s adolescence, his father provided no formal artistic instruction. NC somehow sensed a quality of imagination in his son’s drawings that he felt shouldn’t be curbed. Andrew’s last pure fantasy picture, a huge drawing of a castle with knights laying siege, impressed his father, but NC also felt that his son had reached the limit of what he could learn on his own.

On October 19, 1932, Andrew entered his father’s studio to begin academic training. He was 15 years old. By all accounts, NC’s tutorials were exacting and relentless. Andrew copied plaster casts. He made charcoal drawings of still-life arrangements, drew and redrew a human skeleton—and then drew it again, from memory. Through these and other exercises, his childhood work was tempered by solid technical mastery. “My father was a terrific technician,” says Wyeth. “He could take any medium and make the most of it. Once I was making a watercolor of some trees. I had made a very careful drawing and I was just filling in the lines. He came along and looked at it and said, ‘Andy, you’ve got to free yourself.’ Then he took a brush and filled it with paint and made this sweeping brushstroke. I learned more then from a few minutes of watching what he did than I’ve ever learned from anything since.” After two years of instruction, his father set him loose.

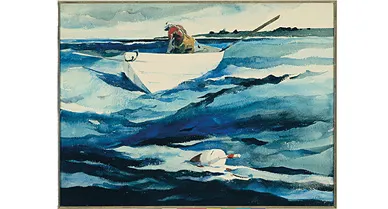

Andrew’s first notable works were watercolors of Maine that reflect the influence of Winslow Homer. Wyeth began producing them in the summer of 1936, when he was 19. Fluid and splashy, they were dashed off rapidly—he once painted eight in a single day. “You have a red-hot impression,” he has said of watercolor, “and if you can catch a moment before you begin to think, then you get something.”

“They look magnificent,” his father wrote to him of the pictures after Andrew sent a cluster of them home to Chadds Ford. “With no reservations whatsoever, they represent the very best watercolors I ever saw.” NC showed the pictures to art dealer Robert Macbeth, who agreed to exhibit them. On October 19, 1937, five years to the day after he had entered his father’s studio, Andrew Wyeth had a New York City debut. It was the heart of the Depression, but crowds packed the show, and it sold out on the second day—a phenomenal feat. At the age of 20, Andrew Wyeth had become an art world celebrity.

But Wyeth had already begun to feel that watercolor was too facile. He turned to the Renaissance method of tempera—egg yolk mixed with dry pigment—a technique he had learned from his sister Henriette’s husband, Peter Hurd, the well-known Southwestern painter. By 1938, Wyeth was devoting most of his attention to the medium. He was also gradually emerging from his father’s shadow, a process that was hastened by the arrival of a new person in his life, Betsy James.

Andrew met Betsy, whose family summered in Maine not far from the Wyeths, in 1939, and he proposed to her when they had known each other for only a week. They married in May 1940; Andrew was 22, Betsy, 18. Although not an artist herself, Betsy had grown up in a household preoccupied with art and design. Beautiful, sensitive, unconventional, intuitive and highly intelligent, she not only managed household affairs and raised their two sons—Nicholas, now an art dealer, and James (Jamie), a much-exhibited painter and watercolorist—but she also became Andrew’s protector, his model and his principal artistic guide, taking over the role his father had performed so assiduously.

Even when sales were slow, she insisted that her husband turn down commercial illustration projects and focus on painting. Betsy “made me into a painter that I would not have been otherwise,” Wyeth told Meryman. “She didn’t paint the pictures. She didn’t get the ideas. But she made me see more clearly what I wanted. She’s a terrific taskmaster. Sharp. A genius in this kind of thing. Jesus, I had a severe training with my father, but I had a more severe training with Betsy....Betsy galvanized me at the time I needed it.”

Andrew needed Betsy’s support, for his father did not approve of his subdued, painstaking temperas. “Can’t you add some color to it?” NC asked about one of them. He was particularly disparaging about Andrew’s 1942 tempera of three buzzards soaring over Chadds Ford. “Andy, that doesn’t work,” he said. “That’s not a painting.” Discouraged, Andrew put the painting in his basement, where his sons used it to support a model train set. Only years later, at the insistence of his friend, dance impresario Lincoln Kirstein, did he return to it. He finished the work, titled Soaring, in 1950; it was exhibited at Robert Macbeth’s gallery that same year.

By 1945, NC—then 63 and shaken by World War II and what he called “the lurid threads of the world’s dementia”—was losing confidence in himself as a painter. He became moody and depressed. Brightening his colors and flirting with different styles didn’t seem to help. He became more and more dependent on Andrew, relying on him for encouragement and support.

On the morning of October 19, 1945, NC was on an outing with his namesake, 3-year-old Newell Convers Wyeth, the child of his oldest son, Nathaniel. At a railroad crossing by the farm of a neighbor, Karl Kuerner, the car NC was driving stopped while straddling the tracks—no one knows why. A mail train from Philadelphia plowed into it, killing NC instantly and hurling little Newell onto the cinder embankment. He died of a broken neck.

After that, Andrew’s work became deeper, more serious, more intense. “It gave me a reason to paint, an emotional reason,” he has said. “I think it made me.” One day, walking close to the tracks where his father was killed, he spotted Allan Lynch, a local boy, running down the hill facing the Kuerner farm. Wyeth joined him. The two found an old baby carriage, climbed into it together, and rolled down the hill, both of them laughing hysterically. The incident inspired Wyeth’s 1946 painting Winter, which depicts Lynch running down the hill, chased by his shadow. “The boy was me at a loss, really,” he told Meryman. “His hand, drifting in the air, was my hand, groping, my free soul.”

In the painting, the hill is rendered with tiny, meticulous, but also strangely unpredictable, strokes, anticipating the hill that Wyeth would portray two years later in Christina’s World. In Winter, Wyeth has said, the hill became the body of his father. He could almost feel it breathe.

In 1950, two years after he painted Christina’s World, Wyeth was diagnosed with bronchiectasis, a potentially fatal disease of the bronchial tubes. Most of a lung had to be removed. During the operation, Wyeth’s heart began to fail, and he later reported having had a vision in which he saw one of his artistic heroes, the 15th-century painter Albrecht Dürer, walk toward him with his hand extended, as if summoning him. In his vision, Wyeth started toward his hero, and then pulled back as Dürer withdrew.

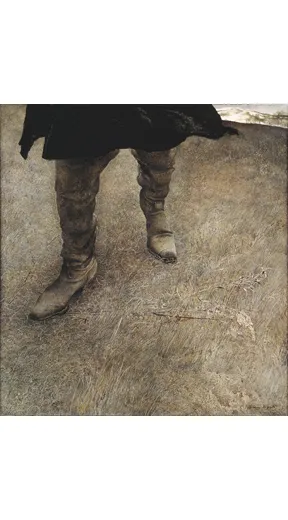

The operation severed the muscles in Wyeth’s shoulder, and although he eventually recovered, it was unclear for a time whether he would paint again. During weeks of recuperation, he took long walks through the winter fields, wearing a pair of old boots that had once belonged to artist Howard Pyle, his father’s teacher and mentor.

Trodden Weed, which Wyeth painted several weeks after the surgery—his hand supported by a sling suspended from the ceiling—depicts a pair of French cavalier boots in full stride across a landscape. The painting is both a kind of self-portrait and a meditation on the precariousness of life. Wyeth has said that the painting reflects a collection of highly personal feelings and memories—of the charismatic Pyle, whose work greatly influenced both Wyeth and his father, of Wyeth’s childhood, when he dressed up as characters from NC’s and Pyle’s illustrations, and of the vision of death as it appeared to him in the figure of Dürer, striding confidently across the landscape.

By the time of his rehabilitation, Wyeth had achieved a signature look and a distinctive personal approach, finding nearly all of his subjects within a mile or so of the two towns in which he lived—Chadds Ford, where he still spends winters, and Cushing, Maine, where he goes in the summer. “I paint the things I know best,” he has said. Many of his most memorable paintings of the 1960s and ’70s, in fact, focus on just two subjects—the Kuerner farm in Chadds Ford (owned by German immigrant Karl Kuerner and his mentally unbalanced wife, Anna) and the Olson house in Cushing, inhabited by crippled Christina and her brother, Alvaro.

During the 1940s and ’50s, Wyeth was encouraged by two notable supporters of the avant-garde, Alfred Barr, the founding director of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, who purchased, and promoted, Christina’s World, and painter and art critic Elaine de Kooning, the wife of renowned Abstract Expressionist Willem de Kooning.

In 1950, writing in ARTnews, Elaine de Kooning praised Wyeth as a “master of the magic-realist technique.” Without “tricks of technique, sentiment or obvious symbolism,” she wrote, “Wyeth, through his use of perspective, can make a prosperous farmhouse kitchen, or a rolling pasture as bleak and haunting as a train whistle in the night.” That same year, Wyeth was lauded, along with Jackson Pollock, in Time and ARTnews, as one of the greatest American artists. But as the battle lines between realism and abstraction were drawn more rigidly in the mid-1960s, he was increasingly castigated as old-fashioned, rural, reactionary and sentimental. The 1965 ordination of Wyeth by Life magazine as “America’s preeminent artist” made him an even larger target. “The writers who were defending abstraction,” says the Philadelphia Museum’s Kathleen Foster, “needed someone to attack.” Envy may also have played a part. In 1959 Wyeth sold his painting Groundhog Day to the Philadelphia Museum for $31,000, the largest sum that a museum had ever paid for a work by a living American painter; three years later he set another record when he sold That Gentleman to the Dallas Museum of Art for $58,000.

Throughout the 1970s and ’80s, Wyeth kept up a steady stream of major paintings—landscapes of fir trees and glacial boulders, studies of an 18th-century mill in Chadds Ford and, above all, likenesses of people he knew well, such as his longtime friend Maine fisherman Walt Anderson and his Pennsylvania neighbors Jimmy and Johnny Lynch.

Then, in 1986, Wyeth revealed the existence of 246 sketches, studies, drawings and paintings (many of them sensuous nudes) of his married neighbor, Helga Testorf, who was 22 years his junior. He also let it be known that he had been working on the paintings for 15 years, apparently unbeknown even to his wife. (For her part, Betsy didn’t seem entirely surprised. “He doesn’t pry in my life and I don’t pry in his,” she said at the time.) The revelation—many found it hard to believe that the artist could have produced so many portraits without his wife’s knowledge—thrust the works onto the covers of both Time and Newsweek. The story’s hold on the popular imagination, wrote Richard Corliss in Time, “proved that Wyeth is still the one artist whose style and personality can tantalize America.” An exhibition of the works at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. followed ten months later. But the revelation was also seen as a hoax and publicity stunt. In his 1997 book American Visions, for example, Time art critic Robert Hughes denounced the way the Helga pictures came to light as a “masterpiece of art-world hype.”

This past April, NBC News’ Jamie Gangel asked Wyeth why he had kept the paintings secret. “Because I’d been painting houses, barns, and, all of a sudden, I saw this girl, and I said, ‘My God, if I can get her to pose, she personifies everything I feel, and that’s it. I’m not going to tell anyone about this, I’m going to just paint it.’ People said, ‘Well, you’re having sex.’ Like hell I was. I was painting. And it took all my energy to paint.” Wyeth went on to say that he still paints Helga once in a while. “She’s in my studio in and out. Sort of an apparition.”

In any case, many in the New York art world seized upon the Helga paintings as confirmation of their belief that Wyeth was more cultural phenomenon than serious artist. Even today, when realism has come back in vogue, hostility to Wyeth’s work remains unusually personal. Former MoMA curator Robert Storr said in the October 2005 issue of ARTnews that Wyeth’s art is “a very contrived version of what is true about simple Americans....I was born in Maine. I know these people and I know. Nothing about Wyeth is honest. He always goes back to that manicured desolation....He’s so averse to color, to allowing real air—the breath of nature—into his pictures.” In the same article, art critic Dave Hickey called Wyeth’s work “dead as a board.” Defenders are hard put to explain the virulence of the anti-Wyeth attacks. “The criticism doesn’t engage with the work at all,” says curator Knutson. “It is not persuasive.”

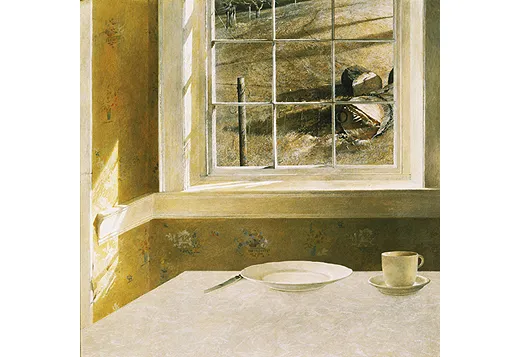

The current exhibition, she says, has tried to probe into Wyeth’s creative process by looking at the way he has handled recurrent themes over time. She notes that he tends to paint three subjects: still-life vignettes, vessels (such as empty buckets and baskets), and thresholds (views through windows and mysterious half-opened doors). All three, she says, serve Wyeth as metaphors for the fragility of life. In Wyeth’s paintings, she adds, “you always have the sense that there is something deeper going on. The paintings resonate with his highly personal symbolism.”

The artist’s brother-in-law, painter Peter Hurd, Knutson writes, once observed that NC Wyeth taught his students “to equate [themselves] with the object, become the very object itself.” Andrew Wyeth, she explains, “sometimes identifies with or even embodies the objects or figures he portrays.” His subjects “give shape to his own desires, fantasies, longings, tragedies and triumphs.” In a similar way, objects in Wyeth’s work often stand in for their owners. A gun or a rack of caribou antlers evokes Karl Kuerner; an abandoned boat is meant to represent Wyeth’s Maine neighbor, fisherman Henry Teel. Studies for Wyeth’s 1976 portrait of his friend Walt Anderson, titled The Duel, include renderings of the man himself. But the final painting contains only a boulder and two oars from Walt’s boat. “I think it’s what you take out of a picture that counts,” the artist says. “There’s a residue. An invisible shadow.”

Wyeth also says that “intensity—painting emotion into objects,” is what he cares about most. His 1959 painting Groundhog Day, for instance, appears to portray a cozy country kitchen. Only gradually does the viewer become aware that there’s something off, something uncomfortable, strangely surreal, about the painting. The only cutlery on the table is a knife. Outside the window, a barbed-wire fence and jagged log wrapped in a chain dominate the landscape. As Kathleen Foster notes in her catalog essay, the painting adds up to a portrait of Wyeth’s neighbor, the volatile, gun-loving Karl Kuerner, and his troubled wife, Anna. Far from cozy, the painting suggests the violence and even madness that often simmers beneath the surface of daily life.

While seemingly “real,” many of Wyeth’s people, places and objects are actually complex composites. In Christina’s World, for example, only Olson’s hands and arms are represented. The body is Betsy’s, the hair belongs to one of the artist’s aunts, and Christina’s shoe is one he found in an abandoned house. And while Wyeth is sometimes praised—and criticized—for painting every blade of grass, the grass of Christina’s World disappears, upon examination, in a welter of expressive, abstract brushstrokes. “That field is closer to Jackson Pollock than most people would like to admit,” says Princeton professor John Wilmerding, who wrote the introduction to the exhibition catalog.

Wyeth “puts things in a mental blender and comes out with something unique,” says Chris Crosman, who worked closely with the Wyeths when he was director of the Farnsworth Museum in Maine. “A lot of it is based on what he sees around him, but when he gets down to painting he combines different places and perspectives. His paintings are as individual and personal as any artworks that have ever been created.”

Artist Mark Rothko, renowned for his luminous abstract canvases, once said that Wyeth’s work is “about the pursuit of strangeness.” As Wyeth has aged, his art has grown only stranger, as well as more surreal and personal. Breakup (1994) depicts the artist’s hands springing from a block of ice; Omen (1997) pictures a naked woman running across a barren landscape while a comet streaks across the sky. And one of Wyeth’s most blackly humorous paintings, Snow Hill (1989), depicts several of his favorite models, including Karl and Anna Kuerner and Helga Testorf, dancing around a maypole, celebrating the artist’s death.

“It’s a shock for me to go through and see all those years of painting my life,” Wyeth says of the current show. “When I made these paintings, I was lost in trying to capture these moments and emotions that were taking place. It’s a very difficult thing for an artist to look back at his work. If it’s personal, it touches all these emotions.”

Should we consider Wyeth old-fashioned or modern? Perhaps a little of both. While he retains recognizable imagery, and while his work echoes great American realists of the 19th-century, such as Thomas Eakins and Winslow Homer, the bold compositions of his paintings, his richly textured brushwork, his somber palette and dark, even anguished spirit, suggest the work of the Abstract Expressionists.

One of the goals of this exhibition, says Kathleen Foster, “has been to put Wyeth back into the context of the 20th century, so people can see him as a contemporary of the Surrealists, and a colleague of the Abstract Expressionists—artists whose work he admires and feels kinship with....People have pigeonholed Wyeth as a realist, a virtuoso draftsman, almost like a camera recording his world, and we want to demonstrate that realism is only the beginning of his method, which is so much more fantastic and artful and memory-based than people may have realized. And strange.” And what does Wyeth think of his place in the contemporary art world? “I think there is a sea change,” he says. “I really do. It’s subtle, but it’s happening. Lincoln Kirstein wrote me several times saying: ‘You just keep on. You’re way ahead.’ I like to think that I’m so far behind that I’m ahead.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/henry-adams-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/henry-adams-240.jpg)