X-Ray Art: A Deeper Look at Everyday Objects

Brit Hugh Turvey adds his artistic touch to x-rays of suitcases, old shirts and a host of other subjects

Hugh Turvey calls one of his earliest images Femme Fatale. Using an x-ray, he scanned his wife’s foot in a dangerously high stiletto.

“I think we all understand that your foot is going through quite a lot when it is in a stiletto, but to actually physically see it and to see the angle of the bones,” says the British artist. He completes his thought, I imagine, with a shiver. “Not only do you have this distorted foot, but you have these small nails that were in the actual construction of the shoe. It just looked like a torture device.”

That was about 20 years ago.

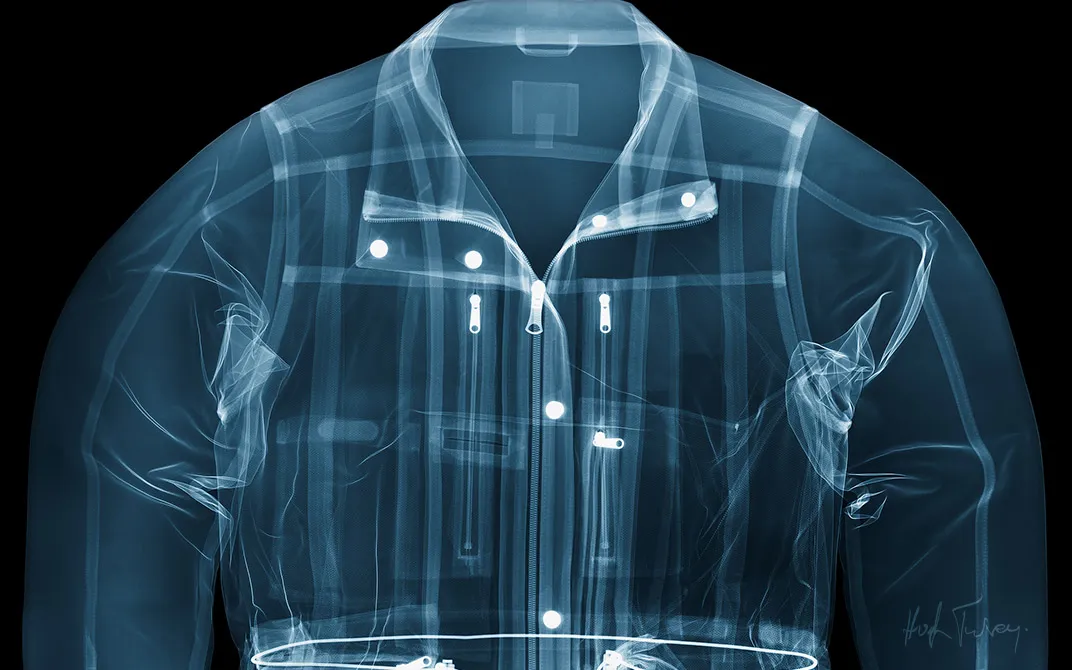

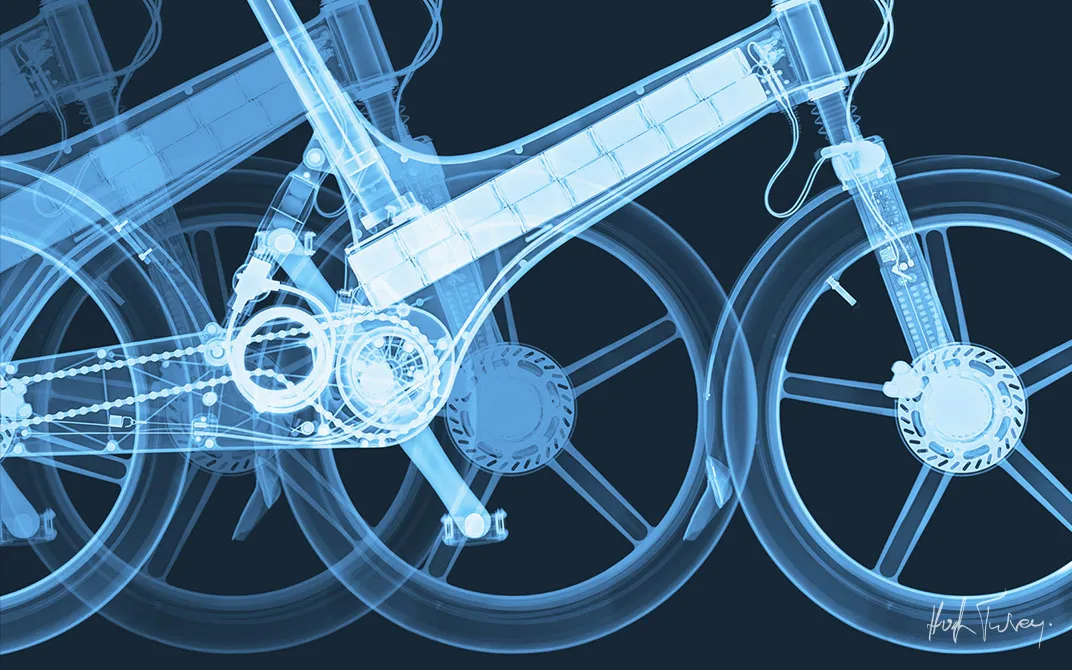

Since then, Turvey has walked the line between photography and radiology, creating art using x-ray equipment from the medical and security industries. He has coined the term “xogram” to describe his medium, a mash-up between an x-ray and a photogram, made by placing an object on light-sensitive paper.

For a while, the artist obsessed over flowers. It was challenging to use x-ray to bring out the internal structure of something as thin as a petal, and he invested a lot of time in perfecting his technique. One by one, he’d scan dahlias, calla lilies, gerbera daisies and thistles. Later on, he captured a series of eggs that shows a chick’s development from yolk and white to ready-to-hatch egg in 21 days. And, then there was the elephant skull. “It is a strange looking item when it doesn’t have its flesh on it,” he says.

Turvey has produced compelling xograms of a wide range of objects: wrapped presents, suitcases, motorcycles and musical instruments. “You tend to start viewing everything from a density point of view,” he says. “I view most of the world around me in terms of how I imagine it is internally and how it would look if we were to try and x-ray it.” Smithsonian commissioned Turvey to shoot the cover of its May 2012 travel issue (see it here). And, recently, he turned to portraits—x-ray portrayals of people’s most precious possessions. “By ‘exposing’ these objects in x-ray, I ‘expose’ the owner,” he says.

Of course, Turvey isn’t just taking x-rays of his subjects; he always adds his artistic touch. To achieve the level of detail he desires, enough to convey the subject to the viewer as quickly as possible, he sometimes layers photographs onto the x-ray. Turvey also enhances the images with color. “X-ray is a gray scale process, and color is an amazing tool to control where the viewer looks and in what order over an object,” he says. “It actually puts the depth back into the image in quite a lot of cases.”

Since 2009, Turvey has been an artist-in-residence at the British Institute of Radiology. In this role, he aims to help create better healthcare environments and to improve the patient experience. His artistic interpretations of x-ray are used as educational tools. “It helps patients understand the process that they are going to go through when they see everyday objects x-rayed,” Turvey explains.

“When you are a child, and you’re seeing things for the first time, everything is exciting. As you go on, maybe that excitement gets lost and you just take things for granted,” says Turvey. Ultimately, he wants viewers of his images to see the world with fresh eyes. To help, he has started to adhere large vinyls of his images onto glass partitions in offices and hospitals.

“Beauty isn’t skin deep. The world is so much more complicated than it appears,” says the artist. “When you are able to see just a little bit deeper, I think you become a better person.”

About 70 of Turvey’s images, spanning his career, will be on display in “X-POSÉ: Material and Surface,” an exhibition at gallery@oxo at Oxo Tower Wharf in London’s South Bank from February 12 to February 23, 2014.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c0/3e/c03e8e6c-f876-4a4f-8cc2-8fbac91ac355/hughturvey_655_london_oxo_exhibition_2014_smithsonian_0007_layer_comp_8.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a8/44/a844eba9-95f9-46c0-89c6-7653f0cf46f2/hughturvey_655_london_oxo_exhibition_2014_smithsonian_0005_layer_comp_6.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)