How a Photograph Solved an Art Mystery

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/AAA_tannhenr_5879_SIV.jpg)

Born in Pittsburgh and raised in Philadelphia, African-American artist Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859–1937) spent his mature career in France, where he won great fame for paintings based on religious subjects. Tanner had left the United States in 1891 to escape racial prejudice and find artistic opportunity. From the 1890s until his death, Tanner’s allegiances remained divided between his adopted home in France and his origins in the United States. In a series of biblically-themed paintings produced across his four decades in Europe, Tanner repeatedly acknowledged this experience of being a sojourner abroad, separated from his birthplace.

A discovery I recently made in the Tanner papers at the Archives of American Art provides new information about two of the artist’s paintings—one of them long thought to be lost, and the other under-studied and little-understood. This revelation also enriches our understanding of Tanner’s conflicted relationship with America, suggesting how the artist might have come to terms with his expatriate identity.

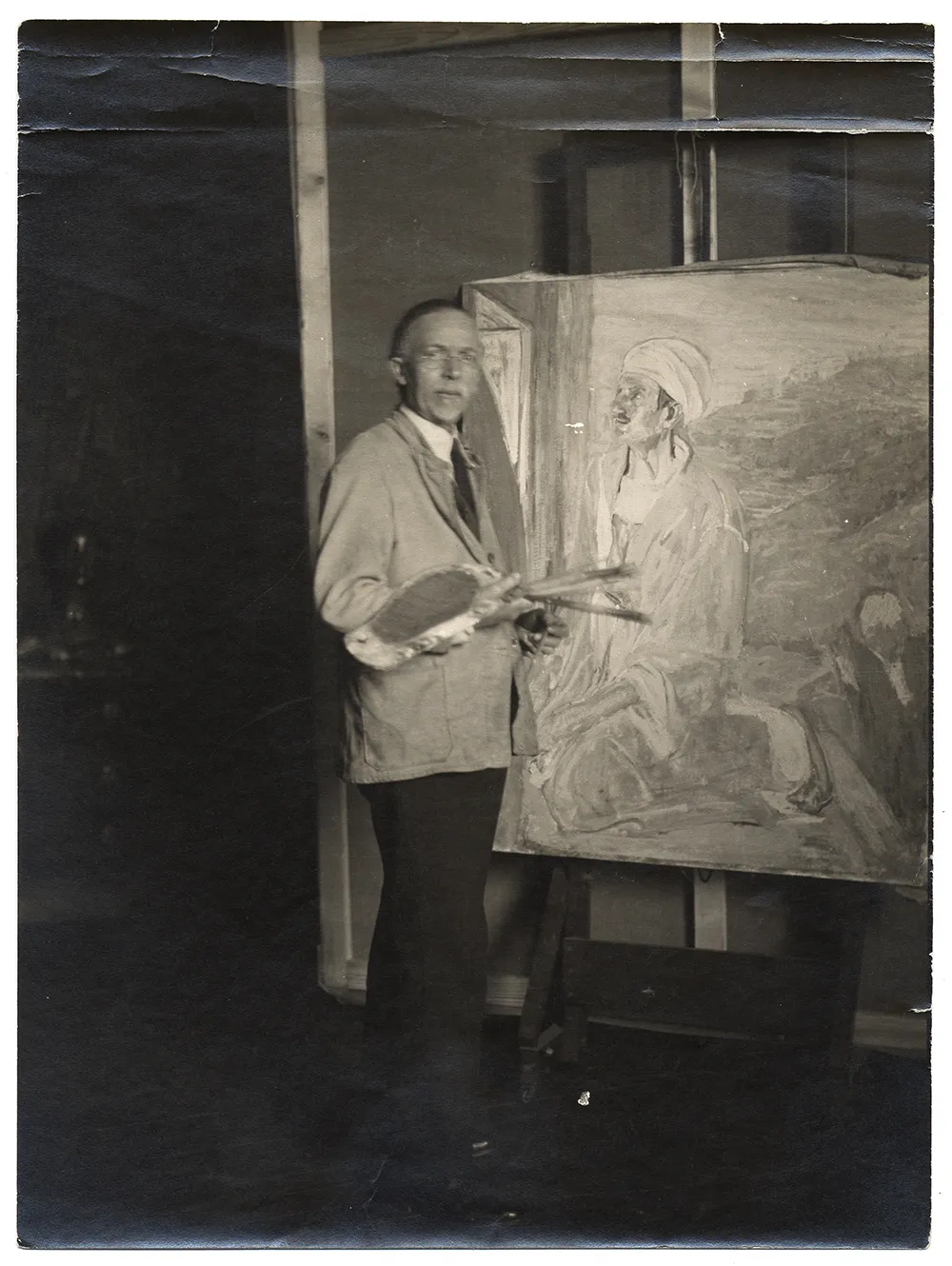

In an undated photograph in the artist’s papers, Tanner stands in his Paris studio with paintbrushes and palette in hand. Resting on the easel behind him is an oil painting of Judas, the disciple who betrayed Jesus. The painting, which likely dates from the early 1920s, has been thought to have survived only in the form of this single archival image.

Tanner had endeavored to portray Christ’s disloyal disciple once before. In his circa 1905 painting Judas Covenanting with the High Priests, the artist showed Judas in the conventional manner, receiving the thirty pieces of silver from the Jewish religious leaders at Jerusalem in exchange for his help identifying Jesus to them. Tanner exhibited this earlier version at the Carnegie International Exhibition in 1905 and the Carnegie Institute purchased the painting for its collection the following year, but it was later deaccessioned and remains unlocated.

Tanner’s circa 1920s rendition of Judas, on the other hand, is much more unusual, showing the betrayer kneeling before an open doorway in a pose of supplication typically associated with the return of the Prodigal Son. In Mutual Reflections: Jews and Blacks in American Art, Milly Heyd offers perhaps the only art historical interpretation of this lost painting: “Could this concept [of a penitent Judas] refer to his [Tanner’s] personal involvement with the theme, his sense that by living in Paris he had betrayed his people, his repentance, and his continued hesitation leading to his dissatisfaction with the portrayed image and its destruction?” Judas’ idiosyncratic appearance, as Heyd argues, represents Tanner’s attempt to engage with his own experiences of wandering and exile as well as his longing to return homeward and find acceptance.

Conflating the identity of the betrayer with the contrite posture of the Prodigal Son in this painting, Tanner perhaps saw his life in Europe as another kind of betrayal—an abandonment of his homeland. That Tanner hired a professional photographer to capture him alongside Judas suggests his desire to identify with the figure in this way and to seek repentance.

In such an interpretation, Tanner’s motivations for producing the painting and documenting it in a photograph are also inseparable from his eventual dissatisfaction with the picture. After all, his ambivalence toward his own expatriatism—resigned as he was to his lifelong exile from America—finds its fulfillment in his ensuing discontent with a painting of penitent homecoming and his decision to obliterate it. Except there is no archival or material evidence to corroborate the painting’s total destruction. Heyd’s argument about the subsequent fate of Judas is based solely on an article about Tanner published in the Baltimore Afro-American on January 30, 1937, which declared that the artist “destroyed” the picture “after completion.”

In fact, another painting by Tanner, Two Disciples at the Tomb (The Kneeling Disciple) (hereafter Two Disciples), provides an answer to what ultimately happened to Tanner’s unlocated canvas and also offers closure to Tanner’s conflicted rendering in Judas of a recalcitrant yet repentant disciple. In his Two Disciples from around 1925—which significantly revises his circa 1906 version of the same subject, The Two Disciples at the Tomb—Tanner shows the moment in John 20:4–6 when the Apostle John stoops down and looks into the tomb where Christ had been buried, yet finds it empty. Peter, who had been following John, stands in the shadows of Tanner’s canvas a few steps away.

To achieve this new rendition of a familiar scene, Tanner completed several charcoal study drawings from a model, where he worked out the pose of the painting’s central figure and carefully captured the mottled effects of light and shadow across his face. The finished canvas appeared at the Thirty-ninth Annual Exhibition of American Paintings and Sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago in October 1926. Critics like Karen Fish, in her review of the exhibition published in The American Magazine of Art later that year, highlighted its differences from the artist’s 1906 rendition—the blue-green tones and physical remoteness of Tanner’s revised version were a significant departure from the yellow-tinged interior scene of his earlier composition—while also acknowledging what the two paintings shared: “the reverence, the mystery, and the faith which breathes in all of Mr. Tanner’s works.”

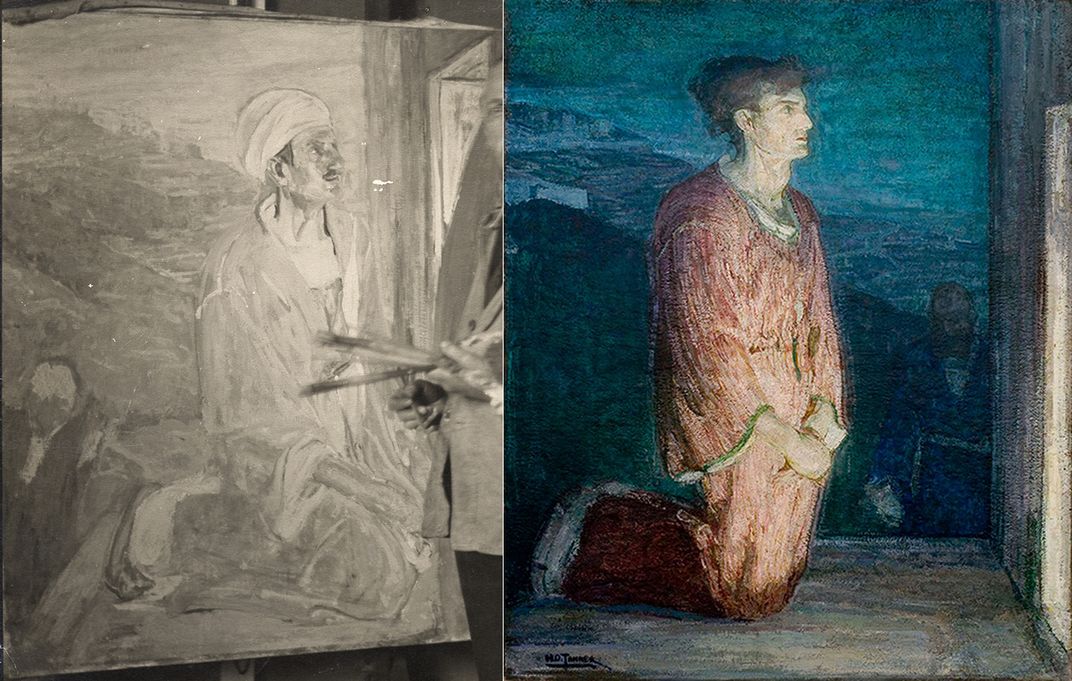

In Two Disciples, as in Judas, a male figure, bathed in light, kneels on a shallow ledge before an open doorway. Again, like Judas, behind the central figure the ridges of two terraced hillsides in the distance peak at the walled city of Jerusalem. In the past, scholars have described the solid paint and heavy brushstrokes that carve out a series of fluted folds in John’s robe as indicative of the figure’s monumentality and importance in the scene, when “the disciple whom Jesus loved” bowed before Christ’s newly empty tomb.

The thick impasto of John’s garment is so heavily constructed, however, that these dense layers of pigment suggest Tanner was attempting to build up a new figure on top of an old composition. And, indeed, in raking light—and even in published photographs of the Two Disciples—several ghost-like forms under the surface of the picture come into view: a turbaned head just to the right of John’s head; a bent knee on the ground; and the vertical line marking the original corner of the building before which Judas has knelt.

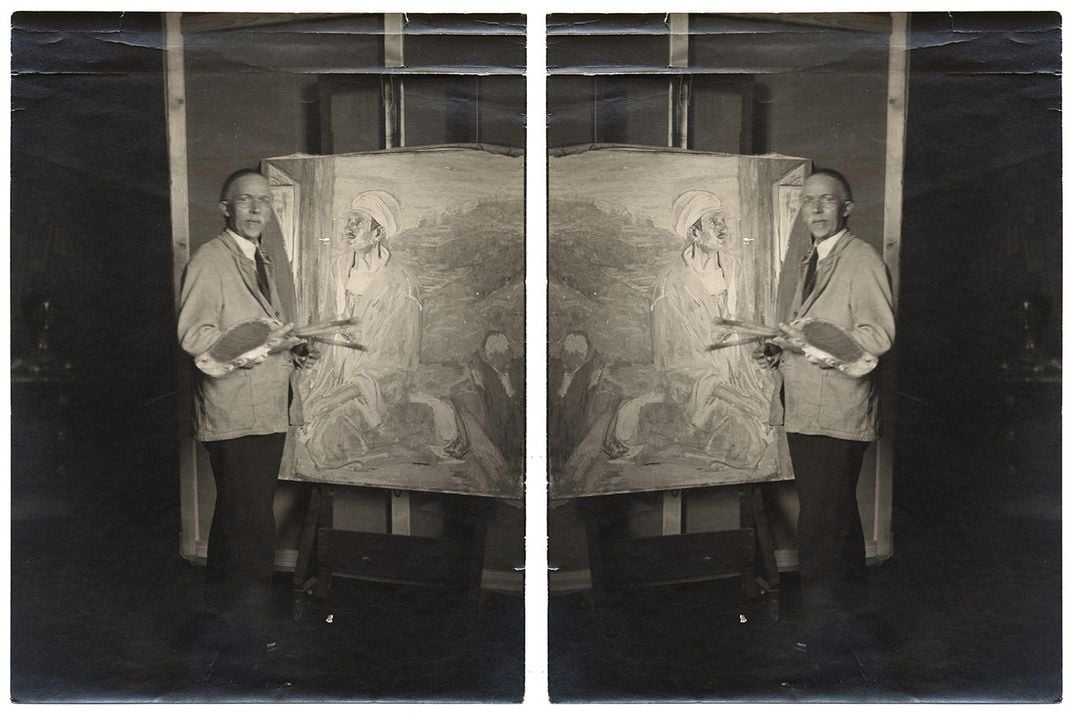

These pentimenti suggest that Tanner painted his new scene of the Two Disciples over his circa 1920s painting of Judas, long thought to be lost. The connection between these two paintings has likely gone unnoticed until now because the photograph showing Tanner beside Judas in the Archives of American Art was apparently printed in reverse. In the original orientation of the print by the Parisian photography studio of L. Matthes, Tanner appears left-handed, with his palette and bundle of brushes in his right hand and a single brush held up to the canvas in his left; however, we know from other archival photographs that Tanner was, in fact, right-handed. In addition, the Matthes photograph incorrectly shows the buttons on the left side of Tanner’s jacket, even though period fashion dictated (and other photographs of Tanner confirm) that buttons appear on the proper right side of a man’s coat.

When the orientation of the photograph is corrected accordingly, the shared structure of Judas and the Two Disciples becomes readily apparent. The ground plane in the foreground, the topography and architectural features of the hillside in the background, and the doorway and exterior wall of the tomb at right are all nearly identical in both paintings. Moreover, when seen alongside one another, the spectral traces of Judas’s head and knees emerge in the center and right foreground of the Two Disciples.

Rather than destroying Judas, as earlier authors assumed, it is more likely that, after abandoning this earlier picture, he reused the canvas for the Two Disciples. Tanner frequently recycled or repurposed canvases throughout his career. For example, following the disastrous reception of his La Musique at the 1902 Paris Salon, Tanner covered that failed painting with The Pilgrims of Emmaus, which received a major prize at the Salon three years later and was purchased by the French government.

With the Two Disciples, then, Tanner converted a penitent picture of betrayal in the original composition into an epiphanic scene of belief. Soon after the moment in Tanner’s picture, John entered the tomb, “and he saw, and believed” (John 20:8). The palimpsest of the painting—the guise of a betrayer transformed and transposed into the image of a believer—reflects, then, the ongoing tension within Tanner’s understanding of his place in the world. Beneath the surface of Tanner, the confident apostle of the expatriate artistic community, always lingered another guise: Tanner, the remorseful American disciple who forever remained conflicted about his rejection and abandonment of his homeland across the ocean. And yet the expatriate artist maintained his affection for the country of his birth. As he wrote to critic Eunice Tietjens in 1914, “[S]till deep down in my heart I love [America], and am sometimes very sad that I cannot live where my heart is.”

This post originally appeared on the Archives of American Art Blog.