NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN

How to Play Snow Snake, the Traditional Winter Game of the Haudenosaunee

This age-old game uses the techniques of skill and strength to propel a wooden pole down a long snow track

:focal(500x376:501x377)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/44/b3/44b397fa-2f9b-445b-ba2e-676f3e83e454/snow_snake_game_painting.webp)

Winter is a special season for the Haudenosaunee as it is a time to revisit an age-old tradition – the game of snow snake. The Haudenosaunee hoʊdinoʊˈʃoʊniː/ or "People of the Longhouse" are also known as The Iroquois /ˈɪrəkwɔɪ/ or /ˈɪrəkwɑː/ and reside in northeastern United States and Southeast Canada. They are comprised of six nations: Seneca, Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga and Tuscarora. Within the Haudenosaunee, approximately 30 snow snake teams represent different communities within each tribe.

According to Haudenosaunee oral tradition, the game of snow snake was called a medicine game and has been played for hundreds of years. From its inception, the game was played exclusively by men as a ceremonial winter game. It was originally a form of communication between villages also intended to build ties between the players. The throwing of "snow snakes" through a trough of snow developed into a competitive sport during long winters when the long track was not used for communication. In the 1950s snow snake almost died out, but slowly the sport was revived and regained popularity. Today, tournaments are held in Haudenosaunee communities each weekend during the snow season, usually over a two-day period.

It is a winter past time for the men old and young to come together, share stories, and what went on in the community that year, a lot of hard work, time, and pride as in anything we do as Ongweh (Original) people. - JR Dowdy (Cattaraugus Seneca)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/91/72/91724b92-d6f7-458e-b91e-46d629f6d20f/snow_snake_2.jpeg)

The name "snow snake" is said to have come from the snakelike wiggling motion of the poles as they slide down the icy track. Another reason for playing the game is to hone hunting skills such as spear-throwing. Snow snakes are wooden poles that are carved and weighted to slide easily over snow and ice. The poles are made of hardwoods such as maple, hickory, mahogany, ember, iron wood, and juneberry. There are often different snow snakes for playing in different conditions, such as powdery snow, packed snow, or icy snow. Many players customize their snow snakes, decorating them with colorful designs, or adding minor modifications such as a lead front tip. Men called “doctors” usually wax the wooden surface, much like wax is used for skis.

Snow snake is a test of both skill and strength. The object of the game is to throw the snow snake the farthest distance along a smooth track with a gully, made in the snow. Wherever the snow snake stops, a marker is placed to signify the farthest point reached. The individual player who throws the stick the farthest wins. In team competition, team’s alternate tosses. A team of all-male competitors is known as a “corner.” There is a predetermined number of rounds during which each team is allowed four throws per round. The stick thrown the farthest in each round receives one point. When a team scores four points, “game out” occurs and that team wins the game.

This game is centuries old. At one time a one-foot snow snake was used and played at night by lantern in big circle. - Sheldon Sundown (Cattaraugus Seneca)

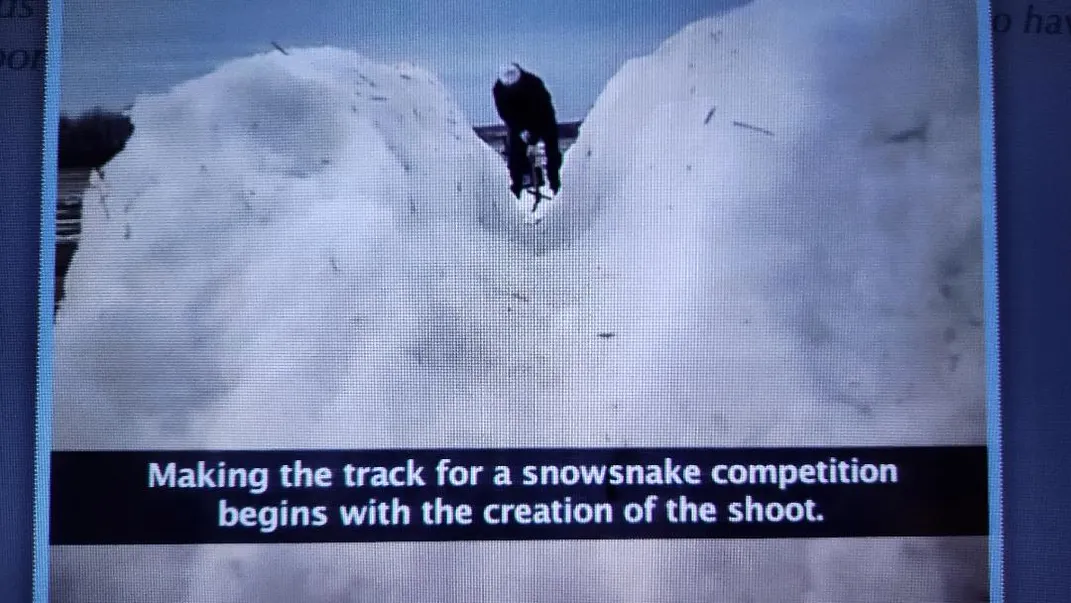

Making the snow snake competition track begins with the creation of the throwing area called a “shoot.” Shoots and are typically five inches deep, extending for a mile or more. To create a crevasse for the snow snakes to travel down, heavy logs are pulled in the center of the track. Hand tools are used to even out the crevasse for the snow snake to glide over.

Tournaments are divided into two categories called “mudcat” and “long stick” divisions. Mudcat refers to shorter snow snake sticks, usually 2 ½ to 3 feet long. Long sticks are approximately 6 feet long. Youth compete in tournaments featuring players as young as 6 years old, to teens. After the youth competitions have concluded, the adult tournament takes place. Adult throwers compete in the class that they rank, called a “rate”, with first rate being the best, then second rate, and the third rate for amateur players. Adults who use mudcats have only one class because they are ranked highest in that division. Individuals start off as a 3 rate, then a 2 rate, and then a 1 rate. Once a competitor has achieved a 1 rate, they can never go back to being a 2 or 3 rate.

The Haudenosaunee version of snow snake originally began as a male medicine game, where women were not allowed to play or touch a man’s playing stick, similar to lacrosse. In some cases women are not even allowed to observe the game being played. In parity, Haudenosaunee women also have their own exclusive ceremonies and events which men are not allowed to attend. Snow snake was also played by other tribes including the Dakota, Anishinaabe, Cree, Northern Cheyenne, Lenape, HoChunk, Wyandotte, Otoe, Penobscot, Sauk, Meskwaki, and Omaha.

Today, snow snake is played mostly for sport, prestige, and to build tribal ties. This medicine game of skill continues to be great for socializing, feasting, sharing stories, and carrying on ancestral traditions.