SMITHSONIAN CENTER FOR FOLKLIFE & CULTURAL HERITAGE

How Living Heritage Heals the Invisible Fractures of the Soul in Eastern Türkiye

On February 6, 2023, a 7.8 magnitude earthquake fractured the lives of over 13.5 million people across ten eastern provinces in my home country.

:focal(600x400:601x401)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/33/da/33da16fc-dc74-478e-8e3c-960bcb0b68cc/antakya-we-will-come-back-graffiti.jpg)

On February 6, 2023, a 7.8 magnitude earthquake fractured the lives of over 13.5 million people across ten eastern provinces in my home country, Türkiye. The earthquake and its aftershocks claimed the lives of over 50,000 people and injured more than 100,000. Over 7,000 buildings were destroyed, and sixteen times that severely damaged.

Unearthing what is lost but not forgotten: Antakya, Hatay Province

Five months later, I visited the city of Antakya, the site of much of the destruction. Even then, the air reeked with an unfamiliar putridity—what I later learned was the odor of decaying bodies left under the scorching July heat. I had driven 480 miles from my hometown in Antalya to write about the condition of heritage sites, but that seemed less of a priority now.

Government contractors combed through the rubble, salvaging the metal framing of demolished buildings and leaving behind the belongings of uprooted families. Initially, I tried not to look too closely, even through my camera. I felt guilty being there, prying into a tragedy that was not mine. Maybe not looking closely would make it easier for me to walk away.

Soon, all will be carried to a designated dumping ground. What will fill the void left by people? I asked myself, fearful of the answer. What will happen to the buried stories, memories, and rituals of the diverse peoples who make Antakya what it is as much as the Habib-i Neccar Mosque or the Church of St. Pierre?

My fear overcame my guilt, and I looked beneath.

The excavators dug through the rubble, unearthing evidence of lives I will never know. Through the shattered wall of a kitchen, I spotted a jar of homemade olives pickled for the breakfast table, in the same way my grandmother pickles olives for my family. Countless garlic bunches hung on half-ruined balconies, waiting for a never-cooked meal. There is a bookbag, probably belonging to a kid the same age as my little cousin.

Spray-painted signs were scattered across the city, written across soon-to-be-demolished buildings: “We will come back, Hatay.” “We haven’t left you.” “We will heal you, don’t lose hope.” Each stamped phrase completed the one before, merging into a single, harmonious verse. I was reading a love letter written to the motherland.

I followed the verses and ended up in an alley called Zambak Road, adjacent to historic Kurtulus Street. Five years prior, I had visited Antakya with my family and stepped foot on streets I now struggled to recognize.

As I tried to find a way out, I heard a distant voice warning me, “I heard the rubble move. Don’t go further down the street.”

The woman made her way toward me. “I am Hilal. When I heard that my childhood home was gone, I came to see it with my own eyes.” Her face was hidden behind a surgical mask she hoped would prevent her from inhaling the asbestos from demolished buildings. “My husband developed asthma after the earthquake and can’t go outside.” She, too, was wandering alone.

Born and raised in Antakya, Hilal is of Arab descent and is part of the Alevi community, a minority among Shia Muslims. Despite the state of our surroundings, she was among those who refused to leave.

As we moved past empty homes, some collapsed and others awaiting demolition, she told me the story of her childhood street. She pointed to the remains of a traditional stone home with marble ornaments and cracked windows. “My Christian neighbor Victoria lived there! I used to visit her for coffee.” We walked across the narrow path, pivoting around heaps of rubble, and jumped over a short tomato vine growing out of the brick, finding life in the most desolate place.

The mechanical hum of excavators echoed in a street that was once filled with joyous chatter in Arabic, Turkish, and Armenian. Even before the earthquake, many of Hilal’s Alevi Shia Muslim, Christian, and Jewish neighbors had migrated away because of ethnic tensions and geopolitical hardships. To stay was to resist erasure. Now, her street’s rich cultural and religious diversity was evident only in the remains of a mosque, synagogue, and church.

As we moved past a collapsed home, Hilal pointed in excitement. “People used to line up by the wall to get their fortune read by Auntie Nahiye.” Just a few steps down the street, she caressed the chipped paint of an old brick home. “My uncle had a tailor’s shop here. I learned to sew in this building.”

In the absence of a traditional roadmap, I was left to navigate the lifescape of the city through the memories of those who called it home—who still love it dearly.

Since the earthquake, I had seen countless bird’s-eye-view photos displaying heaps of ruins in a hopeless grayish hue. Up close, another story emerged, and the nauseating gray broke into every shade of hope life offers. I came to Eastern Türkiye to report on the condition of cultural heritage sites but left with a story about the people who are the living vessels of the culture. Despite the desolate conditions, life resumes in the margins as people find ways to reground themselves in their ancestral land by tending to their roots and healing as a community.

First sips of hope: Antakya, Hatay Province

As I parted ways with Hilal to make my way sixty miles north to Iskenderun, I saw a cigarette and coffee stand near the street where I had parked my car. I approached with curiosity. Coffee is a luxury I did not anticipate in such conditions.

“We must find ways to survive,” says Nihal, stirring the pot gently to ensure she doesn’t knock over the small gas oven at the back of her minivan. “I used to have a market in the city but lost it to the earthquake. Now I sell cigarettes and coffee out of my car.”

Nihal’s stand is among the local vendors slowly reappearing across the city. Where the streets are clear enough, restaurants, hair salons, and markets operate from cars and makeshift tents to meet daily needs. Three empty stools were placed next to her car, a heartbreaking reminder of better days when countless chairs from coffee houses spilled out onto sidewalks. Despite water scarcity and no electricity, she brewed me a cup of traditional coffee like she would have served in her market or home, now in a paper cup instead of glass.

A military vehicle passed. I asked Nihal about the soldiers. She explained that the police and army protect what remains of local establishments and cultural heritage sites from looting. “We needed them the most the first three days of the earthquake, but no one was to be found,” she said. The first three days refer to what many see as the worst of this catastrophe. Every person tells me their version of hell, the first three days.

“Most people who died froze from the cold. Others died begging for help. Those who survived listened to their screams for days.”

I am reminded that I am standing on a graveyard of over 50,000 people.

Stitching back communities: Islahiye, Gaziantep Province, and Samandagi, Hatay Province

“Healing happens collectively,” said Sureya Aslan. I met her in the city of Islahiye, the second most damaged city in the southeastern province of Gaziantep, in the temporary housing area built for survivors known as Kalyon Container City. Since losing her home, Sureya has worked to revive the local Community Education Center.

Sureya pointed to a row of sewing machines neatly placed across the tent, reminiscent of a factory line. “We dug out eighty sewing machines, built workshops in tent cities, and now operate educational centers across container camps.” In five months, they sewed 4,500 pairs of underwear and over 1,000 pairs of pajamas for the community.

In Samandagi of Hatay Province, I met with another teacher, Semiha Gulsen, who organizes local craft workshops across container camps five times a week. “We make things, talk, laugh, and tend to our wounds together,” she said. “This is a way for us to rehabilitate.”

Regrowing roots: Defne, Hatay Province

“Since the earthquake, I feel like I am growing roots beneath my feet. I feel more tied to this land than ever,” said Emel Duman, the owner of one of the few silkworm farms in Hatay Province. We met in a small enclosure next to the collapsed room where they used to wash raw silk. She serves me coffee in a suvari, a traditional cup, and homemade mulberry fruit roll-ups.

Emel’s silkworm farm and weaving atelier once hired people from nearby villages, but migration out of the area has made it difficult to resume normal operations. Their showroom, which used to display finished textiles, now houses everything—the silkworms, the looms, and their tailor.

Yet Emel is fiercely optimistic and unwavering in her dedication to resume her craft. “We must pass the silk tradition down to the next generation, so it survives.”

Aylin Sayek echoes the sentiment: “We have almost no tangible heritage left, so our intangible heritage is our foremost priority.” As the director of the Sayek House of Culture in Arsuz, she has been working to implement a silk-weaving workshop for the women in the area. Beginning in March 2024, her project will provide thirty women with theoretical and practical training in silk weaving over six months.

The living conditions and circumstances changed drastically in Arsuz following the earthquake. “The need for our foundation to implement social projects has increased,” Aylin said. “For the first three months, our priority was to address primary needs like food, clothing, hygiene kits, but now we are working on projects to help our community in the long run—mainly children, youth, and women.”

Aylin stressed the importance of centering the community in the recovery efforts to ensure that the cities serve the people and not the other way around. For cities like Antakya with diverse demographics, the ability of local communities to have a say in the post-earthquake recovery and community-building efforts is a matter of survival.

Sule Can, a lecturer at Binghamton University’s Center for Middle East and North Africa Studies from Samandagi in Hatay Province and of Arab origin, echoed similar concerns over changing demographics. Sule warns against the risk of assimilation: “The increasing migration out of [our cities] and changing demographics brings the risk of losing our collective rituals and cultural memory.” Sule stressed the importance of making local communities the key decision makers in recovery efforts to ensure the city is repaired according to the community’s needs.

“We are not just vessels of a culture. We are the active practitioners of a living culture who will pass it to the next generations.”

Resisting erasure: Vakifli Village, Samandagi, and Iskenderun, Hatay Province

In the Armenian-majority village of Vakifli, I met Elena Capar, a founding member of the village cooperative and a staff member of the local Musa Dagh Museum. A Greek Orthodox of Arab origin, she first came to the village twenty-seven years ago when she married her Armenian husband. Since then, she has learned the Armenian language, taught it to her child, and called Vakifli home for almost three decades.

“We used to have thirty-five homes with 130 residents in the village. After the earthquake, many people had to leave, and we have thirty residents left,” Elena explained. Out of the thirty-five homes, thirteen are awaiting demolition.

She gives tours of the Musa Dagh Armenian Museum, which tells the story of the village and the local community’s unique language, traditions, and folk rituals. The museum has been curated with community participation, providing a space to exhibit the rich presence of Armenian culture on the land.

Elena has worked to revitalize the village cooperative to provide a source of income for the community and an incentive to stay. An assurance of return follows every mention of a relative, friend, or neighbor leaving. “They will come back. They have to,” she told me.

The government hasn’t put enough care into repairing the city in a way that will ensure humane living conditions for those left behind. Even so, leaving is not an option for minority communities like the Armenians of Vakifli. Without its people, Vakifli faces the threat of being erased of its living identity, history, and memory.

I drove to Iskenderun to meet with Misel Uyar, a member of the local Greek Orthodox community and a writer for Nehna, a social platform tasked to educate, advocate, and raise awareness about the Orthodox community in Hatay Province. Translating to “Us” in the local Arabic dialect, Nehna aims to resist the cultural erasure of local Greek Orthodox culture and the weakening of local social networks.

When Misel asked to meet at the Greek Orthodox Church of Iskenderun, the Church of Mar Circos, I ignorantly assumed it was out of convenience. But as I made my way past the pristine bricks of the arched gate, Misel reminded me that I was entering a survival story.

“We picked the material for the water tanks from the rubble to provide clean water for our community.” The tents that once housed soldiers and earthquake survivors still stood beside tombstones carved with names in Greek, Arabic, French, and English.

Like many others I talked with, Misel told me that there is a general feeling of fear regarding the future of their city. “Our heritage is at the core of this land. For many ethnic and religious minorities in Turkey, owning land means survival.” He tells me that even before the earthquake, like many other members of the local Greek Orthodox community, he suffered through new zoning laws and the loss of his personal land. “If you remove our land, you force us to migrate.” For many ethnic minority communities like the Greek Orthodox Community of Iskenderun, losing land will inevitably lead to migration out of the motherland.

Misel says the land disputes reflect a greater issue regarding the Turkish government’s cultural heritage and tourism policy. “The government reduces us to an object of cultural diversity, a commodity for tourism. I am frustrated by this narrative because our Greek Orthodox heritage is also at the core of this land.”

Tending to collective wounds: Iskenderun, Hatay Province

In Iskenderun, I met another woman working to keep residents from leaving the city.

Chef Ebru Baybara Demir founded Gönül Mutfagimiz (“Our Hearts Kitchen”), a social initiative that provides warm meals to earthquake survivors. Ebru is from the eastern city of Mardin, which was spared from the earthquake. Since February 6, 2023, more than 3,500 volunteers from around Türkiye have joined her mission. Volunteers work shoulder to shoulder while listening to traditional ballads in Kurdish and Turkish.

“We are desperately clinging to our cultural heritage because culture sustains our people,” she said. “We keep it alive so that it will keep us alive, too.”

On the fortieth day after the earthquake, she and the volunteers cooked a traditional dish called hrisi, made of meat and wheat, for the local Alevi villages. After the community-led prayers, they served 40,000 portions. “We served homemade pickles with the hrisi,”Ebru said. “Those pickles were people’s favorite. So many people told us how much they have missed it and enjoyed having it again.”

Food is never just physical sustenance. In a devastated city, sometimes community care is the pickle served with a traditional dish prepared by people who give attention to the small details so often lost at an institutional level. Out of all the acts of care I witnessed, small kindnesses like this one struck me the most. Healing, I learned, is a compilation of small moments that gently salvage what has been ruptured.

Regrounding in Ancestral Land: Samandagi, Hatay Province

On my last visit to Antakya in July, I returned to Samandagi to attend the 2023 Evvel Temmuz Culture and Art Festival. The two-week event included concerts, movie screenings, and panel discussions about community needs and recovery. According to an interview with one of the festival organizers, the local Arab Alevi and Christian communities have long celebrated Evvel Temmuz as a celebration of harvest, abundance, and rebirth and an offering to Tammuz, the Mesopotamian god of fertility. Since 1980, the festival has been associated with youth movements, the uprisings against the Turkish coup d’état, and the cultural resistance of minority nations.

During the panel “Understanding Cultural Heritage in the Earthquake Zone,” Sule Can warned against the risks of urban planning projects that center monuments instead of communities. Sule stressed that prioritizing commercial gains from tourism over community engagement has the risk of museumification of living heritage sites. “We must repair and understand tangible heritage alongside intangible heritages, because intangible heritages are our collective memory, which is the very thing that gives meaning to these monuments.”

“The biggest risk we are facing is the threat of losing the unique sociocultural texture of Antakya,” said Dr. Tugce Tezer, an urban planner and associate professor at Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University who has dedicated her academic career to understanding Antakya. “Maybe it will take a generation to repair Antakya to what it used to be… It is vital that the repair period is handled with care.”

No other province impacted by the earthquake has articulated a voice for itself like the people of Hatay. For the last year, they have written their story of repair, exploring ways to heal beyond state-sanctioned efforts and survive as an act of resistance. Through city council meetings, oral history work, and storytelling through the Nehna network, and a public forum on Antakya’s living heritage, Hatay has been writing its narrative and, in the words of bell hooks, “talking back.”

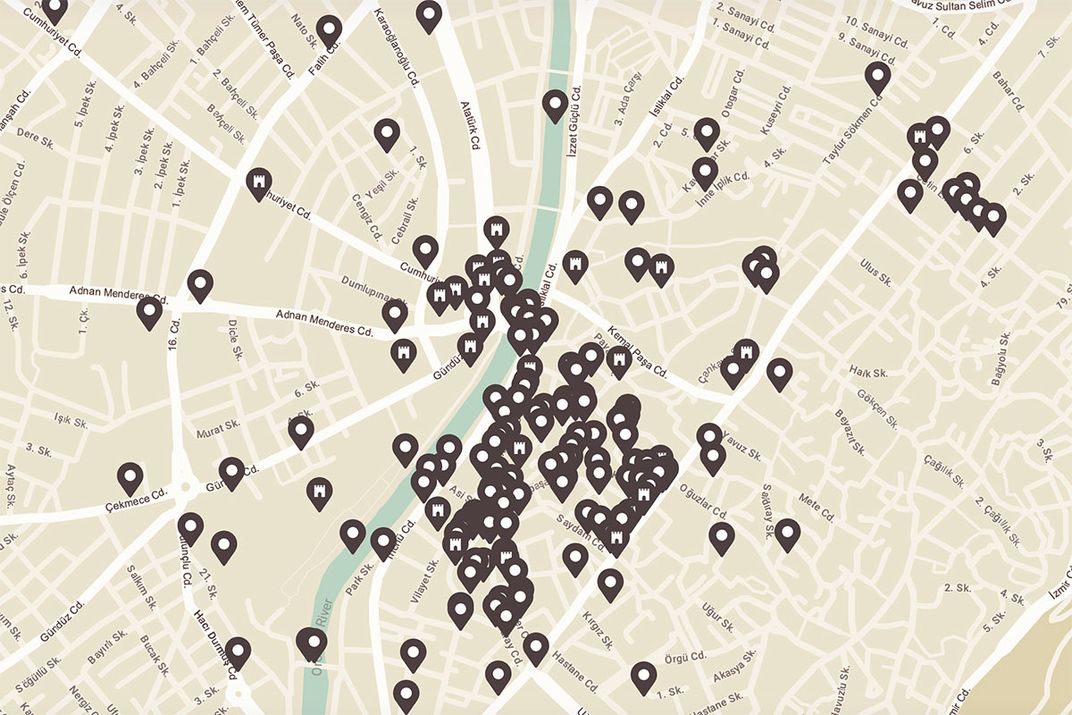

On December 16, 2023, ten months after the earthquake, Nehna launched the “Beledna Memory Map” of Hatay. The project is an online memory space where residents and visitors can pin memories, photos, stories, and emotions as journal entries on an interactive map. Since its launch, the map has been growing exponentially. Developed by Gozde Aydin, Nurbana Husrevoglu, and Anil B. Poyrazoglu, the Memory Map aims to combat the loss of sense of space. The creators hope that this unique archive will challenge the narrative of Hatay as a geography of perpetual disaster and create a counternarrative of Hatay as a space of solidarity, resistance, diversity, and a unique story for those willing to listen.

On January 29, 2024, Living Heritage: A collective statement for community-driven post-earthquake reconstruction in Antakya was published following a public forum on Antakya’s living heritage. The statement defines “living heritage” as a collection of spaces, people, knowledge, monuments, historical events, and memory. It also identifies six fundamental challenges to repairing the city in a way that protects living heritage: the lack of infrastructure, such as access to safe drinking water, food, and energy; the public health hazards and pollution that endanger the population as well as natural resources; haphazard urban development; the loss of sense of space; and displacement, gentrification, and tourism-based urban development, which all leads to forced migration out of the city.

In her statement of solidarity, Sule emphasizes that collective anger lies at the heart of everyday acts of solidarity against the political violence that targets the living heritage of the city.

What will fill the void left by people? I ask myself again, my fear replaced by hope. I hear the wisdom of Hilal, Nihal, Emel, Ebru, Elena, Aylin, Misel, Tugce, and Sule Can assure me:

The living will fill the void.

Ladin Akcacioglu is an intern at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage and a senior at Mount Holyoke College, studying politics of heritage and material culture, with a focus on the Middle East and North Africa.

This story is dedicated to the resilient women of my country whose selfless labor, boundless wisdom, and kindness are often taken for granted. Everything I am, everything I do, I owe it to you. Thank you. Bu yazıyı, ülkemin metanetli, bilge, merhametli ve emekleri görmezden gelinen tüm kadınlarına ithaf ediyorum. Sizin sayenizde varım. Teşekkür ederim.