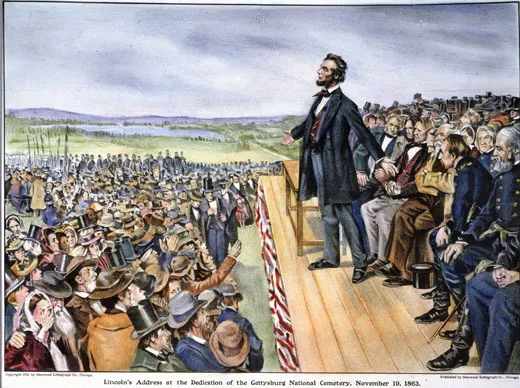

Ask an Expert: What Did Abraham Lincoln’s Voice Sound Like?

Civil War scholar Harold Holzer helps to decode what spectators heard when the 16th president spoke

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Lincolns-Voice-631.jpg)

I suspect that when people imagine Abraham Lincoln and the way he sounded, many imagine him as a bass, or at least a deep baritone. Perhaps this is because of his large stature and the resounding nature of his words. Certainly, the tradition of oratory in the 1850s would support the assumption. “Usually people with centurion, basso profundo voices dominated American politics,” says Harold Holzer, a leading Lincoln scholar. Then, of course, there are the casting choices of film and TV directors over the years. “It can’t get any deeper than Gregory Peck,” says Holzer. Peck played Lincoln in the 1980s TV miniseries The Blue and the Gray.

But, unfortunately, no recordings of Lincoln’s voice exist, since he died 12 years before Thomas Edison invented the phonograph, the first device to record and play back sound. If anyone had an educated guess as to how it sounded though, it would be Holzer, who has written 40 books on Lincoln and the Civil War. The author has pored over reports of Lincoln’s public appearances on speaking tours, eyewitness accounts told to Lincoln’s law partner William Herndon and newspaper commentaries about the Lincoln-Douglas debates, and, surprisingly, he says, one of the only things that can be said with certainty is that Lincoln was a tenor.

“Lincoln’s voice, as far as period descriptions go, was a little shriller, a little higher,” says Holzer. It would be a mistake to say that his voice was squeaky though. “People said that his voice carried into crowds beautifully. Just because the tone was high doesn’t mean it wasn’t far-reaching,” he says.

When Holzer was researching his 2004 book Lincoln at Cooper Union, he noticed an interesting consistency in the accounts of those who attended Lincoln’s speaking tour in February and March 1860. “They all seem to say, for the first ten minutes I couldn’t believe the way he looked, the way he sounded, his accent. But after ten minutes, the flash of his eyes, the ease of his presentation overcame all doubts, and I was enraptured,” says Holzer. “I am paraphrasing, but there is ten minutes of saying, what the heck is that, and then all of a sudden it’s the ideas that supersede whatever flaws there are.” Lincoln’s voice needed a little time to warm up, and Holzer refers to this ten-minute mark as the “magical moment when the voice fell into gear.”

He recalls a critic saying something to this effect about Katharine Hepburn’s similarly startling voice: “When she begins to talk, you wonder why anyone would talk like that. But by the time the second act begins, you wonder why everyone doesn’t talk like that.” Says Holzer: “It’s that combination of gesture, mannerism and unusual timbre of voice that really original people have. It takes a little bit to get used to.”

Actor Sam Waterston has played Lincoln on screen, in Ken Burns’ The Civil War and Gore Vidal’s Lincoln, and on Broadway, in Abe Lincoln in Illinois. To prepare for the role in the 1980s, he went to the Library of Congress and listened to Works Progress Administration tapes of stories told by people from the regions where Lincoln lived. (Some of the older people on the tapes were born when Lincoln was alive.) Lincoln’s accent was a blend of Indiana and Kentucky. “It was hard to know whether it was more Hoosier or blue grass,” says Holzer. The way he spelled words, such as “inaugural” as “inaugerel,” gives some clue as to how he pronounced them.

Despite his twang, Lincoln was “no country bumpkin,” Holzer clarifies. “This was a man who committed to memory and recited Shakespearean soliloquies aloud. He knew how to move into King’s English. He could do Scottish accents because he loved Robert Burns. He was a voracious reader and a lover of poetry and cadence. When he writes something like the Second Inaugural, you see the use of alliteration and triplets. ‘Of the people, by the people and for the people’ is the most famous example,” he says. “This was a person who truly understood not only the art of writing but also the art of speaking. People should remember that, though we have no accurate memorial of his voice, this is a man who wrote to be heard. Only parenthetically did he write to be read.”

According to William Herndon, Lincoln didn’t saw wood or swat bees, meaning he did not gesture too much. Apparently, he didn’t roam the stage either. Herndon once wrote that you could put a silver dollar in between Lincoln’s feet at the start of a speech and it would be there, undisturbed, at the end. “He was very still,” says Holzer. “He let that voice that we question and his appearance and the words themselves provide the drama.”

Of the actors who have played Lincoln, “Waterston catches it for me,” says Holzer. “Although he is from Massachusetts, he gets that twang down, and he’s got a high voice that sometimes lapses into very high.”

It will be interesting to see what Daniel Day-Lewis, who is known to go to great lengths to get into character, does with the part. He is slated to play the president in Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln, a 2012 release based on the book Team of Rivals by Doris Kearns Goodwin.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)