Who Discovered the North Pole?

A century ago, explorer Robert Peary earned fame for discovering the North Pole, but did Frederick Cook get there first?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Cook-Peary-Arctic-631.jpg)

On September 7, 1909, readers of the New York Times awakened to a stunning front-page headline: "Peary Discovers the North Pole After Eight Trials in 23 Years." The North Pole was one of the last remaining laurels of earthly exploration, a prize for which countless explorers from many nations had suffered and died for 300 years. And here was the American explorer Robert E. Peary sending word from Indian Harbour, Labrador, that he had reached the pole in April 1909, one hundred years ago this month. The Times story alone would have been astounding. But it wasn't alone.

A week earlier, the New York Herald had printed its own front-page headline: "The North Pole is Discovered by Dr. Frederick A. Cook." Cook, an American explorer who had seemingly returned from the dead after more than a year in the Arctic, claimed to have reached the pole in April 1908—a full year before Peary.

Anyone who read the two headlines would know that the North Pole could be "discovered" only once. The question then was: Who had done it? In classrooms and textbooks, Peary was long anointed the discoverer of the North Pole—until 1988, when a re-examination of his records commissioned by the National Geographic Society, a major sponsor of his expeditions, concluded that Peary's evidence never proved his claim and suggested that he knew he might have fallen short. Cook's claim, meanwhile, has come to rest in a sort of polar twilight, neither proved nor disproved, although his descriptions of the Arctic region—made public before Peary's—were verified by later explorers. Today, on the centennial of Peary's claimed arrival, the bigger question isn't so much who as how: How did Peary's claim to the North Pole trump Cook's?

In 1909, the journalist Lincoln Steffens hailed the battle over Peary's and Cook's competing claims as the story of the century. "Whatever the truth is, the situation is as wonderful as the Pole," he wrote. "And whatever they found there, those explorers, they have left there a story as great as a continent."

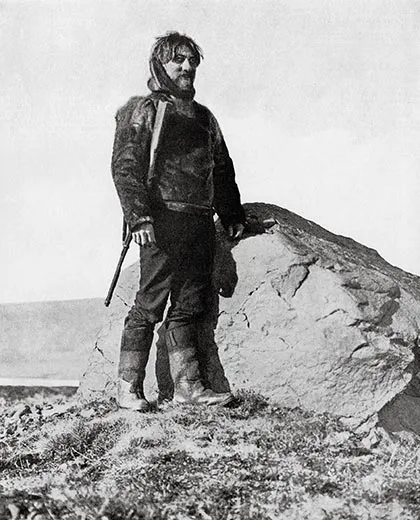

They started out as friends and shipmates. Cook had graduated from New York University Medical School in 1890; just before he received his exam results, his wife and baby died in childbirth. Emotionally shattered, the 25-year-old doctor sought escape in articles and books on exploration, and the next year he read that Peary, a civil engineer with a U.S. Navy commission, was seeking volunteers, including a physician, for an expedition to Greenland. "It was as if a door to a prison cell had opened," Cook would later write. "I felt the first indomitable, commanding call of the Northland." After Cook joined Peary's 1891 Greenland expedition, Peary shattered his leg in a shipboard accident; Cook set Peary's two broken bones. Peary would credit the doctor's "unruffled patience and coolness in an emergency" in his book Northward Over the Great Ice.

For his part, Peary had come by his wanderlust after completing naval assignments overseeing pier construction in Key West, Florida, and surveying in Nicaragua for a proposed ship canal (later built in Panama) in the 1880s. Reading an account of a Swedish explorer's failed attempt to become the first person to cross the Greenland ice cap, Peary borrowed $500 from his mother, outfitted himself and bought passage on a ship that left Sydney, Nova Scotia, in May 1886. But his attempt to cross the cap, during a summer-long sledge trip, ended when uncertain ice conditions and dwindling supplies forced him back. Upon returning to a new Navy assignment in Washington, D.C., he wrote his mother, "My last trip brought my name before the world; my next will give me a standing in the world....I will be foremost in the highest circles in the capital, and make powerful friends with whom I can shape my future instead of letting it come as it will....Remember, mother, I must have fame."

Peary, born in 1856, was one of the last of the imperialistic explorers, chasing fame at any cost and caring for the local people's well-being only to the extent that it might affect their usefulness to him. (In Greenland in 1897, he ordered his men to open the graves of several natives who had died in an epidemic the previous year—then sold their remains to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City as anthropological specimens. He also brought back living natives—two men, a woman and three youngsters—and dropped them off for study at the museum; within a year four of them were dead from a strain of influenza to which they had no resistance.)

Cook, born in 1865, would join a new wave of explorers who took a keen interest in the indigenous peoples they came across. For years, in both the Arctic and the Antarctic, he learned their dialects and adopted their diet.

Differences between the two men began to surface after their first trip to Greenland. In 1893, Cook backed out of another Arctic journey because of a contract prohibiting any expedition member from publishing anything about the trip before Peary published his account of it. Cook wanted to publish the results of an ethnological study of Arctic natives, but Peary said it would set "a bad precedent." They went their separate ways—until 1901, when Peary was believed to be lost in the Arctic and his family and supporters turned to Cook for help. Cook sailed north on a rescue ship, found Peary and treated him for ailments ranging from scurvy to heart problems.

Cook also traveled on his own to the Antarctic and made two attempts to scale Alaska's Mount McKinley, claiming to be the first to succeed in 1906. Peary, for his part, made another attempt to reach the North Pole in 1905-06, his sixth Arctic expedition. By then, he had come to think of the pole as his birthright.

Any endeavor to reach the pole is complicated by this fact: unlike the South Pole, which lies on a landmass, the North Pole lies on drifting sea ice. After fixing your position at 90 degrees north—where all directions point south—there is no way to mark the spot, because the ice is constantly moving.

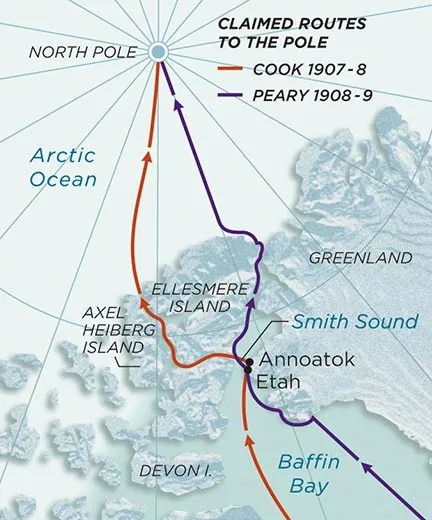

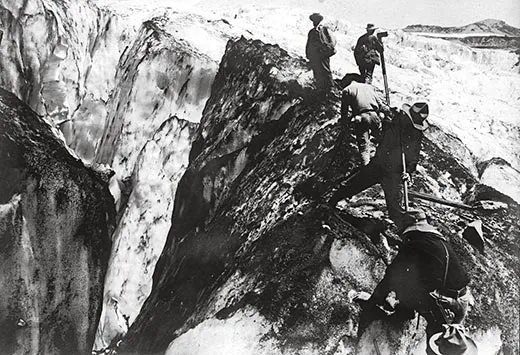

Cook's expedition to the pole departed Gloucester, Massachusetts, in July 1907 on a schooner to northern Greenland. There, at Annoatok, a native settlement 700 miles from the pole, he established a base camp and wintered over. He left for the pole in February 1908 with a party of nine natives and 11 light sledges pulled by 103 dogs, planning to follow an untried but promising route described by Otto Sverdrup, the leader of an 1898-1902 Norwegian mapping party.

According to Cook's book My Attainment of the Pole, his party followed the musk ox feeding grounds that Sverdrup had observed, through Ellesmere and Axel Heiberg islands to Cape Stallworthy at the edge of the frozen Arctic Sea. The men had the advantage of eating fresh meat and conserving their stores of pemmican (a greasy mixture of fat and protein that was a staple for Arctic explorers) made of beef, ox tenderloin and walrus. As the party pushed northward, members of Cook's support team turned back as planned, leaving him with two native hunters, Etukishook and Ahwelah. In 24 days Cook's party went 360 miles—a daily average of 15 miles. Cook was the first to describe a frozen polar sea in continuous motion and, at 88 degrees north, an enormous, "flat-topped" ice island, higher and thicker than sea ice.

For days, Cook wrote, he and his companions struggled through a violent wind that made every breath painful. At noon on April 21, 1908, he used his custom-made French sextant to determine that they were "at a spot which was as near as possible" to the pole. At the time, speculation about what was at the pole ranged from an open sea to a lost civilization. Cook wrote that he and his men stayed there for two days, during which the doctor reported taking more observations with his sextant to confirm their position. Before leaving, he said, he deposited a note in a brass tube, which he buried in a crevasse.

The return trip almost did them in.

Cook, like other Arctic explorers of the day, had assumed that anyone returning from the pole would drift eastward with the polar ice. However, he would be the first to report a westerly drift—after he and his party were carried 100 miles west of their planned route, far from supplies they had cached on land. In many places the ice cracked, creating sections of open water. Without the collapsible boat they had brought along, Cook wrote, they would have been cut off any number of times. When winter's onslaught made travel impossible, the three men hunkered down for four months in a cave on Devon Island, south of Ellesmere Island. After they ran out of ammunition, they hunted with spears. In February 1909, the weather and ice improved enough to allow them to walk across frozen Smith Sound back to Annoatok, where they arrived—emaciated and arrayed in rags of fur—in April 1909, some 14 months after they had set out for the pole.

At Annoatok, Cook met Harry Whitney, an American sportsman on an Arctic hunting trip, who told him that many people believed Cook had disappeared and died. Whitney also told him that Peary had departed from a camp just south of Annoatok on his own North Pole expedition eight months earlier, in August 1908.

Peary had assembled his customary large party—50 men, nearly as many heavy sledges and 246 dogs to pull them—for use in a relay sledge train that would deposit supplies ahead of him. He called this the "Peary system" and was using it even though it had failed him in his 1906 attempt, when the ice split and open water kept him from his caches for long periods. On this try, Peary again faced stretches of open water that could extend for miles. He had no boat, so his party had to wait, sometimes for days, for the ice to close up.

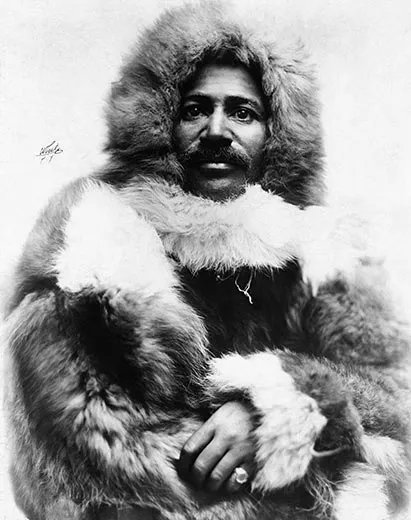

Peary's party advanced 280 miles in a month. When adjusted for the days they were held up, their average progress came to about 13 miles a day. When they were some 134 miles from the pole, Peary sent everyone back except four natives and Matthew Henson, an African-American from Maryland who had accompanied him on his previous Arctic expeditions. A few days later—on April 6, 1909—at the end of an exhausting day's march, Henson, who could not use a sextant, had a "feeling" they were at the pole, he later told the Boston American.

"We are now at the Pole, are we not?" Henson said he asked Peary.

"I do not suppose that we can swear that we are exactly at the Pole," Peary replied, according to Henson.

He said Peary then reached into his outer garment and took out a folded American flag sewn by his wife and fastened it to a staff, which he stuck atop an igloo his native companions had built. Then everyone turned in for some much-needed sleep.

The next day, in Henson's account, Peary took a navigational sight with his sextant, though he did not tell Henson the result; Peary put a diagonal strip of the flag, together with a note, in an empty tin and buried it in the ice. Then they turned toward home.

While Peary made his way south, Cook was recovering his strength at Annoatok. Having befriended Whitney, he told him about his trip to the pole but asked that he say nothing until Cook could make his own announcement. With no scheduled ship traffic so far north, Cook planned to sledge 700 miles south to the Danish trading post of Upernavik, catch a ship to Copenhagen and another to New York City. He had no illusions about the difficulties involved—the sledge trip would involve climbing mountains and glaciers and crossing sections of open water when the ice was in motion—but he declined Whitney's offer of passage on a chartered vessel due at summer's end to take the sportsman home to New York. Cook thought his route would be faster.

Etukishook and Ahwelah had returned to their village just south of Annoatok, so Cook enlisted two other natives to accompany him. The day before they were to leave, one of the two got sick, which meant that Cook would have to leave a sledge behind. Whitney suggested that he also leave behind anything not essential for his trip, promising to deliver the abandoned possessions to Cook in New York. Cook agreed.

In addition to meteorological data and ethnological collections, Cook boxed up his expedition records, except for his diary, and his instruments, including his sextant, compass, barometer and thermometer. He wouldn't be needing them because he would be following the coastline south. Leaving three trunk-size boxes with Whitney, Cook left Annoatok the third week of April 1909 and arrived a month later at Upernavik, where he told Danish officals of his conquest of the pole.

It was not until early August that a ship bound for Copenhagen, the Hans Egede, docked in Upernavik. For the three weeks it took to cross the North Atlantic, Cook entertained passengers and crew alike with spellbinding accounts of his expedition. The ship's captain, who understood the news value of Cook's claim, suggested he get word of it out. So on September 1, 1909, the Hans Egede made an unscheduled stop at Lerwick, in the Shetland Islands. At the town's telegraph station, Cook wired the New York Herald, which had covered explorers and their exploits since Stanley encountered Livingstone in Africa 30 years earlier. "Reached North Pole April 21, 1908," Cook began. He explained that he would leave an exclusive 2,000-word story for the newspaper with the Danish consul at Lerwick. The next day, the Herald ran Cook's story under its "Discovered by Dr. Frederick A. Cook" headline.

In Copenhagen, Cook was received by King Frederick. In gratitude for the Danes' hospitality, Cook promised in the king's presence that he would send his polar records to geography experts at the University of Copenhagen for their examination. "I offer my observations to science," he said.

While Cook was steaming for Copenhagen, Harry Whitney waited in vain for his chartered vessel to arrive. Not until August would another ship stop in northern Greenland: the Roosevelt, built for Peary by his sponsors and named after Theodore Roosevelt. On board, Peary was returning from his own polar expedition, although up to that point he had told no one—not even the ship's crew—that he had reached the North Pole. Nor did he seem to be in any hurry to do so; the Roosevelt had been making a leisurely journey, stopping to hunt walrus in Smith Sound.

In Annoatok, Peary's men heard from natives that Cook and two natives had made it to the pole the previous year. Peary immediately queried Whitney, who said he knew only Cook had returned safely from a trip to the Far North. Peary then ordered Cook's two companions, Etukishook and Ahwelah, brought to his ship for questioning. Arctic natives of the day had no knowledge of latitude and longitude, and they did not use maps; they testified about distances only in relation to the number of days traveled. In a later interview with a reporter, Whitney, who unlike Peary was fluent in the natives' dialect, would say the two told him they had been confused by the white men's questions and did not understand the papers on which they were instructed to make marks.

Whitney accepted Peary's offer to leave Greenland on the Roosevelt. Whitney later told the New York Herald that a line of natives toted his possessions aboard under Peary's watchful gaze.

"Have you anything belonging to Dr. Cook?" Whitney told the newspaper Peary asked him.

Whitney answered that he had Cook's instruments and his records from his journey.

"Well, I don't want any of them aboard this ship," Peary replied, according to Whitney.

Believing that he had no choice, Whitney secreted Cook's possessions among some large rocks near the shoreline. The Roosevelt then sailed south with Whitney aboard.

On August 26, the vessel stopped at Cape York, in northwest Greenland, where a note from the skipper of an American whaler awaited Peary. It said that Cook was en route to Copenhagen to announce that he had discovered the North Pole on April 21, 1908. Native rumor was one thing; this was infuriating. Peary vented his rage to anyone who would listen, promising to tell the world a story that would puncture Cook's bubble. Peary ordered his ship to get underway immediately and make full speed for the nearest wireless station—1,500 miles away, at Indian Harbour, Labrador. Peary had an urgent announcement to make. On September 5, 1909, the Roosevelt dropped anchor at Indian Harbour. The next morning Peary wired the New York Times, to which he had sold the rights to his polar story for $4,000, subject to reimbursement if he did not achieve his goal. "Stars and Stripes nailed to North Pole," his message read.

Two days later, at Battle Harbour, farther down the Labrador coast, Peary sent the Times a 200-word summary and added: "Don't let Cook story worry you. Have him nailed." The next day, the Times ran his abbreviated account.

Arriving in Nova Scotia on September 21, Peary left the Roosevelt to take a train to Maine. At one stop en route, he met with Thomas Hubbard and Herbert Bridgman, officers of the Peary Arctic Club, a group of wealthy businessmen who financed Peary's expeditions in exchange for having his discoveries named for them on maps. The three men began to shape a strategy to undermine Cook's claim to the pole.

When they reached Bar Harbor, Maine, Hubbard had a statement for the press on Peary's behalf: "Concerning Dr. Cook...let him submit his records and data to some competent authority, and let that authority draw its own conclusions from the notes and records....What proof Commander Peary has that Dr. Cook was not at the pole may be submitted later."

The same day that Peary arrived in Nova Scotia, September 21, Cook arrived in New York to the cheers of hundreds of thousands of people lining the streets. He issued a statement that began, "I have come from the Pole." The next day he met with some 40 reporters for two hours at the Waldorf-Astoria hotel. Asked if he objected to showing his polar diary, Cook "showed freely" a notebook of 176 pages, each filled with "fifty or sixty lines of penciled writing in the most minute characters," according to accounts in two Philadelphia papers, the Evening Bulletin and the Public Ledger. Asked how he fixed his position at the pole, Cook said by measuring the sun's altitude in the sky. Would he produce his sextant? Cook said his instruments and records were en route to New York and that arrangements had been made for experts to verify their accuracy.

Four days later, he received a wire from Harry Whitney. "Peary would allow nothing belonging to you on board," it read. "...See you soon. Explain all."

Cook would later write that he was seized by "heartsickness" as he realized the implications of Whitney's message. Still, he kept giving interviews about his trek, providing details on his final dash to the pole and his year-long struggle to survive the return journey. Peary had told an Associated Press reporter in Battle Harbour that he would wait for Cook to "issue a complete authorized version of his journey" before making his own details public. Peary's strategy of withholding information gave him the advantage of seeing what Cook had by way of polar descriptions before offering his own.

In the short term, however, Cook's fuller accounts helped him. With the two battling claims for the pole, newspapers polled their readers on which explorer they favored. Pittsburgh Press readers supported Cook, 73,238 to 2,814. Watertown (N.Y.) Times readers favored Cook by a ratio of three to one. The Toledo Blade counted 550 votes for Cook, 10 for Peary. But as September turned to October, Peary's campaign against Cook picked up momentum.

First, the Peary Arctic Club questioned Cook's claim to have scaled Mount McKinley in 1906. For years a blacksmith named Edward Barrill, who had accompanied Cook on the climb, had been telling friends, neighbors and reporters about their historic ascent. But the Peary Arctic Club released an affidavit signed by Barrill and notarized on October 4 saying the pair had never made it all the way to the top. The document was published in the New York Globe—which was owned by Peary Arctic Club president Thomas Hubbard, who declared that the McKinley affair cast doubt on Cook's polar claim.

On October 24, the New York Herald reported that before the affidavit was signed, Barrill had met with Peary's representatives to discuss financial compensation for calling Cook a liar. The paper quoted Barrill's business partner, C. C. Bridgeford, as saying Barrill had told him, "This means from $5,000 to $10,000 to me." (Later, Cook's McKinley claim would be challenged by others and in more detail. Now, many members of the mountaineering community dismiss the notion that he reached the summit.)

A week after Barrill's affidavit appeared in the Globe, Peary released a transcript of the interrogation of Etukishook and Ahwelah aboard the Roosevelt. The men were quoted as saying they and Cook had traveled only a few days north on the ice cap, and a map on which they were said to have marked their route was offered as evidence.

Also in October, the National Geographic Society—which had long supported Peary's work and put up $1,000 for the latest polar expedition—appointed a three-man committee to examine his data. One member was a friend of Peary's; another was head of the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, to which Peary had been officially assigned for his final expedition, and the third had been quoted in the New York Times as "a skeptic on the question of the discovery of the Pole by Cook."

On the afternoon of November 1, the three men met with Peary and examined some records from his journey; that evening, they looked at—but according to Peary's own account did not carefully examine—the explorer's instruments in a trunk in the poorly lit baggage room of a train station in Washington, D.C. Two days later, the committee announced that Peary had indeed reached the North Pole.

By then, Cook had to cancel a lecture tour that he had just begun because of laryngitis and what he called "mental depression." In late November, drawing on his diary, he completed his promised report to the University of Copenhagen. (He chose not to send his diary to Denmark for fear of losing it.) In December, the university—whose experts had been expecting original records—announced that Cook's claim was "not proven." Many U.S. newspapers and readers took that finding to mean "disproved."

"The decision of the university is, of course, final," the U.S. minister to Denmark, Maurice Egan, told the Associated Press on December 22, 1909, "unless the matter should be reopened by the presentation of the material belonging to Cook which Harry Whitney was compelled to leave."

By then, the news coverage, along with the public feting of Peary by his supporters, began to swing the public to his side. Cook did not help his cause when he left for a yearlong exile in Europe, during which he wrote his book about the expedition, My Attainment of the Pole. Though he never returned to the Arctic, Whitney did, reaching northern Greenland in 1910. Reports conflict on how thoroughly he searched for Cook's instruments and records, but in any case he never recovered them. Nor has anyone else in the years since.

In January 1911, Peary appeared before the Naval Affairs Subcommittee of the U.S. House of Representatives to receive what he hoped would be the government's official recognition as the discoverer of the North Pole. He brought along his diary of his journey. Several congressmen were surprised by what they saw—or didn't see—on its pages.

"A very clean kept book," noted Representative Henry T. Helgesen of North Dakota, wondering aloud how that could be, considering the nature of pemmican. "How was it possible to handle this greasy food and without washing write in a diary daily and at the end of two months have that same diary show no finger marks or rough usage?"

To this and other questions Peary gave answers that several subcommittee members would deem wanting. The subcommittee chairman, Representative Thomas S. Butler of Pennsylvania, concluded, "We have your word for it....your word and your proofs. To me, as a member of this committee, I accept your word. But your proofs I know nothing at all about."

The subcommittee approved a bill honoring Peary by a vote of 4 to 3; the minority placed on the record "deep-rooted doubts" about his claim. The bill that passed the House and Senate, and which President William Howard Taft signed that March, eschewed the word "discovery," crediting Peary only with "Arctic exploration resulting in [his] reaching the North Pole." But he was placed on the retired list of the Navy's Corps of Civil Engineers with the rank of rear admiral and given a pension of $6,000 annually.

After what he perceived to be a hostile examination of his work, Peary never again showed his polar diary, field papers or other data. (His family consented to the examination of the records that led to the 1988 National Geographic article concluding that he likely missed his mark.) In fact, he rarely spoke publicly of the North Pole to the day he died of pernicious anemia, on February 20, 1920, at the age of 63.

The early doubts about Cook's claim, most of which emanated from the Peary camp, came to overshadow any contemporaneous doubts about Peary's claim. After Cook returned to the United States in 1911, some members of Congress tried in 1914 and 1915 to reopen the question of who discovered the North Pole, but their efforts faded with the approach of World War I. Cook went into the oil business in Wyoming and Texas, where in 1923 he was indicted on mail-fraud charges related to the pricing of stock in his company. After a trial that saw 283 witnesses—including a bank examiner who testified that Cook's books were in good order—a jury convicted him. "You have at last got to the point where you can't bunco anybody," District Court Judge John Killits berated Cook before he sentenced him to 14 years and nine months in prison.

While Cook was at the federal penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas, some of the land his now-dissolved oil company had leased was found to be part of the Yates Pool, the largest oil find of the century in the continental United States. Paroled in March 1930, Cook told reporters, "I am tired and I am going to rest." He spent his last decade living with his two daughters from his second marriage and their families. President Franklin D. Roosevelt pardoned Cook a few months before he died of complications from a stroke, on August 5, 1940, at the age of 75.

The notes that Peary and Cook reported leaving at the pole have never been found. The first undisputed overland trek to the North Pole wasn't made until 1968, when a party led by a Minnesotan named Ralph Plaisted arrived by snowmobile. But other explorers preceded Plaisted, arriving by air and by sea, and confirmed Cook's original descriptions of the polar sea, ice islands and the westward drift of the polar ice. So the question persists: How did Cook get so much right if he never got to the North Pole in 1908?

Bruce Henderson is the author of True North: Peary, Cook and the Race to the Pole. He teaches writing at Stanford University.

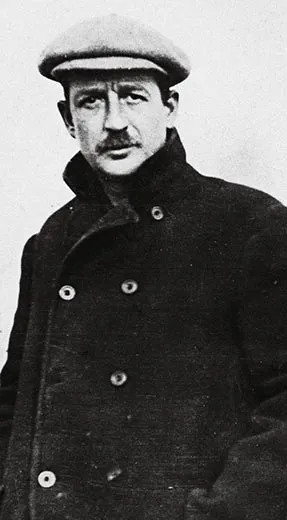

Editor's note: An earlier version of this article featured a photograph that was misidentified as Robert Peary. This version has been updated with a new photograph of Peary.