How Arlington National Cemetery Came to Be

The fight over Robert E. Lee’s beloved home—seized by the U.S. government during the Civil War—went on for decades

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Arlington-military-cemetery-631.jpg)

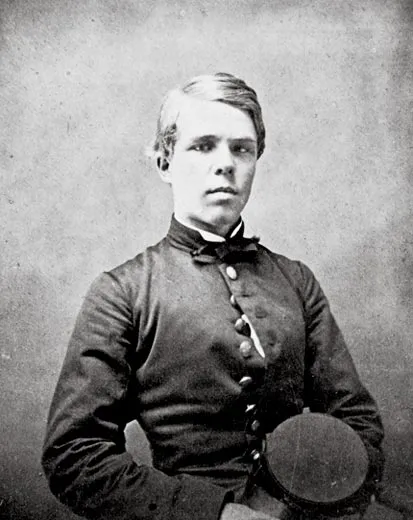

One afternoon in May 1861, a young Union Army officer went rushing into the mansion that commanded the hills across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C. "You must pack up all you value immediately and send it off in the morning," Lt. Orton Williams told Mary Custis Lee, wife of Robert E. Lee, who was away mobilizing Virginia's military forces as the country hurtled toward the bloodiest war in its history.

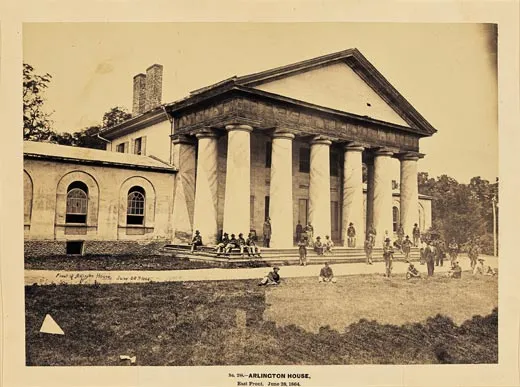

Mary Lee dreaded the thought of abandoning Arlington, the 1,100-acre estate she had inherited from her father, George Washington Parke Custis, upon his death in 1857. Custis, the grandson of Martha Washington, had been adopted by George Washington when Custis' father died in 1781. Beginning in 1802, as the new nation's capital took form across the river, Custis started building Arlington, his showplace mansion. Probably modeled after the Temple of Hephaestus in Athens, the columned house floated among the Virginia hills as if it had been there forever, peering down upon the half-finished capital at its feet. When Custis died, Arlington passed to Mary Lee, his only surviving child, who had grown up, married and raised seven children and buried her parents there. In correspondence, her husband referred to the place as "our dear home," the spot "where my attachments are more strongly placed than at any other place in the world." If possible, his wife felt an even stronger attachment to the property.

On April 12, 1861, Confederate troops had fired on the federal garrison at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, prompting a number of states from the Deep South to join in rebellion. President Abraham Lincoln, newly installed in the White House, called up 75,000 troops to defend the capital. As the spring unfolded, the forces drifted into Washington, set up camp in the unfinished Capitol building, patrolled the city's thoroughfares and scrutinized the Virginia hills for signs of trouble. Although officially uncommitted to the Confederacy, Virginia was expected to join the revolt. When that happened, Union troops would have to take control of Arlington, where the heights offered a perfect platform for artillery—key to the defense or subjugation of the capital. Once the war began, Arlington was easily won. But then it became the prize in a legal and bureaucratic battle that would continue long after the guns fell silent at Appomattox in 1865. The federal government was still wrestling the Lee family for control of the property in 1882, by which time it had been transformed into Arlington National Cemetery, the nation's most hallowed ground.

Orton Williams was not only Mary Lee's cousin and a suitor of her daughter Agnes but also private secretary to General in Chief Winfield Scott of the Union Army.

Working in Scott's office, he had no doubt heard about the Union Army's plans for seizing Arlington, which accounts for his sudden appearance there. That May night, Mrs. Lee supervised some frantic packing by a few of the family's 196 slaves, who boxed the family silver for transfer to Richmond, crated George Washington's and G.W.P. Custis' papers and secured General Lee's files. After organizing her escape, Mary Lee tried to get some sleep, only to be awakened just after dawn by Williams: the Army's advance upon Arlington had been delayed, he said, though it was inevitable. She lingered for several days, sitting for hours in her favorite roost, an arbor south of the mansion. "I never saw the country more beautiful, perfectly radiant," she wrote to her husband. "The yellow jasmine in full bloom and perfuming the air; but a death like stillness prevails everywhere."

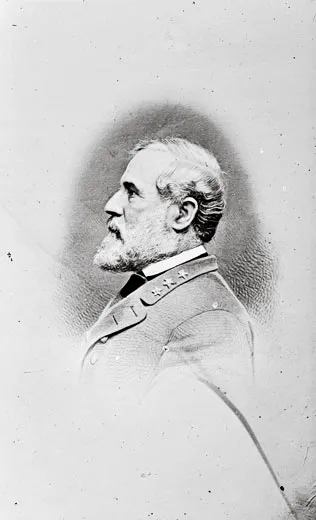

The general, stranded at a desk in Richmond, feared for his wife's safety. "I am very anxious about you," he had written her on April 26. "You have to move, & make arrangements to go to some point of safety....War is inevitable & there is no telling when it will burst around you."

By this time, he almost certainly knew that Arlington would be lost. A newly commissioned brigadier general in the Confederate Army, he had made no provision to hold it by force, choosing instead to concentrate his troops some 20 miles southwest, near a railroad junction at Manassas, Virginia. Meanwhile, Northern newspapers such as the New York Daily Tribune trained their big guns on him—labeling him a traitor for resigning his colonel's commission in the Union Army to go south "in the footsteps of Benedict Arnold!"

The rhetoric grew only more heated with the weather. Former Army comrades who had admired Lee turned against him. None was more outspoken than Brig. Gen. Montgomery C. Meigs, a fellow West Point graduate who had served amicably under Lee in the engineer corps but now considered him an insurgent. "No man who ever took the oath to support the Constitution as an officer of our army or navy...should escape without loss of all his goods & civil rights & expatriation," Meigs wrote to his father. He urged that Lee as well as Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, who also had resigned from the federal Army to join the enemy, and Confederate President Jefferson Davis "should be put formally out of the way if possible by sentence of death [and] executed if caught."

When Johnston resigned, Meigs had taken his job as quartermaster general, which required him to equip, feed and transport a rapidly growing Union Army—a task for which Meigs proved supremely suited. Vain, energetic, vindictive and exceptionally capable, he would back up his belligerent talk in the months and years ahead. His own mother conceded that the youthful Meigs had been "high tempered, unyielding, tyrannical...and very persevering in pursuit of anything he wants." Fighting for control of Arlington, he would become one of Lee's most implacable foes.

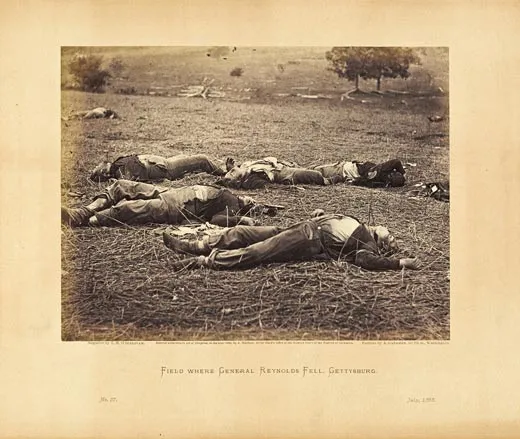

By mid-May, even Mary Lee had to concede that she could not avoid the impending conflict. "I would have greatly preferred remaining at home & having my children around me," she wrote to one of her daughters, "but as it would greatly increase your Father's anxiety I shall go." She made an eerily accurate prediction: "I fear that this will be the scene of conflict & my beautiful home endeared by a thousand associations may become a field of carnage."

She took a final turn in the garden, entrusted the keys to Selina Gray, a slave, and followed her husband's path down the estate's long, winding driveway. Like many others on both sides, she believed that the war would pass quickly.

On May 23, 1861, the voters of Virginia approved an ordinance of secession by a ratio of more than six to one. Within hours, columns of Union forces streamed through Washington and made for the Potomac. At precisely 2 a.m. on May 24, some 14,000 troops began crossing the river into Virginia. They advanced in the moonlight on steamers, on foot and on horseback, in swarms so thick that James Parks, a Lee family slave watching from Arlington, thought they looked "like bees a-coming."

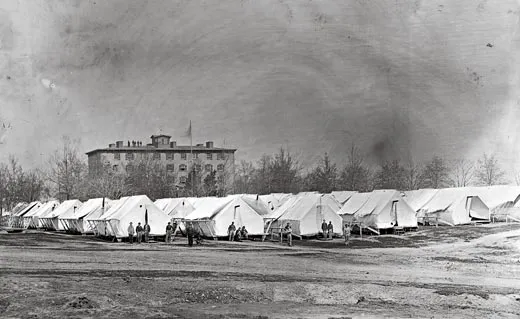

The undefended estate changed hands without a whimper. When the sun rose that morning, the place was teeming with men in blue. They established a tidy village of tents, stoked fires for breakfast and scuttled over the mansion's broad portico with telegrams from the War Office. The surrounding hills were soon lumpy with breastworks, and massive oaks were felled to clear a line of fire for artillery. "All that the best military skill could suggest to strengthen the position has been done," Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper reported, "and the whole line of defenses on Arlington Heights may be said to be completed and capable of being held against any attacking force."

The attack never materialized, but the war's impact was seen, felt and heard at Arlington in a thousand ways. Union forces denuded the estate's forest and absconded with souvenirs from the mansion. They built cabins and set up a cavalry remount station by the river. The Army also took charge of the newly freed slaves who flocked into Washington after Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation of 1863. When the government was unable to accommodate the former slaves in the capital, where thousands fell sick and died, one of Meigs' officers proposed that they be settled at Arlington, "on the lands recently abandoned by rebel leaders." A sprawling Freedmen's Village of 1,500 sprang to life on the estate, complete with new frame houses, schools, churches and farmlands on which former slaves grew food for the Union's war effort. "One sees more than poetic justice in the fact that its rich lands, so long the domain of the great general of the rebellion, now afford labor and support to hundreds of enfranchised slaves," a visiting journalist would report in the Washington Independent in January 1867.

As the war had heated up in June 1862, Congress passed a law that empowered commissioners to assess and collect taxes on real estate in "insurrectionary districts." The statute was meant not only to raise revenue for the war, but also to punish turncoats like Lee. If the taxes were not paid in person, commissioners were authorized to sell the land.

Authorities levied a tax of $92.07 on the Lees' estate that year. Mary Lee, stuck in Richmond because of the fighting and her deteriorating health, dispatched her cousin Philip R. Fendall to pay the bill. But when Fendall presented himself before the commissioners in Alexandria, they said they would accept money only from Mary Lee herself. Declaring the property in default, they put it up for sale.

The auction took place on January 11, 1864, a day so cold that blocks of ice stopped boat traffic on the Potomac. The sole bid came from the federal government, which offered $26,800, well under the estate's assessed value of $34,100. According to the certificate of sale, Arlington's new owner intended to reserve the property "for Government use, for war, military, charitable and educational purposes."

Appropriating the homestead was perfectly in keeping with the views of Lincoln, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, Gen. William T. Sherman and Montgomery Meigs, all of whom believed in waging total war to bring the rebellion to a speedy conclusion. "Make them so sick of war that generations would pass away before they would again appeal to it," Sherman wrote.

The war, of course, dragged on far longer than anyone expected. By the spring of 1864, Washington's temporary hospitals were overflowing with sick and dying soldiers, who began to fill local cemeteries just as General Lee and the Union commander, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, began their blistering Forty Days' Campaign, exchanging blows from Virginia's Wilderness to Petersburg. The fighting produced some 82,000 casualties in just over a month. Meigs cast about for a new graveyard to accommodate the rising tide of bodies. His eye fell upon Arlington.

The first soldier laid to rest there was Pvt. William Christman, 21, of the 67th Pennsylvania Infantry, who was buried in a plot on Arlington's northeast corner on May 13, 1864. A farmer newly recruited into the Army, Christman never knew a day of combat. Like others who would join him at Arlington, he was felled by disease; he died of peritonitis in Washington's Lincoln General Hospital on May 11. His body was committed to the earth with no flags flying, no bugles playing and no family or chaplain to see him off. A simple pine headboard, painted white with black lettering, identified his grave, like the markers for Pvt. William H. McKinney and other soldiers too poor to be embalmed and sent home for burial. The indigent dead soon filled the Lower Cemetery—a name that described both its physical and social status—across the lane from a graveyard for slaves and freedmen.

The next month, Meigs moved to make official what was already a matter of practice: "I recommend that...the land surrounding the Arlington Mansion, now understood to be the property of the United States, be appropriated as a National Military Cemetery, to be properly enclosed, laid out and carefully preserved for that purpose," he wrote Stanton on June 15, 1864. Meigs proposed devoting 200 acres to the new graveyard. He also suggested that Christman and others recently interred in the Lower Cemetery should be unearthed and reburied closer to Lee's hilltop home. "The grounds about the Mansion are admirably adapted to such a use," he wrote.

Stanton endorsed the quartermaster's recommendation the same day.

Loyalist newspapers applauded the birth of Arlington National Cemetery, one of 13 new graveyards created specifically for those dying in the Civil War. "This and the [Freedmen's Village]...are righteous uses of the estate of the Rebel General Lee," read the Washington Morning Chronicle.

Touring the new national cemetery on the day that Stanton signed his order, Meigs was incensed to see where the graves were being dug. "It was my intention to have begun the interments nearer the mansion," he fumed, "but opposition on the part of officers stationed at Arlington, some of whom...did not like to have the dead buried near them, caused the interments to be begun" in the Lower Cemetery, where Christman and others were buried.

To enforce his orders—and to make Arlington uninhabitable for the Lees—Meigs evicted officers from the mansion, installed a military chaplain and a loyal lieutenant to oversee cemetery operations, and proceeded with new burials, encircling Mrs. Lee's garden with the tombstones of prominent Union officers. The first of these was Capt. Albert H. Packard of the 31st Maine Infantry. Shot in the head during the Battle of the Second Wilderness, Packard had miraculously survived his journey from the Virginia front to Washington's Columbian College Hospital, only to die there. On May 17, 1864, he was laid to rest where Mary Lee had enjoyed reading in warm weather, surrounded by the scent of honeysuckle and jasmine. By the end of 1864, some 40 officers' graves had joined his.

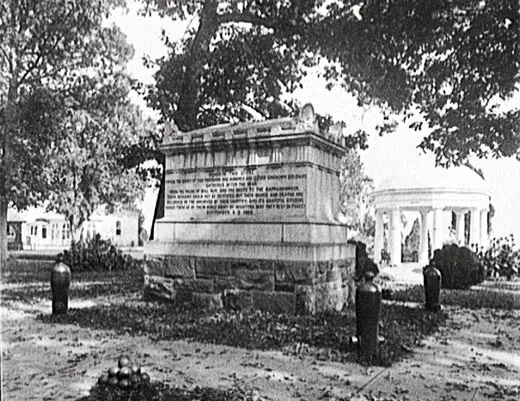

Meigs added others as soon as conditions allowed. He dispatched crews to scour battlefields for unknown soldiers near Washington. Then he excavated a huge pit at the end of Mrs. Lee's garden, filled it with the remains of 2,111 nameless soldiers and raised a sarcophagus in their honor. He understood that by seeding the garden with prominent Union officers and unknown patriots, he would make it politically difficult to disinter these heroes of the Republic at a later date.

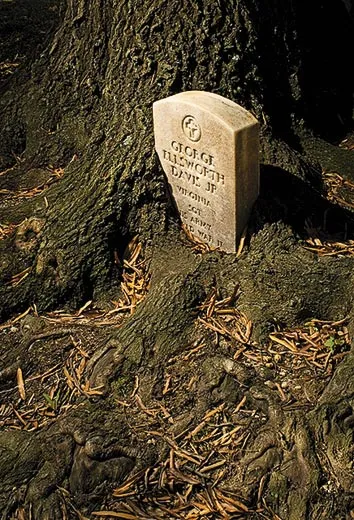

The last autumn of the war produced thousands of new casualties, including Lt. John Rodgers Meigs, one of the quartermaster's four sons. Lieutenant Meigs, 22, was shot on October 3, 1864, while on a scouting mission for Gen. Philip Sheridan in Virginia's Shenandoah Valley. He was returned with solemn honors to Washington, where Lincoln, Stanton and other dignitaries joined his father for the funeral and burial in Georgetown. The loss of his "noble precious son" only deepened Meigs' antipathy toward Robert E. Lee.

"The rebels are all murderers of my son and the sons of hundreds of thousands," Meigs exploded when he learned of Lee's surrender to Grant on April 9, 1865. "Justice seems not satisfied [if] they escape judicial trial & execution... by the government which they have betrayed [&] attacked & whose people loyal & disloyal they have slaughtered." If Lee and other Confederates escaped punishment because of pardons or paroles, Meigs hoped that Congress would at least banish them from American soil.

Lee avoided the spectacle of a trial. Treason charges were filed against him but quietly dropped, almost certainly because his former adversary, Grant, interceded on Lee's behalf with President Andrew Johnson. Settling in Lexington, Virginia, Lee took over as president of Washington College, a struggling little school deep in the Shenandoah Valley, and encouraged old comrades to work for peace.

The Lees would spend the postwar years trying to retake possession of their estate.

Mary Lee felt a growing outrage. "I cannot write with composure on my own cherished Arlington," she wrote to a friend. The graves "are planted up to the very door without any regard to common decency....If justice & law are not utterly extinct in the U.S., I will have it back."

Her husband, however, kept his ambitions for Arlington hidden from all but a few advisers and family members. "I have not taken any steps in the matter," he cautioned a Washington lawyer who offered to take on the Arlington case for free, "under the belief that at present I could accomplish no good." But he encouraged the lawyer to research the case quietly and to coordinate his efforts with Francis L. Smith, Lee's trusted legal adviser in Alexandria. To his elder brother Smith Lee, who had served as an officer in the Confederate navy, the general admitted that he wanted to "regain the possession of A." and particularly "to terminate the burial of the dead which can only be done by its restoration to the family."

To gauge whether this was possible, Smith Lee made a clandestine visit to the old estate in the autumn or winter of 1865. He concluded that the place could be made habitable again if a wall was built to screen the graves from the mansion. But Smith Lee made the mistake of sharing his views with the cemetery superintendent, who dutifully shared them with Meigs, along with the mystery visitor's identity.

While the Lees worked to reclaim Arlington, Meigs urged Edwin Stanton in early 1866 to make sure the government had sound title to the cemetery. The land had been consecrated by the remains buried there and could not be given back to the Lees, he insisted, striking a refrain he would repeat in the years ahead. Yet the Lees clung to the hope that Arlington might be returned to the family—if not to Mrs. Lee, then to one of their sons. The former general was quietly pursuing this objective when he met with his lawyers for the last time, in July 1870. "The prospect does not look promising," he reported to Mary. The question of Arlington's ownership was still unresolved when Lee died, at 63, in Lexington, on October 12, 1870.

His widow continued to obsess over the loss of her home. Within weeks, Mary Lee petitioned Congress to examine the federal claim to Arlington and estimate the costs of removing the bodies buried there.

Her proposal was bitterly protested on the Senate floor and defeated, 54 to 4. It was a disaster for Mary Lee, but the debate helped to elevate Arlington's status: no longer a potter's field created in the desperation of wartime, the cemetery was becoming something far grander, a place senators referred to as hallowed ground, a shrine for "the sacred dead," "the patriot dead," "the heroic dead" and "patriotic graves."

The plantation the Lees had known became less recognizable each year. Many original residents of Freedmen's Village stayed on after the war, raising children and grandchildren in the little houses the Army had built for them. Meigs stayed on, too, serving as quartermaster general for two decades, shaping the look of the cemetery. He raised a Greek-style Temple of Fame to George Washington and to distinguished Civil War generals by Mrs. Lee's garden, established a wisteria-draped amphitheater large enough to accommodate 5,000 people for ceremonies and even prescribed new plantings for the garden's borders (elephant ears and canna). He watched the officers' section of the cemetery sprout enormous tombstones typical of the Gilded Age. And he erected a massive red arch at the cemetery's entrance to honor Gen. George B. McClellan, one of the Civil War's most popular—and least effective—officers. As was his habit, Meigs included his name on the arch; it was chiseled into the entrance column and lettered in gold. Today, it is one of the first things a visitor sees when approaching the cemetery from the east.

While Meigs built, Mary Lee managed a farewell visit to Arlington in June 1873. Accompanied by a friend, she rode in a carriage for three hours through a landscape utterly transformed, filled with old memories and new graves. "My visit produced one good effect," she wrote later that week. "The change is so entire that I have not the yearning to go back there & shall be more content to resign all my right in it." She died in Lexington five months later, at age 65.

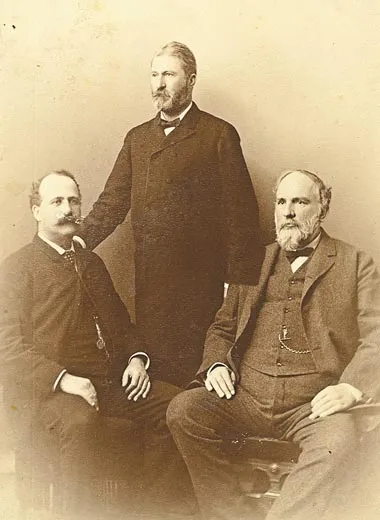

With her death, her hopes for Arlington lived on in her eldest son, George Washington Custis Lee, known as Custis. For him, regaining the estate was a matter of both filial obligation and self-interest: he had no inheritance beyond the Arlington property.

On April 6, 1874, within months of his mother's funeral, Custis went to Congress with a new petition. Avoiding her inflammatory suggestion that Arlington be cleared of graves, he asked instead for an admission that the property had been taken unlawfully and requested compensation for it. He argued that his mother's good-faith attempt to pay the "insurrectionary tax" of $92.07 on Arlington was the same as if she had paid it.

While the petition languished for months in the Senate Judiciary Committee, Meigs worried that it would "interfere with the United States' tenure of this National Cemetery—a result to be avoided by all just means." He need not have worried. A few weeks later, the petition died quietly in committee, attended by no debate and scant notice.

Custis Lee might have given up then and there if not for signs that the hard feelings between North and South were beginning to soften. Rutherford B. Hayes, a Union veteran elected on the promise of healing scars from the Civil War, was sworn in as president in March 1877.

Hayes hardly had time to unpack his bags before Custis Lee revived the campaign for Arlington—this time in court.

Asserting ownership of the property, Lee asked the Circuit Court of Alexandria, Virginia, to evict all trespassers occupying it as a result of the 1864 auction. As soon as U.S. Attorney General Charles Devens heard about the suit, he asked that the case be shifted to federal court, where he felt the government would get a fairer hearing. In July 1877, the matter landed in the lap of Judge Robert W. Hughes of the U.S. Circuit Court for the Eastern District of Virginia. Hughes, a lawyer and newspaper editor, had been appointed to the bench by President Grant.

After months of legal maneuvering and arguments, Hughes ordered a jury trial. Custis Lee's team of lawyers was headed by Francis L. Smith, the Alexandrian who had strategized with Lee's father years before. Their argument turned upon the legality of the 1864 tax sale. After a six-day trial, a jury found for Lee on January 30, 1879: by requiring the "insurrectionary tax" to be paid in person, the government had deprived Custis Lee of his property without due process of law. "The impolicy of such a provision of law is as obvious to me as its unconstitutionality," Hughes wrote. "Its evil would be liable to fall not only upon disloyal but upon the most loyal citizens. A severe illness lasting only ninety or a hundred days would subject the owner of land to the irreclaimable loss of its possession."

The government appealed the verdict to the Supreme Court—which ruled for Lee again. On December 4, 1882, Associate Justice Samuel Freeman Miller, a Kentucky native appointed by President Lincoln, wrote for the 5 to 4 majority, holding that the 1864 tax sale had been unconstitutional and was therefore invalid.

The Lees had retaken Arlington.

This left few options for the federal government, which was now technically trespassing on private property. It could abandon an Army fort on the grounds, roust the residents of Freedmen's Village, disinter almost 20,000 graves and vacate the property. Or it could buy the estate from Custis Lee—if he was willing to sell it.

He was. Both sides agreed on a price of $150,000, the property's fair market value. Congress quickly appropriated the funds. Lee signed papers conveying the title on March 31, 1883, which placed federal ownership of Arlington beyond dispute. The man who formally accepted title to the property for the government was none other than Robert Todd Lincoln, secretary of war and son of the president so often bedeviled by Custis Lee's father. If the sons of such adversaries could bury past arguments, perhaps there was hope for national reunion.

The same year the Supreme Court ruled in Custis Lee's favor, Montgomery Meigs, having reached the mandatory retirement age of 65, was forced out of the quartermaster's job. He would remain active in Washington for another decade, designing and overseeing construction of the Pension Building, serving as a Regent of the Smithsonian Institution and as a member of the National Academy of Sciences. He was a frequent visitor to Arlington, where he had buried his wife, Louisa, in 1879. The burials of other family members followed—among them his father, numerous in-laws and his son, John, reburied from Georgetown. Their graves, anchoring Row 1, Section 1 of the cemetery, far outnumbered those of any Lee relatives on the estate.

Meigs joined his family in January 1892, age 75, after a brief bout with the flu. He made the final journey from Washington in fine style, accompanied by an Army band, flying flags and an honor guard of 150 soldiers decked out in their best uniforms. His flag-draped caisson rattled across the river, up the long slope to Arlington and across the meadow of tombstones he had so assiduously cultivated. With muffled drums marking time and guidons snapping in the chill wind, the funeral procession passed Mary Lee's garden and came to a halt on Meigs Drive. The rifles barked their last salute, "Taps" sounded over the tawny hills and soldiers eased Montgomery C. Meigs into the ground at the heart of the cemetery he created.

Adapted from On Hallowed Ground, by Robert M. Poole. © 2009 Robert M. Poole. Published by Walker & Company. Reproduced with permission.