The Freedom Riders, Then and Now

Fighting racial segregation in the South, these activists were beaten and arrested. Where are they now, nearly fifty years later?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/mob-attacks-bus-Alabama-631.jpg)

On Sunday, May 14, 1961—Mother's Day—scores of angry white people blocked a Greyhound bus carrying black and white passengers through rural Alabama. The attackers pelted the vehicle with rocks and bricks, slashed tires, smashed windows with pipes and axes and lobbed a firebomb through a broken window. As smoke and flames filled the bus, the mob barricaded the door. "Burn them alive," somebody cried out. "Fry the goddamn niggers." An exploding fuel tank and warning shots from arriving state troopers forced the rabble back and allowed the riders to escape the inferno. Even then some were pummeled with baseball bats as they fled.

A few hours later, black and white passengers on a Trailways bus were beaten bloody after they entered whites-only waiting rooms and restaurants at bus terminals in Birmingham and Anniston, Alabama.

The bus passengers assaulted that day were Freedom Riders, among the first of more than 400 volunteers who traveled throughout the South on regularly scheduled buses for seven months in 1961 to test a 1960 Supreme Court decision that declared segregated facilities for interstate passengers illegal.

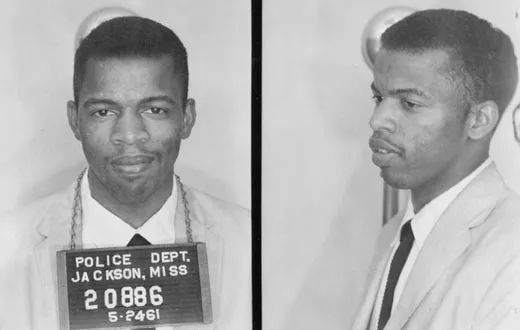

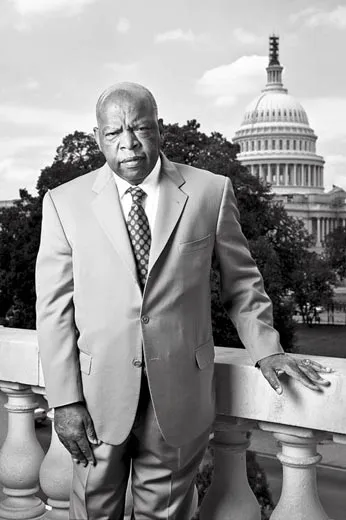

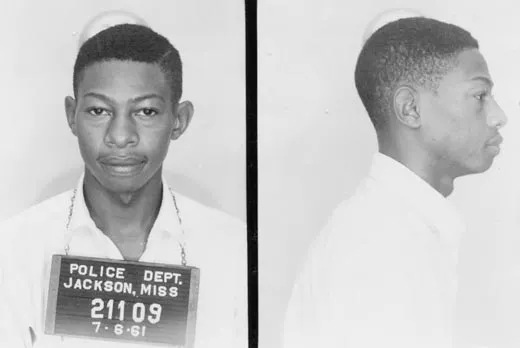

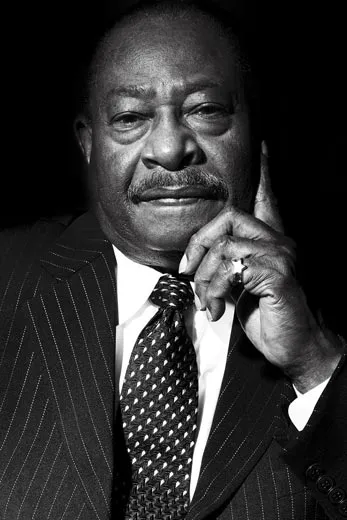

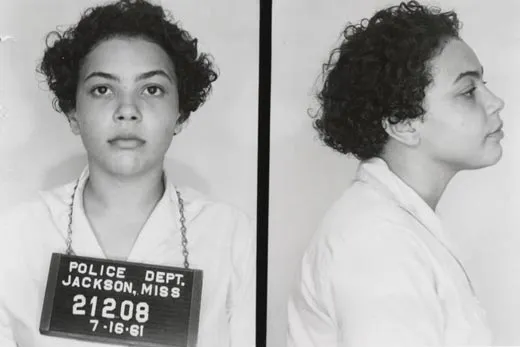

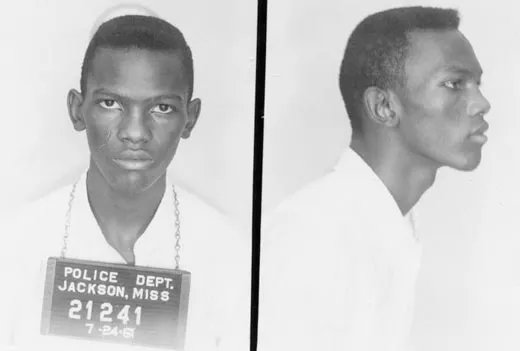

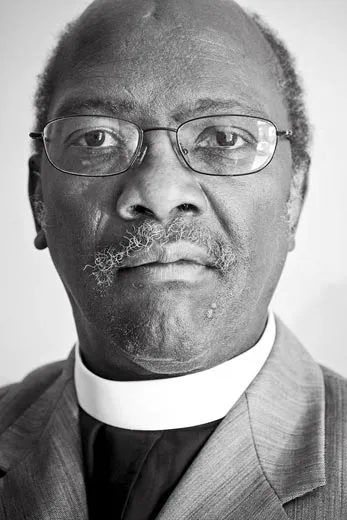

After news stories and photographs of the burning bus and bloody attacks sped around the country, many more people came forward to risk their lives and challenge the racial status quo. Now Eric Etheridge, a veteran magazine editor, provides a visceral tribute to those road warriors in Breach of Peace: Portraits of the 1961 Mississippi Freedom Riders. The book, a collection of Etheridge's recent portraits of 80 Freedom Riders juxtaposed with mug shots from their arrests in 1961, includes interviews with the activists re-flecting on their experiences.

Etheridge, who grew up in Carthage, Mississippi, focuses on Freedom Riders who boarded buses to Jackson, Mississippi, from late May to mid-September 1961. He was just 4 years old at the time and unaware of the seismic racial upheaval taking place around him. But he well remembers using one entrance to his doctor's office while African-Americans used another, and sitting in the orchestra of his local movie theater while blacks sat in the balcony.

"Looking back," Etheridge says, "I can identify with what the white South African photographer Jillian Edelstein has said: 'Growing up white in apartheid South Africa entitled one to massive and instant privilege.'"

A few years ago, Etheridge, who lives in New York City and has worked for Rolling Stone and Harper's, began looking for a project to engage his budding photographic skills. During a visit with his parents in Jackson in 2003, he was reminded that a lawsuit had forced the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission, an agency created in 1956 to resist desegregation, to open its archives. The agency files, put online in 2002, included more than 300 arrest photographs of Freedom Riders."The police camera caught something special," Etheridge says, adding that the collection is "an amazing addition to the visual history of the civil rights movement." Unwittingly, the segregationist commission had created an indelible homage to the activist riders.

Nearly 75 percent of them were between 18 and 30 years old. About half were black; a quarter, women. Their mug-shot expressions hint at their resolve, defiance, pride, vulnerability and fear. "I was captivated by these images and wanted to bring them to a wider audience," Etheridge writes. "I wanted to find the riders today, to look into their faces and photograph them again." Using the Internet and information in the arrest files, he tracked riders down, then called them cold. "My best icebreaker was: 'I have your mug shot from 1961. Have you ever seen it?' Even people who are prone to be cautious were tickled to even think that it still existed."

Most of the riders were college students; many, such as the Episcopal clergymen and contingents of Yale divinity students, had religious affiliations. Some were active in civil rights groups like the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), which initiated the Freedom Rides and was founded in 1942 on Mahatma Gandhi's principle of nonviolent protest. The goal of the rides, CORE director James Farmer said as he launched the campaign, was "to create a crisis so that the federal government would be compelled to enforce the law."

The volunteers, from 40 states, received training in nonviolence tactics. Those who could not refrain from striking back when pushed, hit, spit on or doused with liquids while racial epithets rang in their ears were rejected.

As soon as he heard the call for riders, Robert Singleton remembers, he "was fired up and ready to go." He and his wife, Helen, had both been active in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and they took 12 volunteers with them from California. "The spirit that permeated the air at that time was not unlike the feeling Barack Obama has rekindled among the youth of today," says Singleton, now 73 and an economics professor at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles.

Peter Ackerberg, a lawyer who now lives in Minneapolis, said that while he'd always talked a "big radical game," he had never acted on his convictions. "What am I going to tell my children when they ask me about this time?" he recalled thinking. Boarding a bus in Montgomery, Alabama, "I was pretty scared," he told Etheridge. "The black guys and girls were singing....They were so spirited and so unafraid. They were really prepared to risk their lives." Today, Ackerberg recalls acquiescing and saying "sir" to a jail official who was "pounding a blackjack." Soon after, "I could hear the blackjack strike [rider C.T. Vivian's] head and him shrieking; I don't think he ever said 'sir.'"

John Lewis, then 21 and already a veteran of sit-ins to desegregate lunch counters in Nashville, was the first Freedom Rider to be assaulted. While trying to enter a whites-only waiting room in Rock Hill, South Carolina, two men set upon him, battering his face and kicking him in the ribs. Less than two weeks later, he joined a ride bound for Jackson. "We were determined not to let any act of violence keep us from our goal," Lewis, a Georgia congressman since 1987 and a celebrated civil rights figure, said recently. "We knew our lives could be threatened, but we had made up our minds not to turn back."

As riders poured into the South, National Guardsmen were assigned to some buses to prevent violence. When activists arrived at the Jackson bus depot, police arrested blacks who refused to heed orders to stay out of white restrooms or vacate the white waiting room. And whites were arrested if they used "colored" facilities. Officials charged the riders with breach of peace, rather than breaking segregation laws. Freedom Riders responded with a strategy they called "jail, no bail"—a deliberate effort to clog the penal facilities. Most of the 300 riders in Jackson would endure six weeks in sweltering jail or prison cells rife with mice, insects, soiled mattresses and open toilets.

"The dehumanizing process started as soon as we got there," said Hank Thomas, a Marriott hotel franchise owner in Atlanta, who was then a sophomore at Howard University in Washington, D.C. "We were told to strip naked and then walked down this long corridor.... I'll never forget [CORE director] Jim Farmer, a very dignified man ...walking down this long corridor naked...that is dehumanizing. And that was the whole point."

Jean Thompson, then a 19-year-old CORE worker, said she was one of the riders slapped by a penal official for failing to call him "sir." An FBI investigation into the incident concluded that "no one was beaten," she told Etheridge. "That said a lot to me about what actually happens in this country. It was eye-opening." When prisoners were transferred from one facility to another, unexplained stops on remote dirt roads or the sight of curious onlookers peering into the transport trucks heightened fears. "We imagined every horror including an ambush by the KKK," rider Carol Silver told Etheridge. To keep up their spirits, the prisoners sang freedom songs.

None of the riders Etheridge spoke with expressed regrets, even though some would be entangled for years in legal appeals that went all the way to the Supreme Court (which issued a ruling in 1965 that led to a reversal of the breach of peace convictions). "It's the right thing to do, to oppose an oppressive state where wrongs are being done to people," said William Leons, a University of Toledo professor of anthropology whose father had been killed in an Austrian concentration camp and whose mother hid refugees during World War II. "I was aware very much of my parents' involvement in the Nazi resistance," he said of his 39-day incarceration as a rider. "[I was] doing what they would have done."

More than two dozen of the riders Etheridge interviewed went on to become teachers or professors, and there are eight ministers as well as lawyers, Peace Corps workers, journalists and politicians. Like Lewis, Bob Filner, of California, is a congressman. And few former Freedom Riders still practice civil disobedience. Joan Pleune, 70, of New York City, is a member of the Granny Peace Brigade; she was arrested two years ago at an anti-Iraq War protest in Washington, D.C. while "reading the names of the war dead," she says. Theresa Walker, 80, was arrested in New York City in 2000 during a protest over the police killing there the year before of Amadou Diallo, an unarmed immigrant from Guinea.

Though the Freedom Rides dramatically demonstrated that some Southern states were ignoring the U.S. Supreme Court's mandate to desegregate bus terminals, it would take a petition from U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy to spur the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) to issue tough new regulations, backed by fines up to $500, that would eventually end segregated bus facilities. Even after the order went into effect, on November 1, 1961, hard-core segregation persisted; still, the "white" and "colored" signs in bus stations across the South be- gan to come down. The New York Times, which had earlier criticized the Freedom Riders' "incitement and provocation," acknowledged that they "started the chain of events which resulted in the new I.C.C. order."

The legacy of the rides "could not have been more poetic," says Robert Singleton, who connects those events to the election of Barack Obama as president. Obama was born in August 1961, Singleton notes, just when the riders were languishing in Mississippi jails and prisons, trying to "break the back of segregation for all people, but especially for the children. We put ourselves in harm's way for a child, at the very time he came into this world, who would become our first black president."

Marian Smith Holmes is an associate editor.

Photographer Eric Etheridge maintains a Web site, breachofpeace.com, that publishes information about the Freedom Riders.