Who Was Mary Magdalene?

From the writing of the New Testament to the filming of The Da Vinci Code, her image has been repeatedly conscripted, contorted and contradicted

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/mary-magdalene-penitent-Pedro-de-Moya631.jpg)

The whole history of western civilization is epitomized in the cult of Mary Magdalene. For many centuries the most obsessively revered of saints, this woman became the embodiment of Christian devotion, which was defined as repentance. Yet she was only elusively identified in Scripture, and has thus served as a scrim onto which a succession of fantasies has been projected. In one age after another her image was reinvented, from prostitute to sibyl to mystic to celibate nun to passive helpmeet to feminist icon to the matriarch of divinity’s secret dynasty. How the past is remembered, how sexual desire is domesticated, how men and women negotiate their separate impulses; how power inevitably seeks sanctification, how tradition becomes authoritative, how revolutions are co-opted; how fallibility is reckoned with, and how sweet devotion can be made to serve violent domination—all these cultural questions helped shape the story of the woman who befriended Jesus of Nazareth.

Who was she? From the New Testament, one can conclude that Mary of Magdala (her hometown, a village on the shore of the Sea of Galilee) was a leading figure among those attracted to Jesus. When the men in that company abandoned him at the hour of mortal danger, Mary of Magdala was one of the women who stayed with him, even to the Crucifixion. She was present at the tomb, the first person to whom Jesus appeared after his resurrection and the first to preach the “Good News” of that miracle. These are among the few specific assertions made about Mary Magdalene in the Gospels. From other texts of the early Christian era, it seems that her status as an “apostle,” in the years after Jesus’ death, rivaled even that of Peter. This prominence derived from the intimacy of her relationship with Jesus, which, according to some accounts, had a physical aspect that included kissing. Beginning with the threads of these few statements in the earliest Christian records, dating to the first through third centuries, an elaborate tapestry was woven, leading to a portrait of St. Mary Magdalene in which the most consequential note—that she was a repentant prostitute—is almost certainly untrue. On that false note hangs the dual use to which her legend has been put ever since: discrediting sexuality in general and disempowering women in particular.

Confusions attached to Mary Magdalene’s character were compounded across time as her image was conscripted into one power struggle after another, and twisted accordingly. In conflicts that defined the Christian Church—over attitudes toward the material world, focused on sexuality; the authority of an all-male clergy; the coming of celibacy; the branding of theological diversity as heresy; the sublimations of courtly love; the unleashing of “chivalrous” violence; the marketing of sainthood, whether in the time of Constantine, the Counter-Reformation, the Romantic era, or the Industrial Age—through all of these, reinventions of Mary Magdalene played their role. Her recent reemergence in a novel and film as the secret wife of Jesus and the mother of his fate-burdened daughter shows that the conscripting and twisting are still going on.

But, in truth, the confusion starts with the Gospels themselves.

In the gospels several women come into the story of Jesus with great energy, including erotic energy. There are several Marys—not least, of course, Mary the mother of Jesus. But there is Mary of Bethany, sister of Martha and Lazarus. There is Mary the mother of James and Joseph, and Mary the wife of Clopas. Equally important, there are three unnamed women who are expressly identified as sexual sinners—the woman with a “bad name” who wipes Jesus’ feet with ointment as a signal of repentance, a Samaritan woman whom Jesus meets at a well and an adulteress whom Pharisees haul before Jesus to see if he will condemn her. The first thing to do in unraveling the tapestry of Mary Magdalene is to tease out the threads that properly belong to these other women. Some of these threads are themselves quite knotted.

It will help to remember how the story that includes them all came to be written. The four Gospels are not eyewitness accounts. They were written 35 to 65 years after Jesus’ death, a jelling of separate oral traditions that had taken form in dispersed Christian communities. Jesus died in about the year a.d. 30. The Gospels of Mark, Matthew and Luke date to about 65 to 85, and have sources and themes in common. The Gospel of John was composed around 90 to 95 and is distinct. So when we read about Mary Magdalene in each of the Gospels, as when we read about Jesus, what we are getting is not history but memory—memory shaped by time, by shades of emphasis and by efforts to make distinctive theological points. And already, even in that early period—as is evident when the varied accounts are measured against each other—the memory is blurred.

Regarding Mary of Magdala, the confusion begins in the eighth chapter of Luke:

Now after this [Jesus] made his way through towns and villages preaching, and proclaiming the Good News of the kingdom of God. With him went the Twelve, as well as certain women who had been cured of evil spirits and ailments: Mary surnamed the Magdalene, from whom seven demons had gone out, Joanna the wife of Herod’s steward Chuza, Susanna, and several others who provided for them out of their own resources.

Two things of note are implied in this passage. First, these women “provided for” Jesus and the Twelve, which suggests that the women were well-to-do, respectable figures. (It is possible this was an attribution, to Jesus’ time, of a role prosperous women played some years later.) Second, they all had been cured of something, including Mary Magdalene. The “seven demons,” as applied to her, indicates an ailment (not necessarily possession) of a certain severity. Soon enough, as the blurring work of memory continued, and then as the written Gospel was read by Gentiles unfamiliar with such coded language, those “demons” would be taken as a sign of a moral infirmity.

This otherwise innocuous reference to Mary Magdalene takes on a kind of radioactive narrative energy because of what immediately precedes it at the end of the seventh chapter, an anecdote of stupendous power:

One of the Pharisees invited [Jesus] to a meal. When he arrived at the Pharisee’s house and took his place at table, a woman came in, who had a bad name in the town. She had heard he was dining with the Pharisee and had brought with her an alabaster jar of ointment. She waited behind him at his feet, weeping, and her tears fell on his feet, and she wiped them away with her hair; then she covered his feet with kisses and anointed them with the ointment.

When the Pharisee who had invited him saw this, he said to himself, “If this man were a prophet, he would know who this woman is that is touching him and what a bad name she has.”

But Jesus refuses to condemn her, or even to deflect her gesture. Indeed, he recognizes it as a sign that “her many sins must have been forgiven her, or she would not have shown such great love.” “Your faith has saved you,” Jesus tells her. “Go in peace.”

This story of the woman with the bad name, the alabaster jar, the loose hair, the “many sins,” the stricken conscience, the ointment, the rubbing of feet and the kissing would, over time, become the dramatic high point of the story of Mary Magdalene. The scene would be explicitly attached to her, and rendered again and again by the greatest Christian artists. But even a casual reading of this text, however charged its juxtaposition with the subsequent verses, suggests that the two women have nothing to do with each other—that the weeping anointer is no more connected to Mary of Magdala than she is to Joanna or Susanna.

Other verses in other Gospels only add to the complexity. Matthew gives an account of the same incident, for example, but to make a different point and with a crucial detail added:

Jesus was at Bethany in the house of Simon the leper, when a woman came to him with an alabaster jar of the most expensive ointment, and poured it on his head as he was at table. When they saw this, the disciples were indignant. “Why this waste?” they said. “This could have been sold at a high price and the money given to the poor.” Jesus noticed this. “Why are you upsetting the woman?” he said to them.... “When she poured this ointment on my body, she did it to prepare me for burial. I tell you solemnly, wherever in all the world this Good News is proclaimed, what she has done will be told also, in remembrance of her.”

This passage shows what Scripture scholars commonly call the “telephone game” character of the oral tradition from which the Gospels grew. Instead of Luke’s Pharisee, whose name is Simon, we find in Matthew “Simon the leper.” Most tellingly, this anointing is specifically referred to as the traditional rubbing of a corpse with oil, so the act is an explicit foreshadowing of Jesus’ death. In Matthew, and in Mark, the story of the unnamed woman puts her acceptance of Jesus’ coming death in glorious contrast to the (male) disciples’ refusal to take Jesus’ predictions of his death seriously. But in other passages, Mary Magdalene is associated by name with the burial of Jesus, which helps explain why it was easy to confuse this anonymous woman with her.

Indeed, with this incident both Matthew’s and Mark’s narratives begin the move toward the climax of the Crucifixion, because one of the disciples—“the man called Judas”—goes, in the very next verse, to the chief priests to betray Jesus.

In the passages about the anointings, the woman is identified by the “alabaster jar,” but in Luke, with no reference to the death ritual, there are clear erotic overtones; a man of that time was to see a woman’s loosened hair only in the intimacy of the bedroom. The offense taken by witnesses in Luke concerns sex, while in Matthew and Mark it concerns money. And, in Luke, the woman’s tears, together with Jesus’ words, define the encounter as one of abject repentance.

But the complications mount. Matthew and Mark say the anointing incident occurred at Bethany, a detail that echoes in the Gospel of John, which has yet another Mary, the sister of Martha and Lazarus, and yet another anointing story:

Six days before the Passover, Jesus went to Bethany, where Lazarus was, whom he had raised from the dead. They gave a dinner for him there; Martha waited on them and Lazarus was among those at table. Mary brought in a pound of very costly ointment, pure nard, and with it anointed the feet of Jesus, wiping them with her hair.

Judas objects in the name of the poor, and once more Jesus is shown defending the woman. “Leave her alone; she had to keep this scent for the day of my burial,” he says. “You have the poor with you always, you will not always have me.”

As before, the anointing foreshadows the Crucifixion. There is also resentment at the waste of a luxury good, so death and money define the content of the encounter. But the loose hair implies the erotic as well.

The death of Jesus on Golgotha, where Mary Magdalene is expressly identified as one of the women who refused to leave him, leads to what is by far the most important affirmation about her. All four Gospels (and another early Christian text, the Gospel of Peter) explicitly name her as present at the tomb, and in John she is the first witness to the resurrection of Jesus. This—not repentance, not sexual renunciation—is her greatest claim. Unlike the men who scattered and ran, who lost faith, who betrayed Jesus, the women stayed. (Even while Christian memory glorifies this act of loyalty, its historical context may have been less noble: the men in Jesus’ company were far more likely to have been arrested than the women.) And chief among them was Mary Magdalene. The Gospel of John puts the story poignantly:

It was very early on the first day of the week and still dark, when Mary of Magdala came to the tomb. She saw that the stone had been moved away from the tomb and came running to Simon Peter and the other disciple, the one Jesus loved. “They have taken the Lord out of the tomb,” she said, “and we don’t know where they have put him.”

Peter and the others rush to the tomb to see for themselves, then disperse again.

Meanwhile Mary stayed outside near the tomb, weeping. Then, still weeping, she stooped to look inside, and saw two angels in white sitting where the body of Jesus had been, one at the head, the other at the feet. They said, “Woman, why are you weeping?” “They have taken my Lord away,” she replied, “and I don’t know where they have put him.” As she said this she turned around and saw Jesus standing there, though she did not recognize him. Jesus said, “Woman, why are you weeping? Who are you looking for?” Supposing him to be the gardener, she said, “Sir, if you have taken him away, tell me where you have put him, and I will go and remove him.” Jesus said, “Mary!” She knew him then and said to him in Hebrew, “Rabbuni!”—which means Master. Jesus said to her, “Do not cling to me, because I have not yet ascended to...my Father and your Father, to my God and your God.” So Mary of Magdala went and told the disciples that she had seen the Lord and that he had said these things to her.

As the story of Jesus was told and told again in those first decades, narrative adjustments in event and character were inevitable, and confusion of one with the other was a mark of the way the Gospels were handed on. Most Christians were illiterate; they received their traditions through a complex work of memory and interpretation, not history, that led only eventually to texts. Once the sacred texts were authoritatively set, the exegetes who interpreted them could make careful distinctions, keeping the roster of women separate, but common preachers were less careful. The telling of anecdotes was essential to them, and so alterations were certain to occur.

The multiplicity of the Marys by itself was enough to mix things up—as were the various accounts of anointing, which in one place is the act of a loose-haired prostitute, in another of a modest stranger preparing Jesus for the tomb, and in yet another of a beloved friend named Mary. Women who weep, albeit in a range of circumstances, emerged as a motif. As with every narrative, erotic details loomed large, especially because Jesus’ attitude toward women with sexual histories was one of the things that set him apart from other teachers of the time. Not only was Jesus remembered as treating women with respect, as equals in his circle; not only did he refuse to reduce them to their sexuality; Jesus was expressly portrayed as a man who loved women, and whom women loved.

The climax of that theme takes place in the garden of the tomb, with that one word of address, “Mary!” It was enough to make her recognize him, and her response is clear from what he says then: “Do not cling to me.” Whatever it was before, bodily expression between Jesus and Mary of Magdala must be different now.

Out of these disparate threads—the various female figures, the ointment, the hair, the weeping, the unparalleled intimacy at the tomb—a new character was created for Mary Magdalene. Out of the threads, that is, a tapestry was woven—a single narrative line. Across time, this Mary went from being an important disciple whose superior status depended on the confidence Jesus himself had invested in her, to a repentant whore whose status depended on the erotic charge of her history and the misery of her stricken conscience. In part, this development arose out of a natural impulse to see the fragments of Scripture whole, to make a disjointed narrative adhere, with separate choices and consequences being tied to each other in one drama. It is as if Aristotle’s principle of unity, given in Poetics, was imposed after the fact on the foundational texts of Christianity.

Thus, for example, out of discrete episodes in the Gospel narratives, some readers would even create a far more unified—more satisfying—legend according to which Mary of Magdala was the unnamed woman being married at the wedding feast of Cana, where Jesus famously turned water into wine. Her spouse, in this telling, was John, whom Jesus immediately recruited to be one of the Twelve. When John went off from Cana with the Lord, leaving his new wife behind, she collapsed in a fit of loneliness and jealousy and began to sell herself to other men. She next appeared in the narrative as the by then notorious adulteress whom the Pharisees thrust before Jesus. When Jesus refused to condemn her, she saw the error of her ways. Consequently, she went and got her precious ointment and spread it on his feet, weeping in sorrow. From then on she followed him, in chastity and devotion, her love forever unconsummated—“Do not cling to me!”—and more intense for being so.

Such a woman lives on as Mary Magdalene in Western Christianity and in the secular Western imagination, right down, say, to the rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar, in which Mary Magdalene sings, “I don’t know how to love him...He’s just a man, and I’ve had so many men before...I want him so. I love him so.” The story has timeless appeal, first, because that problem of “how”—whether love should be eros or agape; sensual or spiritual; a matter of longing or consummation—defines the human condition. What makes the conflict universal is the dual experience of sex: the necessary means of reproduction and the madness of passionate encounter. For women, the maternal can seem to be at odds with the erotic, a tension that in men can be reduced to the well-known opposite fantasies of the madonna and the whore. I write as a man, yet it seems to me in women this tension is expressed in attitudes not toward men, but toward femaleness itself. The image of Mary Magdalene gives expression to such tensions, and draws power from them, especially when it is twinned to the image of that other Mary, Jesus’ mother.

Christians may worship the Blessed Virgin, but it is Magdalene with whom they identify. What makes her compelling is that she is not merely the whore in contrast to the Madonna who is the mother of Jesus, but that she combines both figures in herself. Pure by virtue of her repentance, she nevertheless remains a woman with a past. Her conversion, instead of removing her erotic allure, heightens it. The misery of self-accusation, known in one way or another to every human being, finds release in a figure whose abject penitence is the condition of recovery. That she is sorry for having led the willful life of a sex object makes her only more compelling as what might be called a repentance object.

So the invention of the character of Mary Magdalene as repentant prostitute can be seen as having come about because of pressures inhering in the narrative form and in the primordial urge to give expression to the inevitable tensions of sexual restlessness. But neither of these was the main factor in the conversion of Mary Magdalene’s image, from one that challenged men’s misogynist assumptions to one that confirmed them. The main factor in that transformation was, in fact, the manipulation of her image by those very men. The mutation took a long time to accomplish—fully the first 600 years of the Christian era.

Again, it helps to have a chronology in mind, with a focus on the place of women in the Jesus movement. Phase one is the time of Jesus himself, and there is every reason to believe that, according to his teaching and in his circle, women were uniquely empowered as fully equal. In phase two, when the norms and assumptions of the Jesus community were being written down, the equality of women is reflected in the letters of St. Paul (c. 50-60), who names women as full partners—his partners—in the Christian movement, and in the Gospel accounts that give evidence of Jesus’ own attitudes and highlight women whose courage and fidelity stand in marked contrast to the men’s cowardice.

But by phase three—after the Gospels are written, but before the New Testament is defined as such—Jesus’ rejection of the prevailing male dominance was being eroded in the Christian community. The Gospels themselves, written in those several decades after Jesus, can be read to suggest this erosion because of their emphasis on the authority of “the Twelve,” who are all males. (The all-male composition of “the Twelve” is expressly used by the Vatican today to exclude women from ordination.) But in the books of the New Testament, the argument among Christians over the place of women in the community is implicit; it becomes quite explicit in other sacred texts of that early period. Not surprisingly, perhaps, the figure who most embodies the imaginative and theological conflict over the place of women in the “church,” as it had begun to call itself, is Mary Magdalene.

Here, it is useful to recall not only how the New Testament texts were composed, but also how they were selected as a sacred literature. The popular assumption is that the Epistles of Paul and James and the four Gospels, together with the Acts of the Apostles and the Book of Revelation, were pretty much what the early Christian community had by way of foundational writings. These texts, believed to be “inspired by the Holy Spirit,” are regarded as having somehow been conveyed by God to the church, and joined to the previously “inspired” and selected books of the Old Testament to form “the Bible.” But the holy books of Christianity (like the holy books of Judaism, for that matter) were established by a process far more complicated (and human) than that.

The explosive spread of the Good News of Jesus around the Mediterranean world meant that distinct Christian communities were springing up all over the place. There was a lively diversity of belief and practice, which was reflected in the oral traditions and, later, texts those communities drew on. In other words, there were many other texts that could have been included in the “canon” (or list), but weren’t.

It was not until the fourth century that the list of canonized books we now know as the New Testament was established. This amounted to a milestone on the road toward the church’s definition of itself precisely in opposition to Judaism. At the same time, and more subtly, the church was on the way toward understanding itself in opposition to women. Once the church began to enforce the “orthodoxy” of what it deemed Scripture and its doctrinally defined creed, rejected texts—and sometimes the people who prized them, also known as heretics—were destroyed. This was a matter partly of theological dispute—If Jesus was divine, in what way?—and partly of boundary-drawing against Judaism. But there was also an expressly philosophical inquiry at work, as Christians, like their pagan contemporaries, sought to define the relationship between spirit and matter. Among Christians, that argument would soon enough focus on sexuality—and its battleground would be the existential tension between male and female.

As the sacred books were canonized, which texts were excluded, and why? This is the long way around, but we are back to our subject, because one of the most important Christian texts to be found outside the New Testament canon is the so-called Gospel of Mary, a telling of the Jesus-movement story that features Mary Magdalene (decidedly not the woman of the “alabaster jar”) as one of its most powerful leaders. Just as the “canonical” Gospels emerged from communities that associated themselves with the “evangelists,” who may not actually have “written” the texts, this one is named for Mary not because she “wrote” it, but because it emerged from a community that recognized her authority.

Whether through suppression or neglect, the Gospel of Mary was lost in the early period—just as the real Mary Magdalene was beginning to disappear into the writhing misery of a penitent whore, and as women were disappearing from the church’s inner circle. It reappeared in 1896, when a well-preserved, if incomplete, fifth-century copy of a document dating to the second century showed up for sale in Cairo; eventually, other fragments of this text were found. Only slowly through the 20th century did scholars appreciate what the rediscovered Gospel revealed, a process that culminated with the publication in 2003 of The Gospel of Mary of Magdala: Jesus and the First Woman Apostle by Karen L. King.

Although Jesus rejected male dominance, as symbolized in his commissioning of Mary Magdalene to spread word of the Resurrection, male dominance gradually made a powerful comeback within the Jesus movement. But for that to happen, the commissioning of Mary Magdalene had to be reinvented. One sees that very thing under way in the Gospel of Mary.

For example, Peter’s preeminence is elsewhere taken for granted (in Matthew, Jesus says, “You are Peter and on this rock I will build my Church”). Here, he defers to her:

Peter said to Mary, “Sister, we know that the Savior loved you more than all other women. Tell us the words of the Savior that you remember, the things which you know that we don’t because we haven’t heard them.”

Mary responded, “I will teach you about what is hidden from you.” And she began to speak these words to them.

Mary recalls her vision, a kind of esoteric description of the ascent of the soul. The disciples Peter and Andrew are disturbed—not by what she says, but by how she knows it. And now a jealous Peter complains to his fellows, “Did [Jesus] choose her over us?” This draws a sharp rebuke from another apostle, Levi, who says, “If the Savior made her worthy, who are you then for your part to reject her?”

That was the question not only about Mary Magdalene, but about women generally. It should be no surprise, given how successfully the excluding dominance of males established itself in the church of the “Fathers,” that the Gospel of Mary was one of the texts shunted aside in the fourth century. As that text shows, the early image of this Mary as a trusted apostle of Jesus, reflected even in the canonical Gospel texts, proved to be a major obstacle to establishing that male dominance, which is why, whatever other “heretical” problems this gospel posed, that image had to be recast as one of subservience.

Simultaneously, the emphasis on sexuality as the root of all evil served to subordinate all women. The ancient Roman world was rife with flesh-hating spiritualities—Stoicism, Manichaeism, Neoplatonism—and they influenced Christian thinking just as it was jelling into “doctrine.” Thus the need to disempower the figure of Mary Magdalene, so that her succeeding sisters in the church would not compete with men for power, meshed with the impulse to discredit women generally. This was most efficiently done by reducing them to their sexuality, even as sexuality itself was reduced to the realm of temptation, the source of human unworthiness. All of this—from the sexualizing of Mary Magdalene, to the emphatic veneration of the virginity of Mary, the mother of Jesus, to the embrace of celibacy as a clerical ideal, to the marginalizing of female devotion, to the recasting of piety as self-denial, particularly through penitential cults—came to a kind of defining climax at the end of the sixth century. It was then that all the philosophical, theological and ecclesiastical impulses curved back to Scripture, seeking an ultimate imprimatur for what by then was a firm cultural prejudice. It was then that the rails along which the church—and the Western imagination—would run were set.

Pope Gregory I (c. 540-604) was born an aristocrat and served as the prefect of the city of Rome. After his father’s death, he gave everything away and turned his palatial Roman home into a monastery, where he became a lowly monk. It was a time of plague, and indeed the previous pope, Pelagius II, had died of it. When the saintly Gregory was elected to succeed him, he at once emphasized penitential forms of worship as a way of warding off the disease. His pontificate marked a solidifying of discipline and thought, a time of reform and invention both. But it all occurred against the backdrop of the plague, a doom-laden circumstance in which the abjectly repentant Mary Magdalene, warding off the spiritual plague of damnation, could come into her own. With Gregory’s help, she did.

Known as Gregory the Great, he remains one of the most influential figures ever to serve as pope, and in a famous series of sermons on Mary Magdalene, given in Rome in about the year 591, he put the seal on what until then had been a common but unsanctioned reading of her story. With that, Mary’s conflicted image was, in the words of Susan Haskins, author of Mary Magdalene: Myth and Metaphor, “finally settled...for nearly fourteen hundred years.”

It all went back to those Gospel texts. Cutting through the exegetes’ careful distinctions—the various Marys, the sinful women—that had made a bald combining of the figures difficult to sustain, Gregory, standing on his own authority, offered his decoding of the relevant Gospel texts. He established the context within which their meaning was measured from then on:

She whom Luke calls the sinful woman, whom John calls Mary, we believe to be the Mary from whom seven devils were ejected according to Mark. And what did these seven devils signify, if not all the vices?

There it was—the woman of the “alabaster jar” named by the pope himself as Mary of Magdala. He defined her:

It is clear, brothers, that the woman previously used the unguent to perfume her flesh in forbidden acts. What she therefore displayed more scandalously, she was now offering to God in a more praiseworthy manner. She had coveted with earthly eyes, but now through penitence these are consumed with tears. She displayed her hair to set off her face, but now her hair dries her tears. She had spoken proud things with her mouth, but in kissing the Lord’s feet, she now planted her mouth on the Redeemer’s feet. For every delight, therefore, she had had in herself, she now immolated herself. She turned the mass of her crimes to virtues, in order to serve God entirely in penance.

The address “brothers” is the clue. Through the Middle Ages and the Counter-Reformation, into the modern period and against the Enlightenment, monks and priests would read Gregory’s words, and through them they would read the Gospels’ texts themselves. Chivalrous knights, nuns establishing houses for unwed mothers, courtly lovers, desperate sinners, frustrated celibates and an endless succession of preachers would treat Gregory’s reading as literally the gospel truth. Holy Writ, having recast what had actually taken place in the lifetime of Jesus, was itself recast.

The men of the church who benefited from the recasting, forever spared the presence of females in their sanctuaries, would not know that this was what had happened. Having created a myth, they would not remember that it was mythical. Their Mary Magdalene—no fiction, no composite, no betrayal of a once venerated woman—became the only Mary Magdalene that had ever existed.

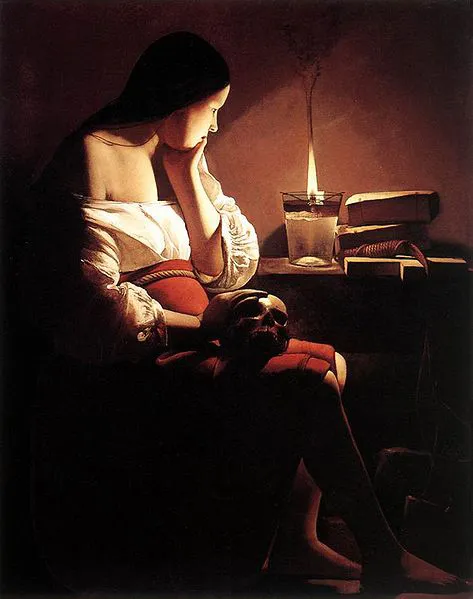

This obliteration of the textual distinctions served to evoke an ideal of virtue that drew its heat from being a celibate’s vision, conjured for celibates. Gregory the Great’s overly particular interest in the fallen woman’s past—what that oil had been used for, how that hair had been displayed, that mouth—brought into the center of church piety a vaguely prurient energy that would thrive under the licensing sponsorship of one of the church’s most revered reforming popes. Eventually, Magdalene, as a denuded object of Renaissance and Baroque painterly preoccupation, became a figure of nothing less than holy pornography, guaranteeing the ever-lustful harlot—if lustful now for the ecstasy of holiness—a permanent place in the Catholic imagination.

Thus Mary of Magdala, who began as a powerful woman at Jesus’ side, “became,” in Haskins’ summary, “the redeemed whore and Christianity’s model of repentance, a manageable, controllable figure, and effective weapon and instrument of propaganda against her own sex.” There were reasons of narrative form for which this happened. There was a harnessing of sexual restlessness to this image. There was the humane appeal of a story that emphasized the possibility of forgiveness and redemption. But what most drove the anti-sexual sexualizing of Mary Magdalene was the male need to dominate women. In the Catholic Church, as elsewhere, that need is still being met.