Faces of War

Amid the horrors of World War I, a corps of artists brought hope to soldiers disfigured in the trenches

Wounded tommies facetiously called it "The Tin Noses Shop." Located within the 3rd London General Hospital, its proper name was the "Masks for Facial Disfigurement Department"; either way, it represented one of the many acts of desperate improvisation borne of the Great War, which had overwhelmed all conventional strategies for dealing with trauma to body, mind and soul. On every front—political, economic, technological, social, spiritual—World War I was changing Europe forever, while claiming the lives of 8 million of her fighting men and wounding 21 million more.

The large-caliber guns of artillery warfare with their power to atomize bodies into unrecoverable fragments and the mangling, deadly fallout of shrapnel had made clear, at the war's outset, that mankind's military technology wildly outpaced its medical: "Every fracture in this war is a huge open wound," one American doctor reported, "with a not merely broken but shattered bone at the bottom of it." The very nature of trench warfare, moreover, proved diabolically conducive to facial injuries: "[T]he...soldiers failed to understand the menace of the machine gun," recalled Dr. Fred Albee, an American surgeon working in France. "They seemed to think they could pop their heads up over a trench and move quickly enough to dodge the hail of bullets."

Writing in the 1950s, Sir Harold Gillies, a pioneer in the art of facial reconstruction and modern plastic surgery, recalled his war service: "Unlike the student of today, who is weaned on small scar excisions and graduates to harelips, we were suddenly asked to produce half a face." A New Zealander by birth, Gillies was 32 and working as a surgeon in London when the war began, but he left shortly afterward to serve in field ambulances in Belgium and France. In Paris, the opportunity to observe a celebrated facial surgeon at work, together with the field experience that had revealed the shocking physical toll of this new war, led to his determination to specialize in facial reconstruction. Plastic surgery, which aims to restore both function and form to deformities, was, at the war's outset, crudely practiced, with little real attention given to aesthetics. Gillies, working with artists who created likenesses and sculptures of what the men had looked like before their injuries, strove to restore, as much as possible, a mutilated man's original face. Kathleen Scott, a noted sculptress and the widow of Capt. Robert Falcon Scott of Antarctica fame, volunteered to help Gillies, declaring with characteristic aplomb that the "men without noses are very beautiful, like antique marbles."

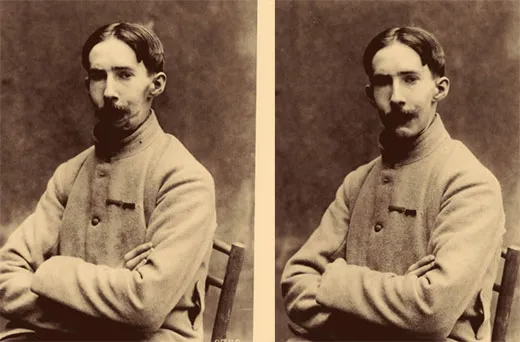

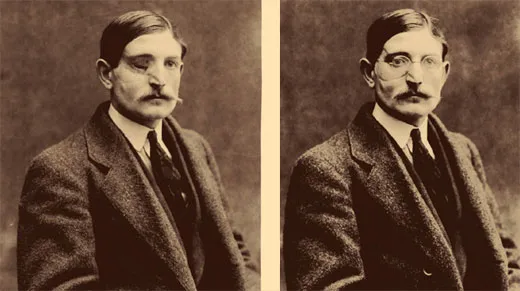

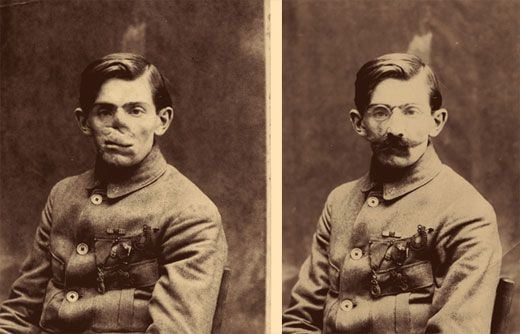

While pioneering work in skin grafting had been done in Germany and the Soviet Union, it was Gillies who refined and then mass-produced critical techniques, many of which are still important to modern plastic surgery: on a single day in early July 1916, following the first engagement of the Battle of the Somme—a day for which the London Times casualty list covered not columns, but pages—Gillies and his colleagues were sent some 2,000 patients. The clinically honest before-and-after photographs published by Gillies shortly after the war in his landmark Plastic Surgery of the Face reveal how remarkably—at times almost unimaginably—successful he and his team could be; but the gallery of seamed and shattered faces, with their brave patchwork of missing parts, also demonstrates the surgeons' limitations. It was for those soldiers—too disfigured to qualify for before-and-after documentation—that the Masks for Facial Disfigurement Department had been established.

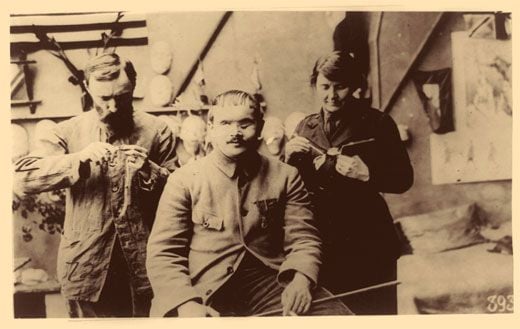

"My work begins where the work of the surgeon is completed," said Francis Derwent Wood, the program's founder. Born in England's Lake District in 1871, of an American father and British mother, Wood had been educated in Switzerland and Germany, as well as England. Following his family's return to England, he trained at various art institutes, cultivating a talent for sculpture he had exhibited as a youth. Too old for active duty when war broke out, he had enlisted, at age 44, as a private in the Royal Army Medical Corps. Upon being assigned as an orderly to the 3rd London General Hospital, he at first performed the usual "errand-boy-housewife" chores. Eventually, however, he took upon himself the task of devising sophisticated splints for patients, and the realization that his abilities as an artist could be medically useful inspired him to construct masks for the irreparably facially disfigured. His new metallic masks, lightweight and more permanent than the rubber prosthetics previously issued, were custom designed to bear the prewar portrait of each wearer. Within the surgical and convalescent wards, it was grimly accepted that facial disfigurement was the most traumatic of the multitude of horrific damages the war inflicted. "Always look a man straight in the face," one resolute nun told her nurses. "Remember he's watching your face to see how you're going to react."

Wood established his mask-making unit in March 1916, and by June 1917, his work had warranted an article in The Lancet, the British medical journal. "I endeavour by means of the skill I happen to possess as a sculptor to make a man's face as near as possible to what it looked like before he was wounded," Wood wrote. "My cases are generally extreme cases that plastic surgery has, perforce, had to abandon; but, as in plastic surgery, the psychological effect is the same. The patient acquires his old self-respect, self assurance, self-reliance,...takes once more to a pride in his personal appearance. His presence is no longer a source of melancholy to himself nor of sadness to his relatives and friends."

Toward the end of 1917, Wood's work was brought to the attention of a Boston-based American sculptor, inevitably described in articles about her as a "socialite." Born in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, Anna Coleman Watts had been educated in Paris and Rome, where she began her sculptural studies. In 1905, at the age of 26, she had married Maynard Ladd, a physician in Boston, and it was here that she continued her work. Her sculptural subjects were mostly decorative fountains—nymphs abounding, sprites dancing—as well as portrait busts that, by today's tastes, appear characterless and bland: vaguely generic portraits of vaguely generic faces. The possibility of furthering the work by making masks for wounded soldiers in France might not have been broached to Ladd but for the fact that her husband had been appointed to direct the Children's Bureau of the American Red Cross in Toul and serve as its medical adviser in the dangerous French advance zones.

In late 1917, after consultation with Wood, now promoted to captain, Ladd opened the Studio for Portrait Masks in Paris, administered by the American Red Cross. "Mrs. Ladd is a little hard to handle as is so often the case with people of great talent," one colleague tactfully cautioned, but she seems to have run the studio with efficiency and verve. Situated in the city's Latin Quarter, it was described by an American visitor as "a large bright studio" on upper floors, reached by way of an "attractive courtyard overgrown with ivy and peopled with statues." Ladd and her four assistants had made a determined effort to create a cheery, welcoming space for her patients; the rooms were filled with flowers, the walls hung with "posters, French and American flags" and rows of plaster casts of masks in progress.

The journey that led a soldier from the field or trench to Wood's department, or Ladd's studio, was lengthy, disjointed and full of dread. For some, it began with a crash: "It sounded to me like some one had dropped a glass bottle into a porcelain bathtub," an American soldier recalled of the day in June 1918 on which a German bullet smashed into his skull in the Bois de Belleau. "A barrel of whitewash tipped over and it seemed that everything in the world turned white."

Stage by stage, from the mud of the trenches or field to first-aid station; to overstrained field hospital; to evacuation, whether to Paris, or, by way of a lurching passage across the Channel, to England, the wounded men were carried, jolted, shuffled and left unattended in long drafty corridors before coming to rest under the care of surgeons. Multiple operations inevitably followed. "He lay with his profile to me," wrote Enid Bagnold, a volunteer nurse (and later the author of National Velvet), of a badly wounded patient. "Only he has no profile, as we know a man's. Like an ape, he has only his bumpy forehead and his protruding lips—the nose, the left eye, gone."

Those patients who could be successfully treated were, after lengthy convalescence, sent on their way; the less fortunate remained in hospitals and convalescent units nursing the broken faces with which they were unprepared to confront the world—or with which the world was unprepared to confront them. In Sidcup, England, the town that was home to Gillies' special facial hospital, some park benches were painted blue; a code that warned townspeople that any man sitting on one would be distressful to view. A more upsetting encounter, however, was often between the disfigured man and his own image. Mirrors were banned in most wards, and men who somehow managed an illicit peek had been known to collapse in shock. "The psychological effect on a man who must go through life, an object of horror to himself as well as to others, is beyond description," wrote Dr. Albee. "...It is a fairly common experience for the maladjusted person to feel like a stranger to his world. It must be unmitigated hell to feel like a stranger to yourself."

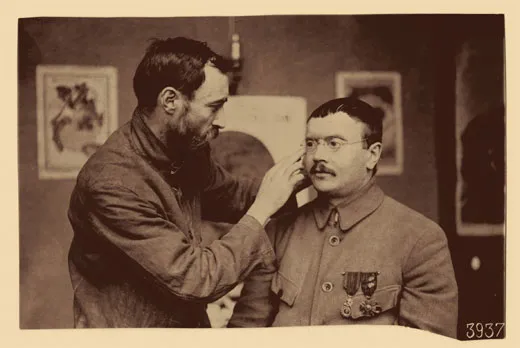

The pains taken by both Wood and Ladd to produce masks that bore the closest possible resemblance to the prewar soldier's uninjured face were enormous. In Ladd's studio, which was credited with better artistic results, a single mask required a month of close attention. Once the patient was wholly healed from both the original injury and the restorative operations, plaster casts were taken of his face, in itself a suffocating ordeal, from which clay or plasticine squeezes were made. "The squeeze, as it stands, is a literal portrait of the patient, with his eyeless socket, his cheek partly gone, the bridge of the nose missing, and also with his good eye and a portion of his good cheek," wrote Ward Muir, a British journalist who had worked as an orderly with Wood. "The shut eye must be opened, so that the other eye, the eye-to-be, can be matched to it. With dexterous strokes the sculptor opens the eye. The squeeze, hitherto representing a face asleep, seems to awaken. The eye looks forth at the world with intelligence."

This plasticine likeness was the basis of all subsequent portraits. The mask itself would be fashioned of galvanized copper one thirty-second of an inch thick—or as a lady visitor to Ladd's studio remarked, "the thinness of a visiting card." Depending upon whether it covered the entire face, or as was often the case, only the upper or lower half, the mask weighed between four and nine ounces and was generally held on by spectacles. The greatest artistic challenge lay in painting the metallic surface the color of skin. After experiments with oil paint, which chipped, Ladd began using a hard enamel that was washable and had a dull, flesh-like finish. She painted the mask while the man himself was wearing it, so as to match as closely as possible his own coloring. "Skin hues, which look bright on a dull day, show pallid and gray in bright sunshine, and somehow an average has to be struck," wrote Grace Harper, the Chief of the Bureau for the Reeducation of Mutilés, as the disfigured French soldiers were called. The artist has to pitch her tone for both bright and cloudy weather, and has to imitate the bluish tinge of shaven cheeks." Details such as eyebrows, eyelashes and mustaches were made from real hair, or, in Wood's studio, from slivered tinfoil, in the manner of ancient Greek statues.

Today, the only images of these men in their masks come from black-and-white photographs which, with their forgiving lack of color and movement, make it impossible to judge the masks's true effect. Static, set for all time in a single expression modeled on what was often a single prewar photograph, the masks were at once lifelike and lifeless: Gillies reports how the children of one mask-wearing veteran fled in terror at the sight of their father's expressionless face. Nor were the masks able to restore lost functions of the face, such as the ability to chew or swallow. The voices of the disfigured men who wore the masks are for the most part known only from meager correspondence with Ladd, but as she herself recorded, "The letters of gratitude from the soldiers and their families hurt, they are so grateful." "Thanks to you, I will have a home," one soldier had written her. "...The woman I love no longer finds me repulsive, as she had a right to do."

By the end of 1919, Ladd's studio had produced 185 masks; the number produced by Wood is not known, but was presumably greater, given that his department was open longer and his masks were produced more quickly. These admirable figures pale only when held against the war's estimated 20,000 facial casualties.

By 1920, the Paris studio had begun to falter; Wood's department had been disbanded in 1919. Almost no record of the men who wore the masks survives, but even within Ladd's one-year tenure it was clear that a mask had a life of only a few years. "He had worn his mask constantly and was still wearing it in spite of the fact that it was very battered and looked awful," Ladd had written of one of her studio's early patients.

In France, the Union des Blessés de la Face (the Union of the Facially Wounded) acquired residences to accommodate disfigured men and their families, and in later years absorbed the casualties of subsequent wars. The fate of similarly wounded Russians and Germans is more obscure, although in postwar Germany, artists used paintings and photographs of the facially mutilated with devastating effect in antiwar statements. America saw dramatically fewer casualties: Ladd reckoned that there were "between two and three hundred men in the American army who require masks"—a tenth the number required in France. In England, sentimental schemes were discussed for the appropriation of picturesque villages, where "maimed and shattered" officers, if not enlisted men, could live in rose-covered cottages, amid orchards and fields, earning their living selling fruit and weaving textiles by way of rehabilitation; but even these inadequate plans came to naught, and the men simply trickled away, out of sight. Few, if any, masks survive. "Surely they were buried with their owners," suggested Wood's biographer, Sarah Crellin.

The treatment of catastrophic casualties during World War I led to enormous advances in most branches of medicine—advances that would be used to advantage, mere decades later, treating the catastrophic casualties of World War II. Today, despite the steady and spectacular advance of medical techniques, even sophisticated modern reconstructive surgery can still not adequately treat the kinds of injuries that condemned men of the Great War to live behind their masks

Anna Coleman Ladd left Paris after the armistice, in early 1919, and was evidently sorely missed: "Your great work for the French mutilés is in the hands of a little person who has the soul of a flea," a colleague wrote to her from Paris. Back in America, Ladd was extensively interviewed about her war work, and in 1932, she was made a Chevalier of the French Legion of Honor. She continued to sculpt, producing bronzes that differed remarkably little in style from her prewar pieces; her war memorials inevitably depict granite-jawed warriors with perfect—one is tempted to say mask-like—features. She died at age 60 in Santa Barbara in 1939.

Francis Derwent Wood died in London in 1926 at age 55. His postwar work included a number of public monuments, including war memorials, the most poignant of which, perhaps, is one dedicated to the Machine Gun Corps in Hyde Park Corner, London. On a raised plinth, it depicts the young David, naked, vulnerable, but victorious, who signifies that indispensable figure of the war to end all wars—the machine-gunner. The monument's inscription is double-edged, alluding to both the heroism of the individual gunner and the preternatural capability of his weapon: "Saul hath slain his thousands, but David his tens of thousands."

Caroline Alexander is the author of The Bounty: The True Story of the Mutiny on the Bounty.