Resurrecting Pompeii

A new exhibition brings the doomed residents of Pompeii and Herculaneum vividly to life

Daybreak, August 25, A.D. 79. Under a lurid and sulfurous sky, a family of four struggles down an alley filled with pumice stones, desperately trying to escape the beleaguered city of Pompeii. Leading the way is a middle-aged man carrying gold jewelry, a sack of coins and the keys to his house. Racing to keep up are his two small daughters, the younger one with her hair in a braid. Close behind is their mother, scrambling frantically through the rubble with her skirts hiked up. She clutches an amber statuette of a curly-haired boy, perhaps Cupid, and the family silver, including a medallion of Fortune, goddess of luck.

But neither amulets nor deities can protect them. Like thousands of others this morning, the four are overtaken and killed by an incandescent cloud of scorching gases and ash from Mount Vesuvius. In the instant before he dies, the man strains to lift himself from the ground with one elbow. With his free hand, he pulls a corner of his cloak over his face, as though the thin cloth will save him.

The hellish demise of this vibrant Roman city is detailed in a new exhibition, “Pompeii: Stories from an Eruption,” at Chicago’s Field Museum through March 26. Organized by the office of Pompeii’s archaeological superintendent, the exhibition includes nearly 500 objects (sculpture, jewelry, frescoes, household objects and plaster casts of the dead), many of which have never been seen outside Italy.

The destruction of Pompeii and the nearby coastal town of Herculaneum is undoubtedly history’s most storied natural disaster. The ancient Roman cities were buried under layers of volcanic rock and ash—frozen in time—until their rediscovery and exploration in the 18th century. Early excavators didn’t much care where a particular statue or mosaic fragment had been found and what stories might be coaxed from them. By contrast, “Pompeii: Stories from an Eruption” employs archaeological techniques to link artifacts to the lives of the people who once lived with them.

To most people today, the scope of the calamity in a.d. 79—natural forces transforming bustling areas overnight into cities of the dead—has long seemed unimaginable (if less so in the wake of Hurricane Katrina and Southeast Asia’s 2004 tsunami). Moreover, the passage of time has softened the horror of Vesuvius’ human toll. “Many disasters have befallen the world, but few have brought posterity so much joy,” wrote the German poet Goethe after touring Pompeii’s ruins in the 1780s, some 40 years after its rediscovery. Indeed, Pompeii’s very destruction is what has kept it so remarkably alive. “If an ancient city survives to become a modern city, like Naples, its readability in archaeological terms is enormously reduced,” says Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, director of the British School at Rome. “It’s a paradox of archaeology: you read the past best in its moments of trauma.”

In the Field Museum exhibition, some of those moments are brought eerily to life by plaster casts of Pompeii and Herculaneum’s residents at the moment the eruption overtook them. The doomed couple fleeing down an alley with their two daughters (if they were indeed a family; some have suggested the man was a slave) were the first Vesuvius victims to be so revealed, although these early casts are not in the exhibition. In 1863, an ingenious Italian archaeologist named Giuseppe Fiorelli noticed four cavities in the hardened layer of once-powdery ash that covered Pompeii to a depth of ten feet. By filling the holes with plaster, he created disturbingly lifelike casts of this long-departed Pompeiian family in its final horrifying moments. It was as though an eyewitness from antiquity had stepped forward with photographs of the disaster.

Pompeii in A.D. 79 was a thriving provincial center with a population of between 10,000 and 20,000 people a few miles from the Bay of Naples. Its narrow streets, made narrower by street vendors and shops with jutting cloth awnings, teemed with tavern goers, slaves, vacationers from the north and more than a few prostitutes. A colossal new aqueduct supplied running water from the Lower Apennine mountains, which gushed from fountains throughout the city, even in private homes. But the key to Pompeii’s prosperity, and that of smaller settlements nearby like Oplontis and Terzigna, was the region’s rich black earth.

“One of the ironies of volcanoes is that they tend to produce very fertile soils, and that tends to lure people to live around them,” says Field Museum geologist Philip Janney. Olive groves supported many a wealthy farmer in Pompeii’s suburbs, as suggested by an exquisite silver goblet decorated with olives in high relief. Pompeiian wine was shipped throughout Italy. (The Roman statesman and writer Pliny the Elder complained it produced a nasty hangover.)

At the House of the Centenary, a lavish residence converted to a winery in the first century A.D., an impish bronze satyr, once part of a fountain, squeezes wine from a wineskin. Found on a wall in the same house, a large, loosely painted fresco depicts the wine god Bacchus festooned in grapes before what some scholars have identified as an innocent-looking Mount Vesuvius, its steep slopes covered with vineyards.

In the towns below it, most people would not have known that Vesuvius was a volcano or that a Bronze Age settlement in the area had been annihilated almost 2,000 years before. And that was not the first time. “Vesuvius is actually inside the exploded skeleton of an older volcano,” says Janney. “If you look at an aerial photograph, you can see the remaining ridge of a much larger volcano on the north side.” It likely blew, violently, long before human settlement.

Southern Italy is unstable ground, Janney says. “The African plate, on which most of the Mediterranean Sea rests, is actually diving beneath the European plate.” That kind of underground collision produces molten rock, or magma, rich in volatile gases such as sulfur dioxide. Under pressure underground, the gases stay dissolved. But when the magma rises to the surface, the gases are released. “When those kinds of volcanoes erupt,” he says, “they tend to erupt explosively.” To this day, in fact, Vesuvius remains one of the world’s most dangerous volcanoes; some 3.5 million Italians live in its shadow, and about 2 million tourists visit the ruins each year. Although monitoring devices are in place to warn of the volcano’s restiveness, “if there is a major eruption with little warning and the winds are blowing toward Naples,” says Janney, “you could have tremendous loss of life.”

Had Roman knowledge in the summer of 79 been less mythological and more geological, Pompeiians might have recognized the danger signs. A major earthquake 17 years earlier had destroyed large swaths of the city; much of it was still being rebuilt. Early in August, a small earthquake had rocked the town. Wells had mysteriously gone dry. Finally, at about one in the afternoon on August 24, the mountain exploded.

Fifteen miles away, Pliny the Elder witnessed the eruption from a coastal promontory. (He would die during a rescue mission the next morning, perhaps choked by ash after landing on the beach near Pompeii.) Watching with him was his 17-year-old nephew, known as Pliny the Younger, who has given history its only eyewitness account. Above one of the mountains across the bay, he noticed “a cloud of unusual size and appearance.” It reminded him of an umbrella pine tree “for it rose to a great height on a sort of trunk and then split off into branches.” The cloud was actually a scorching column of gas mixed with thousands of tons of rock and ash that had just blasted out of the earth at supersonic speed.

The column’s great heat continued to push it skyward until it reached a height of nearly 20 miles, says Janney. “As the column cooled, it began to spread out horizontally and drift with the wind, which is why [the younger] Pliny compared it to a pine tree. As it cooled further, solid particles started to rain down. That’s what began to fall on Pompeii.”

At first, the choking rain of ash and small pumice stones wasn’t lethal. An estimated 80 percent of Pompeii’s residents likely fled to the safety of neighboring villages, but more than 2,000 stayed behind, huddled inside buildings. By nightfall, the shower of debris had grown denser—and deadlier. Smoldering rocks bombarded the city. Roofs began to collapse. Panicked holdouts now emerged from their hiding places in cellars and upper floors and clogged Pompeii’s narrow, rubble-filled streets.

Perhaps the most poignant object in the exhibition is the plaster cast of a young child stretched out on his back with his toes pointed and his eyes closed. He might be sleeping, except his arms are lifted slightly. He was found with his parents and a younger sibling in the House of the Golden Bracelet, once a luxurious three-story home decorated with brightly colored frescoes. The family had sought refuge under a staircase, which then collapsed and killed them. The powdery ash that soon buried them was so finely textured that the cast reveals even the child’s eyelids. Coins and jewelry lay on the floor of the house. Among the finery was a thick gold bracelet weighing 1.3 pounds (the source of the building’s name) in the popular shape of a two-headed snake curled so that each mouth gripped one side of a portrait medallion. Pompeii’s serpents were unsullied by biblical associations; in ancient Italy, snakes meant good luck.

Pompeii’s patron deity was Venus, the Roman goddess of love and beauty. Small wonder that the city’s ruins were filled with erotic art, perfume bottles and extravagant gold jewelry, including earrings set with pearls, gold balls and uncut emeralds bunched like grapes. “I see they do not stop at attaching a single large pearl in each ear,” the Roman philosopher Seneca observed during the first century A.D. “Female folly had not crushed men enough unless two or three entire patrimonies hung from their ears.” The showiest pieces of jewelry in the exhibition are the catenae: gold chains up to six feet long that wrapped tightly around a woman’s waist, then crossed her chest and shoulders bandoleer-style.

Like the family of four found in the alley with a Cupid statuette and a good-luck charm, Pompeii’s victims often died carrying the objects they valued most. A woman fleeing through one of the city gates clutched a gold-and-silver statuette of fleet-footed Mercury, the god of safe passage. Across town at the city’s colonnaded outdoor gymnasium, where close to 100 people perished, one victim was found holding a small wooden box against his chest. Inside were scalpels, tweezers and other surgical tools. A doctor, he may have grabbed his medical kit to help the injured, expecting the worst would soon be over.

In a small room at an inn on the southern outskirts of Pompeii, a woman of about 30 died wearing two heavy gold armbands, a ring and a gold chain. In a handbag were more bracelets and rings, another gold chain, a necklace and a long catena of thick, braided gold. Roman jewelry was rarely inscribed, but inside one of her armbands, shaped like a coiled snake, are the words: DOM(I)NUS ANCILLAE SUAE, “From the master to his slave-girl.”

“Since its excavation in the 18th century, Pompeii has acquired the reputation of being a permissive, sybaritic place,” says University of Maryland classics professor Judith Hallett. “Throughout the ancient Greco-Roman world, slaves had to cater to the whims of the elite. I think all slaves, male and female, were on duty as potential sex partners for their male masters. If you were a slave, you could not say no.”

Evidence of Pompeii’s class system abounds. While many victims of the eruption died carrying hoards of coins and jewelry, many more died empty-handed. During the night of the 24th, the worsening rain of ash and stones blocked doors and windows on the ground floor and poured in through atrium skylights at the House of the Menander, one of the city’s grandest homes. In the darkness, a group of ten people with a single lantern, likely slaves, frantically tried to climb from the pumice-filled entrance hall to the second floor. In a nearby hall facing a courtyard, three more struggled to dig an escape route with a pickax and a hoe. All died. Aside from their tools, they left behind only a coin or two, some bronze jewelry and a few glass beads.

In contrast, the master of the house, Quintus Poppeus, a wealthy in-law of Emperor Nero who wasn’t home at the time, left behind plenty of loot. Hidden in an underground passage, archaeologists discovered two wooden treasure chests. In them were jewels, more than 50 pounds of carefully wrapped silverware, and gold and silver coins. His artwork, at least, Quintus left in plain sight. Under a colonnade was a marble statue of Apollo stroking a griffin as it playfully jumped up against his leg. The statue is in such superb condition that it might have been carved last week.

By encasing objects almost as tightly as an insect trapped in amber, the fine-grained volcanic ash that smothered Pompeii proved a remarkable preservative. Where the public market used to be, archaeologists have dug up glass jars with fruit still in them. An oven in an excavated bakery was found to contain 81 carbonized loaves of bread. A surprising amount of graffiti was also preserved. Blank, mostly windowless Pompeiian houses, for instance, presented seemingly irresistible canvases for passersby to share their thoughts. Some of the messages sound familiar, only the names have changed: Auge Amat Allotenum (Auge Loves Allotenus) C Pumidius Dipilus Heic Fuit (Gaius Pumidius Dipilus Was Here). A half-dozen walls around town offer comments on the relative merits of blondes and brunettes.

Several inscriptions salute local gladiators. The city’s 22,000-seat amphitheater was one of the first built specifically for blood sport. Gladiators came mostly from the region’s underclass—many were slaves, criminals or political prisoners—but charismatic victors could rise to celebrity status. Celadus the Thracian was “the ladies’ choice,” according to one inscription.

The exhibition includes a magnificent bronze helmet decorated with scenes of vanquished barbarians in high relief above the armored visor. (When losers were put to death, their bodies were carted off to a special room where they were relieved of their armor.) More than a dozen other such helmets have been unearthed in the gladiators’ barracks, along with assorted weaponry. Also discovered there were the remains of a woman wearing lots of expensive jewelry, inspiring speculation that she was a wealthy matron secretly visiting her gladiator lover at the time of Vesuvius’ eruption. More likely, considering the 18 other skeletons found in the same small room, she was simply seeking refuge from the deadly ash.

Nine miles northwest of Pompeii, the seaside resort of Herculaneum experienced Vesuvius’ fury in a different way. Here the enemy, when it came, was what geologists call a pyroclastic surge: superheated (1,000-degree Fahrenheit) ash and gas traveling with the force of a hurricane.

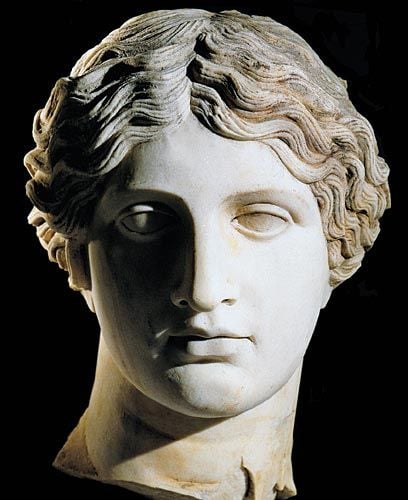

Herculaneum was smaller and wealthier than Pompeii. Roman senators built terraced homes here overlooking the Bay of Naples. The grounds of the sumptuous Villa of the Papyri, where Julius Caesar’s father-in-law may once have lived, included a swimming pool more than 200 feet long. Inside the villa, named for its immense library of scrolls, were frescoes, mosaics and more than 90 statues. Exhibition highlights from the trove include two recently unearthed marble statues: a regal standing Hera, queen of the gods, and a finely chiseled head of an Amazon warrior in the style of Greece’s Classical period, both on display for the first time.

Shortly after noon on August 24, the sky over Herculaneum darkened ominously. The wind, however, pushed Vesuvius’ ash well to the southeast. The vast majority of Herculaneum’s roughly 5,000 inhabitants probably fled that same afternoon and evening; the remains of only a few dozen people have been found in the city itself. Not long after midnight, a glowing cloud of superheated gases, ash and debris roared down the mountain’s western flank toward the sea. “Pyroclastic surges move quite rapidly, between 50 and 100 miles per hour,” says geologist Janney. “You can’t outrun them. You don’t even get much warning.” In Pompeii, the first to die had been crushed or buried alive. In Herculaneum, most of the victims were incinerated.

The younger Pliny witnessed the surge’s arrival from across the bay. Even at the comparatively safe distance of 15 miles, it triggered panic and confusion. “A fearful black cloud was rent by forked and quivering bursts of flame, and parted to reveal great tongues of fire,” he wrote. “You could hear the shrieks of women, the wailing of infants, and the shouting of men....Many besought the aid of the gods, but still more imagined there were no gods left and that the universe was plunged into eternal darkness.”

Large numbers of Herculaneum’s residents fled toward the sea in hopes of escaping by boat. Along the seafront archaeologists in the 1980s discovered the remains of nearly 300 victims. Carrying satchels filled with cash, jewels and amulets, they crowded into boathouses on the beach. The sudden torrent of searing gas and ash must have caught them by surprise. The surge was so hot that a cache of bronze and silver coins in a wicker basket were fused into a solid block of metal. By the time it was over (there were 12 surges in all), the entire city was buried under 75 feet of rock and ash.

In Pompeii, the falling ash had let up by about 6 p.m. on the 24th. But as survivors ventured out into the streets on the morning of the 25th, a pyroclastic surge swept in, killing everyone in its path. Two more surges followed, but these covered over a silent, lifeless city.

After its rediscovery in the 18th century, Pompeii grew to a stature it never enjoyed in ancient times, as well-bred tourists, some with shovels in hand, took wistful strolls through its emerging ruins. “From the 1760s onward, the grand tour through Italy was considered by the aristocracy of Europe to be a necessary part of growing up,” says archaeologist Andrew Wallace-Hadrill.

The more serious-minded visitors drew inspiration from the astonishing artwork coming to light. Published drawings of Pompeii’s richly colored interiors helped trigger the neo-Classical revival in European art and architecture. Well-appointed British homes in the early 19th century often had an Etruscan Room, whose décor was actually Pompeiian.

The story of the pagan city annihilated overnight by fire and brimstone was also an irresistible subject for 19th-century paintings and novels, notably Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s 1834 potboiler, The Last Days of Pompeii. “Novels like that and Quo Vadis drew on the material evidence from Pompeii to play up the idea of Roman decadence,” says classicist Judith Hallett. “It was presented as exactly what Christianity promised to rescue mankind from.”

In the months after Vesuvius’ eruption, “a lot of Pompeiians came back to dig through the ash and see what they could recover,” says anthropologist Glenn Storey of the University of Iowa, a consultant to the exhibition. “The Emperor Titus declared Pompeii an emergency zone and offered financial assistance for cleanup and recovery.” But the buried towns were beyond salvaging. “When this wasteland regains its green,” wrote the Roman poet Statius not long after the eruption, “will men believe that cities and peoples lie beneath?” Eventually, the towns were dropped from local maps. Within a few centuries, settlers had repopulated the empty terrain, unconcerned with what lay below. They planted grapevines and olive trees in the fertile black soil.