Star-Spangled Banner Back on Display

After a decade’s conservation, the flag that inspired the National Anthem returns to its place of honor on the National Mall

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/starspangledbanner_nov08_631.jpg)

Long before it flew to the moon, waved over the White House or was folded into tight triangles at Arlington National Cemetery; before it sparked fiery Congressional debates, reached the North Pole or the summit of Mount Everest; before it became a lapel fixture, testified to the Marines' possession of Iwo Jima, or fluttered over front porches, firetrucks and construction cranes; before it inspired a national anthem or recruiting posters for two world wars, the American ensign was just a flag.

"There was nothing special about it," says Scott S. Sheads, historian at Baltimore's Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine, speaking of a time when a new nation was struggling for survival and groping toward a collective identity. That all changed in 1813, when one enormous flag, pieced together on the floor of a Baltimore brewery, was first hoisted over the federal garrison at Fort McHenry. In time the banner would take on larger meaning, set on a path to glory by a young lawyer named Francis Scott Key, passing into one family's private possession and emerging as a public treasure.

Succeeding generations loved and honored the Stars and Stripes, but this flag in particular provided a unique connection to the national narrative. Once it was moved to the Smithsonian Institution in 1907, it remained on almost continuous display. After almost 200 years of service, the flag had slowly deteriorated almost to the point of no return. Removed from exhibit in 1998 for a conservation project that cost about $7 million, the Star-Spangled Banner, as it had become known, returns to center stage this month with the reopening of the renovated National Museum of American History on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

Its long journey from obscurity began on a blazing July day in 1813, when Mary Pickersgill, a hardworking widow known as one of the best flag makers in Baltimore, received a rush order from Maj. George Armistead. Newly installed as commander of Fort McHenry, the 33-year-old officer wanted an enormous banner, 30 by 42 feet, to be flown over the federal garrison guarding the entrance to Baltimore's waterfront.

There was some urgency to Armistead's request. The United States had declared war in June 1812 to settle its disputed northern and western borders and stop the British from impressing American seamen; the British, annoyed by American privateering against their merchant ships, readily took up the challenge. As the summer of 1813 unfolded, the enemies were trading blows across the Canadian border. Then British war vessels appeared in the Chesapeake Bay, menacing shipping, destroying local batteries and burning buildings up and down the estuary. As Baltimore prepared for war, Armistead ordered his big new flag—one the British would be able to see from miles away. It would signal that the fort was occupied and prepared to defend the harbor.

Pickersgill got right to work. With her daughter Caroline and others, she wrestled more than 300 yards of English worsted wool bunting to the floor of Claggett's brewery, the only space in her East Baltimore neighborhood large enough to accommodate the project, and started measuring, snipping and fitting.

To make the flag's stripes, she overlapped and stitched eight strips of red wool and alternated them with seven strips of undyed white wool. While the bunting was manufactured in 18-inch widths, the stripes in her design were each two feet wide, so she had to splice in an extra six inches all the way across. She did it so smoothly that the completed product would look like a finished whole—and not like the massive patchwork it was. A rectangle of deep blue, about 16 by 21 feet, formed the flag's canton, or upper left quarter. Sitting on the brewery floor, she stitched a scattering of five-pointed stars into the canton. Each one, fashioned from white cotton, was almost two feet across. Then she turned the flag over and snipped out blue material from the backs of the stars, tightly binding the edges; this made the stars visible from either side.

"My mother worked many nights until 12 o'clock to complete it in the given time," Caroline Pickersgill Purdy recalled years later. By mid-August, the work was done—a supersize version of the Stars and Stripes. Unlike the 13-star ensign first authorized by Congress on June 14, 1777, this one had 15 stars to go with the 15 stripes, acknowledging the Union's latest additions, Vermont and Kentucky.

Mary Pickersgill delivered the finished flag on August 19, 1813, along with a junior version. The smaller flag, 17 by 25 feet, was to be flown in inclement weather, saving wear and tear on the more expensive one, not to mention the men who hoisted the unwieldy monster up the flagpole.

The government paid $405.90 for the big flag, $168.54 for the storm version (roughly $5,500 and $2,300, respectively, in today's currency). For a widow who had to make her own way, Pickersgill lived well, eventually buying a brick house on East Pratt Street, supporting her mother and daughter there and furnishing the place with luxuries such as floor coverings of painted sailcloth.

"Baltimore was a very good place to have a flag business," says Jean Ehmann, a guide who shows visitors around the Pickersgill house, now a National Historic Landmark known as the Star-Spangled Banner Flag House. "Ships were coming and going from around the world. All of them needed flags—company flags, signal flags, country flags."

There is no record of when Armistead's men first raised their new colors over Fort McHenry, but they likely did so as soon as Pickersgill delivered them: a sizable British flotilla had just appeared on Baltimore's doorstep, sailing into the mouth of the Patapsco River on August 8. The city braced itself, but after the enemies eyed each other for several days, the British weighed anchor and melted into the haze. They had surveyed the region's sketchy defenses and concluded that Washington, Baltimore and environs would be ripe for attack when springtime opened a new season of war in 1814.

That season looked like a disaster in the making for the Americans. When summer arrived in Canada, so did 14,000 British combatants ready to invade the United States across Lake Champlain. On the Chesapeake, 50 British warships under Vice Adm. Sir Alexander Cochrane headed for Washington, where, in August 1814, the invaders burned the presidential mansion, the Capitol and other public buildings. The British then headed for Baltimore, in part to punish the city's privateers, who had captured or burned 500 British ships since hostilities erupted two years before.

After maneuvering their ships into position and testing the range of their guns, the British opened the main assault on Baltimore on September 13. Five bomb ships led the way, lobbing 190-pound shells into Fort McHenry and unleashing rockets with exploding warheads. The fort answered—but with little effect. "We immediately opened Our Batteries and Kept up a brisk fire from Our Guns and Mortars," Major Armistead reported, "but unfortunately our Shot and Shells all fell considerably Short." The British kept up a thunderous barrage throughout the 13th and into the predawn hours of the 14th.

During the 25-hour battle, says historian Sheads, the British unleashed about 133 tons of shells, raining bombs and rockets on the fort at the rate of one projectile per minute. The thunder they produced shook Baltimore to its foundations and was heard as far away as Philadelphia. Hugging walls and taking the hits wore on the defenders. "We were like pigeons tied by the legs to be shot at," recalled Judge Joseph H. Nicholson, an artillery commander within the fort. Capt. Frederick Evans looked up to see a shell the size of a flour barrel screaming toward him. It failed to explode. Evans noticed handwritten on its side: "A present from the King of England."

Despite the din and the occasional hits, the Americans sustained few casualties—four out of a thousand were killed, 24 wounded—as the fort's aggressive gunnery kept the British at arm's length.

After a furious thunderstorm broke over Baltimore about 2 p.m. on September 13, the storm flag was likely hoisted in place of its larger sibling, although official descriptions of the battle mention neither. After all, says Sheads, it was "just an ordinary garrison flag."

High winds and rain lashed the city throughout the night, as did the man-made storm of iron and sulfur. Fort McHenry's fate remained undecided until the skies cleared on September 14 and a low-slanting sun revealed that the battered garrison still stood, guns at the ready. Admiral Cochrane called a halt to the barrage about 7 a.m., and silence fell over the Patapsco River. By 9 a.m. the British were filling their sails, swinging into the current and heading downriver. "As the last vessel spread her canvas," wrote Midshipman Richard J. Barrett of HMS Hebrus, "the Americans hoisted a most superb and splendid ensign on their battery, and fired at the same time a gun of defiance."

Major Armistead was absent from celebrations inside the fort that day. Brought low by what he later described as "great fatigue and exposure," he remained in bed for almost two weeks, unable to command the fort or to write his official account of the battle. When he finally filed a 1,000-word report on September 24, he made no mention of the flag—now the one thing most people associate with Fort McHenry's ordeal.

The reason they do, of course, is Francis Scott Key. The young lawyer and poet had watched the bombardment from the President, an American truce ship the British had held throughout the battle after he negotiated the release of an American hostage. On the morning of September 14, Key had also seen what Midshipman Barrett described—the American colors unfurling over the fort, the British ships stealing away—and Key knew what it meant: threatened by the most powerful empire on earth, the city had survived the onslaught. The young nation might even survive the war.

Rather than return to his home outside Washington, D.C., Key checked into a Baltimore hotel that evening and finished a long poem about the battle, with its "rockets' red glare" and "bombs bursting in air." He conveyed the elation he felt at seeing what was probably Mrs. Pickersgill's big flag flying that morning. Fortunately for posterity, he did not call it Mrs. Pickersgill's flag, but referred to a "star-spangled banner." Key wrote quickly that night—in part because he already had a tune in his head, a popular English drinking song called "To Anacreon in Heaven," which fit the meter of his lines perfectly; in part because he lifted a few phrases from a poem he had composed in 1805.

The next morning, Key shared his new work with his wife's brother-in-law Joseph Nicholson, the artillery commander who had been inside Fort McHenry throughout the battle. Although it is almost certain that the flag Key glimpsed at the twilight's last gleaming was not the one he saw by the dawn's early light, Nicholson did not quibble—Key was, after all, a poet, not a reporter. Nicholson was enthusiastic. Less than a week later, on September 20, 1814, the Baltimore Patriot & Evening Advertiser published Key's poem, then titled "Defence of Fort M'Henry." It would be reprinted in at least 17 papers around the country that fall. That November, Thomas Carr of Baltimore united lyrics and song in sheet music, under the title "The Star-Spangled Banner: A Patriotic Song."

Key's timing could not have been better. Washington was in ruins, but the war's tide was turning. On September 11, as Baltimore prepared to meet Admiral Cochrane's assault, Americans trounced a British squadron on Lake Champlain, blocking its invasion from Canada. With Britain's defeat in New Orleans the following January, the War of 1812 was effectively over.

Having won independence a second time, the nation breathed a collective sigh of relief. As gratitude mixed with an outpouring of patriotism, Key's song and the flag it celebrated became symbols of the victory. "For the first time, someone put into words what the flag meant to the country," says Sheads. "That is the birth of what we recognize today as a national icon."

Major Armistead, showered with honors for his performance at Fort McHenry, had little time to enjoy his new fame. Although he continued to suffer bouts of fatigue, he remained on active duty. At some point the big flag left the fort and was taken to his home in Baltimore. There is no record that it—officially government property—was ever transferred to him. "That is the big question," says Sheads. "How did he end up with the flag? There is no receipt." Perhaps the banner was so tattered from use that it was no longer considered fit for service—a fate it shared with Armistead. Just four years after his triumph, he died of unknown causes. He was 38.

The big banner passed to his widow, Louisa Hughes Armistead, and became known as her "precious relic" in the local press. She apparently kept it within the Baltimore city limits but lent it out for at least five patriotic celebrations, thereby helping to lift a locally revered artifact into the national consciousness. On the most memorable of those occasions, the flag was displayed at Fort McHenry with George Washington's campaign tent and other patriotic memorabilia when Revolutionary War hero the Marquis de Lafayette visited in October 1824. When Louisa Armistead died in 1861, she left the flag to her daughter, Georgiana Armistead Appleton, just as a new war broke out. That conflict, the bloodiest in America's history, brought new attention to the flag, which became a symbol of the momentous struggle between North and South.

The New York Times, reacting to the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter in April 1861, railed against traitors who fired upon the Stars and Stripes, which "shall yet wave over Richmond and Charleston, and Mobile and New Orleans." Harper's Weekly called the American flag "the symbol of the Government....The rebels know that, as surely as the sun rises, the honor of the country's flag will presently be vindicated."

In Baltimore, a Union city seething with Confederate sympathizers, Major Armistead's grandson and namesake, George Armistead Appleton, was arrested attempting to join the rebellion. He was imprisoned in Fort McHenry. His mother, Georgiana Armistead Appleton, found herself in the ironic position of decrying her son's arrest and pulling for the South, while clinging to the Star-Spangled Banner, by then the North's most potent icon. She had been entrusted to protect it, she said, "and a jealous and perhaps selfish love made me guard my treasure with watchful care." She kept the famous flag locked away, probably at her home in Baltimore, until the Civil War ran its course.

Like other Armisteads, Georgiana Appleton found the flag both a source of pride and a burden. As often happens in families, her inheritance generated hard feelings within the clan. Her brother, Christopher Hughes Armistead, a tobacco merchant, thought the flag should have come to him and exchanged angry words with his sister over it. With evident satisfaction, she recalled that he was "forced to give it up to me and with me it has remained ever since, loved and venerated." As the siblings squabbled, Christopher's wife expressed relief that the flag was not theirs: "More battles have been fought over that flag than were ever fought under it, and I, for one, am glad to be rid of it!" she reportedly said.

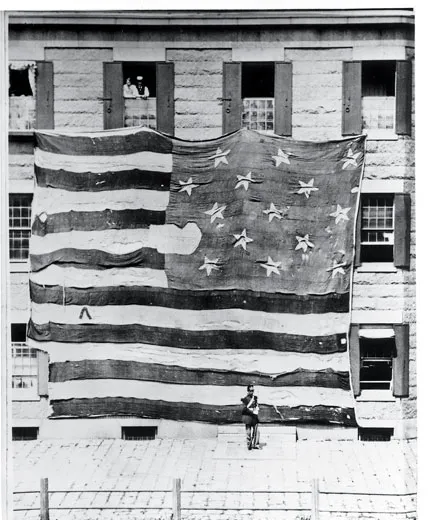

With the end of the Civil War and the approach of the nation's centennial in 1876, Georgiana Appleton was pressed by visitors who wanted to see the flag and by patriots wishing to borrow it for ceremonies. She obliged as many of them as she thought reasonable, even allowing some to snip fragments from the banner as souvenirs. Just how many became obvious in 1873, when the flag was photographed for the first time, hanging from a third-floor window at the Boston Navy Yard.

It was a sad sight. Red stripes had split from their seams, drooping away from white ones; much of the bunting appeared to be threadbare; the banner was riddled with holes, from wear and tear, insect damage—and perhaps combat; a star was gone from the canton. The rectangular flag that Mary Pickersgill had delivered to Fort McHenry was now almost square, having lost about eight feet of material.

"Flags have a hard life," says Suzanne Thomassen-Krauss, chief conservator of the Star-Spangled Banner Project at the National Museum of American History. "The amount of wind damage that happens in a very short time is a major culprit in the deterioration of flags."

Thomassen-Krauss suggests that this banner's fly end, the part that flies free, was probably in tatters when the Armistead family took possession of it. By the time it reached Boston for its 1873 photo op, the ragged end had been trimmed and bound with thread to contain further deterioration. According to Thomassen-Krauss, fly end remnants were likely used to patch more than 30 other parts of the flag. Other trimmings were probably the source for most of the souvenirs the Armisteads handed out.

"Pieces of the flag have occasionally been given to those who [were] deemed to have a right to such a memento," Georgiana Appleton acknowledged in 1873. "Indeed, had we given all that we had been importuned for, little would be left to show." Contrary to widespread belief, the flag's missing star was taken out not by shrapnel or rocket fire, but most likely by scissors. It was "cut out for some official person," Georgiana wrote, though she never named the recipient.

The 1873 photograph reveals another telling detail: the presence of a prominent red chevron stitched into the sixth stripe from the bottom. The voluble Georgiana Appleton never explained it. But historians have suggested it might have been a monogram—in the form of the letter "A" from which the cross-bar has been dropped or was never pieced in, placed there to signify the Armisteads' strong sense of ownership.

That familial pride burned bright in Georgiana Appleton, who fretted over the banner's well-being even as she lent it out, snipped pieces from it and grew old along with a family relic that had come into being only four years before she did. She lamented that it was "just fading away." So was she. When she died at age 60 in 1878, she left the flag to a son, Eben Appleton.

Like family members before him, Eben Appleton—33 at the time he took possession of the flag—felt a keen responsibility to safeguard what, by then, had become a national treasure, much in demand for patriotic celebrations. Aware of its fragile state, he was reluctant to part with it. Indeed, it would appear that he lent it out only once, when the flag made its last public appearance of the 19th century, appropriately enough in Baltimore.

The occasion was the city's sesquicentennial, celebrated October 13, 1880. The parade that day included nine men in top hats and black suits—the last of those who had fought under the banner in 1814. The flag itself, bundled into the lap of a local historian named William W. Carter, rode in a carriage, drawing cheers, a newspaper reported, "as the tattered old relic was seen by the crowds." When the festivities ended, Appleton packed it up and returned to his home in New York City.

There he continued to field requests from civic leaders and patriotic groups, who grew exasperated when he turned them down. When a committee of Baltimoreans publicly questioned whether the Armisteads legally owned the banner, Appleton was infuriated. He locked it in a bank vault, declined to disclose its location, kept his address secret and refused to discuss the flag with anyone, "having been much annoyed about his heirloom all his life," according to a sister.

"People were banging on his door, bothering him all the time to borrow the flag," says Anna Van Lunz, curator at the Fort McHenry historical monument. "He became kind of a recluse."

Eben Appleton shipped the flag to Washington in July 1907, relieved to entrust his family's inheritance—and its attendant responsibility—to the Smithsonian Institution. Initially a loan, Appleton made the transaction permanent in 1912. At that point, his family's flag became the nation's.

The Smithsonian has kept the flag on almost continuous public view even while fretting about its condition. "This sacred relic is but a frail piece of bunting, worn, frayed, pierced and largely in tatters," Assistant Secretary Richard Rathbun said in 1913.

In 1914, the Institution engaged restorer Amelia Fowler to shore up its most prized possession. Commandeering space in the Smithsonian Castle, she set ten needle-women to work removing the heavy canvas backing that had been attached to the flag in 1873 and, with some 1.7 million stitches, painstakingly attaching a new backing of Irish linen. Her work kept the flag from falling apart for nearly a century, as it was displayed in the Arts and Industries Building until 1964, then in the Museum of History and Technology, later renamed the National Museum of American History.

The song the banner inspired had become a regular feature at ballgames and patriotic events by the early 20th century. Around the same time, veterans groups launched a campaign to have Key's composition formally designated as the national anthem. By 1930, five million citizens had signed a petition in support of the idea, and after veterans recruited a pair of sopranos to sing the song before the House Judiciary Committee, Congress adopted "The Star-Spangled Banner" as the national anthem the next year.

When war threatened Washington in 1942, Smithsonian officials quietly whisked the flag and other treasures to a warehouse in Luray, Virginia, to protect them. Returned to the capital in 1944, the flag provided a backdrop for inaugural balls, presidential speeches and countless public events. But constant exposure to light and ambient pollution took their toll, and the flag was removed from exhibit in the National Museum of American History in 1998 for a thorough conservation treatment, aimed at extending the flag's life for another century.

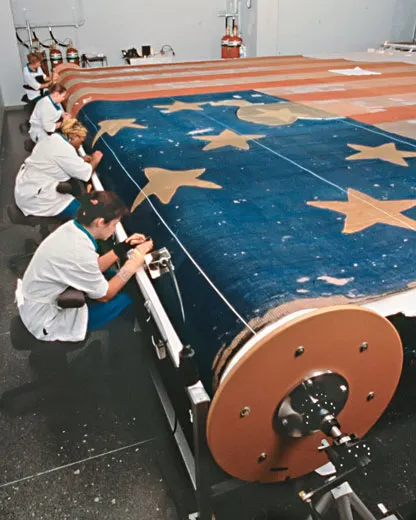

Conservators cleaned it with a solution of water and acetone, removing contaminants and reducing acidity in the fabric. During a delicate operation that took 18 months, they removed Amelia Fowler's linen backing. Then they attached—to the other side of the flag—a new backing made of a sheer polyester fabric called Stabiltex. As a result, visitors will see a side of the flag that had been hidden from view since 1873.

These high-tech attentions have stabilized the flag and prepared it for a new display room at the heart of the renovated museum. There the flag that began life on a brewery floor is sealed in a pressurized chamber. Monitored by sensors, shielded by glass, guarded by a waterless fire-suppression system and soothed by temperature and humidity controls, it lies on a custom-built table that allows conservators to care for it without having to move it. "We really want this to be the last time it's handled," says Thomassen-Krauss. "It's getting too fragile for moving and handling."

So the old flag survives, bathed in dim light, floating out of the darkness, just as it did on that uncertain morning at Fort McHenry.

Robert M. Poole is the magazine's contributing editor. He last wrote about Winslow Homer's watercolors, in the May Issue.