8 Famous People Who Missed the Lusitania

For one reason or another, these lucky souls never boarded the doomed ship whose sinking launched America’s involvement in WWI

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Lusitania-end-of-voyage-631.jpg)

When the First World War began, in the summer of 1914, the Lusitania was among the most glamorous and celebrated ships in the world—at one time both the largest and fastest afloat. But the British passenger liner would earn a far more tragic place in history on May 7, 1915, when it was torpedoed by a German submarine off the coast of Ireland, with the loss of nearly 1,200 lives.

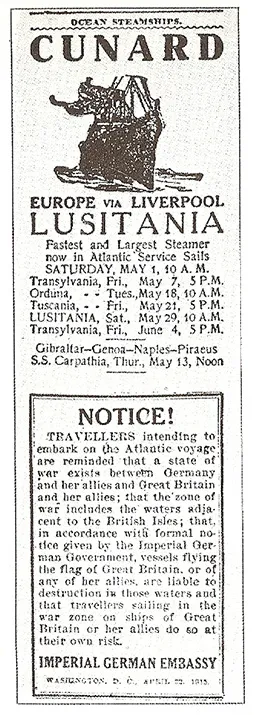

The Lusitania was not the first British ship to be torpedoed, and the German Navy had publicly vowed to destroy “every enemy merchant ship” it found in the waters surrounding Great Britain and Ireland. On the day the Lusitania set sail from New York, the German Embassy ran ads in U.S. newspapers, warning travelers to avoid liners flying the British flag. But in the case of the Lusitania the warnings went largely unheeded, due in part to the belief that the powerful ship could outrun any pursuant. The ship's captain, W. T. Turner, offered additional reassurance. “It's the best joke I've heard in many days this talk of torpedoing,” he supposedly told reporters.

England and Germany had been at war for close to a year by that point, but the United States, whose citizens would account for about 120 of the Lusitania’s victims, had remained neutral; ships sailing under the stars and stripes would not be the deliberate targets of German torpedoes. Though the U.S. didn’t officially enter the war until 1917, the sinking of the Lusitania, and the propaganda blitz that followed, proved a major factor in swaying public opinion in that direction.

Among the prominent American victims were such luminaries of the day as the theatrical impresario Charles Frohman, the popular writer Elbert Hubbard and the very rich Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt. But the list of passengers who missed the Lusitania’s last voyage was equally illustrious. Ironically, it wasn’t the fear of a German U-boat attack that kept most of them off the doomed liner but more mundane matters, such as unfinished business, an uncooperative alarm clock or a demanding mistress.

Here are the stories of eight famous men and women who were lucky enough to dodge the torpedo.

Arturo Toscanini

The conductor Arturo Toscanini was set to return to Europe aboard the Lusitania when his season at New York’s Metropolitan Opera ended. Instead, he cut his concert schedule short and left a week earlier, apparently aboard the Italian liner Duca degli Abruzzi. Contemporary newspaper accounts attributed his hasty departure to doctor’s orders. “His illness amounts practically to a nervous breakdown due to overwork during the season and also to excitement over the European war,” The New York Tribune reported.

In the years since, historians have offered other explanations, including the maestro’s battles with the Met’s management over budget cutbacks, a particularly bad performance of the opera Carmen and a recent ultimatum from his mistress, the singer and silent-movie actress Geraldine Farrar, that he leave his wife and family. Little wonder he set to sea.

Toscanini, who was then in his late 40s, lived for another four decades, until his death at age 89, in 1957. He recorded prolifically—an 85-disc boxed set released last year represents just a portion of his output—and became a celebrity in the U.S., conducting the NBC Symphony Orchestra on radio and later television. In 1984, a quarter-century after his death, he received a Grammy Award for lifetime achievement, sharing the honor that year with Charlie Parker and Chuck Berry.

Jerome Kern

Broadway composer Jerome Kern, then just 30 years old, supposedly planned to sail on the Lusitania with the producer Charles Frohman, but overslept when his alarm clock didn’t go off and missed the ship. The makers of the 1946 MGM musical biopic of Kern’s life, Till the Clouds Roll By, apparently didn’t consider that sufficiently dramatic, so the movie has Kern (played by Robert Walker) racing to the pier in a taxi and arriving just as the ship starts to pull away.

Kern would live for another three decades and write the music for such classics of the American songbook as “Ol’ Man River,” “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes,” and “The Way You Look Tonight.”

He died in 1945 at the age of 60 of a cerebral hemorrhage.

Isadora Duncan

With her latest tour of the United States just ended, the American-born dancer Isadora Duncan had a number of ships to choose from for her return to Europe, where she was then living, among them the Lusitania. Though she had crossed the Atlantic on the luxurious liner before, she passed it up this time in favor of the more humble Dante Alighieri, which left New York eight days later. One reason may have been money: Her tour had been a financial disaster.

In fact, Duncan’s creditors had threatened to seize her trunks and keep her from leaving the country at all until she paid about $12,000 in debts racked up during her visit. In a newspaper interview Duncan pleaded, “I appeal to the generosity of the American people and ask them if they are willing to see me and my pupils disgraced after all I have done in the cause of art.” Fortunately, within hours of the Dante’s departure, Duncan’s creditors had been placated and a benefactor had given her two $1,000 bills to buy the steamship tickets.

Several histories of the Lusitania disaster give the impression that Duncan sailed on the liner New York with Ellen Terry (see below). Though Duncan idolized the older actress and even had a child with her son, theater director Edward Gordon Craig, it seems to have been one of Duncan’s young dancers rather than Duncan herself who accompanied Terry.

Duncan mentions the Lusitania briefly in her autobiography: “Life is a dream, and it is well that it is so, or who could survive some of its experiences? Such, for instance, as the sinking of the Lusitania. An experience like that should leave for ever an expression of horror upon the faces of the men and women who went through it, whereas we meet them everywhere smiling and happy.”

A dozen years later, Duncan would have a famously fatal encounter with another form of transportation, strangled when her scarf became entangled in one of the wheels of a car in which she was riding.

Millicent Fenwick

A 5-year-old at the time of the disaster, Millicent Hammond Fenwick grew up to become an editor at Vogue, a civil rights activist, a Congresswoman from New Jersey and a possible inspiration for the famous “Doonesbury” character Lacey Davenport, whose outspokenness she shared.

Fenwick’s parents, Ogden and Mary Stevens Hammond, were both on board the Lusitania but left young Millicent and her siblings behind because their trip was humanitarian in nature rather than a family vacation, says Amy Schapiro, author of the 2003 biography Millicent Fenwick: Her Way. Her mother was headed to France to help establish a Red Cross hospital for World War I casualties.

Though they were warned not to take the Lusitania, Schapiro says, Millicent’s mother was determined to go and her father refused to let his wife sail alone. Her father survived the sinking; her mother did not. Perhaps because the subject was too painful, Fenwick rarely discussed her mother’s death or how the loss affected her, according to Schapiro.

Millicent Fenwick died in 1992 at age 82.

William Morris

The founder and namesake of what’s said to be the world’s oldest and largest talent agency, William Morris, born Zelman Moses, not only missed the Lusitania’s last voyage in 1915 but also the Titanic’s first and only attempt to cross the Atlantic three years earlier.

In both cases, Morris had booked passage but canceled at the last minute to attend to other matters, according to The Agency: William Morris and the Hidden History of Show Business by Frank Rose (1995). In those days, Morris’s business involved supplying vaudeville acts to thousands of live theaters across the United States. Among his clients were W.C. Fields, the Marx Brothers and Will Rogers, popular stage performers who would go on to become even bigger stars in the new media of movies and radio.

William Morris died of a heart attack in 1932, while playing pinochle.

Ellen Terry

Widely considered the greatest English actress of her day, Ellen Terry had finished an American lecture tour and was reportedly offered a free suite on the Lusitania for her return home. However, she had promised her daughter not to take an English ship because of war concerns, and instead booked passage on the American liner New York.

Though the New York was slower and considerably less comfortable than the Lusitania, Terry made the best of it. “I suppose on the whole I prefer this bed to the Ocean Bed,” she wrote in her diary.

Terry, who was 68 at the time, lived for another 13 years, during which she continued to perform and lecture as well as make several motion pictures.

William Gillette

The actor William Gillette often joined Charles Frohman on his trips to Europe and planned to accompany the producer aboard the Lusitania, according to Henry Zecher, author of the 2011 biography, William Gillette, America’s Sherlock Holmes. As Gillette later told the story, however, he had a commitment to perform in Philadelphia and was forced to stay behind.

Though little remembered now, Gillette was famed in his era as both a playwright and stage actor, especially for his portrayal of Sherlock Holmes. In fact, today’s popular image of Holmes may owe nearly as much to Gillette’s interpretation as to Arthur Conan Doyle’s original. It was Gillette, for example, who furnished Holmes with his trademark bent briar pipe, Zecher notes. Gillette also invented the line “Oh, this is elementary, my dear fellow,” which evolved into the immortal “Elementary, my dear Watson.”

The year after the Lusitania’s sinking, Gillette gave his one motion picture performance as Holmes. Unfortunately, the film, like many others of the silent era, seems to be lost.

Gillette died in 1937 at age 83. His eccentric and highly theatrical stone mansion in East Haddam, Connecticut, is now a tourist attraction, Gillette Castle State Park.

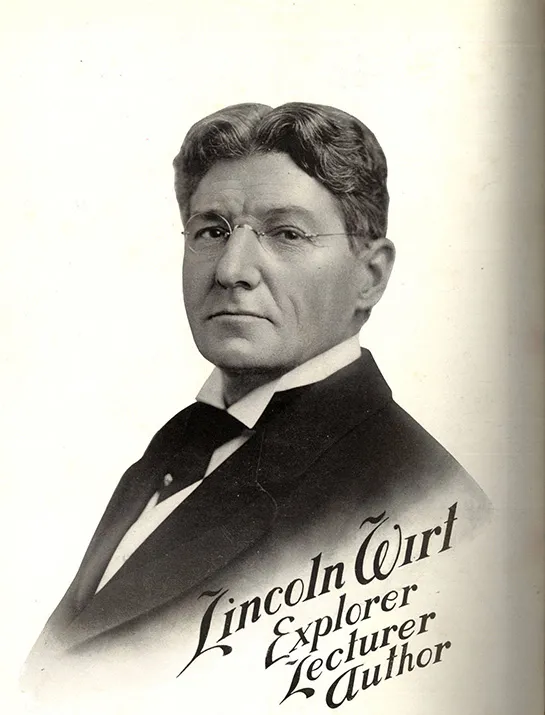

Lincoln Wirt

Probably the least famous person on our list by today’s standards, Lincoln Wirt was nationally known for his travel lectures, once a popular form of entertainment. At a time when few Americans could afford international travel and much of the planet remained exotic and unexplored, adventurers like Wirt brought the world to them. He was also a minister and war correspondent.

Wirt’s lecture “The Conquest of the Arctic,” for example, promised its audience an account of his 1,250-mile journey by canoe and dog sled, complete with “the horrors of scurvy, typhoid and freezing” along with “bubbling humor” and “descriptions of exquisite beauty.” But Wirt missed out on what might have been the tale of a lifetime when he reportedly cancelled his passage on the Lusitania in order to take another ship, the Canopic, and head to Constantinople.

Wirt’s adventures continued for another half century. He died in 1961, at the age of 97.

The Lusitania – Titanic connection

The sinking of the Lusitania in 1915 and the Titanic in 1912 may be forever linked as the two most famous maritime disasters of the 20th century. But the similarities between the Cunard liner Lusitania, launched in 1906, and the White Star liner Titanic, launched in 1911, hardly end here. Each was the largest ship in the world at the time of its debut, the Lusitania at 787 feet, the Titanic at 883 feet. They were also two of the most luxurious ships afloat, designed to compete for the rich and famous travelers of the day as well as for the profitable immigrant trade. In fact several notable passengers had ties to both ships:

• Al Woods, a well-known American theatrical producer, claimed to have had close calls with both the Lusitania and the Titanic, as did his frequent traveling companion, a businessman named Walter Moore. The two reportedly missed the Titanic when business matters kept them in London and called off their trip on the Lusitania because of fears of a submarine attack.

• The high-society fashion designer Lady Duff Gordon, among the most famous survivors of the Titanic disaster, was booked on the Lusitania but canceled her trip, citing health reasons.

• Two other Titanic survivors, banker Robert W. Daniel and his wife, Eloise, also appear to have canceled passage on the Lusitania, deciding to take an American ship, the Philadelphia, instead. Eloise Daniel lost her first husband in the Titanic disaster and met her future mate when he was pulled aboard the lifeboat she was in. They married two years later. Interviewed on their arrival in London, he described the crossing on the Philadelphia as “absolutely uneventful.”

• Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt, 37-year-old railroad heir and horse fancier, missed the Titanic in 1912 but unfortunately not the Lusitania in 1915, despite receiving a mysterious telegram telling him the ship was doomed. Vanderbilt died a hero in the disaster, reportedly giving his lifebelt to a young woman passenger, even though he couldn’t swim.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/greg2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/greg2.png)