A Civil Rights Watershed in Biloxi, Mississippi

Frustrated by the segregated shoreline, black residents stormed the beaches and survived brutal attacks on “Bloody Sunday”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/black-and-white-demonstrators-Biloxi-beach-631.jpg)

The waters beside Biloxi, Mississippi, were tranquil on April 24, 1960. But Bishop James Black’s account of how the harrowing hours later dubbed “Bloody Sunday” unfolded for African-American residents sounds eerily like preparations taken for a menacing, fast-approaching storm. “I remember so well being told to shut our home lights off,” said Black, a teenager at the time. “Get down on the floor, get away from the windows.”

It wasn’t a rainstorm that residents battened down for, but mob reprisals. Hours earlier Black and 125 other African-Americans had congregated at the beach, playing games and soaking sunrays near the circuit of advancing and retreating tides. This signified no simple act of beach leisure, but group dissent. At the time, the city’s entire 26-mile-long shoreline along the Gulf of Mexico was segregated. Led by physician Gilbert Mason, the black community sought to rectify restricted access by enacting a series of “wade-in” protests. Chaos and violence, though, quickly marred this particular demonstration.

To comprehend how a beautiful beachfront became a laboratory for social unrest, consider Dr. Mason’s Biloxi arrival in 1955. A Jackson, Mississippi native, the general practitioner moved with his family after completing medical studies at Howard University and an internship in St. Louis. Many of Biloxi’s white doctors respected Mason, who died in 2006. “Some would ask him to scrub in for surgeries,” said his son, Dr. Gilbert Mason Jr. Still, gaining full privileges at Biloxi Hospital took 15 years. In northern cities, he’d dined at lunch counters and attended cinemas alongside whites. Here, change lagged. “Dad was not a traveled citizen, but he was a citizen of the world,” his son noted. “Things that he barely tolerated as a youth, he certainly wasn’t going to tolerate as an adult.”

Chief among those was the coastline’s inequity of access. In the early 1950s, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers fortified the beach to stem seawall erosion. Though the project employed taxpayer funds, blacks were relegated to mere swatches of sand and surf, such as those beside a VA Hospital. Homeowners claimed the beaches as private property—a view Mason vigorously disputed. “Dad was very logical,” said Mason Jr. “He approached it systematically.”

This approach represented the doctor’s modus operandi, according to NAACP Biloxi Branch President James Crowell III, who was mentored by Mason. “The thing that amazed me about Dr. Mason was his mind,” said Crowell. “His ability to think things through and be so wise: not only as a physician, but as a community leader.”

While making a mark in medicine, Mason engaged in political discourse with patients, proposing ways they might support the still-nascent civil rights struggle. A scoutmaster position brought him in contact with adolescents looking to lend their labor. These younger participants included Black and Clemon Jimerson, who had yet to turn 15 years old. Still, the injustice Jimerson endured dismayed him. “I always wanted to go on the beach, and didn’t know why I couldn’t,” he said. “Whenever we took the city bus, we had to enter through the front door and pay. Then we had to get off again, and go to the back door. We couldn’t just walk down the aisle. That worried and bothered me.”

For Jimerson, the protest was a family affair: his mother, stepfather, uncle and sister took part, too. Jimerson was so ebullient about participating, he purchased an ensemble for the occasion: beach shoes, bright shirt and an Elgin watch.

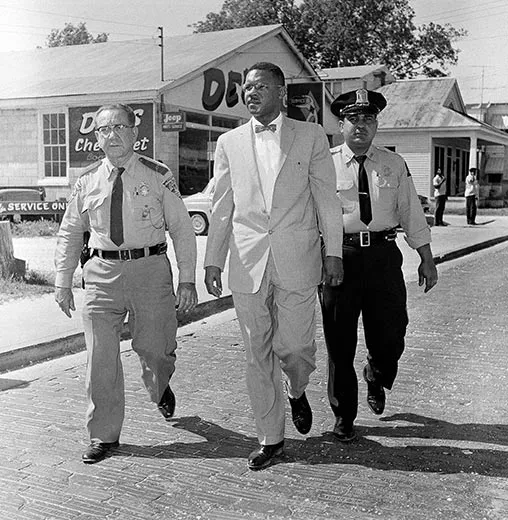

Low attendance at the initial protest on May 14, 1959, wade-in hardly suggested a coming groundswell. Still, Mason Jr. noted: “Every wade-in revealed something. The first protest was to see what exactly would be the true police response.” The response was forcible removal of all nine participants, including both Masons. Mason Sr. himself was the lone attendee at the second Biloxi protest—on Easter 1960, a week before Bloody Sunday, and in concert with a cross-town protest led by Dr. Felix Dunn in neighboring Gulfport. Mason’s Easter arrest roused the community into a more robust response.

Before the third wade-in, Mason directed protesters to relinquish items that could be construed as weapons, even a pocketbook nail file. Protesters split into groups, stationed near prominent downtown locales: the cemetery, lighthouse and hospital. Mason shuttled between stations, monitoring proceedings in his vehicle.

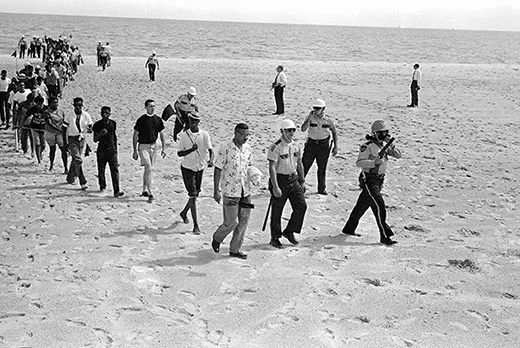

Some attendees, like Jimerson, started swimming. The band of beachgoers held nothing but food, footballs, and umbrellas to shield them from the sun’s glint. Wilmer B. McDaniel, operator of a funeral home, carried softball equipment. Black and Jimerson anticipated whites swooping in—both had braced for epithets, not an arsenal. “They came with all kinds of weapons: chains, tire irons,” said Black, now a pastor in Biloxi. “No one expected the violence that erupted. We weren’t prepared for it. We were overwhelmed by their numbers. They came like flies over the area.”

One member of the approaching white mob soon struck McDaniel—the opening salvo in a brutal barrage. “I saw McDaniel beaten to within an inch of his life,” said Black. “He fell, and was hit with chains, and the sand became bloody.” As the attack persisted, McDaniel’s pleading wife shielded his body with hers.

As the mob pursued Jimerson across the highway, where traffic had all but halted, he heard a white adult urge his assailant, “You better catch that nigger. You better not let him get away.” In one terrifying moment, Jimerson didn’t think he would. Heading toward an unlikely sanctuary—houses dating back to before the Civil War on the highway’s other side —a fence blocked Jimerson’s route, one he knew he couldn’t scale. “There was nothing I could do. I said my prayer and balled my fist.” He swung and missed, but the attempt made him tumble, and sent his would-be combatants scattering.

After the melee, Dr. Mason treated injured patients. Jimerson searched with his stepfather for his newly purchased ensemble, only to find it part of a pyre, burning within a white column of smoke. “Son, I’ll tell you what,” Jimerson’s stepfather said. “We can get you another watch. We can’t get you another life.”

When night fell, riots rose up. White mobs rolled through black neighborhoods, issuing threats and firing guns. Former Mississippi Governor William Winter, who served as state tax collector at the time, recalls feeling “great admiration for the courage” of the protesters, dovetailing with “disappointment, even disgust, that a group of people would deny them access to the beach. Not only deny them access, but inflict physical violence.”

The event was galvanizing. One white merchant’s involvement in the assaults galled the community, triggering a boycott of his store located in Biloxi’s African-American section. “This man was part of the gang, beating on us,” said Black. “And he still had the audacity to come back the next evening, and open his store.” Not for long: the boycott forced him to shutter his business.

A Biloxi NAACP branch formed swiftly after Bloody Sunday, with Mason installed as president, a title he held for 34 years. An October letter to Mason from Medgar Evers suggests the tipping point this protest represented: “If we are to receive a beating,” wrote Evers, “lets receive it because we have done something, not because we have done nothing.” A final wade-in followed Evers’ 1963 assassination, though the issue of beach access was only settled five years later, in federal court.

Though the wade-ins were sandwiched by the Greensboro lunch counter sit-ins and the famed Freedom Riders, the protests have gone largely unheralded, even though they served as a litmus test for future segregation challenges. Crowell, Mason’s handpicked successor as branch president, and a member of the NAACP’s national board of directors, believes the sheer volume of statewide dissent diminished the wade-ins notoriety. As he succinctly summarized: “Black people here in Mississippi were always involved in a struggle of some type.”

Current efforts have further commemorated this struggle. A historic marker, unveiled in 2009, honored “Bloody Sunday” and its hard-won achievement. The year prior, a stretch of U.S. Highway 90 was named after Mason. Governor Winter hopes the overdue recognition continues. “It is another shameful chapter in our past,” said Winter. “Those events need to be remembered, so that another generation—black and white—can understand how much progress we’ve made.”

Black echoed and extended this sentiment. “A price was paid for the privileges and rights we enjoy, and those that paid the price should be remembered.”