A Murder in Salem

In 1830, a brutal crime in Massachusetts riveted the nation—and inspired the writings of Edgar Allan Poe and Nathaniel Hawthorne

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Salem-murder-Richard-Crowninshield-portrait-631.jpg)

On the evening of April 6, 1830, the light of a full moon stole through the windows of 128 Essex Street, one of the grandest houses in Salem, Massachusetts. Graced with a beautifully balanced red brick facade, a portico with white Corinthian columns and a roof balustrade carved of wood, the three-story edifice, built in 1804, was a symbol of prosperous and proper New England domesticity. It was owned by Capt. Joseph White, who had made his fortune as a shipmaster and trader.

A childless widower, White, then 82, lived with his niece, Mary Beckford (“a fine looking woman of forty or forty-five,” according to a contemporary account), who served as his housekeeper; Lydia Kimball, a domestic servant; and Benjamin White, a distant relative who worked as the house handyman. Beckford’s daughter, also named Mary, had once been part of the household, but three years earlier she had married young Joseph Jenkins Knapp Jr., known as Joe, and now lived with him on a farm seven miles away in Wenham. Knapp was previously the master of a sailing vessel White owned.

That night, Captain White retired a little later than was his habit, at about 9:40.

At 6 o’clock the following morning, Benjamin White arose to begin his chores. He noticed that a back window on the ground floor was open and a plank was leaning against it. Knowing that Captain White kept gold doubloons in an iron chest in his room, and that there were many other valuables in the house, he feared that burglars had gained access to it. Benjamin at once alerted Lydia Kimball and then climbed the elegant winding stairs to the second floor, where the door to the old man’s bedchamber stood open.

Captain White lay on his right side, diagonally across the bed. His left temple bore the mark of a crushing blow, although the skin was not broken. Blood had oozed onto the bedclothes from a number of wounds near his heart. The body was already growing cold. The iron chest and its contents were intact. No other valuables had been disturbed.

I first read of the Salem murder many years ago in a Greenwich Village secondhand bookshop. I’d ducked inside to escape a sudden downpour, and as I scanned the dusty shelves, I discovered a battered, coverless anthology of famous crimes, compiled in 1910 by San Francisco police captain Thomas Duke.

The chapter on Captain White’s savage killing, evocative of the golden age mystery tales of the late 19th century, riveted me at once. The famed lawyer and congressman Daniel Webster was the prosecutor at the ensuing trial. His summation for the jury—its inexorable cadence, the slow gathering of dreadful atmospheric details—tugged at my memory, reminding me of Edgar Allan Poe’s tales of terror. In fact, after talking with Poe scholars, I learned that many of them agreed the famous speech had likely been the inspiration for Poe’s story “The Tell-Tale Heart,” wherein the narrator boasts of his murder of an elderly man. Moreover, I discovered, the murder case had even found its way into some of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s works, with its themes of tainted family fortunes, torrential guilt and ensuing retribution.

Those facts alone proved an irresistible magnet to a crime historian like me. But the setting—gloomy, staid Salem, where in the 1690s nineteen men and women were convicted of witchcraft and hanged—endowed the murder case with another layer of gothic intrigue. It almost certainly fed the widespread (and admittedly lurid) fascination with the sea captain’s death among the American public at the time. The town, according to an 1830 editorial in the Rhode Island American, was “forever...stained with blood, blood, blood.”

Soon after the discovery of the body, Stephen White—the murdered man’s nephew and a member of the Massachusetts legislature—sent for Samuel Johnson, a prominent Salem physician, and William Ward, Captain White’s clerk and business assistant. Ward made note of the plank at the open window, and near it he discovered two muddy footprints he believed had been made by the intruder. Decades before footprints were generally recognized as important evidence, Ward carefully covered them with a milk pan to shield them from the fine mist that had begun to fall. Meanwhile, Dr. Johnson’s cursory examination revealed the body was not quite cold; he concluded that death had occurred three to four hours earlier.

Dr. Johnson then performed an autopsy before a “coroner’s jury” comprised of local citizens, whose role was to assess the initial facts and determine whether a crime had taken place. In the jury’s presence, Johnson carefully examined the corpse, stripping off the shirt and inserting probes into some of the stab wounds to determine their depth and direction. He counted 13 stab wounds—“five stabs in the region of the heart, three in front of the left pap [nipple], and five others, still further back, as though the arm had been lifted up and the instrument struck underneath.” He attributed all the stab wounds to the same weapon, which suggested that there had been a single murderer. Though the wounds had oozed, there was no sign of spurting or spraying blood. Johnson interpreted this to mean that the blow to the head had come first, either killing White or stunning him, thereby slowing his circulation. Uncertain as to which of the many wounds was fatal, Johnson believed that a more complete autopsy was necessary.

This was performed on April 8, at 5:30 in the evening. Dr. Abel Peirson, a medical colleague, assisted Johnson. A second post-mortem as thorough as this one was unusual in early 19th- century criminal investigations. In 1830, forensic science was still largely a footnote in legal and medical texts. But thanks to increasingly rigorous anatomical studies in medical schools, there had been progress in identifying murder instruments based upon the nature of the wounds and determining which had been the most likely cause of death.

The surgeons agreed that the skull fracture was due to a single severe blow from a cane or bludgeon, and that at least some of the chest wounds were caused by a dirk (short dagger), the cross-guard of which had struck the ribs with enough force to break them. Peirson disagreed with Johnson’s initial assessment that there was likely only one assailant. A medical consensus was elusive, in part, because of the 36-hour interval between inquest and the second autopsy—which had allowed extensive post-mortem changes, affecting the appearance of the wounds, as had Johnson’s initial insertion of a probe.

Stephen White gave the Salem Gazette permission to publish the autopsy findings. “However revolting the subject may be,” the newspaper said, “we have deemed it our duty to lay before our readers every particle of authentic information we can obtain, respecting the horrible crime which has so shocked and alarmed our community.”

The possibility that more than one assailant might have been involved and that a conspiracy might be afoot fueled unease. Salem residents armed themselves with knives, cutlasses, pistols and watchdogs, and the sound of new locks and bolts being hammered in place was everywhere. Longtime friends grew wary of each other. According to one account, Stephen White’s brother-in-law, discovering that Stephen had inherited the bulk of the captain’s estate, “seized White by the collar, shook him violently in the presence of family” and accused him of being the murderer.

Town fathers attempted to calm matters by organizing a voluntary watch and appointing a 27-man Committee of Vigilance. Although not burdened by any experience in criminal investigation, its members were given the power to “search any house and interrogate every individual.” Members took an oath of secrecy and offered a $1,000 reward for information “touching [on] the murder.”

But the investigation went nowhere; the committee was confronted with a scenario of too many suspects and too little evidence. No one had made plaster casts of the incriminating footprints that Ward had carefully covered the morning of the murder. (By 1830, scientists and sculptors were using plaster casts for preserving fossil specimens, studying human anatomy and recreating famous sculptures—but the technique was not yet de rigueur in criminal investigations.)

Since nothing had been stolen, the assailant’s motive puzzled townspeople and authorities alike. But revenge was not out of the question. As many in Salem knew, Joseph White was hardly the “universally respected and beloved” old man one local newspaper described. A bit of a domestic tyrant, he was given to changing his will at a whim and using his large fortune as a weapon to enforce his wishes. When his pretty young grandniece Mary announced her engagement to Joe Knapp, the old man declared Joe a fortune hunter, and when the marriage went forward without his consent, White disinherited Mary and fired Knapp.

What’s more, White had been a slave trader. The ownership of slaves was abolished in Massachusetts in 1783 and the slave trade outlawed five years later. Yet White had boasted to Salem minister William Bentley in 1788 that he had “no reluctance in selling any part of the human race.” (In Bentley’s estimation, this “betray[ed] signs of the greatest moral depravity.”) In a water-stained letter written in 1789 that I found deep in the archives of the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, a sailor named William Fairfield, who served on the schooner Felicity, told his mother about a slave revolt that had killed the ship’s captain. Joseph White was one of the owners of the Felicity.

Some of White’s ships had engaged in legitimate trade, hauling everything from codfish to shoes. But many had sailed from Salem laden with tools and trinkets, to be traded in Africa for human cargo. Manacled and cramped into ghastly holds, many of the captives did not survive the voyage. Those who did were traded in the Caribbean for gold—enough to buy property, build a mansion and fill an iron chest.

“Many maritime families in Salem supported the slavery system in one way or another,” says Salem historian Jim McAllister. That was how they had built their fortunes and paid their sons’ Harvard tuitions. There was an understanding in Salem society that this shameful business was best not spoken of, particularly in Massachusetts, where antislavery sentiments ran high. “A few of our merchants, like others in various seaports, still loved money more than the far greater riches of a good conscience, more than conformity with the demands of human rights, with the law of the land and the religion of their God,” Salem minister Joseph B. Felt wrote in 1791.

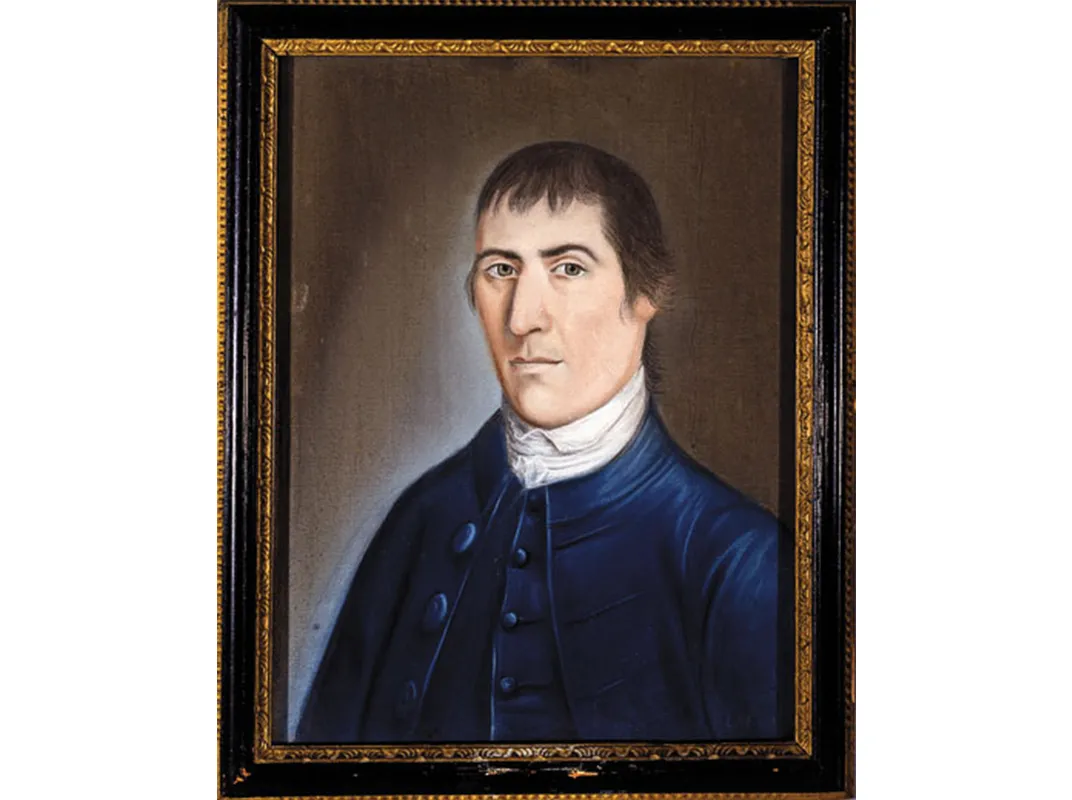

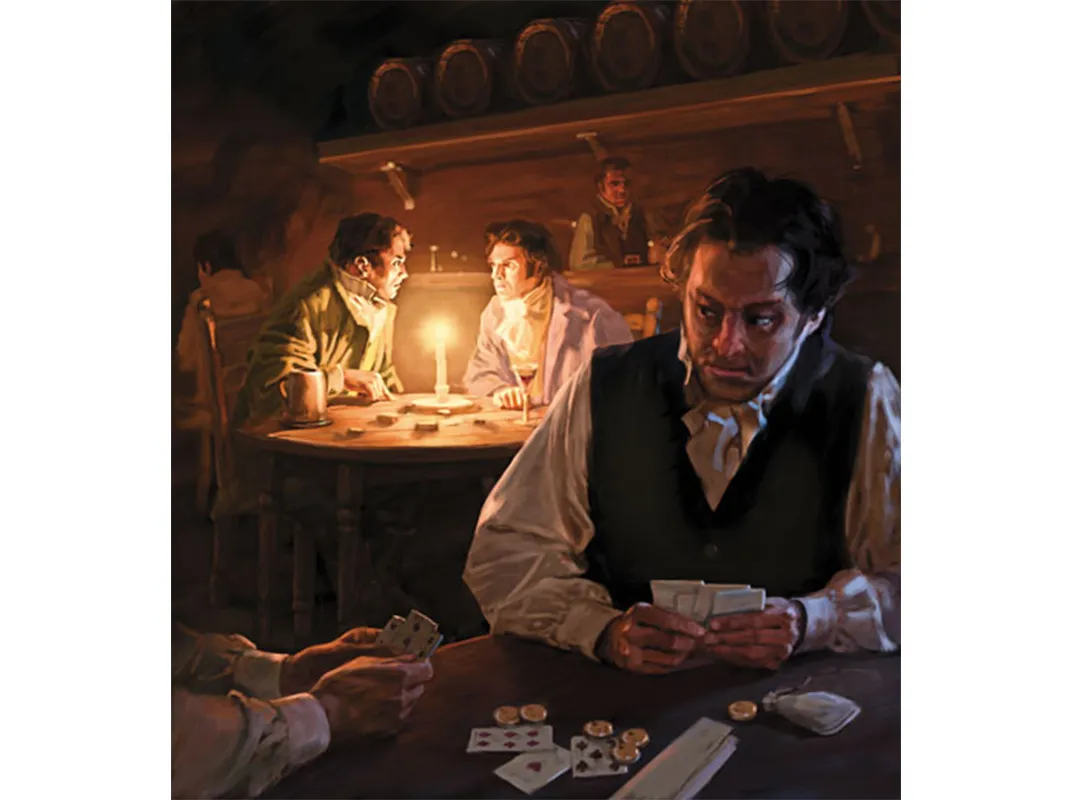

A little more than a week after the murder, Stephen White received a letter from a jailer 70 miles away in New Bedford. The letter said an inmate named Hatch, a petty thief, claimed he had crucial information. While frequenting gambling houses in February, Hatch had overheard two brothers, Richard and George Crowninshield, discussing their intent to steal Joseph White’s iron chest. The Crowninshield brothers were the disreputable scions of an eminent Salem family. Richard, according to court transcripts, was known to favor Salem’s “haunts of vice.” The town’s Committee of Vigilance brought Hatch in chains to testify before a Salem grand jury. On May 5, 1830, the jury indicted Richard Crowninshield for murder. His brother George—and two other men who were in his company at the gambling house—were charged with abetting the crime. All were detained in the Salem Gaol, a grim edifice of granite blocks, iron-barred windows and brick-walled cells.

Then, on May 14, Joseph Knapp Sr., the father of the man who had married White’s disinherited grandniece, received a letter from Belfast, Maine. It demanded a “loan” of $350, and threatened disclosure and ruin if this were not promptly paid. It was signed “Charles Grant.”

The senior Knapp could make no sense of the matter and asked his son for advice. It’s “a devilish lot of trash,” Joe Knapp Jr. told his father and advised him to give it to the committee.

The Committee of Vigilance pounced on the letter. It sent $50 anonymously to Grant at his local post office, with a promise of more to come, and a man was dispatched to apprehend whoever collected the money. The recipient turned out to be John C.R. Palmer. Arrested as a possible accessory to the murder, but promised immunity for his testimony, he told a complex tale: during a stay at the Crowninshield family home, Palmer had overheard George tell Richard that John Francis (“Frank”) Knapp, a son of Joseph Knapp Sr., wanted them to kill Captain White—and that Joe Jr., Frank’s brother, would pay them $1,000 to commit the crime. The Committee of Vigilance promptly arrested the Knapp brothers and sent them to the Salem Gaol, their cells not far from those occupied by the Crowninshields.

At first, Richard Crowninshield exuded a sense of rectitude, certain that he would be found innocent. During his imprisonment, he asked for books on mathematics and Cicero’s Orations, and conveyed nonchalance—until the end of May, when Joe Knapp confessed to his role in the murder plot.

The confession was given to the Rev. Henry Colman, an intimate friend of the White family. Colman also had close connections to the Committee of Vigilance, and in this role had promised Joe immunity from prosecution in exchange for his testimony.

The nine-page confession—in Colman’s handwriting but signed by Knapp—began, “I mentioned to my brother John Francis Knapp, in February last, that I would not begrudge one thousand dollars that the old gentleman, meaning Capt. Joseph White of Salem, was dead.” It went on to explain that Joe Knapp believed if Captain White died without a legal will, his fortune would be divided among his close relatives, giving Mary Beckford, Knapp’s mother-in-law, a considerable fortune.

To this end, Joe opened Captain White’s iron chest four days before the murder and stole what he erroneously believed to be the old man’s legal will. The true last will of Joseph White, favoring his nephew Stephen, was safely in the office of the dead man’s lawyer. But Joe was unaware of this fact. He hid the document in a box he covered with hay and burned the stolen paper the day after the murder.

Joe and Frank had debated how to commit the murder. They considered ambushing White on a road or attacking him in his house. Frank, however, told Joe that “he had not the pluck to do it,” and suggested hiring Richard and George Crowninshield, whom the Knapp brothers had known since adolescence.

After several meetings, the Knapps and the Crowninshields gathered at the Salem Common at 8 p.m. on April 2 to finalize the plan. Richard, Joe confessed, had thoughtfully displayed the “tools” he planned to use for the project. Using his machinist’s skills, he had manufactured one of the murder weapons—a club—himself. It was “two feet long, turned of hard wood...and ornamented...with beads at the end to keep it from slipping....The dirk was about five inches long on the blade...sharp at both edges, and tapering to a point.”

That same evening, after stealing what he believed to be the will, Joe Knapp “unbarred and unscrewed” a window in Captain White’s house. Four days later, at 10 p.m., Richard Crowninshield entered the front yard through the garden gate and climbed through the unlocked window to murder White.

The detailed confession pointed to Richard Crowninshield as the principal perpetrator of the deed: he would surely hang. But Richard learned from defense attorney Franklin Dexter that Massachusetts law did not allow the trial of an accessory to a crime unless the principal had first been tried and convicted. Richard must have seen a way to exercise his ingenuity one last time and perhaps save his brother and friends. On June 15, at 2 in the afternoon, a jailer found Richard’s body hanging by its neck from two silk handkerchiefs tied to the bars of his cell window.

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts, it seemed, had been cheated out of an open-and-shut case, unless the state could find a legal basis for putting the other three men on trial. Newspaper reporters descended on Salem from as far away as New York City—ostensibly with the lofty goal of ensuring that justice be achieved. In the words of pioneering journalist James Gordon Bennett, then a correspondent for the New York Courier: “The press is the living jury of the Nation!”

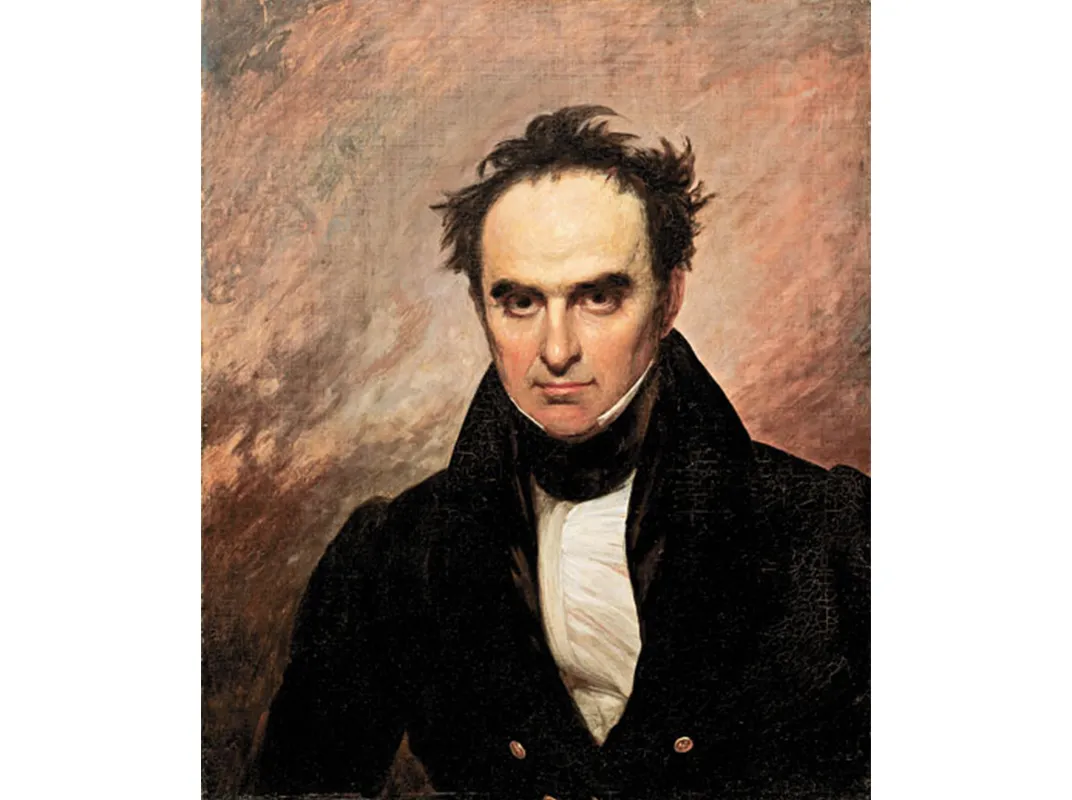

The prosecution in the White case faced a quandary. Not only was there no prior conviction of the principal (due to Richard Crowninshield’s suicide), but Joe Knapp was refusing to testify and uphold his confession. So the prosecution turned to Senator Daniel Webster of Boston, the New Hampshire-born lawyer, lawmaker and future secretary of state, perhaps best remembered for his efforts to hammer out compromises between Northern and Southern states that he believed would forestall civil war.

Webster, then 48, had served several terms in the House of Representatives before being elected to the U.S. Senate in 1827. He was a close friend of such Salem area notables as Stephen White and Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story. Webster’s commanding presence, his dramatic dark coloring and his relentless gaze had earned him the sobriquet “Black Dan.” In the courtroom he was known to be fierce at cross-examination and riveting at summation—“the immortal Daniel,” the New Hampshire Patriot and States Gazette had called him.

Asked by Stephen White to aid prosecutors at the murder trial, Webster was torn. Throughout his lengthy legal career, he had always stood for the defense. A large part of his reputation rested on his passionate oratory on behalf of the accused. Further, his personal connections with the victim’s friends and relatives raised delicate issues of legal ethics.

On the other hand, if he stood by his friends, the favor would someday be repaid. Then there was the handsome fee of $1,000 that Stephen White had discreetly arranged for his services. Webster, a heavy drinker who had a tendency to spend beyond his means and was chronically in debt, agreed to “assist” the prosecution—which meant, of course, that he would lead it.

The accused men had chosen to be tried separately, and the first to come to trial, in August 1830, was Frank Knapp. Interest ran high. Bennett reported that the crowds trying to enter the courtroom to see Webster were “like the tide boiling up on the rocks.” With Richard Crowninshield dead—“There is no refuge from confession but suicide, and suicide is confession,” Webster famously said—Webster’s intent was to establish Frank Knapp as a principal rather than an accessory. Several witnesses testified they had seen a man wearing a “camlet cloak” and a “glazed cap,” such as Frank often wore, late on the night of the murder, on Brown Street, behind the White property. Webster argued that Frank was there to give direct aid to the murderer, and was therefore a prime actor. The defense challenged the witnesses’ identification and scoffed that Frank’s mere presence on Brown Street could have provided vital aid. The jury deliberated for 25 hours before announcing they were deadlocked. The judge declared a mistrial. The case was scheduled to be retried two days later.

The second trial brought debate over the forensic evidence to the fore. In the first trial, only Dr. Johnson had testified. But this time the prosecution included the formal testimony of Dr. Peirson. His dissenting opinion on the autopsy—that there possibly had been two assailants—had been widely read in the Salem Gazette. Now Peirson was being used as an expert witness in an apparent attempt to cast doubt on the theory that Richard Crowninshield had acted alone in the lethal assault upon Joseph White. Webster speculated that Knapp might have delivered the “finishing stroke;” or that the other wounds had been inflicted “from mere wantonness.” Knapp’s defense attorney ridiculed the argument, wondering aloud why Knapp would return to the house to stab a dead body: “Like another Falstaff did he envy the perpetrator the glory of the deed and mean to claim it as his own?”

In the interim between the two trials, the new jury had been exposed to newspaper accounts of the first hearing, as well as to heavy criticism leveled at the previous jury for its failure to convict. Thus encouraged, the second jury listened intently as Webster captivated the courtroom with a dramatic re-creation of the crime: “A healthful old man, to whom sleep was sweet, the first sound slumbers of the night held him in their soft but strong embrace. The assassin enters, through the window already prepared . . . With noiseless foot he paces the lonely hall, half-lighted by the moon; he winds up the ascent of the stairs, and reaches the door of the chamber. Of this, he moves the lock, by soft and continued pressure, till it turns on its hinges without noise; and he enters, and beholds his victim before him....”

Webster’s summation was later deemed a masterpiece of oratory. “The terrible power of the speech and its main interest lie in the winding chain of evidence, link by link, coil by coil, round the murderer and his accomplices,” British literary critic John Nichol wrote. “One seems to hear the bones of the victim crack under the grasp of a boa-constrictor.” Samuel McCall, a prominent lawyer and statesman, called the speech “the greatest argument ever addressed to a jury.”

After just five hours of deliberation the jury accepted Webster’s contention that Frank Knapp was a principal to the crime and convicted him of murder.

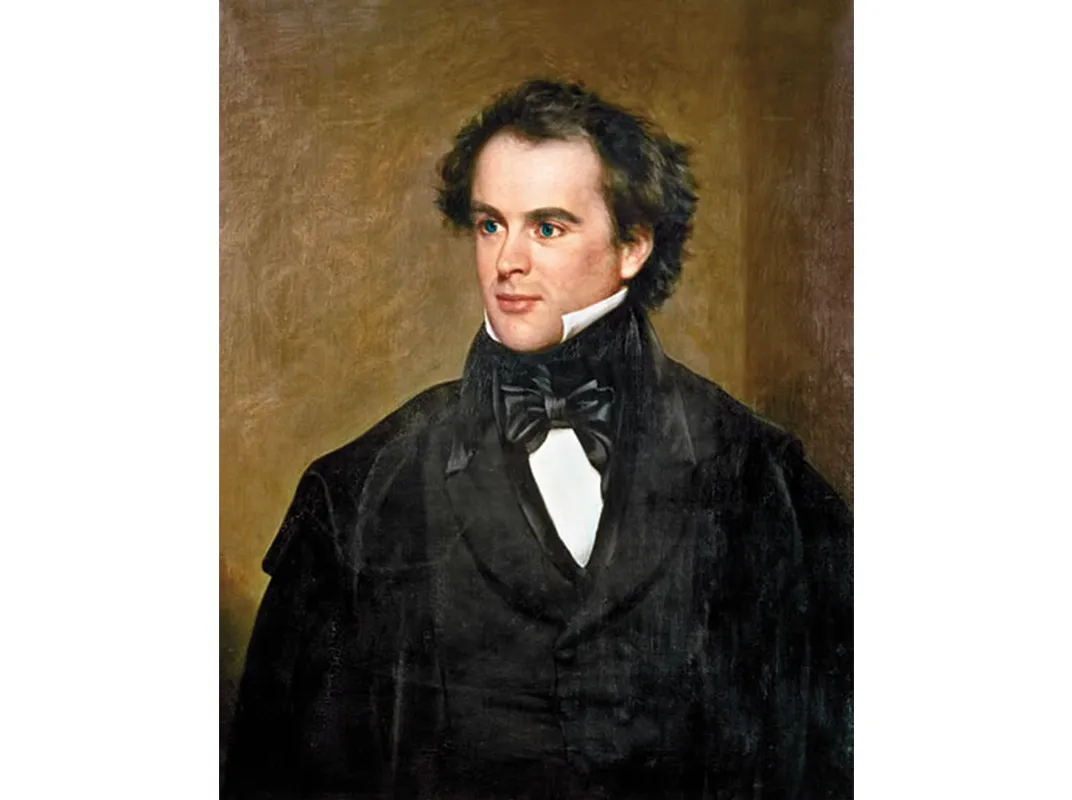

“The town now begins to grow rather more quiet than it has been since the murder of Mr. White,” Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote in a letter to a cousin, “but I suppose the excitement will revive at the execution of Frank Knapp.”

Hawthorne, a still-struggling, 26-year-old writer living in his mother’s home in Salem, was riveted by the case. The son and grandson of respected sea captains, he was also a descendant of John Hathorne, one of the infamous hanging judges of the witchcraft trials. The family connection both fascinated and repelled the future novelist, and no doubt informed his lifelong interest in crime and inherited guilt. At the time of the Knapp trial, Hawthorne was writing short fiction for local papers, including the Salem Gazette, which covered the story assiduously. Some scholars have suggested that Hawthorne wrote some of the newspaper’s unsigned articles about the murder, though there is no hard evidence to support that.

In letters, Hawthorne described the town’s “universal prejudice” against the Knapp family and expressed his own ambivalence about the jury’s verdict: “For my part, I wish Joe to be punished, but I should not be very sorry if Frank were to escape.”

On September 28, 1830, before a crowd of thousands, Frank Knapp was hanged in front of Salem Gaol. His brother Joseph, tried and convicted in November, met the same fate three months later. George Crowninshield, the remaining conspirator, had spent the night of the murder with two ladies of the evening, who provided him with an alibi. After two trials he was acquitted by a now-exhausted court. The two men who had been in the company of George in the gambling house were discharged without trial.

By September 9, 1831, Hawthorne was writing to his cousin that, “The talk about Captain White’s murder has almost entirely ceased.” But echoes of the trial would reverberate in American literature.

Two decades later, Hawthorne found inspiration in the White murder in writing The Scarlet Letter (1850). Margaret Moore—the former secretary of the Nathaniel Hawthorne Society and the author of The Salem World of Nathaniel Hawthorne—argues that Webster’s ruminations on the uncontrollable urge to confess influenced Hawthorne’s portrayal of the Rev. Arthur Dimmesdale in The Scarlet Letter. Dimmesdale is tortured by the secret of being the lover of Hester Prynne—and when Hester hears Dimmesdale’s final sermon, Hawthorne writes, she could detect “the complaint of the human heart, sorrow-laden, perchance guilty, telling its secret, whether of guilt or sorrow, to the great heart of mankind; beseeching its sympathy or forgiveness—at every moment—in each accent....”

The late Harvard University literary scholar Francis Otto Matthiessen argued that echoes of the White murder and Webster’s summation also found their way into The House of Seven Gables (1851). The opening chapter sets the gothic tone by describing the Pyncheon family’s sordid history—the murder 30 years prior of the family patriarch, “an old bachelor and possessed of great wealth in addition to the house and real estate.” Later in the novel, Hawthorne devotes 15 pages to an unnamed narrator who describes and taunts the corpse of the tyrannical Judge Pyncheon. Matthiessen saw Webster’s influence particularly in the way Hawthorne used the imagery of moonlight: “Observe that silvery dance upon the upper branches of the pear-tree, and now a little lower, and now on the whole mass of boughs, while, through their shifting intricacies, the moonbeams fall aslant into the room. They play over the Judge’s figure and show that he has not stirred throughout the hours of darkness. They follow the shadows, in changeful sport, across his unchanging features.”

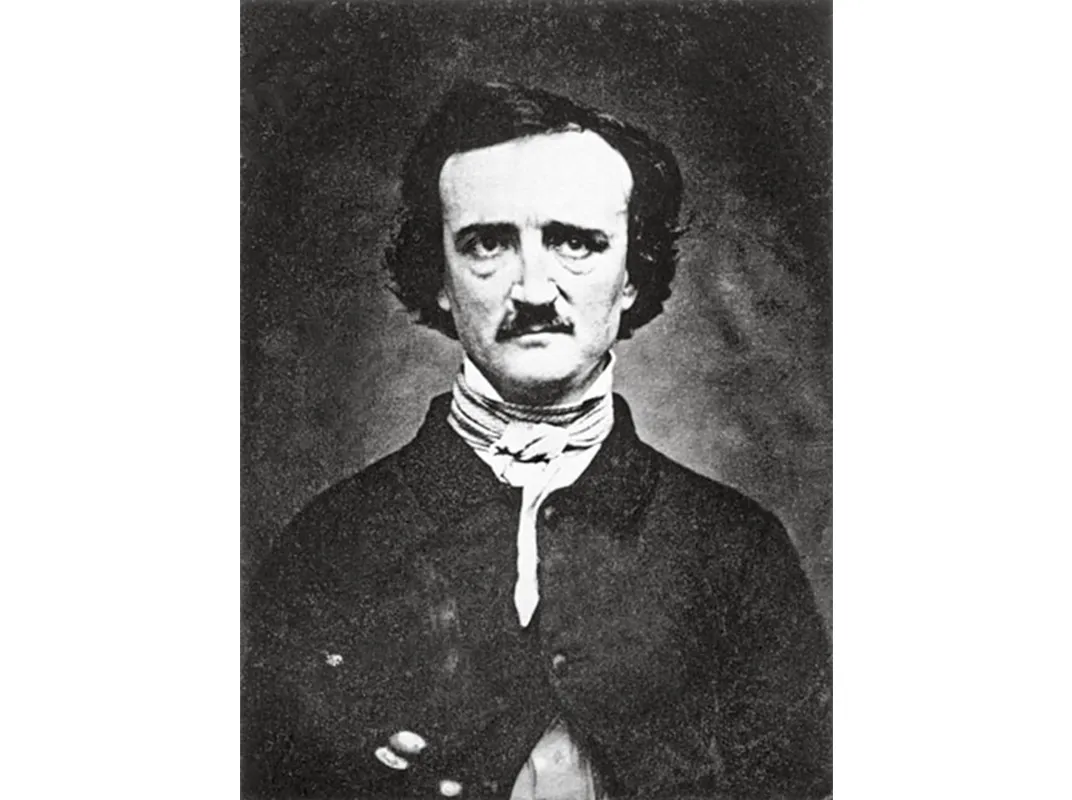

The White murder also left its mark on Edgar Allan Poe, who at the time of the crime was poised to enter the U.S. Military Academy at West Point (which he left after one year by deliberately getting court-martialed for disobedience). Nobody knows if Poe followed the trial as it occurred, but by 1843, when he published “The Tell-Tale Heart,” he had clearly read about it. Poe scholar T. O. Mabbott has written that Poe relied critically on Webster’s summation in writing the story. At the trial, Webster spoke of the murderer’s “self-possession” and “utmost coolness.” The perpetrator, he added, ultimately was driven to confession because he believed the “whole world” saw the crime in his face and the fatal secret “burst forth.” Likewise, Poe’s fictional murderer boasts of “how wisely” and “with what caution” he killed an old man in his bedchamber. But the perfect crime comes undone when Poe’s murderer—convinced that the investigating police officers know his secret and are mocking him—declares, “I felt that I must scream or die!...I admit the deed!”

The spellbinding summation Daniel Webster delivered at the trial was printed as part of an anthology of speeches later that year and sold to an admiring public. But Black Dan’s political ambitions took a turn for the worse in 1850 when, belying his years of opposition to slavery, he gave an impassioned speech defending the new Fugitive Slave Act, which required Northern states to aid in the return of escaped slaves to their Southern masters. The legislation was part of a compromise that would allow California to be admitted to the Union as a “free state.” But abolitionists perceived the speech as a betrayal and believed it to be an attempt by Webster to curry favor with the South in his bid to become the Whig Party’s presidential candidate in 1852, and he lost the nomination. Webster died shortly thereafter from an injury resulting from a carriage accident. The autopsy revealed the cause of death to be a brain hemorrhage, complicated by cirrhosis of the liver.

For its part, Salem would become an important center of antislavery activism. Prior to Frederick Douglass’ emergence as a national figure in the 1840s, Salem native Charles Lenox Remond was the most famous African-American abolitionist in the United States and Europe. His sister, Sarah Parker Remond, also lectured abroad, and often shared the podium with Susan B. Anthony at antislavery conventions.

Salemites would make every effort to put the White murder behind them. Even a century after the trial, the town was reluctant to speak of it. Caroline Howard King, whose memoir When I Lived in Salem appeared in 1937, destroyed the chapter about the crime before publication, judging it to be “indiscreet.” In 1956, when Howard Bradley and James Winans published a book about Webster’s role in the trial, they initially encountered resistance when conducting their research. “Some people in Salem preferred to suppress all reference to the case,” Bradley and Winans wrote, and “there were still people who viewed inquiries about the murder with alarm.”

Today, the Salem witch trials drive the town’s tourist trade. But, every October, you can go on historian Jim McAllister’s candlelight “Terror Trail” tour, which includes a stop at the scene of the crime, now known as the Gardner-Pingree House. You can also tour the inside of the house—a national historic landmark owned by the Peabody Essex Museum—which has been restored to its 1814 condition. The museum possesses—but doesn’t exhibit—the custom-made club that served as the murder weapon.

I was allowed to inspect it, standing in a cavernous storage room wearing a pair of bright blue examination gloves. The club is gracefully designed and fits easily in the hand. I couldn’t help but admire Richard Crowninshield’s workmanship.

Crime historian E.J. Wagner is the author of The Science of Sherlock Holmes. Chris Beatrice is a book and magazine illustrator who lives in Massachusetts.