A Photo-Journalist’s Remembrance of Vietnam

The death of Hugh Van Es, whose photograph captured the Vietnam War’s end, launched a “reunion” of those who covered the conflict

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Indelible-Saigon-rooftop-631.jpg)

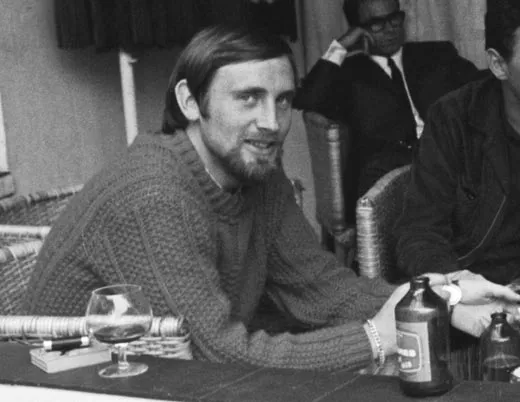

The end was at hand. Saigon swirled with panicked mobs desperate to escape. On the outskirts of the surrounded city, more than a dozen North Vietnamese divisions prepared for their final assault. A Dutch photographer, Hugh Van Es, slipped through the crowds that day, snapping pictures, then hurried down Tu Do Street to the United Press International office to develop his film.

No sooner had he ensconced himself in the darkroom than a colleague, Bert Okuley, called out from an adjoining room, "Van Es, get out here! There's a chopper on that roof!" He pointed to an apartment building four blocks away, where an Air America Huey, operated by the CIA, was perched. Twenty-five or so people were scaling a makeshift ladder, trying to clamber aboard.

Van Es slapped a 300-mm lens on his Nikon and took ten frames from the tiny balcony near Okuley's desk. The chopper lifted off, overloaded with about 12 evacuees. Those left behind waited for hours for the helicopter to return. It never did. But all that day—April 29, 1975—and into the evening, the sky was alive with choppers darting to at least four pickup sites in what was to be the largest helicopter evacuation in history.

During his seven years in Vietnam, Van Es had taken dozens of memorable combat pictures, but it was this one hurried shot from the balcony that brought him lifelong fame and became the defining image of the fall of Saigon, and the tumultuous end of the Vietnam War. Though it has been reprinted thousands of times since (often misidentified as an evacuation from the roof of the U.S. Embassy), his only payment was a one-time $150 bonus from UPI, which owned the photo rights.

"Money, or the lack of, never bothered Hugh," says Annie Van Es, his wife for 39 years. "Photography was his passion, not dollars." When a South Vietnamese photographer he knew inexplicably claimed authorship of the photograph years later, she says, Van Es' reaction was: "He is having a hard time in communist Saigon and needs to make a living; I can't blame him." Van Es looked up his old friend on a return trip to what had been renamed Ho Chi Minh City and never brought up the appropriation.

After the war, Van Es returned to Hong Kong to freelance. When he wasn't off covering conflicts in Bosnia, Afghanistan or the Philippines, friends could find him holding court at the Foreign Correspondents Club (FCC) bar in Hong Kong, swearing like a sailor, tossing down beers, smoking unfiltered cigarettes and telling war stories with caustic humor.

Last May, at age 67, Van Es suffered a brain hemorrhage and lay unconscious for a week in a Hong Kong hospital. Derek Williams, a CBS sound man during the war, put out the word over a voluminous correspondents' e-mail list so Annie wouldn't have to supply his many friends and colleagues with daily updates. Vietnam-era journalists chimed in with comments of encouragement, hitting the "reply to all" button. Soon people who hadn't been in touch since bonding on jungle battlefields a generation ago started corresponding.

Thus was born a members-only Google discussion group, "Vietnam Old Hacks," to share madcap remembrances, to argue about history and where to get the best pho ga (chicken noodle broth), to reflect on former Defense Secretary Robert McNamara's death, to find out who among their fraternal gang is dead and who is still alive. Plans are underway for a real-life reunion in Vietnam next April. Seventy of the 200-plus members say they plan to attend.

"Jeez, we've certainly gone our own way for all these years, but then—bang!—we're all back together again," says Carl Robinson, a wartime Associated Press reporter and photo editor.

Like Van Es, many of us who covered the war found ourselves forever in the grip of Vietnam. No other story, no other war, quite measured up. The exotic charm and dangerous undercurrents of Saigon were seductive, the adrenaline rush of survival intoxicating. We hitchhiked around the country on military helicopters and roamed the battlefields without censorship. The Associated Press lists 73 of our colleagues as killed in South Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos, yet as individuals we felt invulnerable.

"I've searched for an answer why I stayed all those years," says George Esper, an AP reporter who spent nearly a decade in Vietnam. "What I keep coming back to was a young nurse from upstate New York I saw on a firebase. It was monsoon season. We were under rocket attack. She was tending the badly wounded. Some died in her arms. And I said, ‘Wow. What a woman! Why are you here?' and she said, ‘Because I've never felt so worthwhile in my life.' That's how I felt, too."

"Did Vietnam teach me anything professionally?" says Loren Jenkins, a wartime reporter for Newsweek who is now the foreign editor of National Public Radio. "Absolutely. It taught me never to believe an official. It made me a terrific skeptic."

"I honestly believe those years gave [Hugh] the best memories and most meaning to his life," his wife said after he died in the Hong Kong hospital, never having regained consciousness. The FCC set up a "Van Es Corner" in the bar with a display of his Vietnam photographs. Nearby is a small plaque marking where his colleague and drinking buddy Bert Okuley had a fatal stroke in 1993, a double Jack Daniels in hand. For her part, Annie honored only one of Van Es' two requests for his exit: his wake at the FCC was indeed boisterous and celebratory, but his coffin was not on display and did not serve as the bar.

David Lamb covered Vietnam for UPI and the Los Angeles Times. He is the author of Vietnam, Now (2003).