The American at the Battle of Waterloo

The British remember William Howe De Lancey, an American friend to the Duke of Wellington, as a hero for the role he played in the 1815 clash

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/45/10/4510024d-1b51-43a2-9015-3092e8ca8a1b/ih187935.jpg)

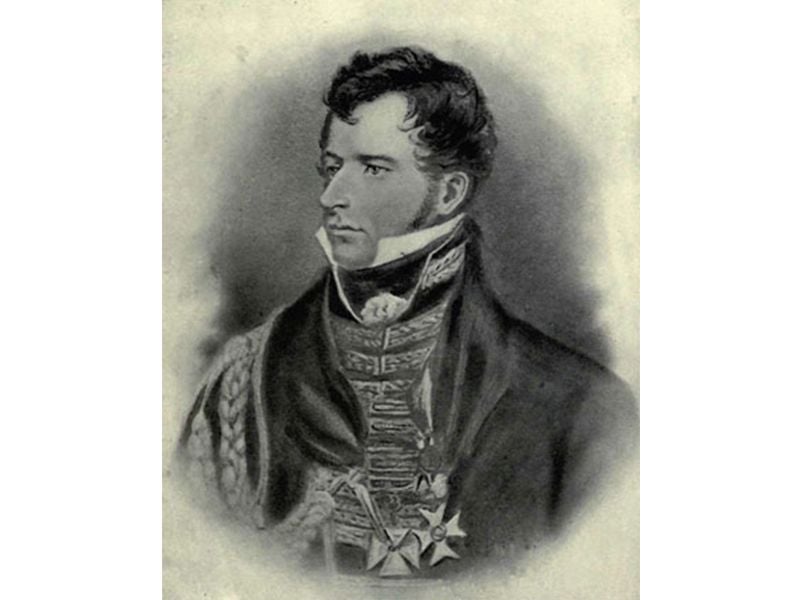

They called him “the American,” and while it’s unclear whether that was a term of endearment, any fellow British officer using it to disparage Col. William Howe De Lancey risked the wrath of his longtime friend and mentor, Arthur Wellesley—better known as the Duke of Wellington.

De Lancey was at Wellington’s side on the day of his greatest triumph—June 18, 1815, the Battle of Waterloo. The duke survived; the American didn’t.

Struck by a cannonball, and nursed at the front by his bride of just two months, De Lancey died a few days after the battle. Thanks in part to her best-selling account of her experience (which is being republished to coincide with the bicentennial of the battle), he is remembered today in Britain as one of the great martyrs of that epic day.

Yet few in De Lancey’s native country know the remarkable story of his transformation from American exile to British hero.

Born in New York City in 1778, De Lancey was a member of one of the city’s most powerful families, a clan whose roots reached back to the late 1600s. “The De Lancey name would have been at the apex of the social and political pecking order,” says Barnet Schecter, author of The Battle For New York: The City at the Heart of the American Revolution.

During the Revolution, the family name also became synonymous with Loyalism. William was named after the British general who had defeated George Washington in the Battle of Brooklyn in 1776. His grandfather Oliver De Lancey organized and funded three battalions of Loyalist fighters. When William was a toddler, he was at his grandfather’s estate (located amid what was then Manhattan farmland) when American raiders attacked and burned it to the ground.

That raid missed Oliver, who was not at home at the time, but no doubt terrorized his family, and it was a portent of things to come. In 1783, five-year-old William and his family evacuated New York, along with about 30,000 other Loyalists.

Unlike many of them, the De Lanceys had money and connections abroad. After a brief stay in Canada, William’s father, Stephen, moved the family to Beverley in Yorkshire, England, a Loyalist enclave. According to family genealogist Josepha De Lancey Altersitz, Stephen De Lancey secured an appointment as governor of the Bahamas in 1798, followed by a similar position in Tobago. His son remained in England and, at age 15, joined the army—often a last resort for young men without title or land, suggesting that despite the family’s wealth, young De Lancey still felt a need to prove himself in English society.

Whatever his motivations, he thrived. He rose through the ranks as a junior officer, serving in assignments from India to Ireland, and attended the new Royal Military College. In 1809, he joined Wellington’s staff for the Peninsular War against Napoleon. For his service during those six years of campaigning in Spain and Portugal, De Lancey earned a knighthood and the duke’s confidence.

“He was the ideal staff officer,” says David Crane, author of the acclaimed new book Went the Day Well?: Witnessing Waterloo. “Clever, confident in his own abilities, brave, decisive, trusted, meticulous, a good organizer and...less usual for a staff officer... greatly liked.”

Especially by Wellington. As Europe was enveloped in crisis after Napoleon’s escape from exile in March 1815, he demanded that De Lancey be re-assigned to his staff. At the time, the younger officer had been stationed in Scotland, where he had met Magdalene Hall, daughter of an eccentric scientist and scholar named Sir James Hall. The couple had been married only 10 days when De Lancey got the summons to join Wellington in Brussels. He arrived in late May, and his bride soon followed.

Napoleon had gathered an army, and a battle was imminent. Working with Wellington, De Lancey played a key role in its planning and execution. “De Lancey was what in modern terms would be defined as chief-of-staff,” says historian David Miller, author of Lady De Lancey at Waterloo: A Story of Duty and Devotion. “Wellington was undoubtedly responsible for strategy and the overall plan, but De Lancey was responsible for getting things done, moving the troops, allocating areas and responsibilities, and so on.”

This was no small task: Gregory Fremont-Barnes, a senior lecturer at the Royal Military Academy, notes that the British force at Waterloo numbered 73,000—about 10,000 fewer than the entire British Army today. De Lancey “had a daunting responsibility,” Fremont-Barnes says.

But the British were ready when the French cannon began firing late on the morning of June 18. There was fierce fighting over a two-and-a-half-mile front. In mid-afternoon, as de Lancey sat on horseback near the front lines with Wellington and a clutch of other officers, a ricocheting cannonball struck his shoulder. As Wellington later described it, the force “sent him many yards over the head of his horse. He fell on his face and bounded upwards and fell again. All the staff dismounted and ran to him, and when I came up he said, ‘Pray, tell them to leave me and let me die in peace.’ ”

Wellington had him carried to a makeshift field hospital.

Aided by the timely arrival of their Prussian allies, the British defeated the French that day, effectively ending a two-decade struggle with Napoleon and France. Wellington was the great hero of the battle. For De Lancey, what followed was a slow death from his wounds, made perhaps more bearable by the presence of Magdalene, who helped nurse him for a week at the dilapidated cottage that served as a hospital. She wrote a first-person account of their final days together that circulated among England’s literary elite; Charles Dickens wrote that he never read anything “so real, so touching.” Nearly a century later, in 1906, the memoir was published as a book, A Week at Waterloo in 1815, and became a best-seller.

Col. De Lancey’s death, however, was more than a Romantic Age tear-jerker. “Even if you can dispel the romantic glow that her story casts over his memory,” says Crane, “there is every evidence in the diaries, journals and recollections of the time, from Wellington himself downwards, that he was as grievously mourned as a man as he was as a soldier.”

What’s not clear is whether the American still identified with his native land in any shape or form, or whether he was self-conscious of his pedigree. His family knew from the American Revolution what it meant to be treated as second-class soldiers. “While people like Oliver De Lancey formed regiments of Loyalists, there was always this sting of the British not treating them as military equals,” Schecter says. “And look what happens to his grandson. They still call him ‘the American.’ It may have been affectionate, but it may also have been a bit of the same prejudice that’s been carried over.”

British historians argue that De Lancey’s roots would have been irrelevant in the more professional British army of the early 19th century, particularly to the commander in chief. “Wellington did not suffer fools or incompetents gladly,” Miller notes. “So the fact that De Lancey lasted for such a long time is in itself an indication of his abilities.”

Of course, we will never know what drove De Lancey, or what he felt toward the country of his birth. But there is no doubt that the American remains a hero of one of Britain’s finest hours.