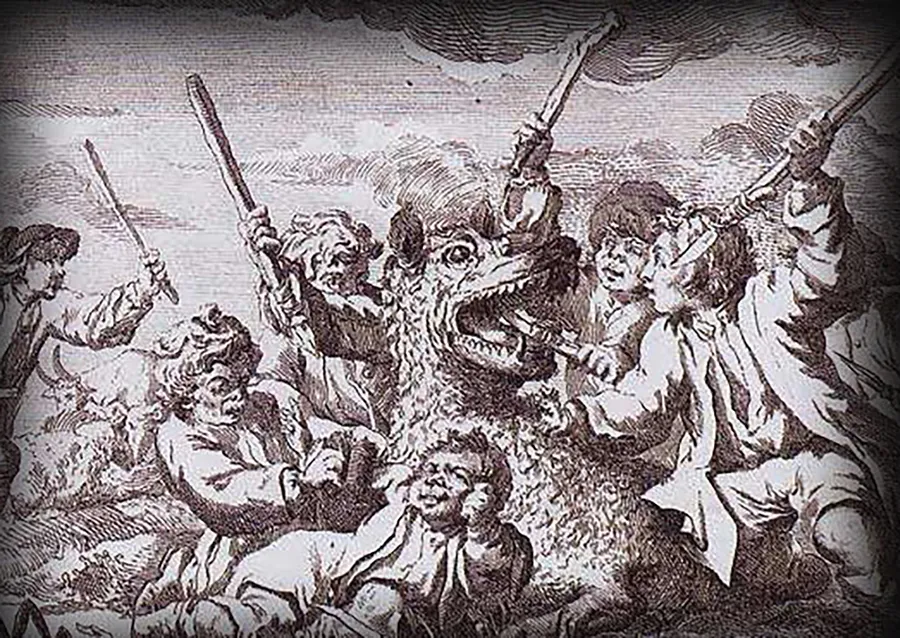

When the Beast of Gévaudan Terrorized France

The tale of this monster grew in the telling, but the carnage still left nearly 100 dead

:focal(689x260:690x261)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/77/f2/77f2ba47-23a8-4712-b6b4-aef2c683a505/dessin_de_la_bete_du_gevaudan_1765_-_archives_departementales_de_lherault_-_frad034-c440002-00001.jpg)

The monster’s first victim was Jeanne Boulet, a 14-year-old girl watching her sheep. Her death was followed by others, almost exclusively women and children. Throughout 1764, the brutal attacks—victims with their throats torn out or heads gnawed off—riveted France. The violence was so shocking, news of it traveled from the countryside all the way to the royal palace in Versailles. What was this beast of Gévaudan, and who could stop its reign of terror?

Gévaudan, a region in southern France (in modern-day Lozère), was just as mysterious as its monster. “It had the reputation for being a remote, isolated backwater where the forces of nature had not been full tamed, where the forests were indeed enchanted,” says Jay M. Smith, a historian and the author of Monsters of the Gévaudan: The Making of a Beast. “It’s fascinating, it’s powerful, it’s scary, it’s sublime.”

It was the perfect place for a Grimm-like fairy tale starring a possibly supernatural creature. But for villagers under attack, reality was more brutal than any book. In three years time, the beast racked up nearly 300 victims, and its legacy lasted long beyond the 18th century.

###

France of 1764 was in miserable condition. The Seven Years’ War had ended a year earlier, with France suffering numerous defeats at the hands of the British and the Prussians. The king, Louis XV, had also lost the bulk of his country’s overseas empire, including Canada. The economic situation was dire and the country was in disarray. Despite the carnage the beast wrought, it served as a perfect foe for a nation with something to prove, a country in need of a cause to rally around.

The beast and its victims might have gone virtually unnoticed if not for a burgeoning press. Because political news was mostly censored by the king, newspapers had to turn to other sources of information—and entertainment—to bolster subscriptions. François Morénas, creator and editor of the Courrier d’Avignon, used a new type of reporting called faits divers—stories of everyday incidents in small villages similar to today’s true crime—to tell the tale. His reportage in particular transformed the beast from a backwater calamity into a national affair.

As the headcount rose in 1764, local officials and aristocrats took action. Étienne Lafont, a regional government delegate, and Captain Jean Baptiste Duhamel, a leader of the local infantry, organize the first concerted attack. At one point, the number of volunteers rose to 30,000 men. Duhamel organized the men along military models, left poisoned bait, and even had some soldiers dress as peasant women in hopes of attracting the beast. A reward for killing the beast eventually equaled a year’s salary for workingmen, writes historian Jean-Marc Moriceau in La Bête du Gévaudan.

For men like Duhamel, the hunt was a way to redeem his honor after the war. “There are many signs of wounded masculinity among the lead huntsmen,” Smith says, especially Duhamel. “He had a highly sensitive regard for his own honor and had some bad experiences in the war, and looked at this challenge of defeating the beast as a way to redeem himself.”

The press also created popular stories out of the women and children who survived attacks by defending themselves, emphasizing the virtue of the peasantry.

Take Jacques Portefaix. The young boy and a group of children were out in a meadow with a herd of cattle on January 12, 1765, when the beast attacked. Working together, they managed to scare it off with their pikes. Portefaix’s courage was so admired that Louis XV paid a reward to all the children, and had the boy educated at the king’s personal expense.

And then there’s Marie-Jeanne Vallet, who was attacked on August 11, 1765, and managed to defend herself and wound the beast, earning herself the title “Maiden of Gévaudan.” Today a statue stands in her honor in the village of Auvers in southern France.

###

Individuals may have had some success defending themselves, but official hunters had none. In February 1765, the d’Ennevals, a father-son hunter duo from Normandy, announced they would travel to Gévaudan to eliminate the beast. Jean-Charles, the father, boasted he’d already killed 1,200 wolves, relevant information assuming the predator was, in fact, a wolf. But no one was sure of that. “It is much bigger than a wolf,” wrote Lafont in an early report. “It has a snout somewhat like a calf’s and very long hair, which would seem to indicate a hyena.”

Duhamel described the animal as even more fantastical. In his words, it had a “breast as wide as a horse,” “a body as long as a leopard’s,” and fur that’s that was “red with a black stripe.” Duhamel concluded, “You will undoubtedly think, like I do, that this is a monster [hybrid], the father of which is a lion. What its mother was remains to be seen.”

Other witnesses claimed the beast had supernatural abilities. “It could walk on its hind feet and its hide could repel bullets and it had fire in its eyes and it came back from the dead more than once and had amazing leaping ability,” Smith says.

Whatever its origins or appearance, the hunters were determined to score their prize. But again and again, they failed. The d’Ennevals eventually gave up at which point the king sent his own gun-bearer and bodyguard, François Antoine. Along with his son and a detachment of men, Antoine traipsed around the forested countryside in search of the beast. At last, in September 1765, he shot and killed a large wolf. He had the body sent to the court at Versailles, received a reward from Louis XV, and accepted the villagers’ gratitude

Two brief months later the attacks recommenced.

For another 18 months, something continued to stalk the villagers of Gévaudan, with a reported 30 to 35 fatalities in that period. The king, believing the beast had already been slain, offered little aid.

With no assistance coming from outside the region, locals took matters into their own hands—an option that may have been wiser from the beginning, since the previous hunters were unfamiliar with the landscape and had trouble communicating with locals.

Local farmer Jean Chastel had been involved in a previous hunt, but was thrown in prison by Antoine for leading his men into a bog. But his past crimes turned to bygones when he managed, at last, to bring the creature down with a bullet on June 19, 1767.

The end of the savagery did little to answer the burning question: What was the beast? It’s been up for debate ever since. Historians and scientists have suggested it was an escaped lion, a prehistoric holdover, or even that Chastel himself trained an animal to attack people and deflect attention from other crimes. Smith thinks the answer is more mundane.

“The best and most likely explanation is Gévaudan had a serious wolf infestation,” Smith says. In other words, there may not have been one single beast of Gévaudan, but many large wolves attacking the isolated communities.

Wolf attacks occurred throughout France during this period. Moriceau estimates that wolf attacks caused as many as 9,000 fatalities across the country between the end of the 16th century and the beginning of the 19th. What made the attacks in Gévaudan memorable, even to today, were their violence and higher-than-average fatalities, as well as the press’s ability to turn them into a riveting national story. Even 250 years since the Beast of Gévaudan last stalked the forests and fields of southern France, its fairy-tale-like legacy looms large.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)