People love dead Jews. Living Jews, not so much.

This disturbing idea was suggested by an incident this past spring at the Anne Frank House, the blockbuster Amsterdam museum built out of Frank’s “Secret Annex,” or in Dutch, “Het Achterhuis [The House Behind],” a series of tiny hidden rooms where the teenage Jewish diarist lived with her family and four other persecuted Jews for over two years, before being captured by Nazis and deported to Auschwitz in 1944. Here’s how much people love dead Jews: Anne Frank’s diary, first published in Dutch in 1947 via her surviving father, Otto Frank, has been translated into 70 languages and has sold over 30 million copies worldwide, and the Anne Frank House now hosts well over a million visitors each year, with reserved tickets selling out months in advance. But when a young employee at the Anne Frank House in 2017 tried to wear his yarmulke to work, his employers told him to hide it under a baseball cap. The museum’s managing director told newspapers that a live Jew in a yarmulke might “interfere” with the museum’s “independent position.” The museum finally relented after deliberating for six months, which seems like a rather long time for the Anne Frank House to ponder whether it was a good idea to force a Jew into hiding.

One could call this a simple mistake, except that it echoed a similar incident the previous year, when visitors noticed a discrepancy in the museum’s audioguide displays. Each audioguide language was represented by a national flag—with the exception of Hebrew, which was represented only by the language’s name in its alphabet. The display was eventually corrected to include the Israeli flag.

These public relations mishaps, clumsy though they may have been, were not really mistakes, nor even the fault of the museum alone. On the contrary, the runaway success of Anne Frank’s diary depended on playing down her Jewish identity: At least two direct references to Hanukkah were edited out of the diary when it was originally published. Concealment was central to the psychological legacy of Anne Frank’s parents and grandparents, German Jews for whom the price of admission to Western society was assimilation, hiding what made them different by accommodating and ingratiating themselves to the culture that had ultimately sought to destroy them. That price lies at the heart of Anne Frank’s endless appeal. After all, Anne Frank had to hide her identity so much that she was forced to spend two years in a closet rather than breathe in public. And that closet, hiding place for a dead Jewish girl, is what millions of visitors want to see.

* * *

Surely there is nothing left to say about Anne Frank, except that there is everything left to say about her: all the books she never lived to write. For she was unquestionably a talented writer, possessed of both the ability and the commitment that real literature requires. Quite the opposite of how an influential Dutch historian described her work in the article that spurred her diary’s publication—a “diary by a child, this de profundis stammered out in a child’s voice”—Frank’s diary was not the work of a naif, but rather of a writer already planning future publication. Frank had begun the diary casually, but later sensed its potential; upon hearing a radio broadcast in March of 1944 calling on Dutch civilians to preserve diaries and other personal wartime documents, she immediately began to revise two years of previous entries, with a title (Het Achterhuis, or The House Behind) already in mind, along with pseudonyms for the hiding place’s residents. Nor were her revisions simple corrections or substitutions. They were thoughtful edits designed to draw the reader in, intentional and sophisticated. Her first entry in the original diary, for instance, begins with a long description of her birthday gifts (the blank diary being one of them), an entirely unself-conscious record by a 13-year-old girl. The first entry in her revised version, on the other hand, begins with a deeply self-aware and ironic pose: “It’s an odd idea for someone like me to keep a diary; not only because I have never done so before, but because it seems to me that neither I—nor for that matter anyone else—will be interested in the unbosomings of a 13-year-old schoolgirl.”

The innocence here is all affect, carefully achieved. Imagine writing this as your second draft, with a clear vision of a published manuscript, and you have placed yourself not in the mind of a “stammering” child, but in the mind of someone already thinking like a writer. In addition to the diary, Frank also worked hard on her stories, or as she proudly put it, “my pen-children are piling up.” Some of these were scenes from her life in hiding, but others were entirely invented: stories of a poor girl with six siblings, or a dead grandmother protecting her orphaned grandchild, or a novel-in-progress about star-crossed lovers featuring multiple marriages, depression, a suicide and prophetic dreams. (Already wary of a writer’s pitfalls, she insisted the story “isn’t sentimental nonsense for it’s modeled on the story of Daddy’s life.”) “I am the best and sharpest critic of my own work,” she wrote a few months before her arrest. “I know myself what is and what is not well written.”

What is and what is not well written: It is likely that Frank’s opinions on the subject would have evolved if she had had the opportunity to age. Reading the diary as an adult, one sees the limitations of a teenager’s perspective, and longs for more. In one entry, Frank describes how her father’s business partners—now her family’s protectors—hold a critical corporate meeting in the office below the family’s hiding place. Her father, she and her sister discover that they can hear what is said by lying down with their ears pressed to the floor. In Frank’s telling, the episode is a comic one; she gets so bored that she falls asleep. But adult readers cannot help but ache for her father, a man who clawed his way out of bankruptcy to build a business now stolen from him, reduced to lying face-down on the floor just to overhear what his subordinates might do with his life’s work. When Anne Frank complains about her insufferable middle-aged roommate Fritz Pfeffer (Albert Dussel, per Frank’s pseudonym) taking his time on the toilet, adult readers might empathize with him as the only single adult in the group, permanently separated from his non-Jewish life partner whom he could not marry due to anti-Semitic laws. Readers Frank’s age connect with her budding romance with fellow hidden resident Peter van Pels (renamed Peter van Daan), but adults might wonder how either of the married couples in the hiding place managed their own relationships in confinement with their children. Readers Frank’s age relate to her constant complaints about grown-ups and their pettiness, but adult readers are equipped to appreciate the psychological devastation of Frank’s older subjects, how they endured not only their physical deprivation, but the greater blow of being reduced to a childlike dependence on the whims of others.

Frank herself sensed the limits of the adults around her, writing critically of her own mother’s and Peter’s mother’s apparently trivial preoccupations—and in fact these women’s prewar lives as housewives were a chief driver for Frank’s ambitions. “I can’t imagine that I would have to lead the same sort of life as Mummy and Mrs. v.P. [van Pels] and all the women who do their work and are then forgotten,” she wrote as she planned her future career. “I must have something besides a husband and children, something that I can devote myself to!” In the published diary, this passage is immediately followed by the famous words, “I want to go on living even after my death!”

By plastering this sentence on Frank’s book jackets, publishers have implied that her posthumous fame represented the fulfillment of the writer’s dream. But when we consider the writer’s actual ambitions, it is obvious that her dreams were in fact destroyed—and it is equally obvious that the writer who would have emerged from Frank’s experience would not be anything like the writer Frank herself originally planned to become. Consider, if you will, the following imaginary obituary of a life unlived:

Anne Frank, noted Dutch novelist and essayist, died Wednesday at her home in Amsterdam. She was 89.

A survivor of Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen, Frank achieved a measure of fame that was hard won. In her 20s she struggled to find a publisher for her first book, "The House Behind." The two-part memoir consisted of a short first section detailing her family’s life in hiding in Amsterdam, followed by a much longer and more gripping account of her experiences at Auschwitz, where her mother and others who had hidden with her family were murdered, and later at Bergen-Belsen, where she witnessed her sister Margot’s horrific death.

Disfigured by a brutal beating, Frank rarely granted interviews; her later work, "The Return," describes how her father did not recognize her upon their reunion in 1945. "The House Behind" was searing and accusatory: The family’s initial hiding place, mundane and literal in the first section, is revealed in the second part to be a metaphor for European civilization, whose facade of high culture concealed a demonic evil. “Every flat, every house, every office building in every city,” she wrote, “they all have a House Behind.” The book drew respectful reviews, but sold few copies.

She supported herself as a journalist, and in 1961 traveled to Israel to cover the trial of Adolf Eichmann for the Dutch press. She earned special notoriety for her fierce reporting on the Nazi henchman’s capture, an extradition via kidnapping that the Argentine elite condemned.

Frank soon found the traction to publish Margot, a novel that imagined her sister living the life she once dreamed of, as a midwife in the Galilee. A surreal work that breaks the boundaries between novel and memoir, and leaves ambiguous which of its characters are dead or alive, Margot became wildly popular in Israel. Its English translation allowed Frank to find a small but appreciative audience in the United States.

Frank’s subsequent books and essays continued to win praise, if not popularity, earning her a reputation as a clear-eyed prophet carefully attuned to hypocrisy. Her readers will long remember the words she wrote in her diary at 15, included in the otherwise naive first section of "The House Behind": “I don’t believe that the big men are guilty of the war, oh no, the little man is just as guilty, otherwise the peoples of the world would have risen in revolt long ago! There’s in people simply an urge to destroy, an urge to kill, to murder and rage, and until all mankind without exception undergoes a great change, wars will be waged, everything that has been built up, cultivated and grown will be cut down and disfigured, and mankind will have to begin all over again.”

Her last book, a memoir, was titled "To Begin Again."

* * *

The problem with this hypothetical, or any other hypothetical about Frank’s nonexistent adulthood, isn’t just the impossibility of knowing how her life and career might have developed. The problem is that the entire appeal of Anne Frank to the wider world—as opposed to those who knew and loved her—lies in her lack of a future.

There is an exculpatory ease to embracing this “young girl,” whose murder is almost as convenient for her many enthusiastic readers as it was for her persecutors, who found unarmed Jewish children easier to kill off than the Allied infantry. After all, an Anne Frank who lived might have been a bit upset at the Dutch people who, according to the leading theory, turned in her household and received a reward of approximately $1.40 per Jew. An Anne Frank who lived might not have wanted to represent “the children of the world,” particularly since so much of her diary is preoccupied with a desperate plea to be taken seriously—to not be perceived as a child. Most of all, an Anne Frank who lived might have told people about what she saw at Westerbork, Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen, and people might not have liked what she had to say.

And here is the most devastating fact of Frank’s posthumous success, which leaves her real experience forever hidden: We know what she would have said, because other people have said it, and we don’t want to hear it.

The line most often quoted from Frank’s diary—“In spite of everything, I still believe that people are really good at heart”—is often called “inspiring,” by which we mean that it flatters us. It makes us feel forgiven for those lapses of our civilization that allow for piles of murdered girls—and if those words came from a murdered girl, well, then, we must be absolved, because they must be true. That gift of grace and absolution from a murdered Jew (exactly the gift, it is worth noting, at the heart of Christianity) is what millions of people are so eager to find in Frank’s hiding place, in her writings, in her “legacy.” It is far more gratifying to believe that an innocent dead girl has offered us grace than to recognize the obvious: Frank wrote about people being “truly good at heart” three weeks before she met people who weren’t.

Here’s how much some people dislike living Jews: They murdered six million of them. Anne Frank’s writings do not describe this process. Readers know that the author was a victim of genocide, but that does not mean they are reading a work about genocide. If that were her subject, it is unlikely that those writings would have been universally embraced.

We know this because there is no shortage of texts from victims and survivors who chronicled the fact in vivid detail, and none of those documents has achieved anything like the fame of Frank’s diary. Those that have come close have only done so by observing the same rules of hiding, the ones that insist on polite victims who don’t insult their persecutors. The work that came closest to achieving Frank’s international fame might be Elie Wiesel’s Night, a memoir that could be thought of as a continuation of Frank’s experience, recounting the tortures of a 15-year-old imprisoned in Auschwitz. As the scholar Naomi Seidman has discussed, Wiesel first published his memoir in Yiddish, under the title And the World Kept Silent. The Yiddish book told the same story, but it exploded with rage against his family’s murderers and, as the title implies, the entire world whose indifference (or active hatred) made those murders possible. With the help of the French Catholic Nobel laureate François Mauriac, Wiesel later published a French version of the book under the title Night—a work that repositioned the young survivor’s rage into theological angst. After all, what reader would want to hear about how his society had failed, how he was guilty? Better to blame God. This approach did earn Wiesel a Nobel Peace Prize, as well as a spot in Oprah’s Book Club, the American epitome of grace. It did not, however, make teenage girls read his book in Japan, the way they read Frank’s. For that he would have had to hide much, much more.

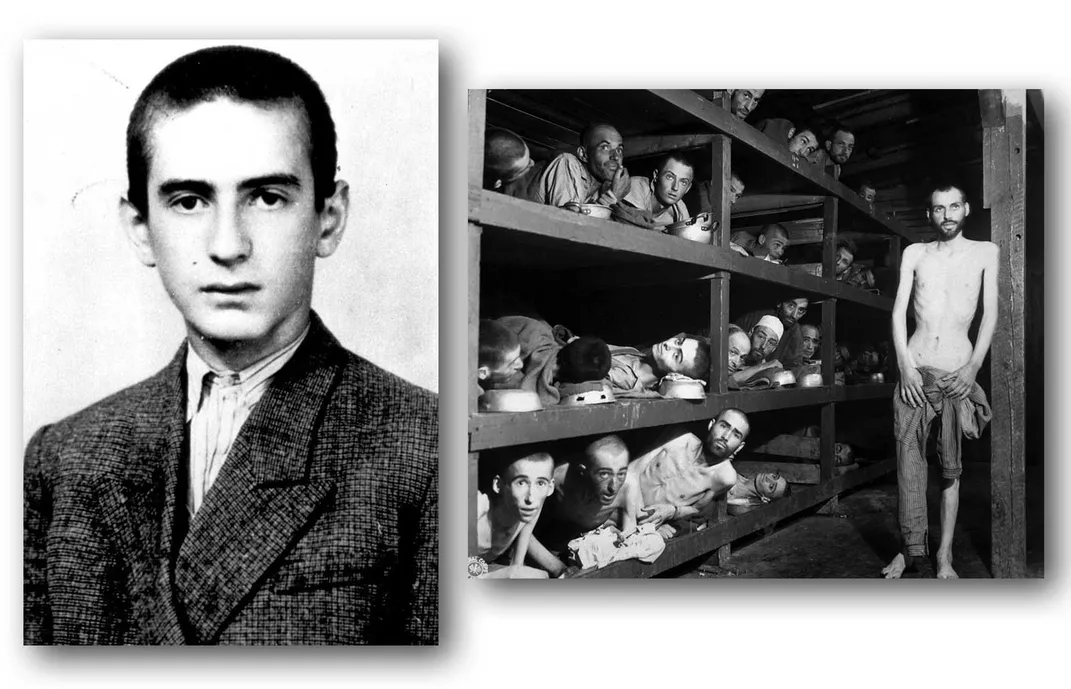

What would it mean for a writer not to hide the horror? There is no mystery here, only a lack of interest. To understand what we are missing, consider the work of another young murdered Jewish chronicler of the same moment, Zalmen Gradowski. Like Frank’s, Gradowski’s work was written under duress and discovered only after his death—except that Gradowski’s work was written in Auschwitz, and you have probably never heard of it.

Gradowski was one of the Jewish prisoners in Auschwitz’s Sonderkommando: those forced to escort new arrivals into the gas chambers, haul the newly dead bodies to the crematoriums, extract any gold teeth and then burn the corpses. Gradowski, a young married man whose entire family was murdered, reportedly maintained his religious faith, reciting the kaddish (mourner’s prayer) each evening for the victims of each transport—including Peter van Pels’ father, who was gassed a few weeks after his arrival in Auschwitz on September 6, 1944. Gradowski recorded his experiences in Yiddish in documents he buried, which were discovered after the war; he himself was killed on October 7, 1944, in a Sonderkommando revolt that lasted only one day. (The documents written by Gradowski and several other prisoners inspired the 2015 Hungarian film Son of Saul, which, unsurprisingly, was no blockbuster, despite an Academy Award and critical acclaim.)

“I don’t want to have lived for nothing like most people,” Frank wrote in her diary. “I want to be useful or give pleasure to the people around me who don’t yet know me, I want to go on living even after my death!” Gradowski, too, wrote with a purpose. But Gradowski’s goal wasn’t personal or public fulfillment. His was truth: searing, blinding prophecy, Jeremiah lamenting a world aflame.

“It may be that these, the lines that I am now writing, will be the sole witness to what was my life,” Gradowski writes. “But I shall be happy if only my writings should reach you, citizen of the free world. Perhaps a spark of my inner fire will ignite in you, and even should you sense only part of what we lived for, you will be compelled to avenge us—avenge our deaths! Dear discoverer of these writings! I have a request of you: This is the real reason why I write, that my doomed life may attain some meaning, that my hellish days and hopeless tomorrows may find a purpose in the future.” And then Gradowski tells us what he has seen.

Gradowski’s chronicle walks us, step by devastating step, through the murders of 5,000 people, a single large “transport” of Czech Jews who were slaughtered on the night of March 8, 1944—a group that was unusual only because they had already been detained in Birkenau for months, and therefore knew what was coming. Gradowski tells us how he escorted the thousands of women and young children into the disrobing room, marveling at how “these same women who now pulsed with life would lie in dirt and filth, their pure bodies smeared with human excrement.” He describes how the mothers kiss their children’s limbs, how sisters clutch each other, how one woman asks him, “Say, brother, how long does it take to die? Is it easy or hard?” Once the women are naked, Gradowski and his fellow prisoners escort them through a gantlet of SS officers who had gathered for this special occasion—a night gassing arranged intentionally on the eve of Purim, the biblical festival celebrating the Jews’ narrow escape from a planned genocide. He recalls how one woman, “a lovely blond girl,” stopped in her death march to address the officers: “‘Wretched murderers! You look at me with your thirsty, bestial eyes. You glut yourselves on my nakedness. Yes, this is what you’ve been waiting for. In your civilian lives you could never even have dreamed about it. [...] But you won’t enjoy this for long. Your game’s almost over, you can’t kill all the Jews. And you will pay for it all.’ And suddenly she leaped at them and struck Oberscharführer Voss, the director of the crematoriums, three times. Clubs came down on her head and shoulders. She entered the bunker with her head covered with wounds [...] she laughed for joy and proceeded calmly to her death.” Gradowski describes how people sang in the gas chambers, songs that included Hatikvah, “The Hope,” now the national anthem of Israel. And then he describes the mountain of open-eyed naked bodies that he and his fellow prisoners must pull apart and burn: “Their gazes were fixed, their bodies motionless. In the deadened, stagnant stillness there was only a hushed, barely audible noise—a sound of fluid seeping from the different orifices of the dead. [...] Frequently one recognizes an acquaintance.” In the specially constructed ovens, he tells us, the hair is first to catch fire, but “the head takes the longest to burn; two little blue flames flicker from the eyeholes—these are the eyes burning with the brain. [...] The entire process lasts 20 minutes—and a human being, a world, has been turned to ashes. [...] It won’t be long before the five thousand people, the five thousand worlds, will have been devoured by the flames.”

Gradowski was not poetic; he was prophetic. He did not gaze into this inferno and ask why. He knew. Aware of both the long recurring arc of destruction in Jewish history, and of the universal fact of cruelty’s origins in feelings of worthlessness, he writes: “This fire was ignited long ago by the barbarians and murderers of the world, who had hoped to drive darkness from their brutal lives with its light.”

One can only hope that we have the courage to hear this truth without hiding it, to face the fire and to begin again.

:focal(3278x642:3279x643)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/02/c2/02c28d97-a2f5-433b-a969-afa326a2cfd3/nov2018_e03_annefrankessay_se.jpg)