Before Salem, There Was the Not-So-Wicked Witch of the Hamptons

Why was Goody Garlick, accused of witchcraft in 1658, spared the fate that would befall the women of Massachusetts decades later

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Hampton-Witches-windmill-631.jpg)

Thirty-five years before the infamous events of Salem, allegations of witchcraft and a subsequent trial rocked a small colonial village.

The place was Easthampton, New York. Now a summer resort for the rich and famous—and spelled as two words, East Hampton—at the time it was an English settlement on the remote, eastern tip of Long Island.

There, in February, 1658, 16-year old Elizabeth Gardiner Howell, who had recently given birth to a child, fell ill. As friends ministered to her, she terrified them by suddenly shrieking: "A witch! A witch! Now you are come to torture me because I spoke two or three words against you!” Her father, Lion Gardiner, a former military officer and the town’s most prominent citizen, was summoned. He found his daughter at the foot of her bed, screaming that the witch was in the room. "What do you see?" he asked her.

"A black thing at the bed's feet," she answered, flailing at an invisible adversary.

A day later, Howell died—after having fingered her tormentor as one Elizabeth Garlick, a local resident who often quarreled with neighbors.

A board of inquiry was formed, composed of three male magistrates. They listened to testimony from many of the town’s citizens, some of whom had known “Goody” Garlick since their days in Lynn, Massachusetts, where a number of Easthampton’s residents had lived before re-settling here (In Puritan society, the honorific Goody, short for Goodwife, was given to most women of what we would now call working class status).

The Easthampton town records—which still exist, and allow us to know many of the details of this case—catalog a litany of accusations of supernatural behavior by Garlick. She supposedly cast evil eyes and sent animal familiars out to do her bidding. Someone claimed that she picked up a baby and after putting it down, the child took sick and died. She was blamed for illnesses, disappearances, the injuries and death of livestock.

“These were people on edge,” says Hugh King, a local East Hampton historian, who along with his wife, anthropologist Loretta Orion, have researched and written extensively about the Garlick case. “If you look at the court records before this started, people were constantly suing and arguing with each other about all kinds of things we might see as trivial today.”

Garlick was a particularly good target. “She was probably a rather obstreperous person to begin with,” King guesses. “Or maybe it was jealousy.”

Jealousy of Garlick’s husband, perhaps? Joshua Garlick had worked on Lion Gardiner’s island estate—a plum job. He is mentioned in some of Gardiner’s surviving correspondence, and seems to have been a rather trusted employee. Gardiner once trusted Garlick with carrying large sums of his money to make a purchase.

The East Hampton magistrates, having collected the testimony, decided to refer the case to a higher court in Hartford. (As historian Bob Hefner explained in his The History of East Hampton, the village adopted the laws of Connecticut Colony in 1653 and officially became part of the colony four years later. It joined New York Colony in 1664 but kept a commercial and cultural allegiance to New England for centuries more.)

The magistrate’s deference to Hartford alone, the historian T.H. Breen believes, was in some senses an admission of failure. “A little village had proven unable to control the petty animosities among its inhabitants,” he wrote in his 1989 history of East Hampton, Imagining the Past (Addison Wesley). “By 1658, the vitriol had escalated to the point where the justices were forced to seek external assistance.”

Still, the charges against Garlick went well beyond the “your-cow-broke-my-fence” accusations. Witchcraft was a capitol offense—and Connecticut had a record of knowing exactly what do with convicted witches; they had executed several unfortunate women them in the previous years.

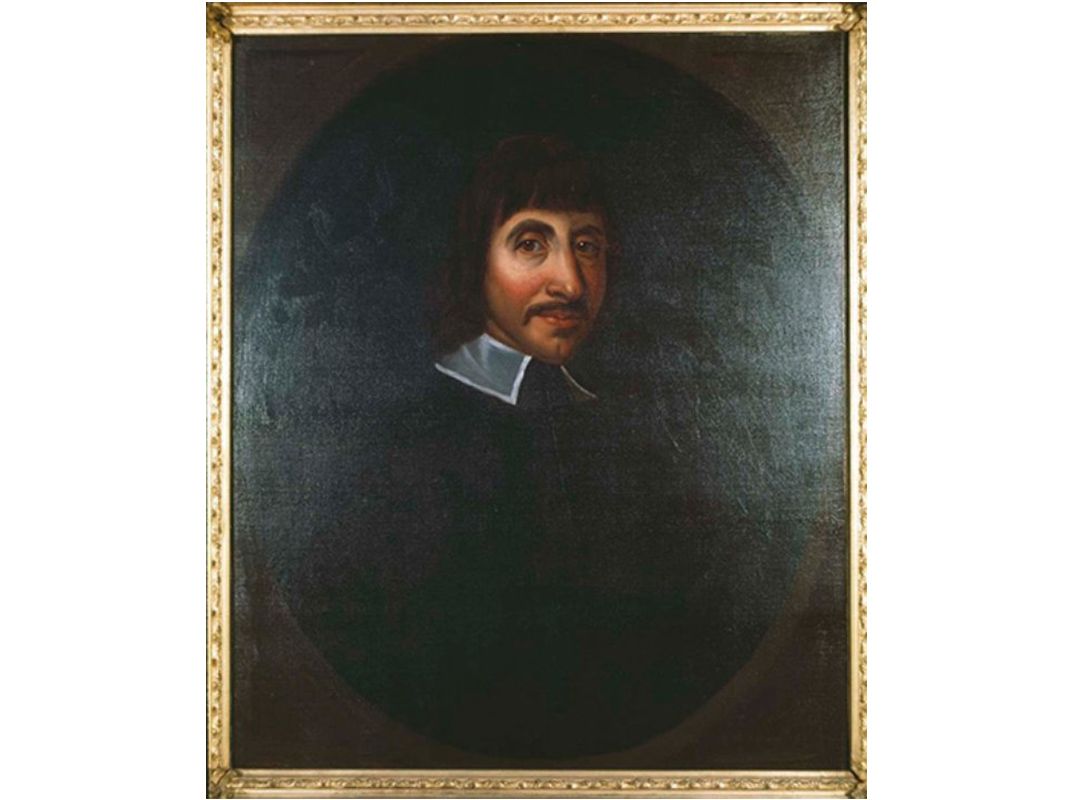

But there was a new sheriff in town in 1658: John Winthrop, Jr.—son of the co-founder of the Massachusetts Bay Colony—had recently been persuaded to take the position of Governor of the Hartford colony. This was a stroke of good luck for Garlick.

Although it might be too much to suggest that Winthrop, Jr. was an Enlightenment Man a century before the Enlightenment, he was certainly a more forward thinker than many of his contemporaries. “Virtually every person alive in the 17th century believed in the power of magic,” says Connecticut state historian Walter Woodward, an associate professor at the University of Connecticut. “But some people were far more skeptical about the role of the devil in magic, and about the ability of common people to practice magic.”

Junior was one of those skeptics.

In part, this was because he was a scholar, a healer, and, although he would not have recognized the term, a scientist. His research sought to explain the magical forces in nature that he and most learned men of his day felt were responsible for the world around them. “He spent his life seeking mastery over the hidden forces at work in the cosmos,” says Woodward, who is also the author of Prospero's America: John Winthrop, Jr., Alchemy and the Creation of New England Culture, 1606-1675 (University of North Carolina Press, 2010).

Winthrop was dubious that your average farmer’s wife—or for that matter, anyone without his level of training or experience—could perform the kinds of magical acts attributed to witches. So he looked to another explanation for people like Goody Garlick and their alleged crimes; one that would likely put him in concert with sociologists and historians today.

“He saw witchcraft cases as an incidence of community pathology,” Woodward says. “The pattern is clear in cases in which he is involved. It’s the pattern of not finding the witches quite guilty, but putting pressure on them to better conform to social norms. At the same time, he acknowledges the justification of the community to be concerned about witchcraft, but he never empowers the community to follow through on that.”

That pattern was established in the Garlick case, the first of several involving witches that Winthrop, Jr. would oversee over the next decade.

No doubt after consulting with Gardiner—a long time associate with whom he had established the settlement of Saybrook, during the Pequot Wars—Winthrop’s court rendered a not-guilty verdict. While the records of the trial do not exist, the court’s nuanced directive to the citizens of East Hampton does. It didn’t quite dismiss the idea that Goody Garlick might have been up to something fishy; nor did it come out and label the townspeople who had paraded their second and third hand allegations against her a bunch of busybodies. But the court made perfectly clear what they expected from both the Garlicks and the community of Easthampton:

“It is desired and expected by this court that you should carry neighborly and peaceably without just offense, to Jos. Garlick and his wife, and that they should do the like to you.”

Apparently, that’s exactly what happened. As far as can be told from the East Hampton town records, the Garlicks resumed their lives in the community. Chances are they weren’t invited to too many parties, but King notes that their son later became the miller of the town—a fairly prominent position.

Asked how Winthrop’s decision on the Garlick case affected the community, King summed it up: “Did we have any more accusations of witchcraft in Easthampton after that? No. Did the town prosper and grow? Yes.”

Perhaps it’s no surprise, then, that today East Hampton is known for its night clubs, beaches and celebrity sightings, while the name Salem, Massachusetts--where 19 people were hung in 1693—will forever be associated with the horrors of a witch hunt unleashed.

On Friday, November 9, the East Hampton Historical Society will hold a walking tour and re-enactment of the Garlick case. The tour, which starts 5 p.m. at Clinton Academy, 151 Main Street in East Hampton is $15. For information call 631-324-6850.