Charles Atlas: Muscle Man

How the original 97-pound-weakling transformed himself and brought physical fitness to the masses

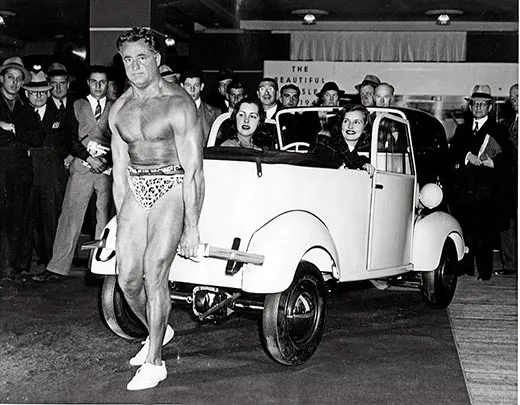

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Charles-Atlas-tug-of-war-Rockettes-631.jpg)

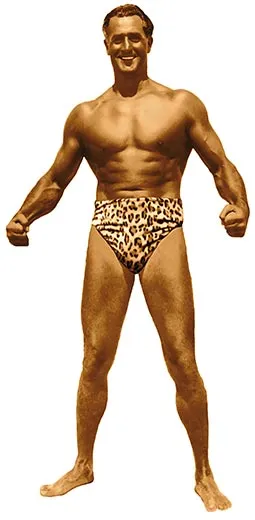

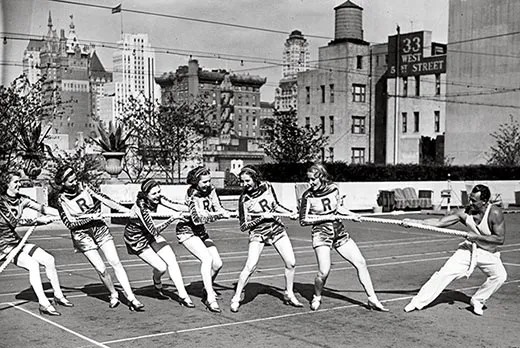

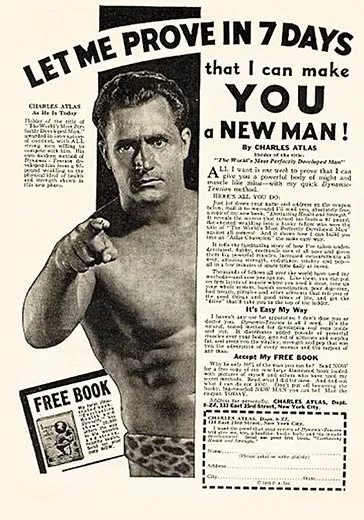

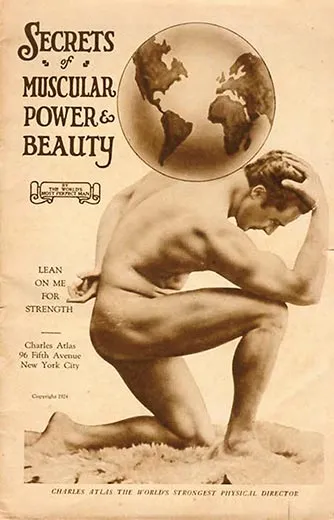

Like tens of thousands of young men and boys before him, Tom Manfre first caught sight of Charles Atlas in the back pages of the comic books he read so voraciously. With a sculpted chest, leopard briefs girdling his hips, a piercing look on his granite-jawed face, Atlas seemed to be jabbing his finger at Manfre as he commanded: "Let Me Prove in 7 Days That I Can Make You a New Man!"

It was 1947, Manfre was 23 years old, and the man in the leopard-pattern briefs was the toast of New York City. He'd helped President Franklin Roosevelt celebrate his birthday at the Waldorf Astoria hotel. He cavorted on radio with Fred Allen and Eddie Cantor and on television with Bob Hope and Garry Moore. He stripped off his shirt at a Paris dinner party tossed by the designer Elsa Schiaparelli. His measurements had been entombed in the famous Crypt of Civilization, the repository of records at Oglethorpe University in Atlanta intended for unsealing in the year 8113. Scarcely a day went by that a newspaper columnist didn't feature an item about Atlas—dropping by to bend a couple of railroad spikes, perhaps, or ripping a Manhattan phone book in half.

Manfre stuck a check for $29.95 in the mail and got back a 12-lesson course of exercises the author called Dynamic-Tension. For 90 days, Manfre did the prescribed squats and leg-raises and sit-ups. He followed the tips on sleep and nutrition. He remembered to chew his food slowly. Pleased with the results, he sent a photograph of his new and improved body to Atlas and was invited to drop by to meet the man himself.

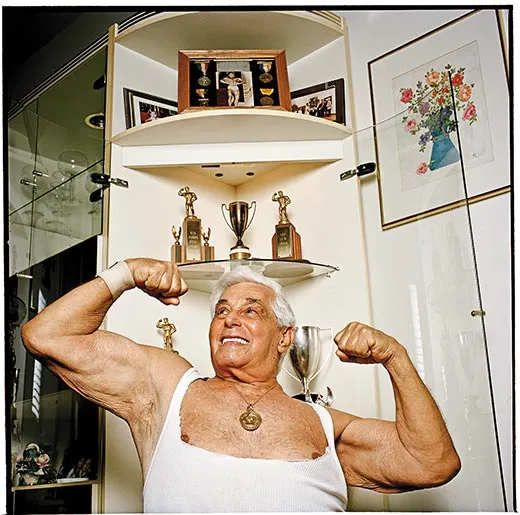

"I felt like a kid in a candy store," Manfre, 86, says today. "I was thrilled! He put an arm around me and said, ‘God was good to me, and I'm sure he'll be good to you.'" When Manfre won the Mr. World contest six years later, the first person he called to thank was Charles Atlas.

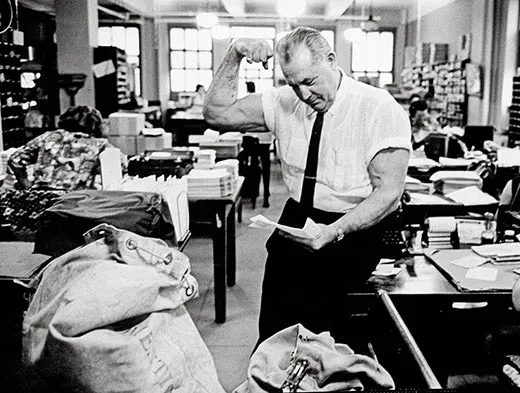

Manfre was not alone in his gratitude. During Atlas' heyday—the 1930s and '40s—two dozen women worked eight-hour days to open and file the letters that poured into his downtown Manhattan office. Grateful knock-kneed boys with scrawny arms and sunken chests reported that their lives had been turned around. King George VI of England signed up. Boxers and bodybuilders gave Dynamic-Tension a whirl. Mahatma Gandhi—Gandhi!—wrote to inquire about the course. A 1999 A&E biography, "Charles Atlas: Modern Day Hercules," included testimonials from Arnold Schwarzenegger and Jake "Body by Jake" Steinfeld.

This year marks the 80th that Atlas' mail-order company has been in business. Atlas himself is long gone—he died in 1972—and Charles Atlas Ltd. now operates out of a combined shrine, archive and office over a nail salon in the northern New Jersey town of Harrington Park. But the Internet has given Dynamic-Tension a new life. From all over the world, letters and e-mails continue to pour in, testament to one of the most successful fitness programs ever devised. And to its mythic founder.

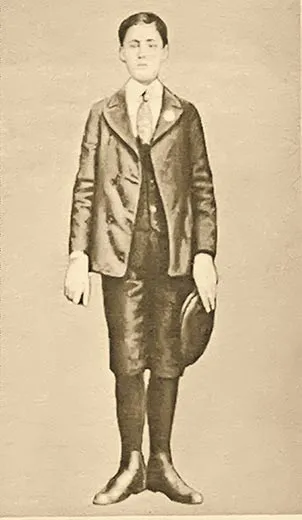

The man who made history marketing his muscles was an unlikely hero. Born in Acri, a tiny town in southern Italy, he arrived with his parents at Ellis Island in 1903 at age 10. His name was Angelo Siciliano, and he spoke not a word of English.

He didn't look like much, either. Skinny and slope-shouldered, feeble and often ill, he was picked on by bullies in the Brooklyn neighborhood where his family had settled, and his own uncle beat him for getting into fights. He found little refuge at Coney Island Beach, where a hunky lifeguard kicked sand in his face and a girlfriend sighed when the 97-pound Atlas swore revenge.

On a visit to the Brooklyn Museum, he saw statuary depicting Hercules, Apollo and Zeus. That, and Coney Island's sideshow, got him thinking. Bodybuilding was then a fringe pursuit, its practitioners consigned to the freak tents beside the fat lady and the sword swallower. Alone at the top was Eugen Sandow, a Prussian strongman discovered by showman Florenz Ziegfeld. Sandow toured vaudeville theaters, lifting ponies and popping chains with his chest. Atlas pasted a photo of Sandow on his dresser mirror and, hoping to transform his own body, spent months sweating away at home with a series of makeshift weights, ropes and elastic grips. The results were disappointing, but on a visit to the Bronx Zoo one day he had an epiphany, or so he would recall in his biography Yours in Perfect Manhood, by Charles Gaines and George Butler. Watching a lion stretch, he thought to himself, "Does this old gentleman have any barbells, any exercisers?...And it came over me....He's been pitting one muscle against another!"

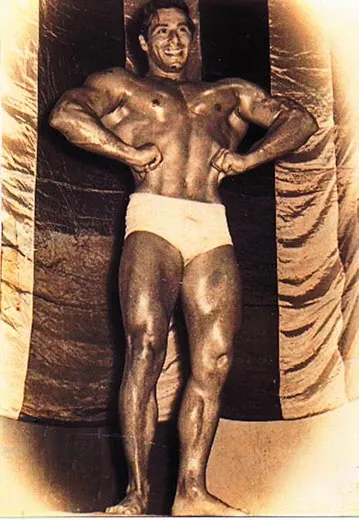

Atlas threw out his equipment. He began flexing his muscles, using isometric opposition and adding range of motion to stress them further. He tensed his hands behind his back. He laced his fingers under his thighs and pushed his hands against his legs. He did biceps curls with one arm and squeezed his fist down with the other. Experimenting with varied techniques, and likely aided by exceptional genes, Atlas emerged from many months at home with a physique that stunned school chums when he first revealed himself on the beach. One of the boys exclaimed, "You look like that statue of Atlas on top of the Atlas Hotel!"

Several years later, he legally changed his name, adding Charles from his nickname "Charlie."

Holding up the world, however, wasn't a career. Atlas was too mild-mannered to go chasing neighborhood bullies, though on the New York subway he once lifted a troublemaker by his lapels and issued him a stern warning. A dutiful son, he learned leatherworking to pay the rent and support his mother. (His father had taken one look at his adopted home and high-tailed it back to Italy.) But Charlie hadn't built up his chest just to make purses. Eventually, he gave up on the leatherwork and took a $5-a-week job, doubling as janitor and strongman at the Coney Island sideshow, where he lay on a bed of nails and urged men from the audience to stand on his stomach.

And this might have been the last anyone heard of Charles Atlas had an artist not spotted him on the beach in 1916 and asked him to pose.

A boom in public sculpture was coming, and busy carvers were desperate for models with well-built bodies. Among the most prominent was socialite sculptor Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, who, watching Atlas disrobe, exclaimed, "He's a knockout!" Further impressed by his ability to hold a pose for 30 minutes, she soon had him running from studio to studio. By the time he was 25, Atlas was everywhere, posing as George Washington in Washington Square Park, as Civic Virtue in Queens Borough Hall, as Alexander Hamilton in the nation's capital. He was Dawn of Glory in Brooklyn's Prospect Park and Patriotism for the Elks' national headquarters in Chicago. Photographs of him in classic poses, nude or shockingly close to it and with more than a whiff of eroticism, suggest how much he liked the camera and the camera liked him.

And the money was good—$100 a week. Still, Atlas was restless, and ambitious, and when he saw an ad for a "World's Most Beautiful Man" photo contest, he sent in his picture.

The contest was sponsored by Physical Culture magazine, the brainchild of Bernarr Macfadden, a publisher and fitness fanatic, as well as one of the most bizarre figures in the annals of fitness entrepreneurs. (He would later found a publishing empire with True Story and True Romances magazines.) Macfadden was obsessive about his health. When he wasn't fasting, he ate carrots, beans, nuts and raw eggs. He slept on the floor and walked to work barefoot. Impressed with Atlas' photograph, he asked the young man to stop by his office. When Atlas stripped to his leopard bikini, Macfadden stopped the contest, though he waited for a second visit to hand over the $1,000 winner's check and celebrate with a glass of carrot juice.

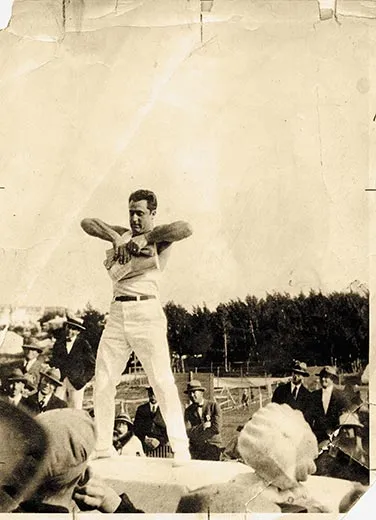

Atlas got an even bigger jolt of publicity when, in 1922, Macfadden followed up the contest with "The World's Most Perfectly Developed Man" extravaganza at Madison Square Garden. Seven hundred and seventy-five men competed for the title, judged by a panel of doctors and artists. When Atlas walked away with a second trophy, Macfadden called a halt to any more contests, grousing that Atlas would win every year. Likely, he was merely hyping Atlas' next showstopper: starring in a Macfadden short, silent movie called The Road to Health, directed by one Frederick Tilney, a busy if unsung health and fitness expert. On a ride to the film studios in Fort Lee, New Jersey, one day, Tilney and Atlas decided to set up a mail-order business to sell an exercise routine. When, after a few years, their collaboration ended, Atlas went solo.

But an extraordinary body did not translate into a head for business, and, within a few years, the company floundered. With profits lagging, Atlas' advertising agency in 1928 turned over his account to its newest hire, Charles Roman, who was 21 and fresh out of New York University. What the young man came up with so impressed Atlas that four months after they met, Atlas offered him half the company on the condition that Roman would run it. It was the smartest move he ever made.

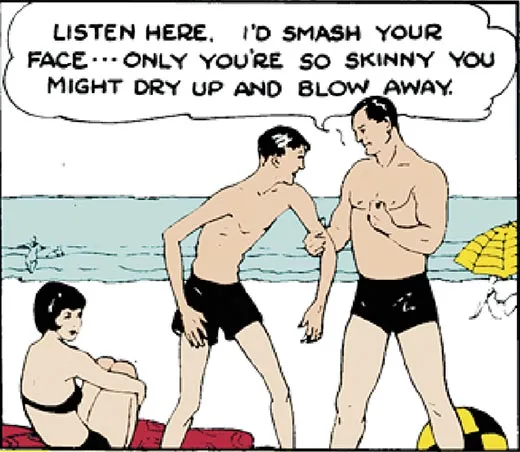

Roman knew a thing or two about writing ad copy and a lot about psychology, and he'd scarcely sharpened his pencils before he coined the term "Dynamic-Tension." He would do more than save the business; he would turn it into a marketing landmark. It was Roman who would write all the Atlas ads, from the "Hey, Skinny!" strips to the "97-Pound Weakling" and the "The Insult That Made a Man Out of ‘Mac'" series. The ads went straight to the male psyche. They preyed on every man's insecurity—that he wasn't "man enough" to defend his girl at the beach. At a time when the entire country was reeling from the 1929 stock-market crash and its aftermath, Atlas promised to restore a million battered egos.

"When the Depression struck, a characteristic response in America was to blame ourselves," says Harvey Green, a professor of history at Northeastern University and author of Fit for America: Health, Fitness, Sport and American Society, 1830-1940. "Atlas interpreted the desire to transform ourselves as a way of self-improvement."

The story of the two Charleses—Atlas and Roman— was a marriage of muscle and marketing that permanently altered America's approach to fitness. Before them, exercise had been the habit of a few, motivated by health first with vanity a distant second. Roman's ads heralded a new view of a man's body—as a measurement of success. As people migrated from rural America to cities filled with offices, making an impression became a priority. It was why Dale Carnegie, author of How to Win Friends and Influence People, had won so many readers. But where Carnegie preached advancement through social skills, Atlas evangelized for the body beautiful.

"Carnegie's message was, fit in—Atlas' was to be bigger than everybody else," says Green. "Then nobody would mess with you. The idea that physical size could give you confidence was a powerful message."

Brute size was all well and good, but proportions were what mattered to Atlas. "I don't stress the matter of chest expansion," he told Family Circle magazine in 1939, "because it is not important....I've had a fellow in here who could blow himself up like a frog...but it was just a trick, and he was underdeveloped in every way." Nor did big biceps impress Atlas as much as well-developed abs. In one of his lessons, he wrote, "It is all very well to have strong arms and a grip of steel, but of what use are these unless the abdominal area is in perfect condition?" The paragraph concludes: "The rectus abdomus muscles will stand out firmly like a washboard."

His values were curiously old-fashioned, even quaint. Manfre was always surprised by Atlas' interest in his life. "He'd constantly ask me questions. ‘What did you do yesterday? How's it going? Did you go to church? I've got a new exercise you should add in.'" That Atlas never stopped working to improve his exercise program also impressed Manfre. "He kept studying animals," says Manfre, "and not just four-legged ones. He'd say, ‘See that bird fly? See how he flaps his wings to push out his chest?' I'd sit there amazed."

The personal touch was his hallmark; his lessons took the form of letters signed by the man himself: "Yours for Health and Strength" or "Yours for Perfect Development" or "Yours in Perfect Manhood" or (during World War II) "Yours for a Lasting Peace." Long before personal trainers, Atlas tried to create an intimate bond with his "students." That the exercises could be performed alone at home, without risk of embarrassment at a YMCA or club, was part of their appeal. "You will understand these exercises better," Atlas empathized, "if you read them out loud to yourself in a private room where you will not be disturbed."

Of course, not everyone bought into Dynamic-Tension. Most notably, Atlas feuded with a man named Bob Hoffman, who published Strength & Health magazine and sold York barbells on the side. In a celebrated case filed with the Federal Trade Commission in 1936, Hoffman called the Atlas system "dynamic hooey" and stood on his thumbs before the commission to prove the value of barbells. The FTC was apparently impressed—but not persuaded. In its finding of fact, it declared that Atlas "has employed and developed his said system since he was seventeen years of age and has attained his own great strength by the use of his own methods without relying upon apparatus." The FTC dismissed the suit and issued an order warning Hoffman not to disparage Atlas again.

John D. Fair, author of the biography Muscletown USA: Bob Hoffman and the Manly Culture of York Barbell, says he found articles in old issues of Physical Culture in which Atlas admitted he supplemented his exercises by using weights. But Fair also gives credit to Atlas. "He was an awfully nice guy with a great body, handsome and very strong," he told me. "He was a look, a household name. Hoffman admired him, but Hoffman was a businessman."

Terry Todd, an author and expert in sports and exercise history, who with his wife, Jan, has collected a major archive of physical culture memorabilia at the University of Texas, is also skeptical. "Dynamic-Tension can build muscle only to a limited degree," Todd says. "To build up muscle you need weights. But back then it was hard to make money in weights. You needed something cheap to make and cheap to ship. Atlas wasn't the only one who saw the value of mail order."

In fact, a fellow bodybuilder says he saw Atlas lift weights when they worked out at a Brooklyn YMCA in the early 1940s. "I never saw Angie lift heavy," says Terry Robinson, referring to Atlas by another nickname. "He just did a lot of repetitions." Robinson did not hold it against him. Atlas "was always smiling," he says. "He never showed off. He was a humble guy."

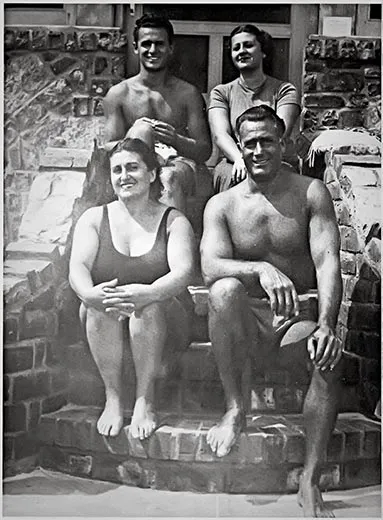

Atlas may have sneaked a few weight curls into his workouts, but as far as anyone knows he otherwise lived the virtuous life. He was an active promoter of the Boy Scouts. Asked for advice, he would say, "Live clean, think clean and don't go to burlesque shows." On the rare occasion when he dropped by a nightclub, usually in the company of Roman, he tried to talk the other patrons into switching to orange juice. And unlike Roman, who spent his growing fortune on luxury cars, yachts and private planes, Atlas had few known indulgences beyond a taste for white double-breasted suits. He lived in a four-room, fifth-floor Brooklyn apartment with his wife, Margaret, to whom he was singularly devoted, and his two children, Diana and Charles Jr. (Charles Jr. died last year of respiratory failure at age 89; Diana, now 89, declined to be interviewed for this article.) The family retreat was a modest home at Point Lookout on Long Island.

But he seemed to love the limelight. There are innumerable photos of Atlas hoisting bathing beauties or horsing around with boxers Max Baer and Joe Louis and golfer Gene Sarazen. He seemed to delight in publicity stunts, most of them engineered by Roman. He leashed himself to a 145,000-pound locomotive in a Queens railroad yard and towed it 112 feet. He entertained inmates at Sing-Sing (prompting the headline "Man Breaks Bar at Sing-Sing—Thousands Cheer, None Escape"). To protest an office dress code, he encouraged all the women on his staff to wear shorts to work in the summer. Then he appointed his private secretary president of the Long Live Shorts Club.

Atlas may have been more canny than he seemed. He never missed the chance to promote his business, whether posing with fans or lamenting the slovenly state of American manhood. A guest "appearance" with former heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey on a radio show in 1936, following a trip to England to open a London branch of the company, gives a flavor of Atlas' promotional skills:

Dempsey: Well, Charlie, I am certainly glad to see you safely back in the United States, but thought you might surprise us all by coming back on the German zeppelin.

Atlas: No, but if they ever reach the stage where they have flying gymnasiums I might do that, Jack.

Dempsey: How did you find the English people, Charlie? Did they seem to be in as good physical condition as our boys over here?

Atlas: On the contrary, they appeared in much better physical condition than our boys. The Englishman ... doesn't allow that chest of his to slip down below his belt, where you find most of the American chests. If some of the boys over here don't begin taking daily exercises, they'll be carrying their paunches around in baskets."

As the world prepared for the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin and the specter of National Socialism grew more alarming, Atlas bemoaned the poor state of U.S. distance running and touted the value of exercise to improve the readiness of American troops. "A study of the reasons for rejection of army applicants made by Atlas," read one syndicated newspaper story, "shows that nearly one-third of the defects are those which could be largely minimized by proper care and training." He was past the age to serve in the military, but he posed for a Treasury Department sale of Victory Bonds.

Though never a zealot like Macfadden, he was single-minded in trumpeting the value of health and the means to attain it. His exercises were framed with detailed lifestyle advice: on how to dress, sleep, breathe, eat and relax. (He urged "Music Baths.") He penned long treatises on various maladies, and his company published books on everything from child rearing to relationship advice. In his view, marriage itself was subject to the vagaries of a robust sense of well-being. "The lack of glorious, vigorous health," he noted, "would prove to be, if the divorce records were analyzed, the most common reason why so many marriages ‘crack up.'" He even counseled on the best way to start the day: "Get up immediately on awakening in the morning....Don't dillydally. GET UP!"

By the 1950s the business counted nearly a million pupils worldwide and the Dynamic-Tension regimen had been translated into seven languages. Ads in more than 400 comic books and magazines brought in 40,000 new recruits each year. Celebrity pupils included comedian Fred Allen, Rocky Marciano, Joe DiMaggio and Robert Ripley. (Ripley once wrote in his "Believe It or Not" column that he saw Atlas swim a mile through storm-tossed waters off a New York beach to tow a rowboat and its panicked occupants back to shore.)

Even as Atlas' days slipped into mundane routine, and he himself slipped into middle age, he would show up most afternoons at his Manhattan office to answer mail and preach fitness to fans who came by to view their idol in person. Dinner in Brooklyn was invariably broiled steak and fresh fruit and vegetables. He often ended the day practicing Dynamic-Tension in the mirror, though he also exercised regularly at the New York Athletic Club, where he was secure enough to offer marketing tips to potential rivals.

"I was working out at the club in the late '50s when I ran into Atlas," remembers Joe Weider, founder of Muscle & Fitness magazine and a former competitive bodybuilder then marketing barbells. "He came over to me and tried to offer me some business advice. He said a 100-pound barbell set was heavy to ship. Then he said, ‘Joe, I just send a course and some pictures, and I make so much more money than you. You should do that, too.'"

Atlas suffered a jarring blow in 1965 when Margaret died of cancer; he was so distraught he briefly considered joining a monastery. Instead, he fell back on what he knew best: tending to his body. He took long runs on the beach near Point Lookout. He bought a condominium in Palm Beach, Florida, and kept up a morning routine of 50 knee bends, 100 sit-ups and 300 push-ups. Occasionally a photo of him appeared, bronzed and flaunting his godlike chest, his measurements almost exactly the same as those enshrined in the Crypt of Civilization. In 1970, he sold his half of the company to Charles Roman but continued on as a consultant. On December 23, 1972, Charles Atlas died in a Long Island hospital of a heart attack. He was 79 years old.

It was the beginning of the fitness boom. The year Atlas died, maverick inventor Arthur Jones introduced his first Nautilus exercise machine, which offered variable resistance; it was joined on the workout floor by the Lifecycle exercise bike, which got its marketing kick from the budding science of aerobics. Other workout routines—Pilates, step aerobics, Spinning—would lure members to ever-multiplying health clubs. Charles Atlas Ltd., meanwhile, was selling the same mail-order course, but without Atlas as living icon and with neither branded equipment nor a franchised gym, the company profile dimmed. One day, Roman received a letter from Jeffrey C. Hogue, an Arkansas lawyer who said he'd idolized Atlas since the course rescued him from terminal insecurity decades earlier—and he wanted to buy the business.

"We met at the Players Club," Hogue recalls. "Mr. Roman told me how much [money] he wanted and I did something I advise no client ever to do. I didn't negotiate. It just didn't feel right."

Hogue declines to disclose the sale price, but he says he had to borrow a considerable portion of the money. The company's global reach surprised him, he says—he recounts that the first letter he opened was from a student in Nepal—but it was making only a modest profit.

And then the Internet brought Charles Atlas back to life.

It turned out the World Wide Web was the perfect marketing tool: cheaper even than the back pages of comics, international in scope, the ideal vehicle for mail- order sales. Seemingly immune from inflation—the course now sells for $49.95, only $20 more than in the early 1930s—Atlas' promise to "Make You a New Man!" was only a click away in banner ads on youth-oriented sites. The company says it now does 80 percent of its business online. "We are literally overwhelmed by the Web site activity," says Hogue, who declines to provide figures on revenue or growth. And such high-profile brands as the Gap, Mercedes and IBM have licensed the Atlas image or "Hey, Skinny!" comic strips for retro advertisements.

Charles Atlas came from a simpler time. His publicity stunts would hardly have interested today's celebrity magazines. He neither drank nor smoked, and his personal life was free of scandal. Steroids, had they been available then, would not have interested him. He sprang from the back pages of comic books and promised every bullied, insecure young man the means to take control of his life.

If he hadn't been real, no one would have believed him.

Jonathan Black wrote Yes, You Can! (2006), about motivational speaking. He is now at work on a book on fakery.

Editor's Note: This article has been revised to make the following corrections: The name of the co-author of Yours in Perfect Manhood is Charles Gaines. Fellow bodybuilder Terry Robinson used the nickname of "Angie" to refer to Charles Atlas.