Clarence Dally — The Man Who Gave Thomas Edison X-Ray Vision

“Don’t talk to me about X-rays,” Edison said after an assistant on one of his X-ray projects started showing signs of illness. “I am afraid of them.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120314084032Thomas-Edison-Fluoroscope-1896-470.jpg)

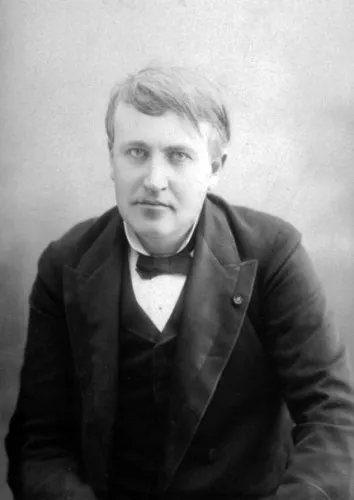

Thomas Alva Edison’s sprawling complex of laboratories and factories in West Orange, New Jersey, was a place of wonderment in the late 19th century. Its machinery could produce anything from a locomotive engine to a lady’s wristwatch, and when the machines weren’t running, Edison’s “muckers” —the researchers, chemists and technologically curious who came from as far away as Europe—might watch a dance performed by Native Americans from Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show in the inventor’s Black Maria movie studio or hear classical musicians recording on Edison’s wax cylinder phonographs.

The muckers happily toiled through 90-hour work weeks, drawn by the allure of the future. But they also faced the perils of the unknown—exposure to chemicals, acids, electricity and light. No one knew this better than Edison mucker Clarence Madison Dally, who unwittingly gave his life to help develop one of the most important innovations in medical diagnostic history. When it became apparent what Dally had done to himself in the name of research, Edison walked away from the invention. “Don’t talk to me about X-rays,” he said. “I am afraid of them.”

Born in 1865, Dally grew up in Woodbridge, New Jersey, in a family of glassblowers employed by the Edison Lamp Works in nearby Harrison. At 17 he enlisted in the Navy, and after serving six years he returned home and worked beside his father and three brothers. At age 24, he was transferred to the West Orange laboratory, where he would assist in Edison’s experiments on incandescent lamps.

In 1895, the German physicist Wilhelm Roentgen was experimenting with gas-filled vacuum tubes and electricity; that November he observed a green fluorescent light coming from a tube that had been wrapped in heavy black paper. He’d stumbled, quite accidentally, onto an unknown type of radiation, which he named an “X-ray.” A week later, Roentgen made an X-ray image of his wife’s hand, revealing finger bones and a bulbous wedding ring. The image was quickly circulated around the world to a dazzled audience.

Edison received news of the discovery and immediately set out to experiment with his own fluorescent lamps. He’d been known for his background in incandescent lamps, where electricity flowed through filaments, causing them to heat and glow, but Edison had a newfound fascination with the chemical reactions and gasses in Roentgen’s fluorescent tubes and the X-rays he had discovered. Equally fascinated, Clarence Dally took to the work enthusiastically, performing countless tests, holding his hand between the fluoroscope (a cardboard viewing tube coated with fluorescent metal salt) and the X-ray tubes, and unwittingly exposing himself to poisonous radiation for hours on end.

In May 1896, Edison, along with Dally, went to the National Electric Light Association exhibition in New York City to demonstrate his fluoroscope. Hundreds lined up for the opportunity to stand before a fluorescent screen, then peer into the scope to see their own bones. The potential medical benefits were immediately apparent to anyone who saw the display.

Dally returned to Edison’s X-ray room in West Orange and continued to test, refine and experiment over the next few years. By 1900, he began to show lesions and degenerative skin conditions on his hands and face. His hair began to fall out, then his eyebrows and eyelashes, too. Soon his face was heavily wrinkled, and his left hand was especially swollen and painful. Like a faithful mucker committed to science, Dally found what he thought was the solution to prevent further damage to his left hand: He began using his right hand instead. The result might have been predictable. At night, he slept with both hands in water to alleviate the burning. Like many researchers at the time, Dally assumed he’d heal with rest and time away from the tubes.

In September 1901, Dally was asked to travel to Buffalo, New York, on a matter of national importance. One of Edison’s X-ray machines, which was on display there at the Pan-American Exposition, might be needed. President William McKinley had been about to give a speech at the exposition when an anarchist named Leon Czolgosz darted toward him, a pistol concealed in a handkerchief, and fired twice, hitting McKinley in the abdomen.

Dally and a colleague arrived in Buffalo and quickly set about installing the X-ray machine in the Millburn House, where McKinley had been staying, while the president underwent surgery at the Exposition hospital. One of the bullets had merely grazed McKinley and was discovered in his clothing, but the other had lodged in his abdomen. Surgeons couldn’t locate it, but McKinley’s doctors deemed the president’s condition too unstable for him to be X-rayed. Dally waited for McKinley to improve so that he might guide the surgeons to the hidden bullet, but that day never came: McKinley died a week after he had been shot. Dally returned to New Jersey.

By the following year, the pain in Dally’s hands was becoming intolerable, and they looked, some people said, as if they’d been scalded. Dally had skin grafted from his leg to his left hand several times, but the lesions remained. When evidence of carcinoma appeared on his left arm, Dally agreed to have it amputated just below his shoulder.

Seven months later, his right hand began to develop similar problems; surgeons removed four fingers. When Dally—who had a wife and two sons—couldn’t work anymore, Edison kept him on the payroll and promised to take care of him for as long as he lived. Edison put an end to his experiments with Roentgen’s rays. “I stopped experimenting with them two years ago, when I came near to losing my eyesight, and Dally, my assistant, practically lost the use of both of his arms,” Edison would tell a reporter from the New York World. “I am afraid of radium and polonium too, and I don’t want to monkey with them.”

When an oculist informed him that his “eye was something over a foot out of focus,” Edison said, he told Dally “that there was a danger in the continuous use of the tubes.” He added, “The only thing that saved my eyesight was that I used a very weak tube, while Dally insisted in using the most powerful one he could find.”

Dally’s condition continued to deteriorate, and in 1903, doctors removed his right arm. By 1904, his 39-year-old body was ravaged by metastatic skin cancer, and Dally died after eight years of experimenting with radiation. But his tragic example eventually led to a greater understanding of radiology.

Edison, for his part, was happy to leave those developments to others. “I did not want to know anything more about X-rays,” he said at the time. “In the hands of experienced operators they are a valuable adjunct to surgery, locating as they do objects concealed from view, and making, for instance, the operation for appendicitis almost sure. But they are dangerous, deadly, in the hands of inexperienced, or even in the hands of a man who is using them continuously for experiment.” Referring to himself and to Dally, he said, “There are two pretty good object-lessons of this fact to be found in the Oranges.”

Sources

Articles: “Edison Fears Hidden Perils of the X-Rays,” New York World, August 3, 1903. ”C.M. Dally Dies a Martyr to Science,” New York Times, October 4, 1904. “Clarence Dally: An American Pioneer,” by Raymond A. Gagliardi, American Journal of Roentgenology, November, 1991, vol. 157, no. 5, p. 922. ”Radiation-Induced Meningioma,” by Felix Umansky, M.D., Yigal Shoshan, M.D., Guy Rosenthal, M.D., Shifra Fraifield, M.B.A., Sergey Spektor, M.D., PH.D., Neurosurgical Focus, American Association of Neurological Surgeons, June 26, 2008. ”American Martyrs to Radiology: Clarence Madison Dally, (1865-1904)” by Percy Brown, American Journal of Radiology, 1995. “This Day in Tech: Nov. 8, 1895: Roentgen Stumbles Upon X-Rays,” by Tony Long, Wired, November 8, 2010.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)