The Coast Guard’s Most Potent Weapon During Prohibition? Codebreaker Elizebeth Friedman

A pioneer of her time, Friedman was a crucial part of the fight to enforce the ban on booze

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c9/08/c9082da4-1b21-4500-bfdd-87f323d01972/ih173946.jpg)

On April 11, 1931, during the height of Prohibition, federal agents raided the New Orleans headquarters of a Vancouver-based liquor ring. They arrested nine people and issued warrants for 100 more, including four members of Al Capone’s Chicago gang and at least a few Mississippi deputy sheriffs. For two years, investigators had watched, listened to, read, and deciphered the activities of four distilleries, united in New Orleans as one of the most powerful rum rings.

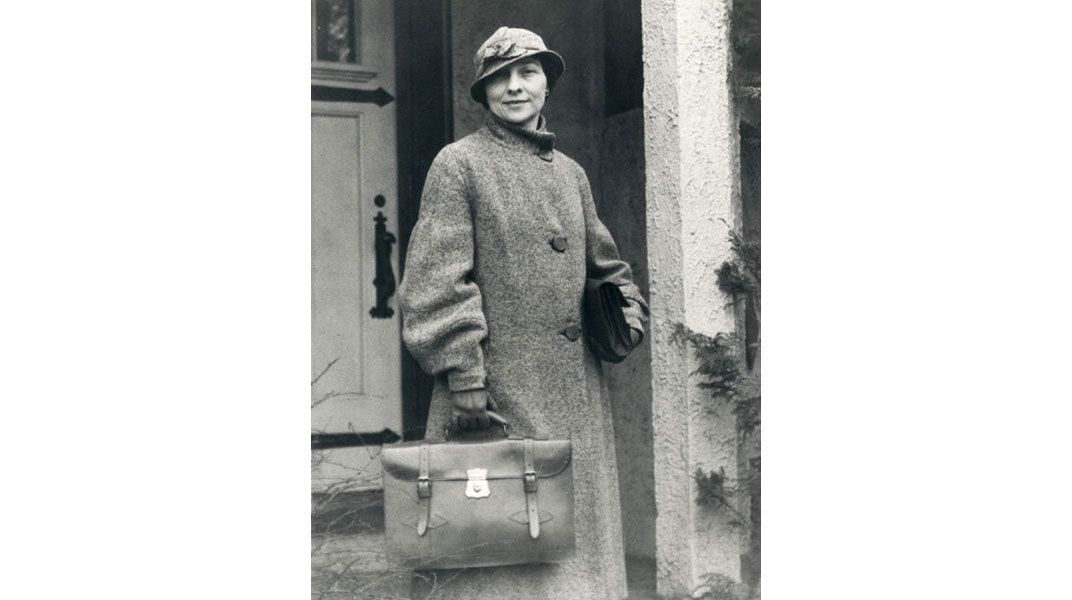

A grand jury indicted 104, and in 1933, Colonel Amos W. Woodcock, Special Assistant to the Attorney General, led the prosecution against 23 members of what he called "the most powerful international smuggling syndicate in existence, controlling practically a monopoly of smuggling in the Gulf of Mexico and on the West Coast." His star witness was a five-foot-tall Coast Guard codebreaker named Elizebeth Friedman.

The government knew how the ring operated: smugglers hid liquor on rum runners carrying legal cargo, shipped them down the Pacific and Atlantic coasts, and at rendezvous points outside of United States waters (12 miles, or a one-hour's sail away from the shore), unloaded cases onto high-speed boats. The motorboats carried the liquor to Mississippi deltas or Louisiana bayous, where smugglers then packed the booze as lumber shipments and drove them to the Midwest.

To convict the accused, Woodcock had to link them to hundreds—if not thousands—of encrypted messages that passed between at least 25 separate ships, their shore stations, and the headquarters in New Orleans. Defense attorneys demanded to know how the government could prove the content of enciphered messages. How, for example, could a cryptanalyst know that "MJFAK ZYWKB QATYT JSL QATS QXYGX OGTB" translated to "anchored in harbor where and when are you sending fuel?"*

Elizebeth Friedman, the prosecution's star witness, asked the judge to find a chalkboard.

Using a piece of chalk, she stood before the jury and explained the basics of cryptanalysis. Friedman talked about simple cipher charts, mono-alphabetic ciphers and polysyllabic ciphers; she reviewed how cryptanalysts encoded messages by writing keywords in lines of code, enclosing them with letter patterns that could be deciphered with the help of various code books and charts rooted in the schemes and charts of centuries past.

The defense did not want her to stay on the stand for long.

"Mrs. Friedman made an unusual impression," Colonel Woodcock later wrote to the Secretary of the Treasury, whose department oversaw the Coast Guard. "Her description of the art of deciphering and decoding established in the minds of all her entire competency to testify." Woodcock commented on the role of military intelligence in cracking the case, stating that the Coast Guard, with its control of radio intelligence and cryptanalysis, "is the only agency of the Government connected with law enforcement which has such an extremely valuable section." When "that valuable section" of the Coast Guard began, it had two employees—Friedman and an assistant.

When Friedman first joined the Guard, the agency employed neither uniformed nor civilian women. Savvy, quick-witted and stoic, she weighed some of the 20th century's most difficult ciphers: her findings nailed Chinese drug smugglers in Canada, identified a Manhattan antique doll expert as a home-grown Japanese spy, and helped resolve a diplomatic feud with Canada.

Friedman's work as a cryptanalyst began in 1916, when she went to work for Riverbank, a privately run Illinois laboratory-turned-think tank during World War I. Three years earlier, she had graduated from Hillsdale College with a degree in English, and she didn't know what to do with herself. Elizebeth (née) Smith was the youngest of nine children, and her father, a wealthy Indiana dairy farmer, hadn't wanted her to pursue higher education. She went anyway, borrowing the tuition from him at a six percent interest rate. After graduation, she spent time in Chicago, where friends encouraged her to visit the Newberry Library, which held one of Shakespeare's first folios. A librarian there told her that a wealthy man named George Fabyan was looking for a young, educated contributor to a Shakespearean research project.

Before long, Elizebeth Smith was living at Riverbank Laboratory, an estate owned by Fabyan in Geneva, Illinois. It's where she also met her future husband, William Friedman, who worked for Riverbank as a geneticist. Both collaborated on a project that attempted to prove that Sir Francis Bacon, a cryptologist himself, had authored Shakespeare's plays ("Decoding the Renaissance," a current exhibit at the Folger Shakespeare Library, features the Friedman's scholarship on the topic.)

Within two years, Fabyan, a rich businessman with an outsized sense of his own self-worth, convinced the government to allow his team of cryptanalysts to specialize in decoding encryptions for the War Department. In unpublished memoir notes available through the George C. Marshall Foundation, Elizebeth Friedman speaks of her initial shock at the assignment: "So little was known in this country of codes and ciphers when the United States entered World War I, that we ourselves had to be the learners, the workers and the teachers all at one and the same time."

In 1921, the War Department asked the young couple to move to Washington. Elizebeth loved the town—deprived of cultural events during her adolescence, she remembered going to the theater multiple times a week when she arrived. Both had jobs as contractors specializing in code breaking: Elizebeth earned half of what her husband made. As William Friedman started in the Army’s Signal Corps and on a path towards becoming a lieutenant colonel and the chief cryptologist of the Department of Defense, "Mrs. Friedman" moved among various agencies of the Treasury Department.

The armed service, which turns 100 today, formed on January 28, 1915, when President Woodrow Wilson united the Revenue Cutter and the Lifesaving Services as "the Coast Guard." Operating under the Treasury and functioning as part of the Navy during wartime, the Coast Guard combined the similar maritime services offered by its predecessors.

Prior to Prohibition, the Coast Guard protected American interests largely by supervising customs and maritime regulations in coastal waters. But as an arm of the Treasury, the Coast Guard became responsible for enforcing Prohibition enforcement on the seas, fighting piracy and smuggling in territorial waters once enforcement of the Volstead Act began in January, 1920.

Five years into the Prohibition era, Captain Charles Root, an intelligence officer with the Guard spoke with Elizebeth about participating in a counterintelligence unit. Their initial choice was her husband, but William wanted to stay at the Signal Corps, where he was working to advance the military’s ability to encode and decode messages. The job went to Elizebeth. She understood the unpopular public perception of the work she was about to do.

"The government law enforcement agencies had no more taste for [enforcing Prohibition] than the public who loved their drink," she wrote. "But the government officials, who with minor exceptions were honest at least, had no choice but to pursue the rigid torturous paths of attempting to defeat the operations of the criminal gangs who were so intent on mulcting the public."

Hundreds of messages in Coast Guard intelligence waited to be deciphered by Friedman. She and one aide worked through them in two months. Friedman was surprised that rum runners operated on simple encryptions, using words like "Havana" as obvious key indicators. "When choosing a key word," she wrote, "never choose one which is associated with the project with which one is engaged."

But between the second half of 1928 and 1930, the smugglers advanced from using two cryptosystems to 50 different codes. Patiently and persistently, Friedman and her clerk cracked 12,000 encryptions. At least 23 had to do with the I'm Alone, whose fate led to a short chapter in American history involving diplomatic tensions with Canada.

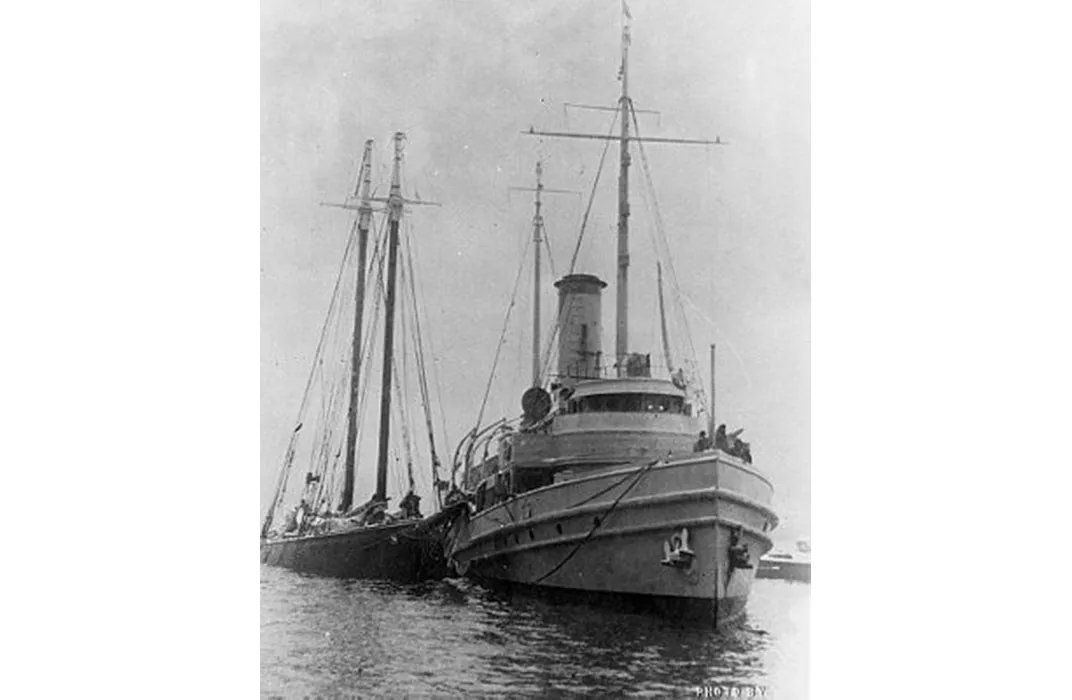

On March 20, 1929, at 6:30 a.m., the USCG Wolcott spotted the I'm Alone off the coast of Louisiana. This particular two-masted rum runner had taunted the Coast Guard along the New England and New York coasts for six years, ever since it was built in Nova Scotia. Records show that between December of 1925 and the spring of 1929, the Coast Guard had tracked the ship's movements almost daily. That day, the Wolcott was armed with the knowledge that the ship had recently picked up liquor in Belize with the intention to drop at rendezvous points in the Gulf of Mexico.

The Wolcott trailed the I'm Alone for a day while waiting for backup. The USCG Dexter arrived the morning of March 22. Two-hundred-and-twenty miles off the Gulf Coast, the two cutters cornered and fired upon the I'm Alone, tearing apart the ship's hull, and more dramatically, the Canadian flag hoisted on the mast. As the boat sunk, the Dexter rescued the 8- man crew from the water; it failed, though, to resuscitate one man, a French boatswain.

The incident angered the international community, particularly Canada, the United Kingdom and France. (At this time, Canada, while internally self-governing, was part of the British Empire). Less than a year before, the British had warned Americans about following rumrunners into their territorial waters off the Bahamas. Canadian ambassador Vincent Massey said the I’m Alone incident questioned the freedom of the seas.

The Canadian government filed a claim against the United States for $386,803.18, which included damages for the ship, its cargo (including the liquor), and personnel losses. The United States said that because the Wolcott's chase started within U.S. waters, it was not at fault. Canada argued that two cutters could not have legally pursued the I'm Alone so far for so long. The two countries took the case to international arbitration.

Back in her office, Elizebeth Friedman was at work. She and her staff of one concentrated on 23 messages sent from Belize to "harforan," an address in New York. Operating on an earlier theory, she proved that while Canadians may have built and registered the I'm Alone, its owners were Americans. And judging from the content of the telegrams, they had clear intent to smuggle liquor into Louisiana. Once it was established that Americans had pursued their own ship, arbitrators awarded Canada a public apology from the U.S. for firing on the Canadian flag, and a fine of $50,665.50, nearly $336,000 less than its claim.

Citing the I'm Alone case as an example, in 1930, Elizebeth Friedman and her boss, lieutenant commander F. J. Gorman, head of Coast Guard intelligence, proposed a permanent place for a cryptanalytic unit in the Coast Guard, as opposed to a different agency in the Treasury, Customs, or Justice Departments. This execution would allow the Coast Guard to move beyond recording and deciphering codes to intervening in smuggling operations as they unfolded. Friedman became the head of a unit of six, and one year later, it was a Coast Guard intelligence office stationed in Mobile that intercepted hundreds of the radio messages that incriminated Al Capone’s liquor smuggling group.

The New Orleans trial put the spotlight on Elizebeth Friedman – but she didn't want it. She didn't like how newspaper accounts differed in their delivery of facts – one referred to her as a "pretty middle aged woman" and another as "a pretty young woman." She didn't like "frivolous adjectives," and she didn't like reading quotes of hers that she remembered saying differently. But perhaps it wasn't the frivolity of prose that bothered her as much as the reason for its attention: she was a smart woman, and the backhandedness of this supposed compliment threatened to render it as an anomaly.

The men—the officers, the Commandants and judges and district attorneys—respected her as a colleague. "Many times I've been asked as to how my authority, that is the direction and superior status of a woman as instructor, teacher, mentor and slave driver to men, even to commissioned and non-commissioned officers, by these men was accepted. I must declare with all truth that with one exception, all of the young men younger or older who have worked for me and under me and with me have been true colleagues."

Elizebeth Friedman retired in 1946 (William did the same several years later), and in 1957, they published the Shakespearean scholarship that had brought them together at Riverbank Laboratory before they were married. (They concluded that contrary to their former boss' insistence, the cipher defends William Shakespeare's authorship.) William Friedman died in 1969, and Elizebeth in 1980. In 1974, the Coast Guard was the first armed service to allow women to enter the officer candidate program.

*Credit goes to Dr. David Joyner for piecing together this piece of Elizebeth Friedman’s analysis in his work "Elizebeth Smith Friedman, up to 1934" (see page 15).

Thanks to Jeffrey S. Kozak, Archivist & Assistant Libarian at the George C. Marshall Foundation, and to military historian Stephen Conrad, for research assistance.

Editor's note, February 17, 2015: Insights provided by Hofstra professor G. Stuart Smith suggest that Friedman did not assist in cracking a Japanese cryptograph known as "PURPLE," as this story originally stated. We have removed that sentence from the article.