Conquering Everest

A history of climbing the world’s tallest mountain

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/everest-631.jpg)

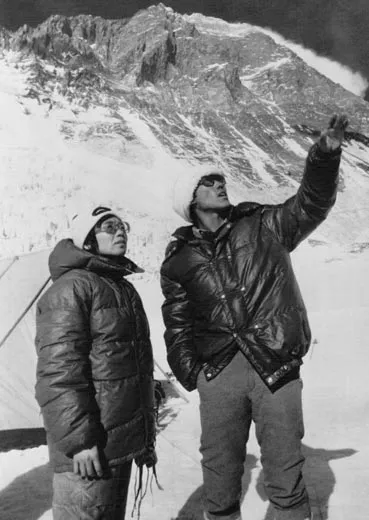

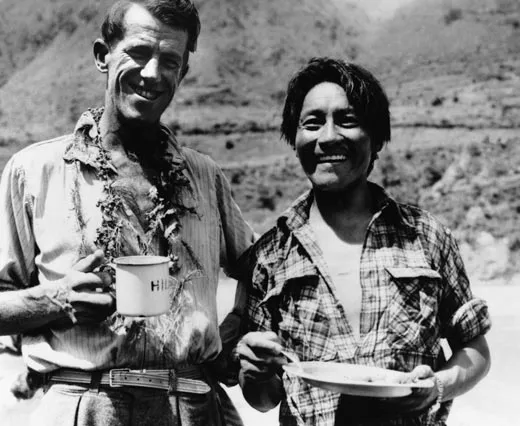

On May 29, 1953, Edmund Hillary, a 33-year-old beekeeper from New Zealand and his Nepalese-born guide Tenzing Norgay, stood at the top of Everest for the first time in history. The pair hugged, snapped some evidentiary photographs and buried offerings in the snow. They also surveyed the area for signs of George Mallory and Andrew Irvine, two climbers who disappeared in 1924. When met by climbing colleague George Lowe on the descent to camp, Hillary brashly reported the achievement: "Well, George, we knocked the bastard off."

Conquering the 29,035-foot monolith ultimately earned Hillary a knighthood and Tenzing Britain's esteemed George Medal for courage. Hillary later wrote: "When we climbed Everest in 1953 I really believed that the story had finished." Indeed, he and Tenzig never relived the expedition in conversations with one another and neither attempted the climb again.

Of course, that's not to say others haven't. In the wake of Sir Edmund Hillary's death at the age of 88 on January 11, 2008, we're reminded of the frontier he and Tenzing opened and of the 3,500-plus climbers who have since staked their claim in the world's tallest mountain.

One such climber is Everest guide Dave Hahn of Taos, New Mexico. The 46-year-old has made his name in Everest history by summiting nine times, a record among Westerners that he shares with one other climber. (He humbly admits that nine pales in comparison to Apa Sherpa's world record 17 ascents.) He also guided a 2006 expedition in which world champion freeskier Kit DesLauriers become the first to ski down all 'Seven Summits'.

The highlight of Hahn's career came in 1999 when his American expedition located George Mallory's body. He captured the moment the team turned over a clothing tag labeled "G. Mallory" on film, describing the experience as "a moment few can compare to." On climbing Everest, Hahn says: "It's about getting a closer look at or appreciating what others have done – about experiencing the history."

Pioneering Climbs

Mount Everest made its cartographic debut as the world's highest mountain in 1856, and British army officers began discussing the possibility of climbing it in the 1890s. The Royal Geographic Society and Alpine Club carried out the first expedition in 1921. Six more unsuccessful British attempts up the northern route followed, with climbers Mallory and Irvine thought to have reached just shy of the summit. World War II put a halt to the attempts and when China usurped Tibet in 1950, the northern approach became off limits.

The British received permission from Nepal to explore the southern route in a 1951 expedition that served as Edmund Hillary's introduction to the region. A year later, Tenzing Norgay, then one of the most experienced Sherpas, made an attempt with the Swiss. Hillary and Tenzing joined forces when they were both recruited for a Royal Geographical Society and Alpine Club-sponsored expedition. The two eyed each other for a summit bid and nailed the historic first ascent.

One of the photographs Hillary took at the summit in May 1953 was of Tenzing waving his ice pick attached with the flags of the United Nations, Britain, India and Nepal. The gesture set the bar for other countries. Swiss, Chinese, American and Indian teams summited in 1956, 1960, 1963 and 1965, respectively.

The next challenge was forging new routes. All but the Chinese, who ascended the northern route, had stuck largely to the British route up the Southeast Ridge. But between the 1960s and 1980s, Everest's formidable West Ridge, Southwest Face and East Face were tackled.

Others continued to expand the definition of what was possible on Everest. Japanese climber Tabei Junko became the first woman to climb Everest in May 1975, backed by an all-female (besides the sherpas) expedition.

Other climbers sought challenge in climbing techniques. On May 8, 1978, Italian Reinhold Messner and his Austrian climbing partner Peter Habeler scaled Everest without supplemental oxygen. They trudged at a pace of 325 feet per hour in the final stretch to break a 54-year, sans-oxygen record of 28,126 feet. Messner went on to complete the first solo climb of the mountain in 1980, an endeavor that left him, as he described, "physically at the end of my tether."

Messner's successors used Everest as a testing ground for their limits as well. A Polish team completed the first winter ascent in 1980, and two Swiss climbers—Jean Troillet and Erhard Loretan—broke record times in 1986, climbing the North Face in 41.5 hours and descending in 4.5 hours. Two years later, French climber Jean-Marc Boivin paraglided from the summit. American Erik Weihenmayer, who is blind, defied his own physiological challenge to summit in 2001.

Commercialization of Everest

The number of Everest ascents ballooned from 200 in 1988 to 1,200 by 2003. Multiple ascents per day became common, and it was reported that nearly 90 people were successful on a single day in May 2001. The growing numbers irk traditionalists. Even Hillary scorned the apparent trivialization of the pursuit during the 50th anniversary celebration of his climb in 2003, when he witnessed hundreds of so-called mountaineers drinking at base camp.

A high-profile disaster in 1996 in which several teams descended in a harrowing storm roused the commercialism debate. Eight men died, and climber Jon Krakauer survived to write his 1997 bestseller Into Thin Air, which publicized that some wealthy amateur climbers paid as much as $65,000 to participate, putting themselves and their guides in serious jeopardy.

Hillary once remarked: "I feel sorry for today's climbers trying to find something new and interesting to do on the mountain, something that will get both the public attention and the respect of their peers. Up and down the mountain in 24 hours, a race to the top—what will they think of next?"

A Test for the Ages

Everest's history seems to prove that as long as there's an edge, there are people who want to live on it, both in the manner that others have laid out before them and in ways that redefine the experience.

There's Hahn, a purist who sometimes feels like a one-trick pony for going back to climb Everest again and again. "You'd think that I might have gotten enough from Everest, but I haven't," says Hahn. "I'm not done getting whatever it has to teach me." Then there's DesLauriers. What may seem stunt-like to others is natural for her: "I never thought about 'doing something new.' It's just that I like to ski down mountains that I climb up." Either way, their attempts and their stories are testaments to Everest's staying power as a worthy adversary.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)