Debating on Television: Then and Now

Kennedy and Nixon squared off in the first televised presidential debate decades ago and politics have never been the same

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Kennedy-Nixon-television-debate-631.jpg)

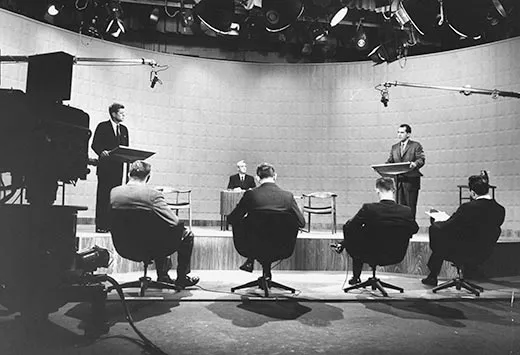

A little more than half a century ago, American politics stumbled into a new era. In WBBM-TV studios in Chicago on September 26, 1960, presidential candidates Richard M. Nixon and John F. Kennedy stood before cameras and hot lights for the first-ever televised presidential debate. An extraordinary 60 percent of adults nationwide tuned in. This encounter—the first of four—boosted support for Kennedy, a little-known Massachusetts senator and political scion who would go on to win the White House. Elections in the United States would never be the same again. No single aspect of presidential campaigns attracts as much interest as televised debates, and they have provided some of the most memorable moments in modern political history.

In 1960, Nixon, then vice president, was expected to perform brilliantly against Kennedy, but few politicians have ever bombed so badly. The striking contrast of their images on the television screen made all the difference. Nixon, who had recently been in the hospital with a knee injury, was pale, underweight, and running a fever, while Kennedy, fresh from campaigning in California, was tanned and buoyantly energetic. Before they went on the air, both candidates refused the services of a cosmetician. Kennedy’s staff, however, gave him a quick touch up. Nixon, cursed by a five o’clock shadow, slapped on Lazy Shave, an over-the counter powder cover-up. It would only heighten his ghastly pallor on the TV screen. Voters who listened to the debate on the radio thought Nixon performed just as expertly as Kennedy, but TV viewers could not see beyond his haggard appearance.

Sander Vanocur, who was a member of the press panel with NBC for that premier debate, says today that he was too caught up in the moment to notice Nixon’s illness, but he recalls that the vice president “seemed to me to be developing some sweat around his lips.” One thing, however, was unmistakable, Vanocur says: “Kennedy had a sure sense of who he was, and it seemed to radiate that night.” Countless viewers agreed. Later, Kennedy said that he never would have won the White House without the televised debates, which so effectively brought him into the living rooms of more than 65 million people.

There were three further debates, but they hardly mattered, says Alan Schroeder, professor of journalism at Northeastern University and a historian of presidential debates. “Kennedy left such a positive impression in the first debate, it was quite difficult for Nixon to overcome it.” No election rules require candidates to debate. After his dismal performance in 1960, Nixon refused to participate in 1968 and 1972. More recently, John McCain tried to cancel one of his matchups with Barack Obama in 2008, saying that he had urgent business back in Washington. But over the years, the public has come to expect that candidates will be courageous enough to face each other on television, live and unscripted.

Tens of millions of viewers tune in to watch debates, and advocates call them indispensable for helping undecideds make up their minds. “If the campaign is a job interview with the public,” says Charlie Gibson, moderator for the 2004 Bush-Kerry contest, then debates are a priceless chance “to compare styles, to get a sense of their ease with issues.” In several elections, debates have dramatically shifted voter perceptions and even, some experts argue, changed the outcome of the race.

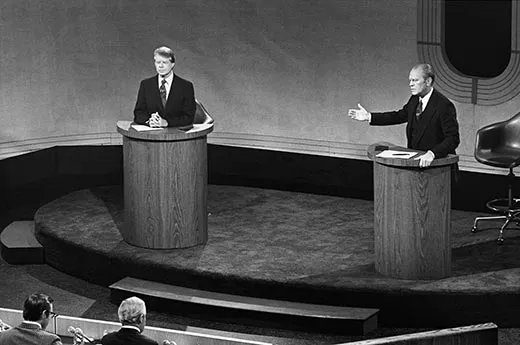

Jimmy Carter rode a post-debate spike in the polls to narrowly beat Gerald Ford in 1976, for example, and Al Gore's erratic performance in 2000 contributed to his loss to George W. Bush that November in one of the closest elections ever. “Debates have a very powerful effect on how candidates are perceived,” says Schroeder, “and in giving voters confidence they are making the right decision.”

Partly because they exert such great influence, televised debates have always received heated criticism. Some complain that the answers tend to be superficial, that charisma trumps substance, that pundits needlessly obsess about minor goofs. Certainly the stakes are sky-high. “It’s a long walk from the dressing room to the debate platform,” says Walter Mondale, a veteran of several debates. “You know if you screw up that you’ll live with it the rest of your life.” No wonder candidates fight to keep formats short and free from messy interpersonal exchanges—although these sometimes happen anyway, as when Lloyd Bentsen contemptuously told Dan Quayle in the 1988 vice-presidential debate, “You’re no Jack Kennedy,” to which a stunned-looking Quayle replied, “That was really uncalled for!”

Little spats like this one are catnip to the media, who habitually cover debates as if they were sporting events, with clear winners and losers. “They’re trying to make it a political prizefight,” says John Anderson, who debated Ronald Reagan as an Independent in 1980. “They want to see a candidate throw a sucker punch.” It’s this mentality that causes commentators to magnify every blunder: in 1992, for example, George H.W. Bush repeatedly glanced at his watch during a town hall debate with Bill Clinton and Ross Perot, and pundits had a field day. “That criticism was unfair,” says former Gov. Michael Dukakis, who debated Bush in 1988 and was watching again that night. “In a long debate, you’ve got to have a sense of where you are—so there’s nothing strange about a guy looking at his watch. But it hurt him.”

By appearing bored and impatient, Bush inadvertently reinforced his own image as an aloof patrician. Many debaters have similarly damaged themselves by confirming what voters already feared—Carter seemed touchy-feely in 1980 when he implied that his young daughter, Amy, advised him on nuclear arms; Gore, supercilious when he loudly sighed in 2000; McCain, angry when he dismissively called Obama “That One” in 2008. Such episodes are so common, we tend to remember debates not for what went right, but what went wrong.

Fifty years after Nixon’s fatal debate debut, a similar upset played out recently in Great Britain, where televised debates were introduced this spring for the first time ever in a general election. Nick Clegg, 43, a little-known candidate from the small third-place Liberal Democrats Party, performed spectacularly in debate against two better-known rivals. After the first encounter, his personal approval ratings skyrocketed to 78 percent, the highest ever seen in Britain since Churchill’s in World War II. As with Kennedy in 1960 (also just 43), the public could suddenly envision the energetic Clegg as a national leader.

Today the Liberal Democrats share power with the Conservatives, and Clegg is deputy prime minister—an outcome few could have imagined before the debates. In Britain as in America, televised debates promise to exert a potent influence over political life, permanently changing the campaign landscape. For all their riskiness and high drama, they play a crucial role now and are doubtless here to stay.