Demolishing Kashgar’s History

A vital stop on China’s ancient Silk Road, the Uighur city of Kashgar may lose its old quarter to plans for “progress”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/construction-around-old-mosque-Kashgar-631.jpg)

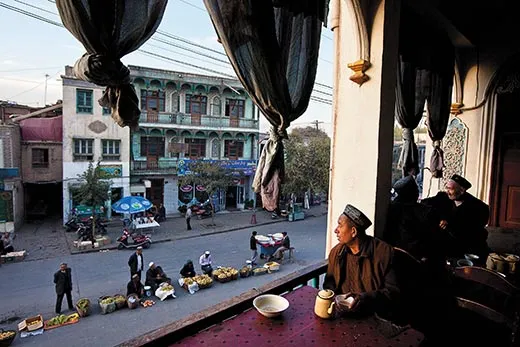

The second-story rooms of the centuries-old mud-brick houses were cantilevered atop log beams and nearly touched each other across an alleyway paved with hexagonal stones. Women wearing dark veils leaned out of tiny windows. Poplar doors, painted bright blue or green and adorned with brass floral petals, stood half open—a subtle signal that the master of the house was inside. The aromas of freshly baked bread and ripe peaches wafted up from vendors’ wooden carts.

It was early morning and I was exploring the back streets of Kashgar, a fabled city on the western edge of China, with a Chinese journalist from Beijing, whom I’ll identify only as Ling, and a young handicraft salesman from Kashgar, whom I’ll call Mahmati. Mahmati is a Uighur (WEE-goor), a member of the ethnic minority that makes up 77 percent of the Kashgar population. He had traveled to Beijing before the 2008 Olympics to take advantage of the tourist influx and had stayed on. I’d invited him to accompany me to Kashgar to act as my guide to one of the best-preserved—and most endangered—Islamic cities in Central Asia.

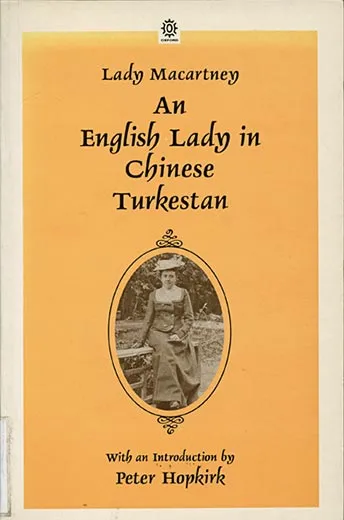

The three of us followed narrow passageways bathed in sunlight or obscured by shadows. We encountered faces that testified to Kashgar’s role as a crossroads of Central Asia on the route linking China, India and the Mediterranean. Narrow-eyed, white-bearded elders wearing embroidered skullcaps chatted in front of a 500-year-old mosque. We passed pale-complexioned men in black felt hats; broad-faced, olive-skinned men who could have passed for Bengalis; green-eyed women draped in head scarfs and chadors; and the occasional burqa-clad figure who might have come straight from Afghanistan. It was a scene witnessed in the early 1900s by Catherine Theodora Macartney, wife of the British consul in Kashgar when it was a listening post in the Great Game, the strategic Russia-Britain conflict for control of Central Asia. “One could hardly say what the real Kashgar type was,” she wrote in a 1931 memoir, An English Lady in Chinese Turkestan, “for it has become so mixed by the invasion of other people in the past.”

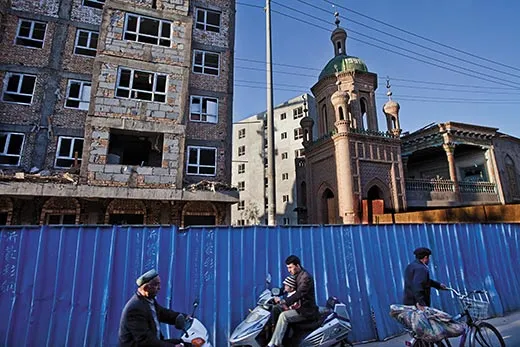

We rounded a corner and stared into a void: a vacant lot the size of four football fields. Mounds of earth, piles of mud bricks and a few jagged foundations were all that remained of a once-lively neighborhood. “My God, they are moving so fast,” Mahmati said. A passerby pointed to a row of houses at the lot’s edge. “This is going next,” he told us. Nearby, a construction team had already laid out the steel and concrete foundations of a high-rise and was dismantling the surrounding buildings with mallets and chisels. The men stood on ladders, filling the air with dust. A red banner announced the quarter would be rebuilt with “true care from the [Communist] Party and the government.”

For more than a thousand years, Kashgar—where the bone-dry Taklamakan Desert meets the Tian Shan Mountains—was a key city along the Silk Road, the 7,000-mile trade route that connected China’s Yellow River Valley with India and the Mediterranean. In the ninth century, Uighur forebears, traders traveling from Mongolia in camel caravans, settled in oasis towns around the desert. Originally Buddhists, they began converting to Islam about 300 years later. For the past 1,000 years, Kashgar has thrived, languished—and been ruthlessly suppressed by occupiers. The Italian adventurer Marco Polo reported passing through around 1273, about 70 years after it was seized by Genghis Khan. He called it “the largest and most important” city in “a province of many towns and castles.” Tamerlane the Great, the despot from what is now Uzbekistan, sacked the city in 1390. Three imperial Chinese dynasties conquered and reconquered Kashgar and its environs.

Still, its mosques and madrassahs drew scholars from all over Central Asia. Its caravansaries, or inns, provided refuge to traders bearing glass, gold, silver, spices and gems from the West and silks and porcelain from the East. Its labyrinthine alleys teemed with blacksmiths, cotton-spinners, book-binders and other craftsmen. Clarmont Skrine, a British envoy writing in 1926, described looking out on “the vast horizon of oasis and desert, of plains and snowy ranges....How remote and isolated was the ancient land to which we had come!” In 2007, Hollywood director Marc Forster used the city as the stand-in for 1970s Kabul in his film of Khaled Hosseini’s best-selling novel about Afghanistan, The Kite Runner.

The Uighurs have experienced tastes of independence. In 1933, they declared the East Turkestan Republic, from the Tian Shan Mountains south to the Kunlun Mountains, which lasted until a Chinese warlord came to power the next year. Then, in 1944, as the nationalist Chinese government neared collapse during World War II, the Uighurs established the Second East Turkestan Republic, which ended in 1949, after Mao Zedong took over China. Six years after Mao’s victory, China created the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region, similar to a province but with greater local control; the Uighur Muslims are its largest ethnic group.

In the 1990s, the Chinese government built a railway to Kashgar and made cheap land available to Han Chinese, the nation’s majority. Between one million and two million Han settled in Xinjiang during the past two decades, though Kashgar and other towns on the southern edge of the Taklamakan Desert are still predominately Uighur. “Xinjiang has always been a source of anxiety for the central power in Beijing, as is Tibet and Taiwan,” Nicholas Bequelin, a Hong Kong-based Uighur expert at Human Rights Watch told me. “Historically the response to that is to assimilate the territory, particularly through the immigration of Han Chinese.” The Han influx stirs resentment. “All construction and factory jobs around Kashgar have been taken by Han Chinese,” says British journalist Christian Tyler, author of Wild West China: The Taming of Xinjiang. “The people in charge are Han, and they recruit Han. Natural resources—oil and gas, precious metals—are being siphoned off for benefit of the Han.”

Now the Chinese government is doing to Kashgar’s Old City what a succession of conquerors failed to accomplish: leveling it. Early in 2009 the Chinese government announced a $500 million “Kashgar Dangerous House Reform” program: over the next several years, China plans to knock down mosques, markets and centuries-old houses—85 percent of the Old City. Residents will be compensated, then moved—some temporarily, others permanently—to new cookie-cutter, concrete-block buildings now rising elsewhere in the city. In place of the ancient mud-brick houses will come modern apartment blocks and office complexes, some adorned with Islamic-style domes, arches and other flourishes meant to conjure up Kashgar’s glory days. The government plans to keep a small section of the Old City intact, to preserve “a museumized version of a living culture,” says Dru Gladney, director of the Pacific Basin Institute at Pomona College and one of the world’s foremost scholars of Xinjiang and the Uighurs.

The destruction, some say, is business-as-usual for a government that values development over preservation of traditional architecture and culture. In 2005, new construction in Beijing equaled the total in all of Europe, according to the Beijing Cultural Heritage Protection Center (BCHPC), a privately funded advocacy group. In the Chinese capital, one hutong (traditional alley) after another has been demolished in the name of progress. “The destruction of [Kashgar’s] Old City is a bureaucratic reflex, a philistine approach,” says Tyler. “It’s devastating for the history and the culture.”

Others believe the plan reflects a governmental bias against ethnic minorities. “The state does not really see anything of real value in indigenous culture,” says Bequelin. “[The thinking is] it’s good for tourism, but basically [indigenous people] cannot contribute to the modernity of society.” Greed may also be a factor: because most residents of the Old City lack property rights, they can be pushed aside, Bequelin adds, giving developers unbridled opportunity for self-enrichment.

The Chinese government says the demolition is needed to fortify the Old City against earthquakes, the most recent of which struck the region in February 2003, killing 263 people and destroying thousands of buildings. “The entire Kashgar area is in a special area in danger of earthquakes,” Xu Jianrong, Kashgar’s deputy mayor, said recently. “I ask you: What country’s government would not protect its citizens from the dangers of natural disaster?”

But many in Kashgar don’t buy the government’s explanation. They say officials carried out no inspection of the Old City’s houses before condemning them and that most of those that collapsed in recent earthquakes were newly constructed concrete dwellings, not traditional Uighur homes. “These buildings were designed to withstand earthquakes, and used for many centuries,” Hu Xinyu of the BCHPC said of the traditional architecture. He suspects the widespread demolition has a more sinister motive: to deprive the Uighurs of their main symbol of cultural identity. Others view the destruction as punishment for Uighur militancy. The flood of Han Chinese into Xinjiang energized a small Uighur secessionist movement; Uighur attacks against Chinese soldiers and police have occurred sporadically in recent years. The government may well see the Old City as a breeding ground for both Uighur nationalism and violent insurrection. “In their minds, these mazelike alleyways could become a hotbed for terrorist activities,” says Hu.

To halt the destruction, the BCHPC recently petitioned Unesco to add Kashgar to a list of Silk Road landmarks being considered for United Nations World Heritage status, which obliges governments to protect them. China conspicuously left Kashgar off the list of Silk Road sites the government submitted to Unesco. “If nothing is done today,” says Hu, “next year this city will be gone.”

Ling, Mahmati and I had flown southwest to Kashgar from Urumqi, an industrial city of 2.1 million now 80 percent Han Chinese. The China Southern Airways jet had ascended over a sea of cotton and wheat fields at the edge of Urumqi, crossed a rugged zone of crenelated canyons and translucent blue lakes, then soared over the Tian Shan Mountains—a vast, forbidding domain of black basalt peaks, many covered in snow and ice, rising to 20,000 feet—before setting down in Kashgar.

The three of us climbed nervously into a taxi in front of the tiny airport. A government notice posted in the taxi warned passengers to be vigilant against Uighur terrorists. “We should clear our eyes to distinguish between right and wrong,” it advised in both Chinese and the Arabic script of the Uighur language (related to Turkish).

Two months earlier, on July 5, Uighur anger had erupted lethally in Urumqi, when Uighur youths went on a rampage, reportedly stabbing and beating to death 197 people and injuring more than 1,000. (The rioting began as a protest against the killings of two Uighur laborers by fellow Han workers in a southern China toy factory.) Rioting also broke out in Kashgar but was quickly put down. The government blamed the violence on Uighur secessionists and virtually cut off western Xinjiang from the outside world: it shut down the Internet, banned text messages and blocked outgoing international telephone calls.

Just outside the airport, we hit a massive traffic jam: the police had set up a roadblock and were checking identifications and searching every car headed into Kashgar. The tension was even more pronounced as we reached the city center. Truckloads of People’s Liberation Army soldiers rumbled down wide boulevards, past an unsightly mélange of billboards, glass-and-steel banks, the high-rise headquarters of China Telecom and a concrete tower called the Barony Tarim Petroleum Hotel. More troops stood vigilant on sidewalks or ate their lunches in small clusters in People’s Square, a huge plaza dominated by a 50-foot-high statue of Chairman Mao, one of the largest still standing in China.

We pulled into the Hotel Seman, an 1890 relic. Pink-and-green molded ceilings, Ottoman-style arched wall niches and dusty Afghan carpets lining dimly lit hallways evoked a distant era. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Russian consulate was located here, lorded over by diplomat Nicholas Petrovsky, who kept 49 Cossack bodyguards. As Russia tried to extend its influence over the region, Petrovsky and his British counterpart, Consul George Macartney, spent decades spying on each other. When the Chinese revolution that put an end to imperial rule and brought Sun Yat-sen to power reached Kashgar in 1912, violence broke out in the streets. “My one thought was that the children and I must be in clean clothes if we were to be murdered,” Macartney’s wife, Lady Catherine, wrote in her diary. “We all appeared at 4:30 a.m. as though we were going to a garden party, in spotless white!” (The family returned safely to England after departing China in 1918.)

The hotel’s glory days were well behind it. In the dusty and empty lobby, a Uighur clerk in traditional brocade dress and head scarf handed us a blank hotel register—foreign visitors had nearly disappeared since the July violence in Urumqi. At a deserted Internet café, the proprietor reassured us that we were not totally incommunicado. “I have a nephew in Xian,” he said. “I can fax him your message, and then he will send it over the Internet to where you want it to go.”

To tour the back streets of the Old City, Mahmati, Ling and I took a taxi to the Kashgar River, the murky waterway that divides Kashgar, and climbed to a hive of mud-brick buildings hugging a hillside. As the din of the modern city dropped away, we turned a corner and entered a world of monochromatic browns and beiges, gloom and dust, mosques on nearly every corner (162 at last count) and the occasional motor scooter putt-putting though the alleys. A team of Chinese officials carrying briefcases and notepads squeezed past us in one lane. “Are you going out on a tourist excursion?” one of them, a middle-aged woman, asked, and Mahmati and Ling nodded nervously; both surmised the officials were taking a door-to-door survey of the neighborhood’s families in anticipation of evicting them.

In an alley bathed in the perpetual shadow of vaulted archways, we fell into conversation with a man whom I’ll call Abdullah. A handsome figure with an embroidered cap, gray mustache and piercing green eyes, he was standing outside the bright green door to his home, chatting with two neighbors. Abdullah sells mattresses and clothing near the Id -Kah Mosque, the city’s grandest. During the past few years, he told us, he had watched the Chinese government chip away at the Old City—knocking down the ancient 35-foot-high earthen berm that surrounded it, creating wide boulevards through dense warrens of homes, putting up an asphalt plaza in place of a colorful bazaar in front of the mosque. Abdullah’s neighborhood was next. Two months before, officials told residents that they would be relocated in March or April. “The government says the walls are weak, it will not survive an earthquake, but it is absolutely strong enough,” Abdullah told us. “We don’t want to leave, it is history—ancient tradition. But we can’t stop it.”

He led us through the courtyard of his home, filled with drying laundry and potted roses, and up a rickety flight of stairs to a balustraded second-floor landing. I could reach out and practically touch the mottled tan house across the alley. I stood on the wooden balcony and took in the scene: head-scarfed women in a lushly carpeted salon on the ground floor; a group of men huddled behind a half-closed curtain just across the balcony. The men were Abdullah’s neighbors who had gathered to discuss the eviction. “We don’t know where we’re going to be moved to, we have no idea,” one of them told me. “Nobody here wants to move.”

Another man weighed in: “They say they are going to rebuild the place better. Who designs it? Nothing is clear.”

Abdullah said he was told that homeowners would be able to redesign their own dwellings and the government would pay 40 percent. But one of his neighbors shook his head. “It has never happened before in China,” he said.

One evening, Mahmati took me to a popular Uighur restaurant in Kashgar. Behind closed doors in a private room, he introduced me to several of his friends—Uighur men in their mid-20s. As a group they were angry about tight surveillance by Chinese security forces and inequalities in education, jobs and land distribution. “We have no power. We have no rights,” a man I’ll call Obul told me over a dinner of lamb kebabs and cabbage dumplings.

In 1997, Chinese troops in the Xinjiang town of Ghulja fired on protesting Uighur students waving the flags of East Turkestan, killing an unknown number. Then, following the 9/11 attacks, the Chinese persuaded the United States to list a secessionist group calling itself the East Turkestan Islamic Movement as a terrorist organization, claiming it had ties to Al Qaeda.

During the American-led offensive against the Taliban in Afghanistan in 2001, Pakistani bounty hunters captured 22 Uighurs on the Afghan-Pakistan border. The prisoners were turned over to the U.S. military, which incarcerated them at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. The Bush administration eventually released five to Albania and four to Bermuda. Six were granted asylum on the South Pacific island of Palau this past October. Seven Uighurs remain at Guantanamo, with ongoing litigation about whether they can be released in this country. (The federal government has determined that they pose no threat to the United States.) The Supreme Court has agreed to take up the case.

Just before the 2008 Beijing Olympics, the Chinese government claims, two Uighurs driving a truck deliberately slammed into a column of Chinese paramilitary police jogging through the streets of Kashgar, killing 16 of them. (Eyewitness accounts from foreign tourists cast doubt on whether this was intentional.) In the following days, a few explosives went off 460 miles south of Urumqi, in the city of Kuqa, presumably the work of Uighur nationalists. But, says Bequelin of Human Rights Watch, “these are small groups with no coordination, no international support. They have no access to weapons, no training.” The Chinese cracked down on all Uighurs, shuttering Islamic schools and tightening security.

One of the men at dinner that night told me that after he went to Mecca for the hajj, the annual holy pilgrimage, in 2006, he was interrogated by Chinese intelligence agents and ordered to surrender his passport. “If you are a Uighur and you need a passport for business purposes, you must pay 50,000 yuan (about $7,500),” another dinner guest told me. Ling suggested that the Uighurs were partly to blame for their problems, saying they didn’t value education and their children had suffered for it. Obul acknowledged the point, but said it was too late for reconciliation with the Han majority and the Chinese government. “For us,” he said, “the most important word is ‘independence.’”

It didn’t take long before I—as one of the few foreigners then visiting Kashgar—came to the attention of Chinese authorities. At about 9 p.m. on my second night in Kashgar, there was a knock on my hotel room door. I opened it to confront two uniformed Han police officers, accompanied by the hotel manager. “Let me see your passport,” one officer said in English. He rifled through the pages.

“Your camera,” he said.

I retrieved it from my knapsack and displayed the digital photographs one by one—scenes from the Sunday animal market, where Uighurs from rural Xinjiang meet to buy and sell donkeys, sheep, camels and goats; shots taken in the alleys of the Old City. Then I came to a picture of a half-collapsed house, mud walls sagging, tile roof disintegrating—belying the image of burgeoning prosperity that China projects to the world.

“Remove the picture,” a police officer commanded.

“Excuse me?”

He tapped his finger on the screen.

“Remove it.”

Shrugging, I deleted the photo.

Mahmati, meanwhile, had been taken to the first floor of the hotel for interrogation. At midnight, he called me on his cellphone to say, in a quavering voice, that he was being taken to Kashgar’s security headquarters.

“It’s because he is a Uighur,” Ling said bitterly. “The Chinese single them out for special treatment.”

It was long past midnight when Mahmati returned. The police had questioned him for two hours about his relationship with Ling and me and had asked him to account for all the time we had spent together. Then they made Mahmati provide names, addresses and phone numbers for every member of his family in Kashgar, and warned him not to enter the “forbidden area” again—apparently the part of the Old City not designated a tourist zone. “They demanded to know the real reason for our journey. But I didn’t tell them anything,” he said.

On one of our last days in Kashgar, Mahmati, Ling and I took a government-licensed tour through a tiny section of the Old City—about 10 percent of it—for 30 yuan (about $4.40). Here was a glimpse of the sanitized future that the Chinese government apparently envisions: a Uighur woman clad in a green vest and long blue skirt led us past reconstructed houses adorned with clean ceramic tiles, handicraft shops and cafés offering Western-style food—a tidy, highly commercialized version of the Old City. She kept up a cheerful patter about the “warm relations” among “all of China’s peoples.”

But under Mahmati’s gentle questioning, our guide began to express less charitable feelings toward the Chinese government. It had refused to allow her to wear a head covering on the job, she said, and had denied her permission to take breaks for prayer. I asked her whether the area we were walking through would be spared the wrecking ball. She looked at me and paused before answering. “If the customer asks, we are supposed to say it will not be destroyed,” she finally answered, “but they will destroy it with everything else.” For a moment she let her anger show. Then she composed herself and said goodbye. We left her standing on the street, below a banner that declared, in English: “Ancient residence, a slice of the real Kashgar.”

Writer Joshua Hammer lives in Berlin. Michael Christopher Brown travels the world on assignment.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)