Digging Up the Past at a Richmond Jail

The excavation of a notorious jail recalls Virginia’s leading role in the slave trade

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/excavation-jail-cell-Richmond-Virginia-631.jpg)

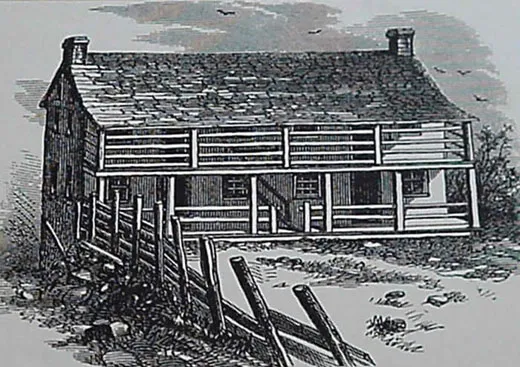

Archaeologists knew that Robert Lumpkin's slave jail stood in one of the lowest parts of Richmond, Virginia—a sunken spot known as Shockoe Bottom. From the 1830s to the Civil War, when Richmond was the largest American slave-trading hub outside of New Orleans, "the devil's half acre," as Lumpkin's complex was called, sat amid a swampy cluster of tobacco warehouses, gallows and African-American cemeteries. This winter, after five months of digging, researchers uncovered the foundation of the two-and-a-half-story brick building where hundreds of people were confined and tortured. Buried under nearly 14 feet of earth, the city's most notorious slave jail was down a hill some eight feet below the rest of Lumpkin's complex—the lowest of the low.

"People inside would have felt hemmed in, trapped," says Matthew Laird, whose firm, the James River Institute for Archaeology Inc., uncovered the 80- by 160-foot plot. On a wet December day, the site was a deep, raw pit pocked with mud puddles, with an old brick retaining wall that divided the bottom—which soaked workers were struggling to pump dry—into two distinct tiers.

A century and a half ago, there would have been plenty of traffic back and forth between the upper level of the complex, where the master lived and entertained guests, and the lower, where slaves waited to be sold. Lumpkin, a "bully trader" known as a man with a flair for cruelty, fathered five children with a black woman named Mary, who was a former slave and who eventually acted as his wife and took his name. Mary had at least some contact with the unfortunates her husband kept in chains, on one occasion smuggling a hymnal into the prison for an escaped slave named Anthony Burns.

"Imagine the pressure that was applied, and what she had to live through," says Delores McQuinn, chairwoman of Richmond's Slave Trail Commission, which promotes awareness of the city's antebellum past and sponsored much of the dig.

Though Lumpkin's jail stood only three blocks from where the state capitol building is today, except for local history buffs "no one had a clue that this was here," McQuinn says. Razed in the 1870s or '80s, the jail and Lumpkin's other buildings were long buried beneath a parking lot for university students, part of it lost forever under a roaring strip of Interstate 95. Preservation efforts didn't coalesce until 2005, when plans for a new baseball stadium threatened the site, which archaeologists had pinpointed using historical maps.

The place has haunted McQuinn ever since her initial visit in 2003, soon after she first learned of its existence. "I started weeping and couldn't stop. There was a presence here. I felt a bond," she said. "It's a heaviness that I've felt over and over again."

Digging from August to December in "this place of sighs," as James B. Simmons, an abolitionist minister, called the jail in 1895, Laird and his team found evidence of a kitchen and cobblestone courtyard on the upper level of Lumpkin's property, but didn't verify finding the jail itself until the last weeks of work. Even then they couldn't do much more than mark the spot, because groundwater from a nearby creek filled up trenches almost as fast as they could be dug. Decades of dampness had its advantages, though. Because oxygen does not penetrate wet soil, the bacteria that typically break down organic matter don't survive. As a result, many details of daily life were preserved: wooden toothbrushes, leather shoes and fabric.

The archaeologists found no whipping rings, iron bars or other harsh artifacts of slavery, but there were traces of the variety of lives within the compound. Shards of tableware included both fine hand-painted English china and coarse earthenware. Parts of a child's doll were also recovered on the site, a hint of playtime in a place where some people were starved into submission. To whom did the doll belong? Did its owner also belong to someone?

"Robert Lumpkin came out of nowhere," says Philip Schwarz, a professor emeritus of history at Virginia Commonwealth University who has researched the Lumpkin family for years. Lumpkin began his career as an itinerant businessman, traveling through the South and buying unwanted slaves before purchasing an existing jail compound in Richmond in the 1840s.With a designated "whipping room," where slaves were stretched out on the floor and flogged, the jail functioned as a human clearinghouse and as a purgatory for the rebellious.

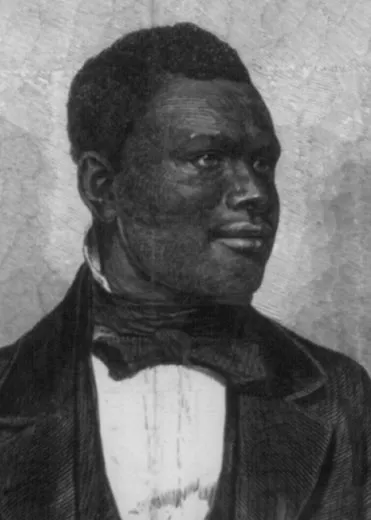

Burns, the escaped slave who, after fleeing Virginia, was recaptured in Boston and returned to Richmond under the Fugitive Slave Act, was confined in Lumpkin's jail for four months in 1854, until Northern abolitionists purchased his freedom. According to an account Burns gave his biographer, Charles Emery Stevens, the slave was isolated in a room "only six or eight feet square," on a top floor accessible by trapdoor. Most of the time he was kept handcuffed and fettered, causing "his feet to swell enormously....The fetters also prevented him from removing his clothing by day or night, and no one came to help him....His room became more foul and noisome than the hovel of a brute; loathsome creeping things multiplied and rioted in the filth." He was fed "putrid meat" and given little water and soon fell seriously ill. Through the cracks in the floor he observed a female slave stripped naked for a potential buyer.

Meanwhile, Lumpkin sent two of his mixed-race daughters to finishing school in Massachusetts. According to Charles Henry Corey, a former Union army chaplain, Lumpkin later sent the girls and their mother to live in the free state of Pennsylvania, concerned that a "financial contingency might arise when these, his own beautiful daughters, might be sold into slavery to pay his debts."

"He was both an evil man and a family man," Schwarz says.

Lumpkin was in Richmond in April 1865 when the city fell to Union soldiers. Shackling some 50 enslaved and weeping men, women and children together, the trader tried to board a train heading south, but there was no room. He died not long after the war ended. In his will, Lumpkin described Mary only as a person "who resides with me." Nonetheless he left her all his real estate.

In 1867, a Baptist minister named Nathaniel Colver was looking for a space for the black seminary he hoped to start. After a day of prayer, he set out into the city's streets, where he met Mary in a group of "colored people," recalling her as a "large, fair-faced freedwoman, nearly white, who said that she had a place which she thought I could have." After the bars were torn out of the windows, Mary leased Lumpkin's jail as the site of the school that became Virginia Union University, now on Lombardy Street in Richmond.

"The old slave pen was no longer 'the devil's half acre' but God's half acre," Simmons wrote.

Mary Lumpkin went on to run a restaurant in Louisiana with one of her daughters. She died in New Richmond, Ohio, in 1905 at 72.

McQuinn, who is also a minister, hopes the site will one day become a museum. Though it has been reburied for the time being, she says it will never again be forgotten: "The sweetest part," she says, "is now we have a story to tell."

Abigail Tucker is Smithsonian's staff writer.