With the Discovery of the USS Conestoga, Researchers Have Solved a Mystery That Was Nearly 100 Years Old

Even a century later, the news has brought relief to the families of the sailors who went down with their ship

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c7/e7/c7e7373b-a0da-4ea9-8ac3-ab87473a067d/conestoga_at_54_at_san_diego_circa_january_1921_naval_historical_center_photograph_nh_71299.jpg)

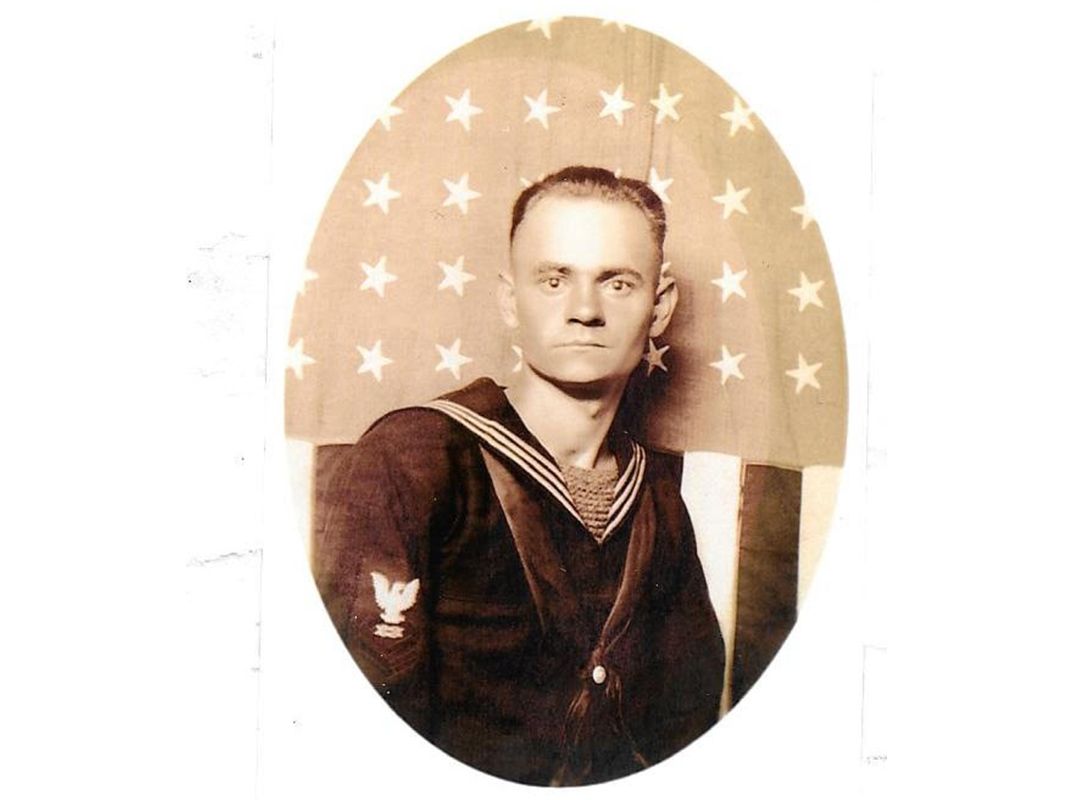

Harvey Reinbold had just gotten married the year before, and he was hoping to retire from the Navy to settle down with his new wife.

Ernest Larkin Jones had a three-year-old daughter who traveled all the way from Rhode Island to California with her mother just to see her father’s ship leave port.

George Kaler had just joined the Navy a few years earlier, during World War I, and he was eager to explore the world beyond his tiny Ohio hometown.

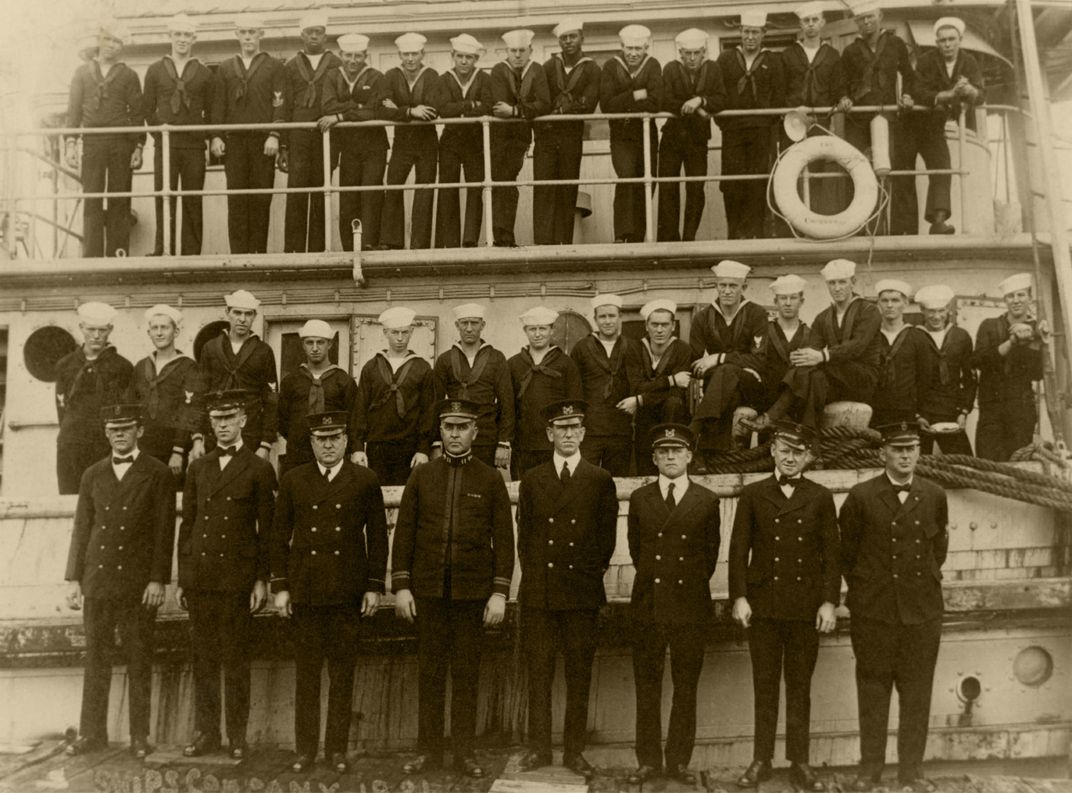

All were among 56 men who vanished in 1921 aboard the U.S.S. Conestoga, a long-lost tugboat that has finally been found—nearly a century after its disappearance. The discovery of the shipwreck off the coast of San Francisco has solved one of the greatest maritime mysteries in the Navy’s history, as neither the fate of the ship nor its crewmembers had been known until now.

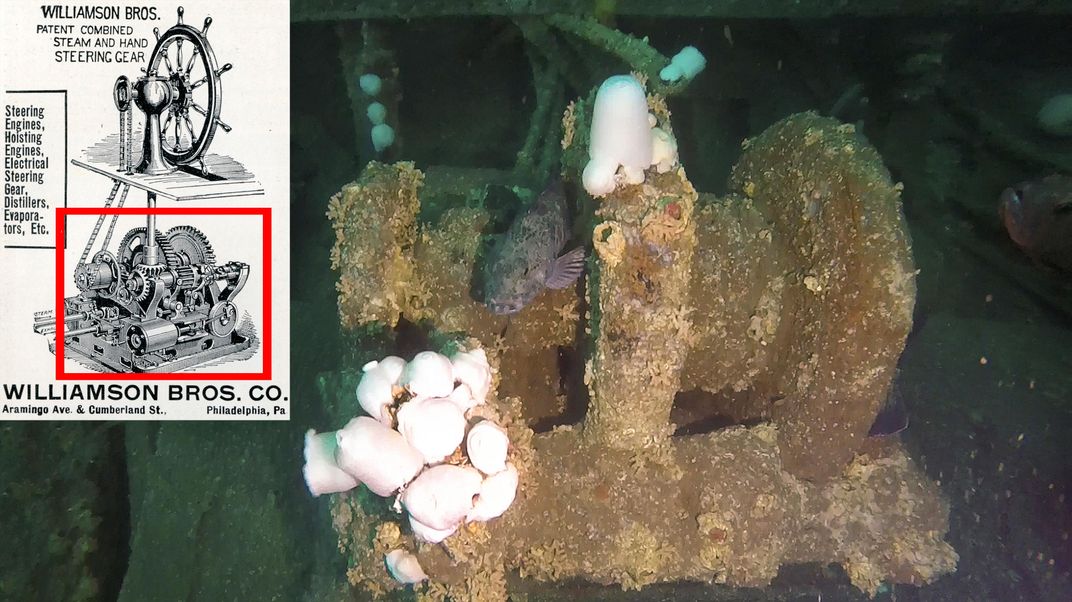

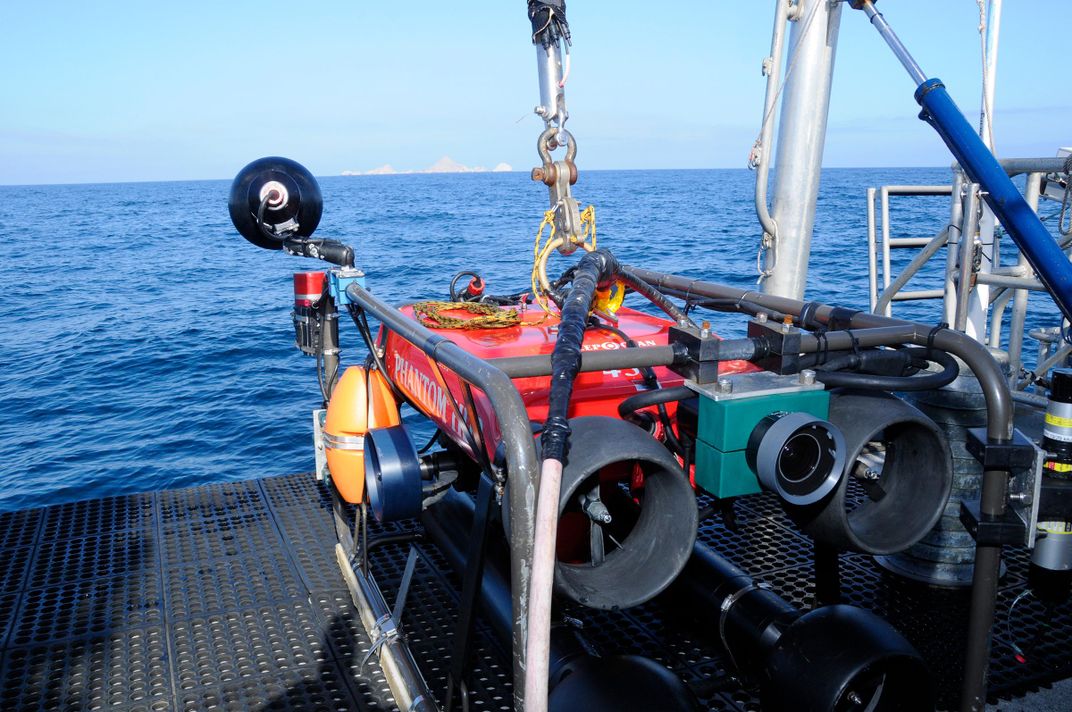

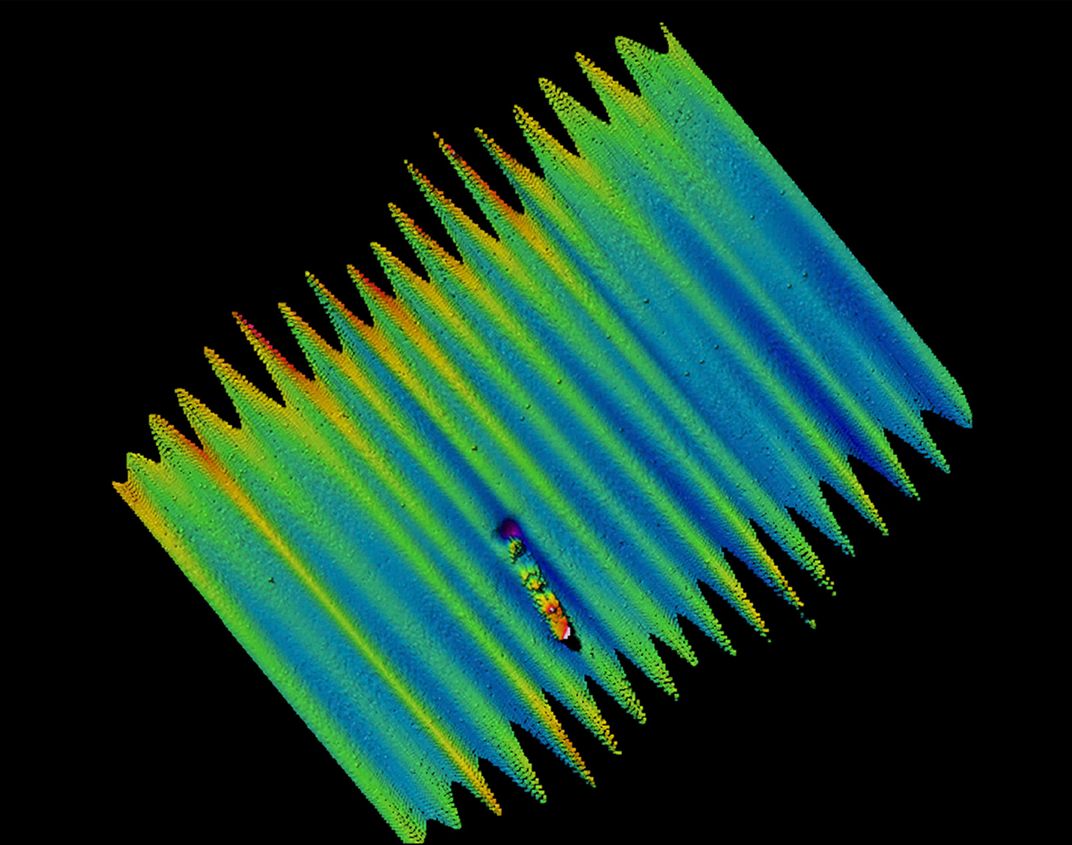

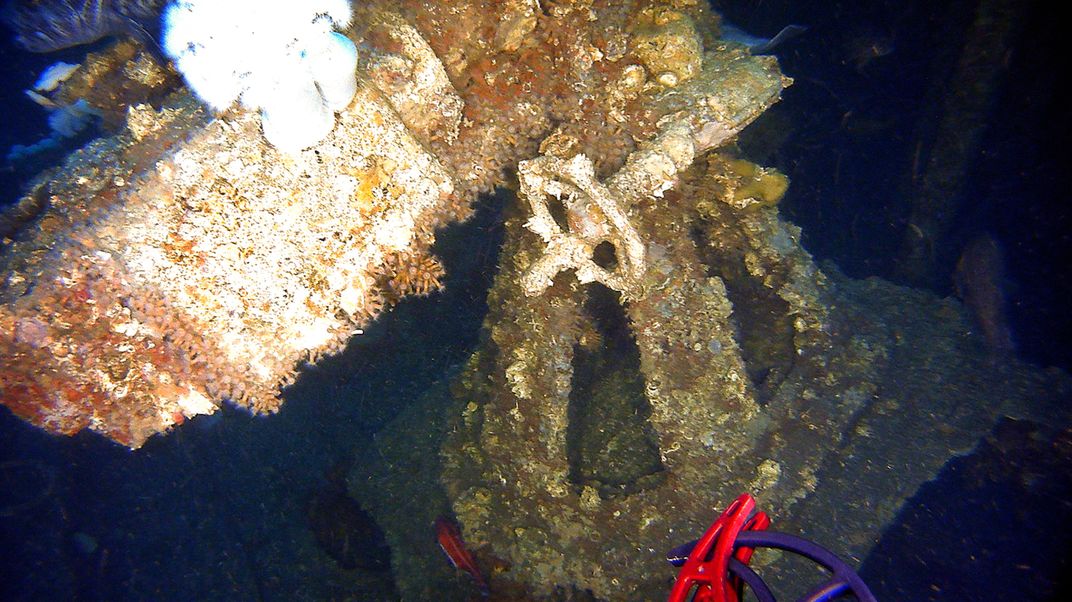

NOAA discovered remains of the tugboat about 2,000 miles away from where it was originally presumed to have been lost, in California’s Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary. The Conestoga first appeared in 2009 on a sonar survey that the agency was conducting to document historical shipwrecks in the San Francisco area. At the time, investigators weren’t even sure a wreck was there. Conducting dives in 2014 and 2015, investigators used video cameras mounted on remote-operated vehicles to examine the underwater site more closely. “We went back three times because it just kept calling to us,” says James Delgado, director of NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries’ Maritime Heritage Program. “There was something about it that spoke to mystery.”

Delgado and Robert Schwemmer, the office’s West Coast regional coordinator, first suspected that the ship might be the Conestoga in the fall of 2014 and confirmed its identity during their October 2015 expedition.

News of the discovery—which NOAA and the Navy officially announced on Wednesday—has shocked the relatives of the Conestoga’s crewmembers, whose families had spent their lives wondering what had happened to their loved ones. “I looked up in heaven and said, ‘Daddy—they found your dad,’” says Debra Grandstaff, whose grandfather, William Walter Johnson, had been the ship’s barber.

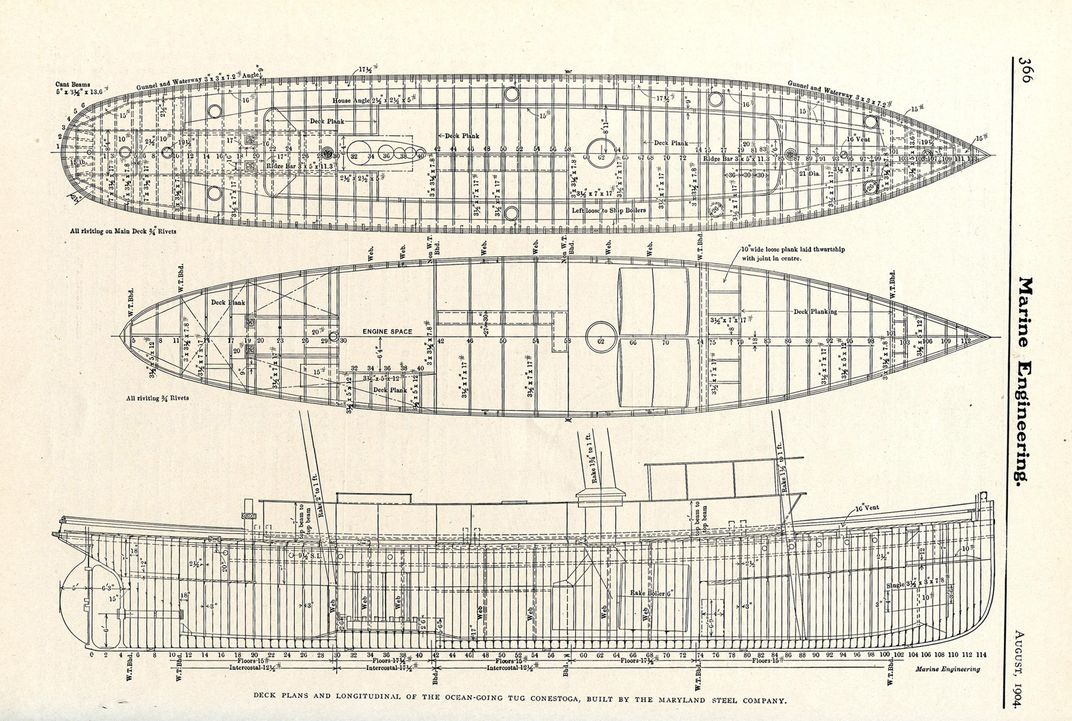

The Conestoga was last seen on March 25, 1921, when it departed from Mare Island, just north of San Francisco, bound for American Samoa to serve as a station ship. Originally built to tow coal barges, the Conestoga escorted convoys and transported supplies during World War I, and it appears to have been towing a barge that was lost before the ship sunk, An older ship, the tugboat needed repairs to its bilge pumps—a problem that may have ultimately contributed to its demise. A mistaken report out of Pearl Harbor that the vessel had arrived there as planned meant that it took weeks before anyone had even realized the Conestoga was missing.

After the Navy realized that the Conestoga had not, in fact, arrived in Oahu, the military focused its search for the missing ship around the Hawaiian Islands, ultimately deploying about 60 vessels—“including the entire destroyer fleet at Pearl Harbor and submarines”—as well as scores of aircraft, according to a report co-authored by Delgado and Schwemmer

It was “an age prior to vessel tracking, and no one having responsibility for determining if and when the ship arrived in Pearl Harbor,” says Delgado. The Navy only belatedly realized that the ship was overdue and by then, it was looking “2,000 miles too far.”

At the time of the ship’s disappearance, there was a smattering of evidence that it had sunk closer to the Bay Area: A lifejacket labeled “U.S.S. Conestoga” washed up on a beach about 30 miles south of San Francisco, along with some boxes and kegs. But the Navy dismissed the potential clues, concluding that the life preserver might have been lost overboard before the ship had even departed from Mare Island. The Navy also examined a bronze letter “C” that had been affixed to a lifeboat found some 650 miles west of Manzanillo, Mexico. But it was a baffling clue that appeared thousands of miles from both Conestoga’s place of departure and its destination. The lifeboat was “battered and barnacle covered, showing it was out at sea for a while,” says Delgado. “There was no definitive ‘smoking gun’ saying it was Conestoga’s boat.”

On June 30, 1921, the Navy officially declared that USS Conestoga was lost at sea with all hands. But for years, the “mystery ship” remained an object of fascination for the broader public, which speculated that the Conestoga had been “the victims of pirates, mutineers, [or] renegade Bolsheviks” heading for Siberia’s gold fields, according to NOAA’s report.

In 1958, retired naval officer Robert Myers wrote a letter about the missing ship to All Hands magazine, an official Navy publication. “Mystery, profound and complete, which surrounds the disappearance of ships at sea, continues to capture the imagination and interest of mortal man,” he wrote. The magazine’s editors then challenged its readers to solve the puzzle of the Conestoga’s “voyage into nothingness” for themselves: “Did she capsize? Did one of her tows spring a leak and drag her under? You figure it out—if you can.” But no one could.

Diane Gollnitz, the granddaughter of Jones, the ship’s commanding officer, remembers the anguish that gripped her family for decades afterwards. Her mother tried in vain to recall anything about her own father, but she was only been a toddler when she saw him off and couldn’t remember a thing. Jones’s mother, meanwhile, was convinced for years that her son was marooned “on an island in the Pacific somewhere,” Gollnitz continued. But that hope faded as time passed, and there was still no sign of the men or the ship. “It was a void, it was just an emptiness— it’s the not knowing, you can’t bring that to closure,” says Gollnitz.

The missing ship left William Walter Johnson’s wife to raise three children on her own. Before his final voyage, he had taught her how to cut hair, and she worked as a hairdresser throughout the 1920s and the Great Depression to support her family. Linda Hosack, Johnson’s granddaughter, recalled visiting Arlington Cemetery’s Tomb of the Unknown Soldier to pay respects with her mother, Johnson’s daughter. “My mother always said that was him,” Hosack says.

The missing ship would haunt George Kaler’s mother, Annie, for the rest of her life. His cousin Peter Hess believes that the unanswered questions about the crew’s fate made it far more difficult for her to come to grips with the loss of her son. Kaler’s parents bought three burial chambers in their hometown cemetery for the family, and they never resold the one meant for their son, which marked with a plaque bearing his name.

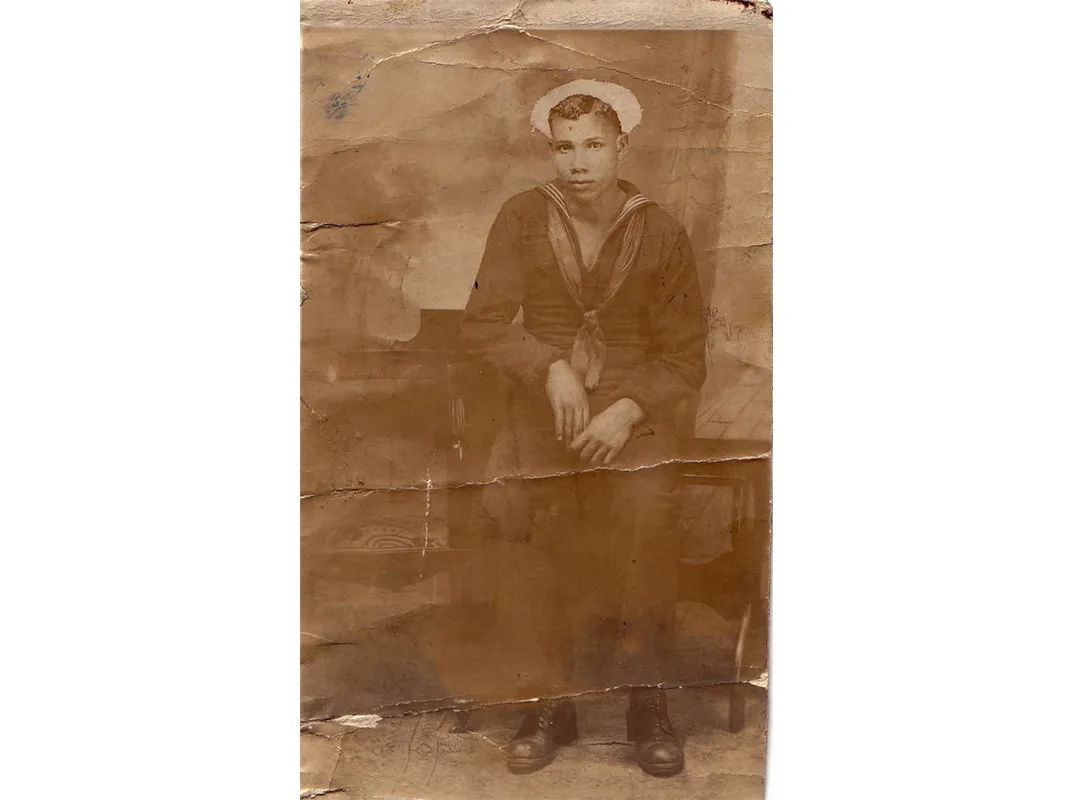

“It was always there, in the back of our minds: ‘Where is he? Why can’t he been found?’ says Violet Pammer, recalling the photo of Reinbold, her great uncle who was the Conestoga’s executive offer, that always hung in the family's living room. When she received the news that Conestoga had been discovered, she was floored. Months later, she still can’t talk about it without getting a shiver down her spine. “It gives me the chills—the goose bumps,” she says.

NOAA confirmed the identity of the shipwreck after its October 2015 expedition, but Delgado and Schwemmer were adamant about contacting as many family members as possible before going public with the news about the ship’s discovery. They wanted to inform the families personally about what had happened before they heard it on the news. “I've put down the phone and cried as they’ve cried—it may be 95 years, but for some of these families it’s not that long.” The team worked with a genealogist to track down the crew’s family members and descendants and have successfully located relatives of about half of the families so far. Their outreach to family members is ongoing, and they hope the announcement of the discovery will help them connect with other relatives as well.

Video footage shows that the wreck is largely intact, including a 3-inch, 50-caliber gun mounted on the main deck that was critical to confirming the identity of the Naval tugboat, which the Navy had originally purchased to use during World War I. The metal hull has become a reef of sorts for marine life in the sanctuary, covered in white plume anemones and surrounded by yellow-orange rockfish.

NOAA believes the location of the shipwreck helps explains why the Conestoga had sunk in the first place. On the day of its departure, winds had sped up from 23 miles per hour to 40 miles per hour, with increasingly rough seas. Investigators suspect that the ship was “leaking from the strain of laboring in heavy swell, and shipping water seas that over-washed the decks, with water overwhelming the bilge pumps” before it suddenly overcome. A muddled radio transmission later broadcast by another ship said the Conestoga was “battling a storm and that the barge she was towing had been torn adrift by heavy seas,” according to NOAA’s report. The San Francisco Chronicle reported the clue in May 1921, suggesting that the distress call was issued around the time of the Conestoga’s departure. But it, too, was disregarded as there were conflicting reports about the date and origin of the message’s transmission.

In light of the wreck’s discovery, NOAA now believes that it was indeed a distress call from the Conestoga. “In remembering the loss of the Conestoga, we pay tribute to her crew and their families, and remember that, even in peacetime, the sea is an unforgiving environment,” Dennis McGinn, assistant secretary of the Navy, said in a statement.

Judging by the ship’s north/northwest direction and position, investigators believe that the Conestoga was seeking shelter from the bad weather by heading towards a cove on Southeast Farallon Island, about three miles from the site of the wreck. “This would have been a desperate act, as the approach is difficult and the area was the setting for five shipwrecks between 1858 and 1907,” Delgado and Schwemmer wrote. “However, as Conestoga was in trouble and filling with water, it seemingly was the only choice to make.”

The dives revealed no human remains, and there will be no plans to resurface the Conestoga. Like other shipwrecks, the tugboat is protected by a law that prohibits “unauthorized disturbance” of sunken military craft owned by the U.S. government. “This is a military gravesite, and we want to have it protected,” said Schwemmer.

Grandstaff only just wishes that her father, who died in 2007, had been alive to receive the news. Though he never knew his own father, Grandstaff's father joined the Navy as well to follow in Johnson’s footsteps, ultimately becoming a World War II veteran who served for more than 20 years. “Now my dad can rest in peace. Now I can rest in peace, knowing that I really did have a grandfather,” she said. “A book has been closed now.”