Women of the Early 1900s Rallied Behind Beautiful, Wartless Witches

Women looking to work, vote and marry whomever they wanted turned the Halloween icon into a powerful symbol

Not unlike today, women's magazines in the early 20th century dictated how Halloween should be celebrated. They showed what decorations you ought to have and how to throw a memorable party. But the holiday itself was very different. There was no trick-or-treating and decidedly less fright and gore.

"It is not meant to be super scary," says Daniel Gifford. "It is meant to be a party for women in which they think about courtship, love and romance. They invite mixed-sex crowds to these parties so they can do things like bob for apples, where faces come very close to each other."

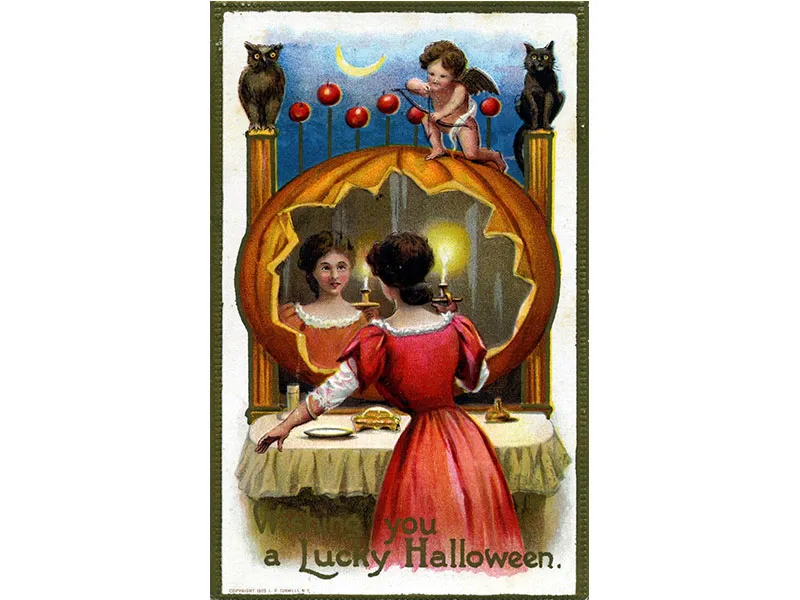

In fact, while goblins and bats figure in to popular depictions, so does Cupid.

Gifford works at the National Museum of American History and is an expert on American holidays. He has collected and studied hundreds of postcards that circulated among women at this time, and, when it comes to the Halloween-themed ones, he is particularly interested in illustrations of witches.

For centuries, the archetype of the hag with a hooked nose, warts, scraggly hair and a cauldron has pervaded art and literature. Think of the witches in Shakespeare's Macbeth with their bubbling "eye of newt, and toe of frog" potion and the villains the Brothers Grimm created in "Snow White," "Hansel and Gretel" and "Sleeping Beauty." But, Gifford has found that artists, between 1905 and 1915, tended to portray witches as beautiful sorceresses with blushed cheeks and ample curves.

"To our eyes, these look very tame. They are not what we would call super sexy by today’s standards," says Gifford. "But in the context of the day, while I wouldn’t go as far as to say there are erotic elements, they certainly show off these women’s best features."

Here, below, is a postcard from Gifford's personal collection that exemplifies this early 20th-century trend. Click on the pins to learn more about the image.

The scholar of holidays has his own theory as to why this trope was so appealing. Rather then writing them off as superficial, Gifford sees these beautiful witches—images that were passed from woman to woman—as part of a shrewd power play, considering the historical context.

"This is the period of the New Woman—the woman who wants to have her say, to be able to work, marry who she chooses, to divoce, and, of course, to be able to vote," Gifford explains. "There are lots of questions about how much power women have at this time. What sort of boundaries can they push? How far can they push them? What sense of control do they have over their own lives and their own fate?"

Witches, traditionally, were seen as having lots of power, and perhaps women wanted to subsume some of that without seeming ugly for doing so.

Daniel Gifford will discuss this image and others at tonight's Smithsonian Associates lecture, "Halloween Changes Its Disguise: Has the Witching Season Grown Up?"

American Holiday Postcards, 1905-1915: Imagery and Context

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)