John Glenn and the Sexism of the Early Space Program

Fan mail sent to the astronaut reveals the rigidity of gender roles in the 1960s

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8b/3d/8b3d35f4-db52-47ea-b75e-793ca6ba80cb/image-20161212-31402-1h3qx45.jpeg)

News of the death of John Glenn – “the last genuine American hero” – ricocheted across the internet on Dec. 8, 2016, in less time than it had taken the famed astronaut to complete his first Earth orbit.

NASA, the U.S. Marine Corps, President Barack Obama and many others quickly posted laudatory tributes on social media. In the first 48 hours after it was published, The New York Times’ obituary garnered more than 500 online comments from readers sharing their sentiments and personal memories, many laced with nostalgia.

One commenter, “Mom,” wrote about being a fifth grader, listening at school to a transistor radio on the morning of John Glenn’s flight. “This was the definition of the future,” Mom wrote. “I wanted to do hard math with slide rules and learn hard languages and solve mysteries. I wanted to be like John Glenn.”

But was the pioneering starman really everybody’s hero?

At least in the early days after his flight, the relationship between John Glenn and his young female fans was complicated by the male-dominated cultures of 1960s America and the U.S. space program. Prevailing gender role stereotypes, limited opportunities, sexism and a lack of female role models in the world of science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) all stood between girls’ dreams and the stars.

‘Even though I am a girl…’

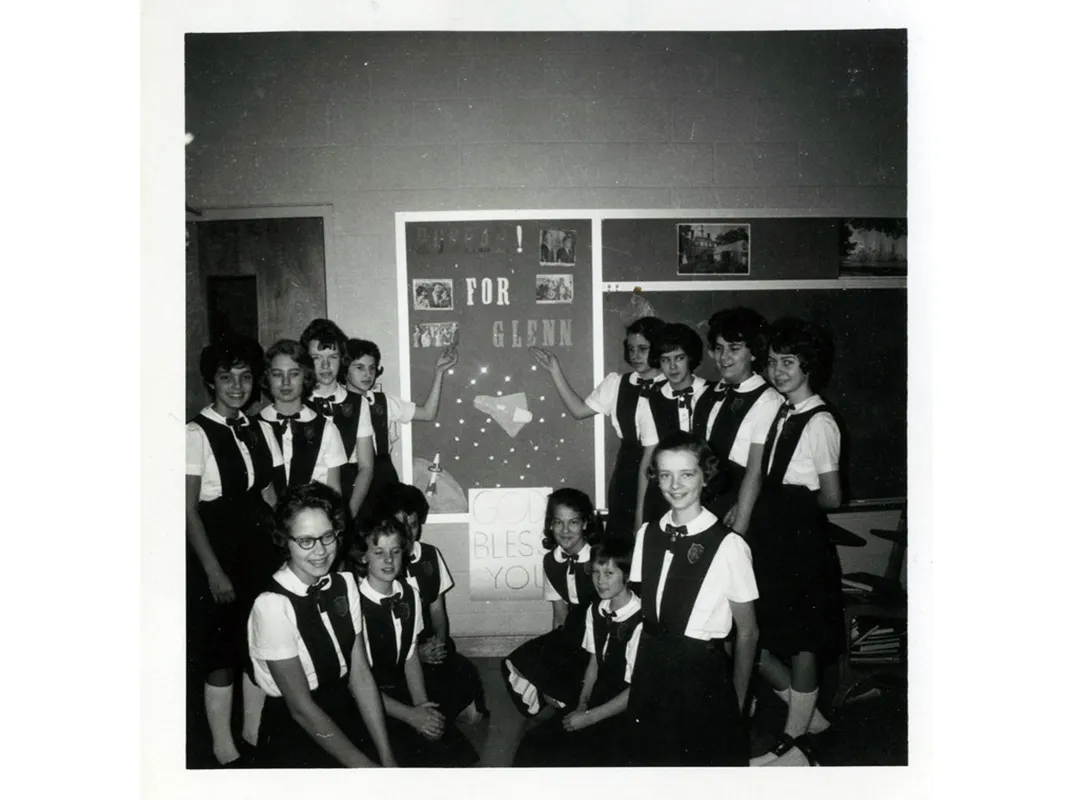

Recollections of Glenn are of particular interest to me as a historian undertaking a major research project called “A Sky Full of Stars: Girls and Space-Age Cultures in Cold War America and the Soviet Union.” At the heart of the study is my analysis of hundreds of fan mail letters written by girls in the U.S. and USSR to three pioneers of human space flight – Yuri Gagarin, John Glenn and Valentina Tereshkova – whose respective orbital voyages around the Earth in 1961, 1962 and 1963 unleashed the imaginations of a generation of children swept up in the “space craze.”

I set out to discover how girls in both countries understood their life possibilities at the dawn of the space age and how science and technology fit into their equations.

Based on my research in the John H. Glenn Archives at Ohio State University, the majority of American girls’ letters to Glenn conformed to established gender conventions. Girls frequently congratulated the astronaut on stereotypically masculine characteristics – strength and bravery – while denying that they themselves possessed those qualities. Some were openly flirtatious, offering admiring personal comments on Glenn’s appearance, physique and sex appeal. Some also wrote to request an autograph or glossy photo, embracing a well-established culture of celebrity and fandom that was pervasive among American girls of the era.

The letters that interest me most are from girls who were so inspired by Glenn’s accomplishment that they envisioned for themselves a place in the STEM sphere. Some wrote to Glenn to report about their science fair projects or rocket design clubs and to ask for technical advice. Some expressed the desire to follow their hero into careers in aviation and astronautics, even as they expressed skepticism that such a path would be open to them.

The formulation “even though I am a girl I hope to be just like you” in various manifestations appeared as a steady refrain in girls’ letters. Diane A. of Fergus Falls, Minnesota, wrote, “I would very much like to become an astronaut, but since I am a 15-year-old girl I guess that would be impossible.” Suzanne K. from Fairfax, Virginia, was more defiant: “I hope I go to the moon sometime when I’m older. I’m a girl but if men can go in space so can women.” Carol C. of Glendale, New York, wrote to ask “this one simple question concerning a woman’s place in space. Will she only be needed around Cape Canaveral or will she eventually accompany an astronaut into space? If so I sure wish I were she.”

The news that “the Russians” had sent a woman into space in June 1963 emboldened some girls to ask Glenn more pointed questions. Ella H. of Meridian, Mississippi, wrote on behalf of her junior high school class to inquire, “What were our male astronauts’ reactions when Russia’s female astronaut made more orbits than they? …Do you seven male astronauts think that a women will go into space within the next two years?” Meanwhile, Patricia A. of Newport News, Virginia, asked Glenn outright, “Do you think that sending women into space is a very good idea?”

Glenn and the ‘problem’ of ‘lady astronauts’

While few of his replies to letter writers were preserved in the archive, those that exist suggest Glenn avoided encouraging girls’ dreams of flight and space exploration.

Fourteen-year-old Carol S. in Brooklyn wrote to her “idol” to share her “strong desire to be an astronaut” and seek Glenn’s advice on how to overcome the obstacle of being a girl, “a slight problem it seems.” Glenn replied four months later to thank Carol for her letter, but rather than answering her query directly he enclosed “some literature which I hope will answer your questions.”

A girl named “Pudge” from Springfield, Illinois sent a long enthusiastic letter sharing her plans to join the Air Force and her “thrill at the sight or sound of jets, helicopters (especially the H-37A ‘Mojave’) rockets or anything connected with space, the Air Force or flying.” Glenn sent a friendly reply including “some literature about the space program which I hope you will enjoy,” but said nothing about the viability of the girl’s aspirations.

Hard evidence of Glenn’s position on the question of “lady astronauts” came in the form of his congressional testimony in July 1962. A Special Subcommittee on the Selection of Astronauts of the House Committee on Science and Astronautics was formed in response to the quashing of the privately funded “woman in space” program and related allegations of sexual discrimination at NASA.

A March 1962 letter from the director of NASA’s Office of Public Services and Information to a young girl who had written to President John F. Kennedy to ask if she could become an astronaut stated that “we have no present plans to employ women on space flights because of the degree of scientific and flight training, and the physical characteristics, which are required.”

Glenn’s testimony before the subcommittee echoed that position. In his opinion, the best-qualified astronauts were those who had experience as military pilots, a career path that was closed to women. In a much-quoted statement, Glenn asserted that “the men go off and fight the wars and fly the airplanes and come back and help design and build and test them. The fact that women are not in this field is a fact of our social order.” The subcommittee’s final report concurred, effectively barring female applicants from consideration for the Apollo missions.

Crucially, Glenn’s position soon evolved in a more egalitarian direction. As historian Amy E. Foster noted, a May 1965 Miami Herald article headlined “Glenn Sees Place for Girls In Space” quoted the astronaut as saying that NASA’s plans to develop a new “scientist-astronaut” program should “offer a serious chance for space women.”

Not looking like John Glenn

While much of the commentary about Glenn since his death has been highly celebratory, a subtle line of critique has reawakened questions about the ways in which gender, race, ethnicity and class have been inscribed in the history of America’s space program. A woman identified as “Hope” was the lone voice in The New York Times comments to urge people to remember that the first astronauts “knew they were there because they were men, and were white, and were chosen above others who may have been just as fit but didn’t look like John Glenn.”

In fact, Glenn’s death has helped bring welcome attention to the accomplishments of some of the U.S. space program’s unsung heroes, individuals who did not look like the famed astronaut but who helped make his voyage possible. Mentions of the much-anticipated feature film Hidden Figures, set for debut in early January, are especially noticeable.

Meet the remarkable African American Women of @nasa who made John Glenn's inaugural orbit around Earth possible https://t.co/MLmo0toeoG pic.twitter.com/NnWacIujts

— Clarke Center (@imagineUCSD) December 8, 2016

The movie focuses on Katherine Johnson, Mary Jackson and Dorothy Vaughn – three African-American women of NASA who helped make John Glenn’s flight around the Earth possible. As writer and social critic Rebecca Carroll put it in a tweet, Glenn became “the first American to orbit the earth bc he trusted a black woman to do the math.” As of this writing, it was retweeted more than any other #johnglenn item in recent days.

RIP #johnglenn. The first American to orbit the earth bc he trusted a black woman to do the math. #KatherineJohnson @HiddenFigures

— Rebecca Carroll (@rebel19) December 8, 2016

President Obama wrote in his statement on Glenn’s death that “John always had the right stuff, inspiring generations of scientists, engineers and astronauts who will take us to Mars and beyond – not just to visit, but to stay.” The quest to broaden that group to include people who don’t look like Glenn, but who aspire to his highest goals has become a national priority. NASA has diversified the astronaut corps significantly since the heyday of Projects Mercury and Apollo, and has taken conscious steps to make the agency more inclusive overall. Meanwhile, a much wider spectrum of positive STEM role models exists today both in real life and mass culture.

The excitement of a Mars mission featuring a diverse set of heroes might be just the ticket America needs to inspire a new generation of children to reach for the stars. Fill out your application here.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.