Even When He Was in His 20s, Winston Churchill Was Already on the Verge of Greatness

The future Prime Minister became known throughout Britain for his travails as a journalist during the Boer War

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/be/ec/beec06c9-dc0b-4a18-affd-763a7d617e8d/3.jpg)

Winston Churchill was on the run. He’d just escaped from a military prison in South Africa, throwing himself over a fence and into some bushes, where he squatted, hiding from his captors. He landed much too close to a well-lit house full of people. Worse, just yards away, a man was smoking a cigar— a man, he knew, who wouldn’t hesitate to shout for the armed prison guards.

So Churchill, then just 24 years old, remained motionless, trusting the darkness and shadows to hide him. A second man joined the first, also lighting up, each facing him. Just then, a dog and cat came tearing through the underbrush. The cat crashed into Churchill and shrieked in alarm — he stifled his impulse to yell or jump. The men dismissed the commotion, reentered the house, and Churchill took off for the nearest safe territory which was 300 miles away.

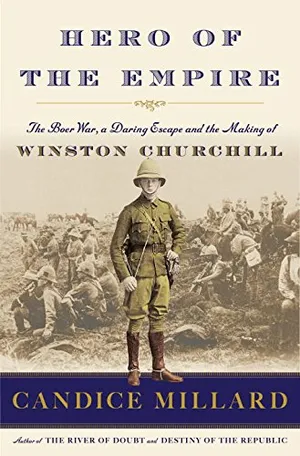

The formative experience of Churchill’s thrilling adventure during the turn-of-the-century Boer War serves as fodder for Hero of the Empire: The Boer War, a Daring Escape and the Making of Winston Churchill, the latest book from best-selling author Candice Millard, a worthy addition to the 12,000-plus volumes already written about the famed British statesman. As with her two previous books, The River of Doubt and Destiny of the Republic about Theodore Roosevelt and James A. Garfield, respectively, Millard has selected a single episode in a long and action-packed life of an iconic figure as her focal point.

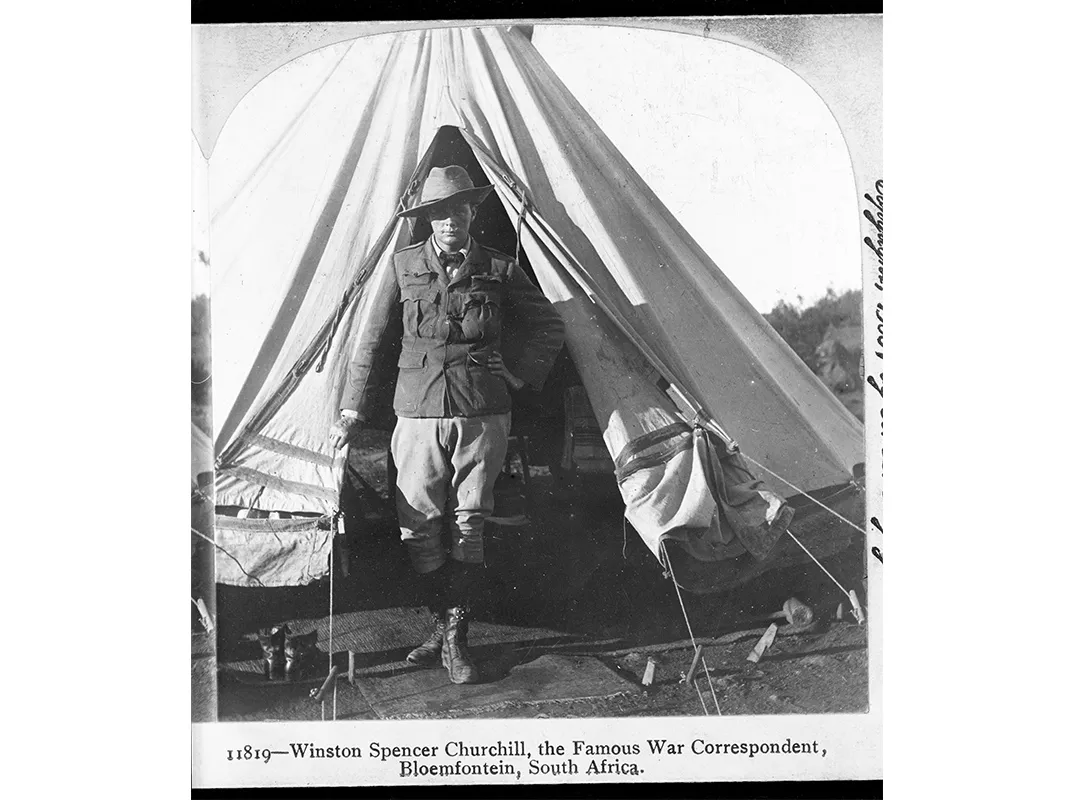

Hero of the Empire centers on Churchill’s stint in South Africa as a war correspondent for London’s Morning Post during the Boer War, which erupted in 1899 after gold and diamonds were discovered in southern Africa. The sought-after resources resided “in the South African Republic, also known as the Transvaal, an independent country that belonged to a group of Dutch, German and Huguenot descendants knows as the Boers,” according to the book. The British Empire wanted to make the land its own, but the white African population held their ground.

Several weeks into the war, Churchill was reporting aboard a train of British soldiers when the Boer army ambushed them and he was taken prisoner. After a month of detention, he made a break for it, riding the rails and hiking through Zulu country. At the lowest point in his journey, Churchill was sequestered in a horse stable in the bowels of a coal mine surrounded by fat, white rats that ate his papers and candles.

“I love to have a narrow story that I can dig really deeply into. I got to talk about South Africa, I got to talk about the Zulu, I got to talk about the Boers, I got to talk about railroads, and coal mines, and all these other things that interest me,” Millard says from one of two light gray leather couches in her office in the suburbs of Kansas City, Kansas.

The former National Geographic writer is unassuming and unadorned in a white T-shirt and baggy blue capris, her dark hair pulled back in a hasty ponytail. Hers is a corner office with two large windows, but the blinds shut out the hot September sun and the rest of the world. When she’s not travelling for research, Millard spends her days here, immersed in another century for years at a time.

Millard chose to tell the story of Churchill’s imprisonment and escape during the Boer War not because it’s unknown — very few Churchill stones have been left unturned. And she didn’t simply choose it so that she could talk about the railroads and coal mines, or Boer leader Louis Botha or visionary Solomon Plaatje, who founded the South African Native National Congress and spent a good deal of time observing and writing about the British army’s then-failing tactics -- though she allows many pages for them, too. Her reason, it seems, was at once grander and humbler than all that: to explore the basic humanity that dwells in even the greatest figure. She explains, “Garfield called it ‘the bed of the sea’ — when someone is ill or desperate, everything’s stripped bare. You see their true character. You see their true nature. That’s always stayed with me, that phrase, ‘the bed of the sea.’”

She says of writing about Churchill’s escape, “So much of who he was and who he became came through at this time and at this moment of danger and desperation. And all of his audacity and courage and arrogance and ambition comes to light. It really did make him a national hero.” As the son of the Sir Randolph Churchill, once a prominent politician, Churchill had been a high-profile prisoner. His escape was swiftly reported in newspapers on both continents.

“What, to me, was most amazing was that on the outside he looks so different from the Churchill we think of,” she says. “We think of this sort of overweight guy chomping on a cigar, and he’s bald and sending young men into war. And here, you have this young, thin guy with red hair and so much ambition. Inside he was fully formed. He was the Winston Churchill we think of when we think of him.”

Even so, throughout Hero of the Empire, Millard portrays Churchill as a fairly irritating upstart who couldn’t be trusted with plans for the prison break. According to her research, Churchill’s friend and fellow prisoner of war, British officer Aylmer Haldane, had “strong reservations about attempting to escape with him.” Churchill was known to have a bad shoulder, but in addition to that, she writes, “While the other men in the prison played vigorous games … to keep themselves fit, Churchill sat before a chessboard or stared moodily at an unread book. ‘This led me to conclude,’ Haldane wrote, ‘that his agility might be at fault.’”

But worse than the physical strikes against him, Churchill had little discretion, loved to talk, and, Haldane felt, “was constitutionally incapable of keeping their plans secret.”

This is the chatty, out-of-shape character Millard shows hiding in the bushes with “£75, four slabs of melting chocolate and a crumbling biscuit” in his pockets. The description of him only grows more pitiful when she references the wanted poster the Boers eventually issued. Aside from a regular physical description, they added: “stooping gait, almost invisible mustache, speaks through his nose, cannot give full expression to the letter ‘s,’ and does not know a word of Dutch … occasionally makes a rattling noise in his throat.” This is the boy who is alone and 300 miles from the safety of Portuguese East Africa, now Mozambique, the Transvaal’s closest neighbor and closest unguarded neutral territory.

While the journey that followed his escape was fraught with ordeals, he also had the stupendous luck of encountering the British operator of a German-owned colliery who was willing to risk his own life to see Churchill to safety. The Boers considered Churchill’s recapture a top priority and launched a door-to-door campaign over several hundred square miles which made him something of an international celebrity--the locals determined to catch him, the British thrilled that one of their own was eluding capture. Only hours after he reached the British consulate, armed Englishmen gathered on the lawn, waiting to escort him to British territory.

“He said, after he won his first election right after he got back from South Africa, that [he won] because of his popularity,” Millard says. The Empire had lost battle after battle to an enemy they had anticipated defeating with ease. Churchill’s successful evasion rejuvenated British hopes of victory.

Millard’s skill at humanizing larger-than-life figures like Roosevelt and Churchill, not to mention her deft aggrandizement of a lesser-known man like Garfield, reveals her literary wizardry. But she says that’s just a product of using a lot of primary sources. “It’s very, very important to me that people know absolutely everything is factual. That’s why I say you can go back and look for yourself.” Her notes pages exhaustively cite sources for every quotation and detail.

Millard also travelled to South Africa and retraced parts of Churchill’s route with John Bird, a local Churchill enthusiast who managed the coal mine at Witbank until his retirement. “He showed me, ‘I think that’s the hill where [Churchill] hid, and he was waiting for the sun to go down so he could get some water. I think he must have gotten water right here,’” Millard says. The two emailed for years, and Bird proofed large portions of her manuscript for accuracy.

It was there on the African veld, waiting for the sun to set, that we see Churchill as most human. “His famously strident confidence had left him, leaving behind only the impossibility of finding his way to freedom, or even surviving the attempt … desperate and nearly defeated, Churchill turned for hope and help to the only source he had left: his God,” Millard writes.

The author glances at the table filled with black and white 8x10s of her visit to the Amazon’s River of Doubt during her Roosevelt research. While she was writing about Roosevelt’s near-loss of his son Kermit on that expedition, her own child was gravely ill. “I was so desperate and so scared, and you suddenly feel this connection to this larger-than-life person,” she says quietly. “But you live long enough and you’re going to have those moments of self-doubt or fear or sorrow or grieving or simply desperation. And I did absolutely sense that with Churchill when he’s on the veld. When he’s alone, he’s scared, he’s got no help, he’s lost hope, he doesn’t know what to do and he doesn’t know where to turn, he gets down on his knees and prays for guidance. I think that’s incredibly relatable.”