The Evolution of the Nurse Stereotype via Postcards: From Drunk to Saint to Sexpot to Modern Medical Professional

A postcard exhibit at the National Library of Medicine shows how the cultural perception of nurses has changed over the decades

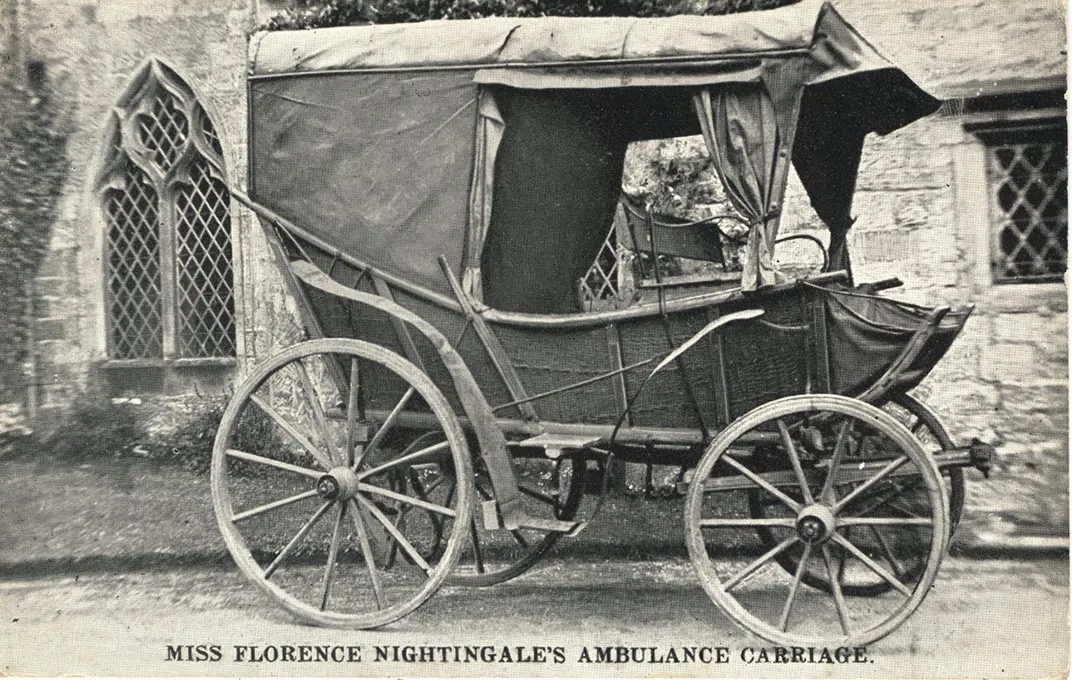

Florence Nightingale knew how to work the press. The Times first painted her as an iconic female healer—the “lady with the lamp”—for her work in the Crimean War in the 1850s. Nightingale used her nursing image to drive public health legislation and improve sanitary conditions in the British army.

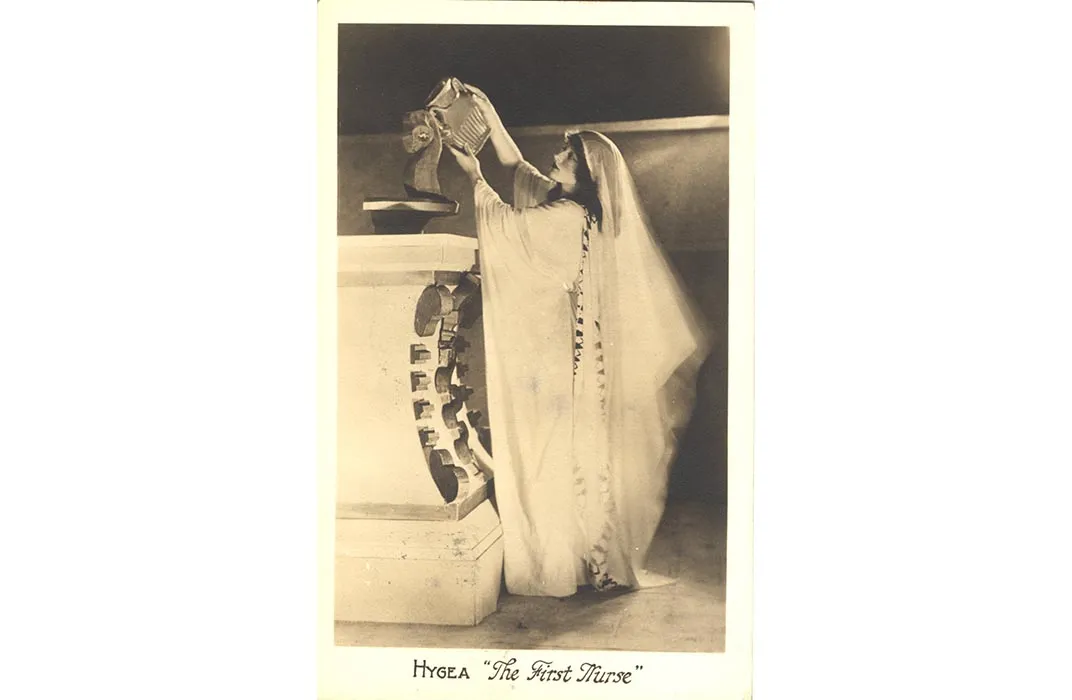

But, the basic image wasn’t necessarily new. “The nurse as a symbol of health—good health—dates back to ancient times,” says Julia Hallam, a professor of film and media at the University of Liverpool who curated a new exhibit on nursing at the National Library of Medicine in Bethesda, Maryland. “Pictures of Nursing” opened earlier this month with a guest lecture from Hallam. The exhibit covers nurses of all varieties, ethnicities and genders through what, to some, might seem an unorthodox medium: the postcard.

“The postcard is a very fleeting art form, and one that in the age of electronic communication—email, twitter, selfies, Flickr, and Instagram—looks ever more anachronistic,” says Hallam. Today, postcards have been relegated to documenting exotic vacations. But, in their heyday at the turn of the 19th century, postcards were all the rage, an easy way to keep in touch without having to write a lengthy letter.

First patented in the U.S. in 1861, early postcards featured printed images of drawings, paintings and comics. With the rise of personal cameras, “real photo” postcards became all the rage. As a result, postcards can provide a snapshot (both literal and figurative) of popular culture.

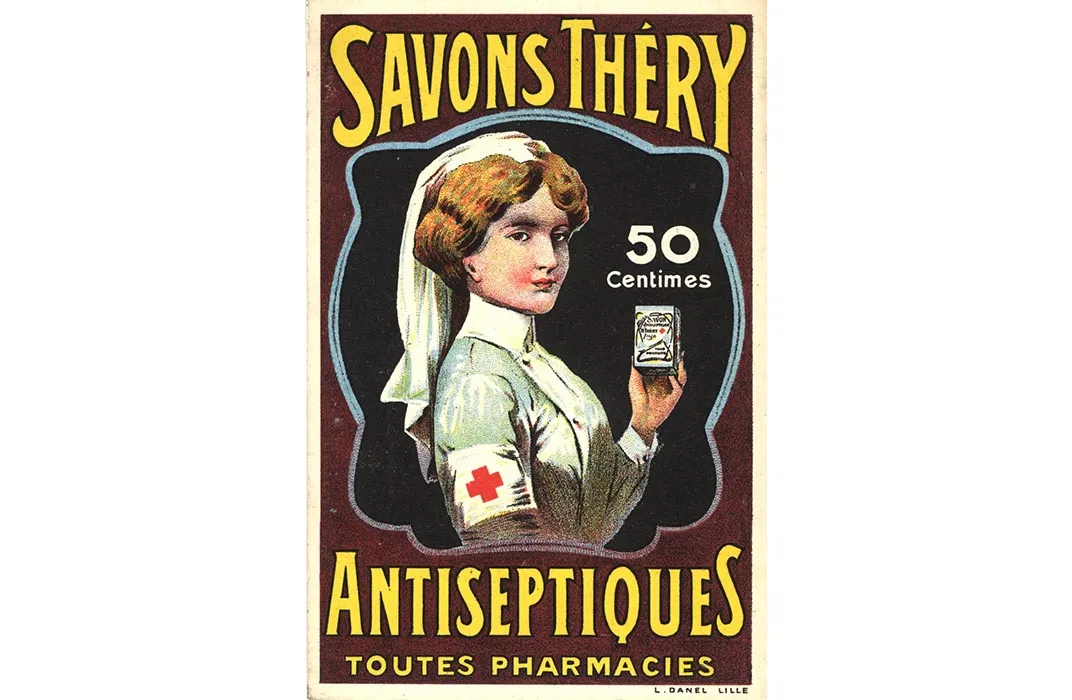

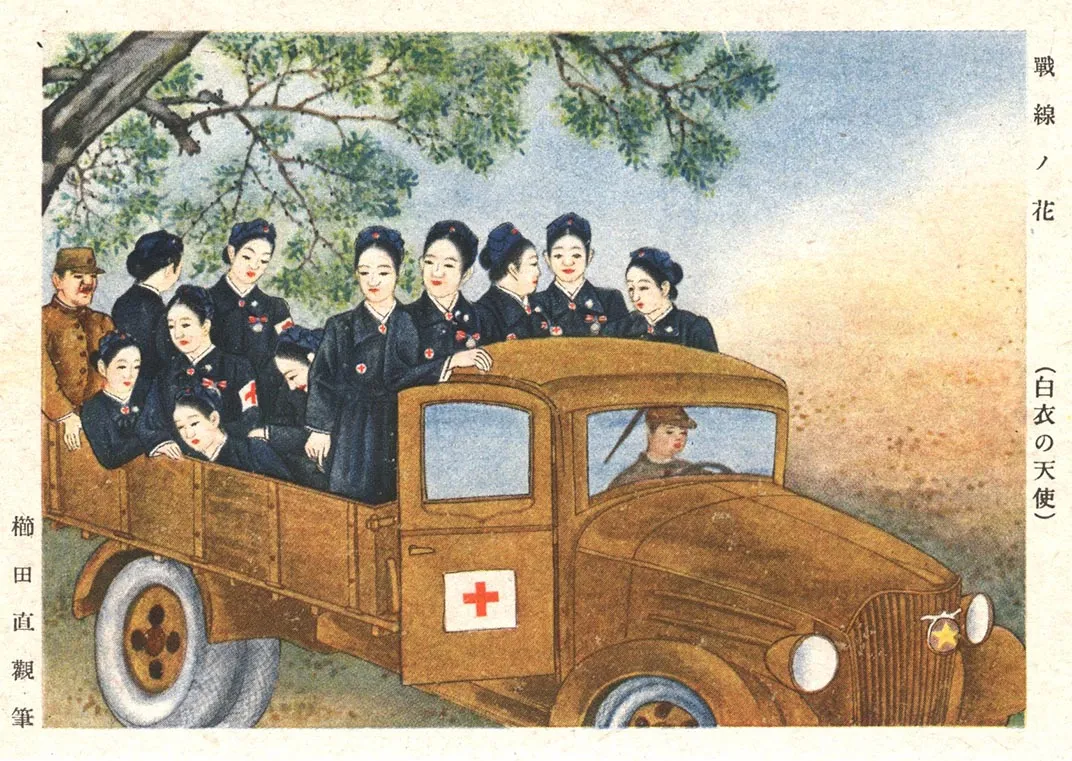

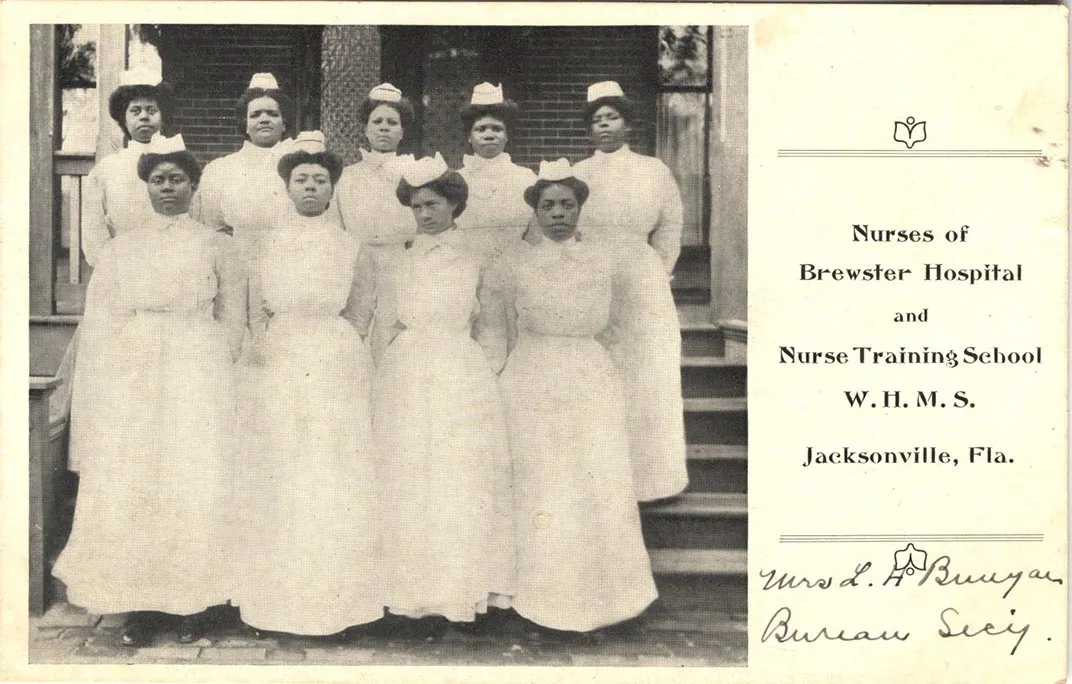

Over the years, postcards depicting nurses were used as recruitment tools, fundraising, advertising and even propaganda. The current exhibit draws from the NLM’s collection of 2,588 postcards produced between 1893 and 2011, donated by former nurse and collector Michael Zwerdling.

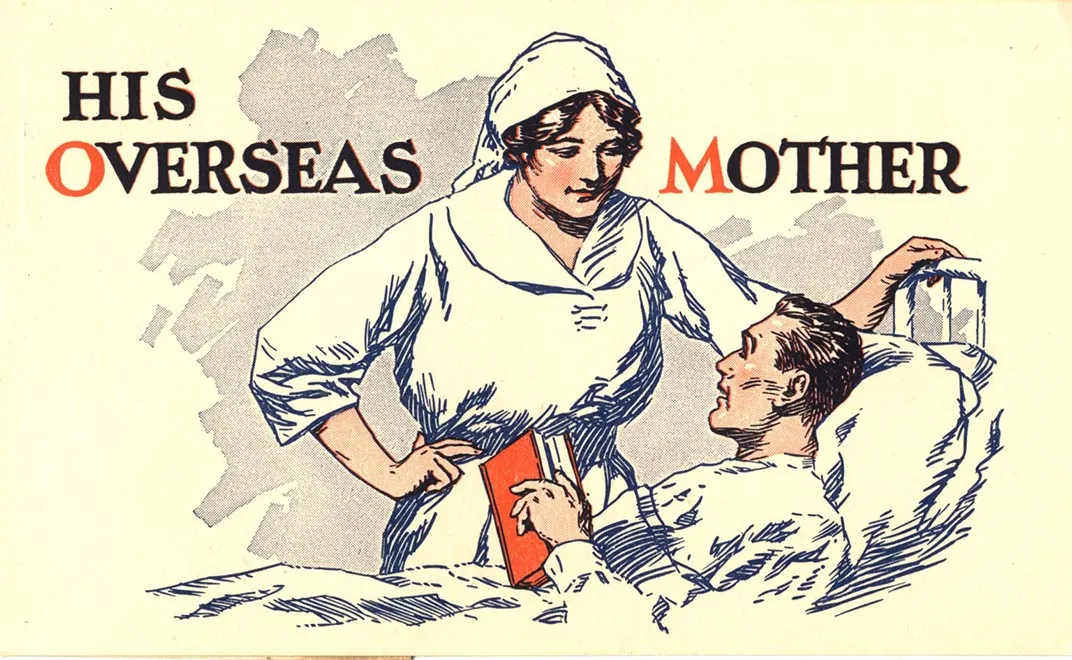

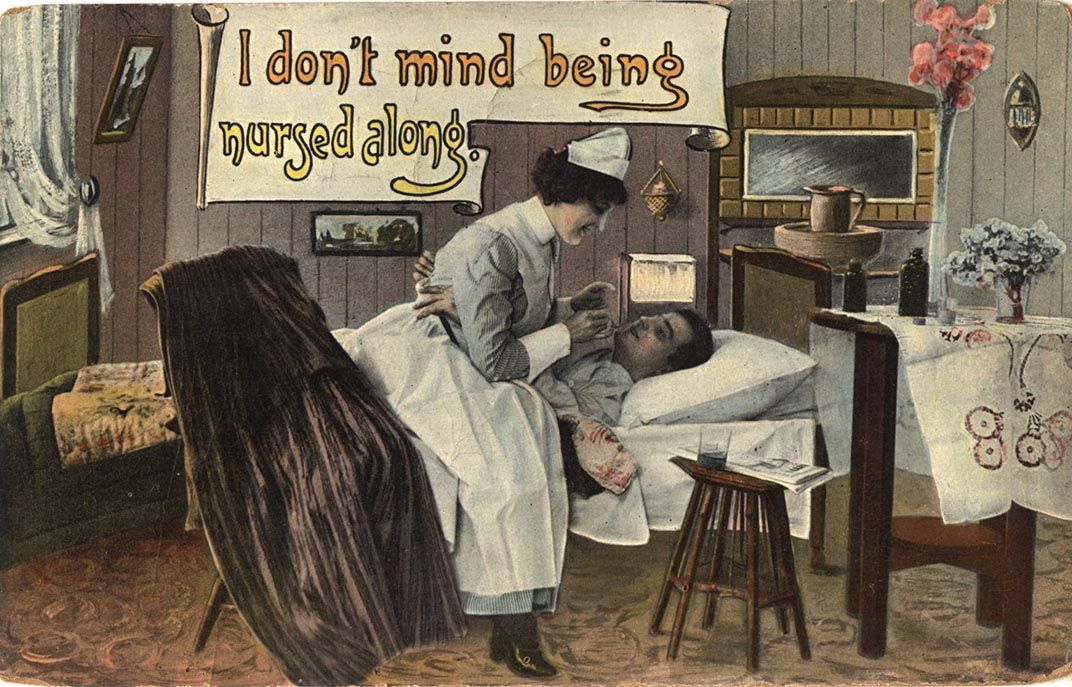

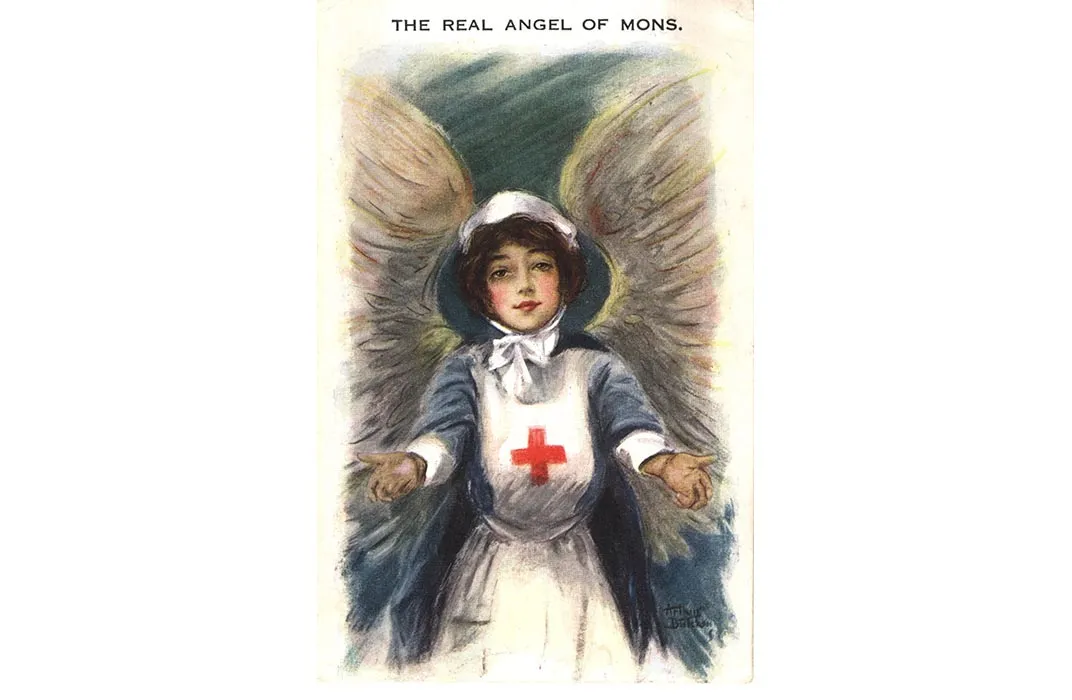

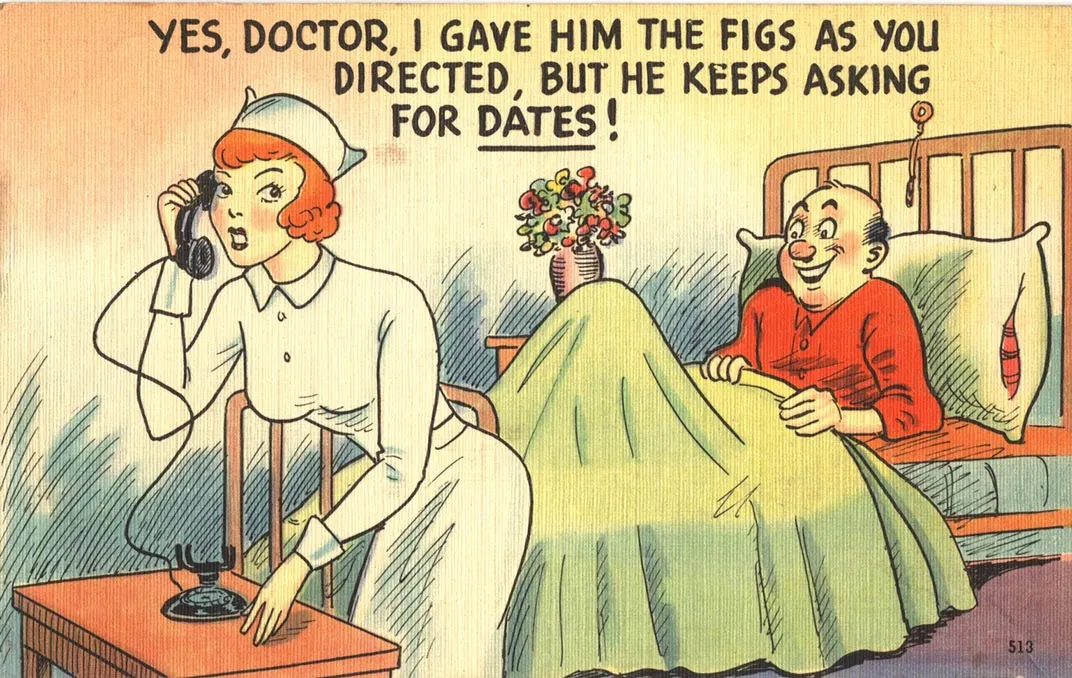

“In selecting the cards, I wanted to communicate a history of nursing that placed it in the context of rapid changes in society and gave birth to modern professional nursing and the gendering of the profession,” says Hallam. From sexualized pin-up images of the 1950s and 1960s to fierce patriots during wartime to angelic matriarchs of the Victorian era, the postcards portray a pantheon of nurses in popular culture through comics, paintings and photographs.

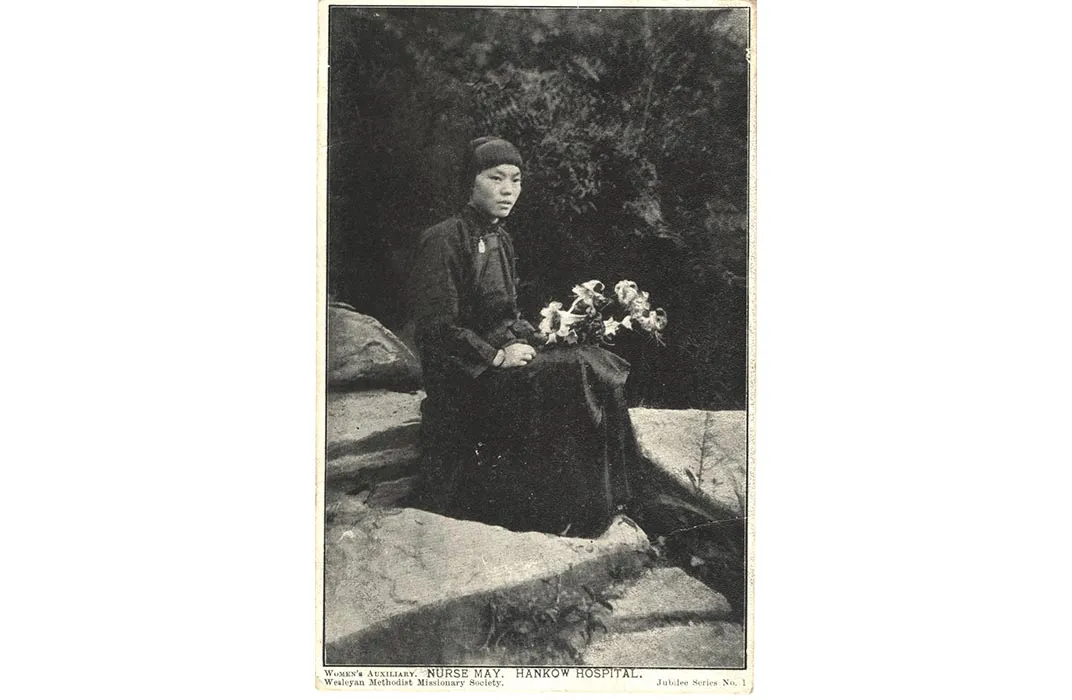

Nursing didn’t truly become a day job until the late 19th century, thanks in large part to the work of pioneers like Nightingale, Clara Barton and Dorothea Dix. “The idea of nursing as a professional vocation captivated the imaginations of young women, not only in Britain but around the world,” says Hallam.

In addition to setting up a training school in London, Nightingale “wrote letters constantly—the equivalent of an email lobbyist today,” says Hallam. (Perhaps modern nurses could learn a thing or two about how to use media to one’s advantage from their enterprising Victorian predecessors.)

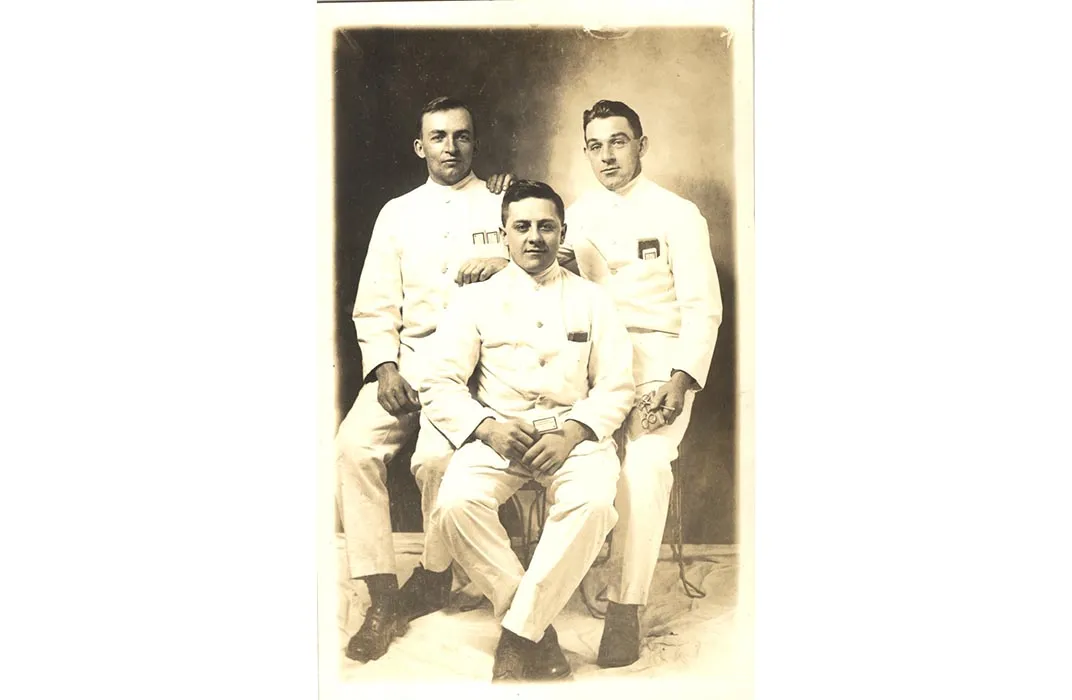

By the early 1900s, nurses had a distinct stereotype: feminine, middle class, Christian and white. This played into Victorian ideals of femininity and imperialism. The sacrifices of military nurses like Edith Cavell, executed by German troops in Belgium during World War I, only added to this image. Popular culture ignored nurses who didn’t fit these criteria. The exhibit shines a light on rarely seen images of male nurses, nurses from minority populations in the United States, and women training to be nurses under colonial rule.

Pictures of private nurses at the turn of the century were decidedly less flattering—frequently drunk with loose morals and of a lower social class. “It’s an image that represents a fear of disease, contagion and a fear of the knowledge, of the physical work associated with nursing,” says Hallam.

As if it wasn’t already governed by contemporary gender roles, nursing became entrenched as a distinctly female profession in the 1920s and 1930s. Male doctors drew strong lines between nursing and medicine, and this pervaded popular culture. “Female stars of stage and screen played nurses, while men are courageous soldiers and handsome doctors,” notes Hallam.

The heroic work of nurses during World War II shifted public perception in the United States, but in the 1950s and 1960s, television shows also helped to cement the stereotype of the sexy nurse. “The images certainly get racier and the innuendo that we see on cards from an earlier period becomes more explicit,” says Hallam.

By the 1980s, nurses were actively trying to upend such imagery, and they’ve been successful for the most part. The few modern recruitment postcards in the exhibit feature nurses of all genders, races and classes. That said, nurse stereotypes are still ingrained in our popular culture—every modern Halloween costume shop carries a sexy nurse costume.

Rather than wax nostalgic about the past, Patricia Tuohy, the NLM’s head of exhibition programs, hopes that visitors come away “thinking critically about where those images come from, what they mean and what that might mean for nursing today.”

“Pictures of Nursing” is on view at the National Library of Medicine through August 21st, 2015, and the exhibit’s online gallery features 585 additional images to explore.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)