An Exclusive Look at the Greatest Haul of Native American Artifacts, Ever

In a warehouse in Utah, federal agents are storing tens of thousands of looted objects recovered in a massive sting

At dawn on June 10, 2009, almost 100 federal agents pulled up to eight homes in Blanding, Utah, wearing bulletproof vests and carrying side arms. An enormous cloud hung over the region, one of them recalled, blocking out the rising sun and casting an ominous glow over the Four Corners region, where the borders of Utah, Colorado, Arizona and New Mexico meet. At one hilltop residence, a team of a dozen agents banged on the door and arrested the owners—a well-respected doctor and his wife. Similar scenes played out across the Four Corners that morning as officers took an additional 21 men and women into custody. Later that day, the incumbent interior secretary and deputy U.S. attorney general, Ken Salazar and David W. Ogden, announced the arrests as part of “the nation’s largest investigation of archaeological and cultural artifact thefts.” The agents called it Operation Cerberus, after the three-headed hellhound of Greek mythology.

The search-and-seizures were the culmination of a multi-agency effort that spanned two and a half years. Agents enlisted a confidential informant and gave him money—more than $330,000—to buy illicit artifacts. Wearing a miniature camera embedded in a button of his shirt, he recorded 100 hours of videotape on which sellers and collectors casually discussed the prices and sources of their objects. The informant also accompanied diggers out to sites in remote canyons, including at least one that agents had rigged with motion-detecting cameras.

The haul from the raid was spectacular. In one suspect’s home, a team of 50 agents and archaeologists spent two days cataloging more than 5,000 artifacts, packing them into museum-quality storage boxes and loading those boxes into five U-Haul trucks. At another house, investigators found some 4,000 pieces. They also discovered a display room behind a concealed door controlled by a trick lever. In all, they seized some 40,000 objects—a collection so big it now fills a 2,300-square-foot warehouse on the outskirts of Salt Lake City and spills into parts of the nearby Natural History Museum of Utah.

In some spots in the Four Corners, Operation Cerberus became one of the most polarizing events in memory. Legal limitations on removing artifacts from public and tribal (but not private) lands date back to the Antiquities Act of 1906, but a tradition of unfettered digging in some parts of the region began with the arrival of white settlers in the 19th century. Among the 28 modern Native American communities in the Four Corners, the raids seemed like a long-overdue attempt to crack down on a travesty against their lands and cultures—“How would you feel if a Native American dug up your grandmother and took her jewelry and clothes and sold them to the highest bidder?” Mark Mitchell, a former governor of the Pueblo of Tesuque, asked me. But some white residents felt that the raid was an example of federal overreach, and those feelings were inflamed when two of the suspects, including the doctor arrested in Blanding, committed suicide shortly after they were arrested. (A wrongful-death lawsuit filed by his widow is pending.) The prosecution’s case was not helped when its confidential informant also committed suicide before anyone stood trial.

Ultimately, 32 people were pulled in, in Utah, New Mexico and Colorado. None of them were Native American, although one trader tried vainly to pass himself off as one. Twenty-four were charged with violating the federal Archaeological Resources Protection Act and the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, among other laws. Two cases were dropped because of the suicides, and three were dismissed. No one went to prison. The remainder reached plea agreements and, as part of those deals, agreed to forfeit the artifacts confiscated in the raid.

The federal Bureau of Land Management (BLM), which has custody of the collection, spent the last five years simply creating an inventory of the items. “Nothing on this scale has ever been done before, not in terms of investigating the crimes, seizing the artifacts and organizing the collection,” BLM spokeswoman Megan Crandall told me. Before they were seized, these objects had been held in secret, stashed in closets and under beds or locked away in basement museums. But no longer. Recently the BLM gave Smithsonian an exclusive first look at the objects it has cataloged.

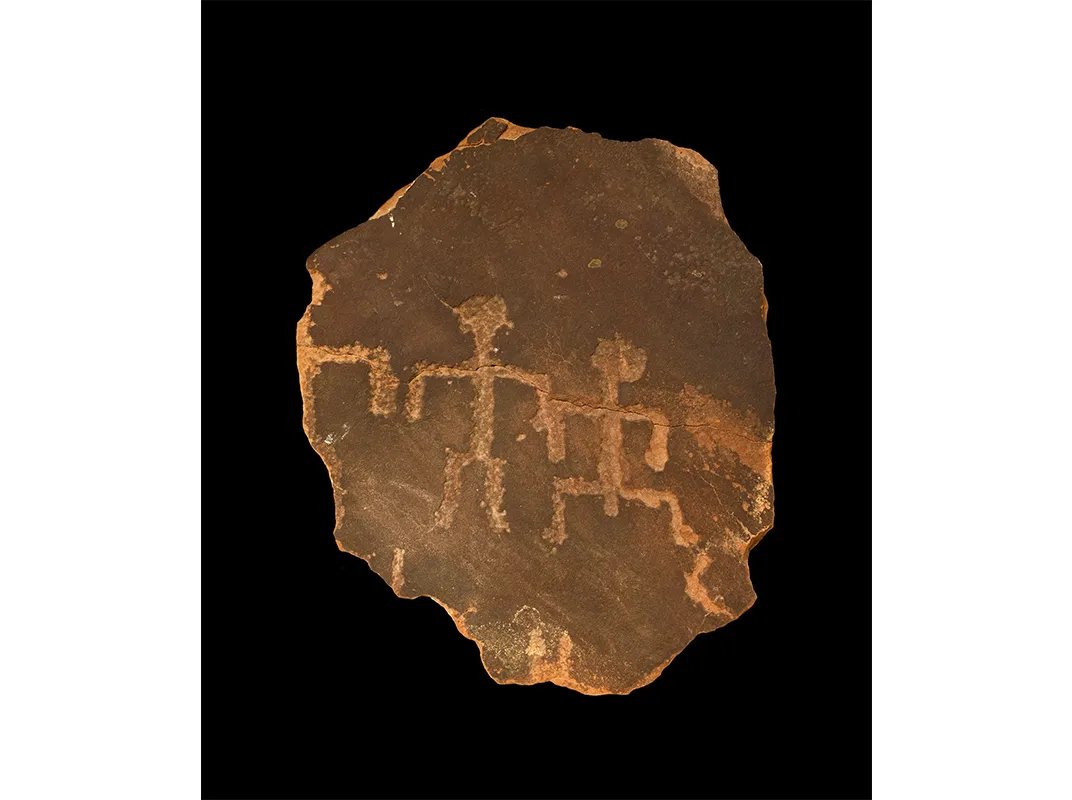

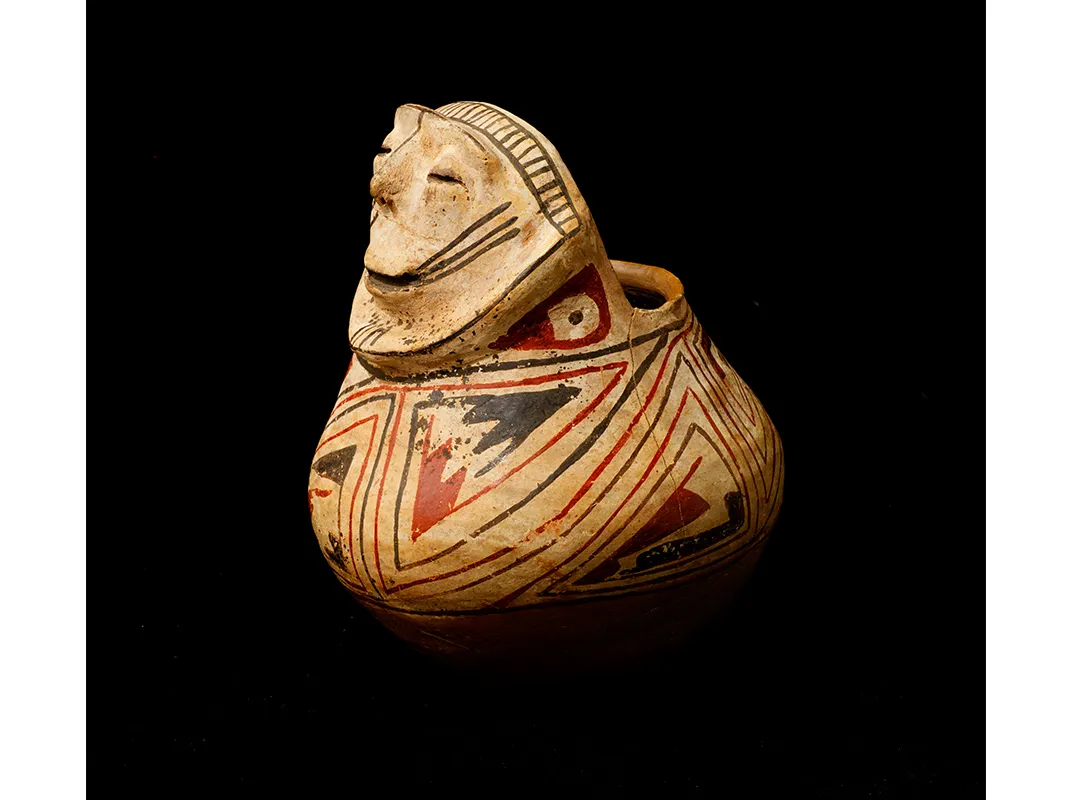

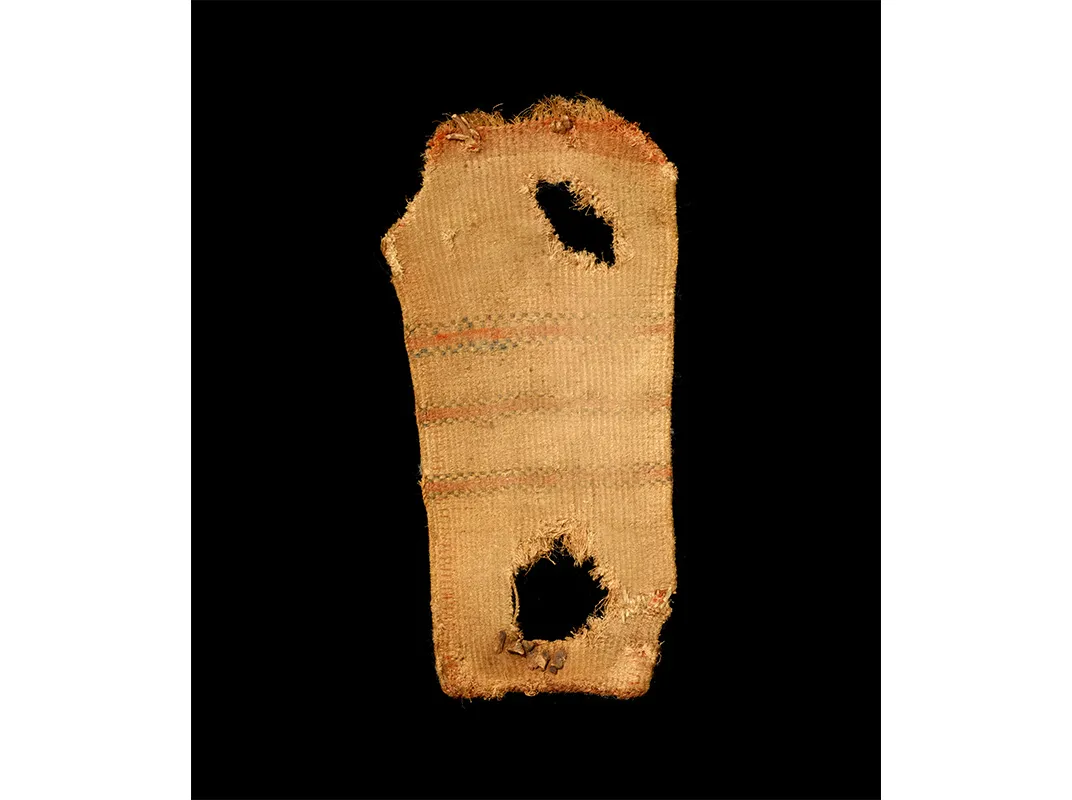

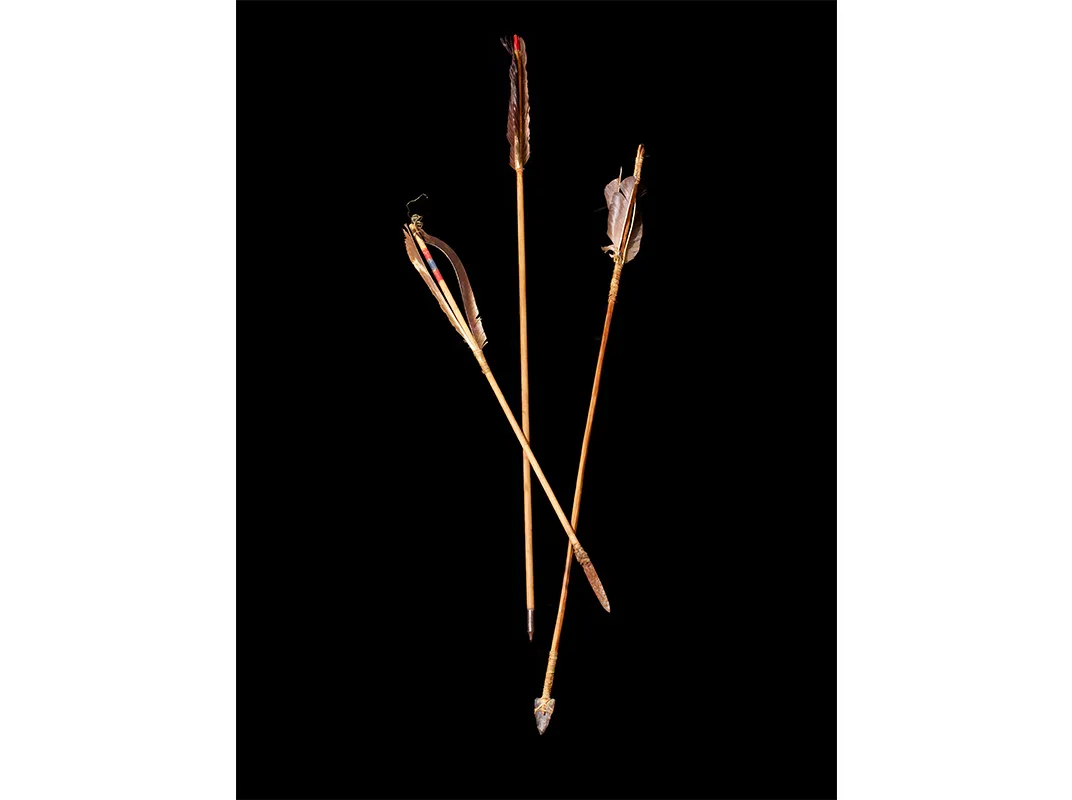

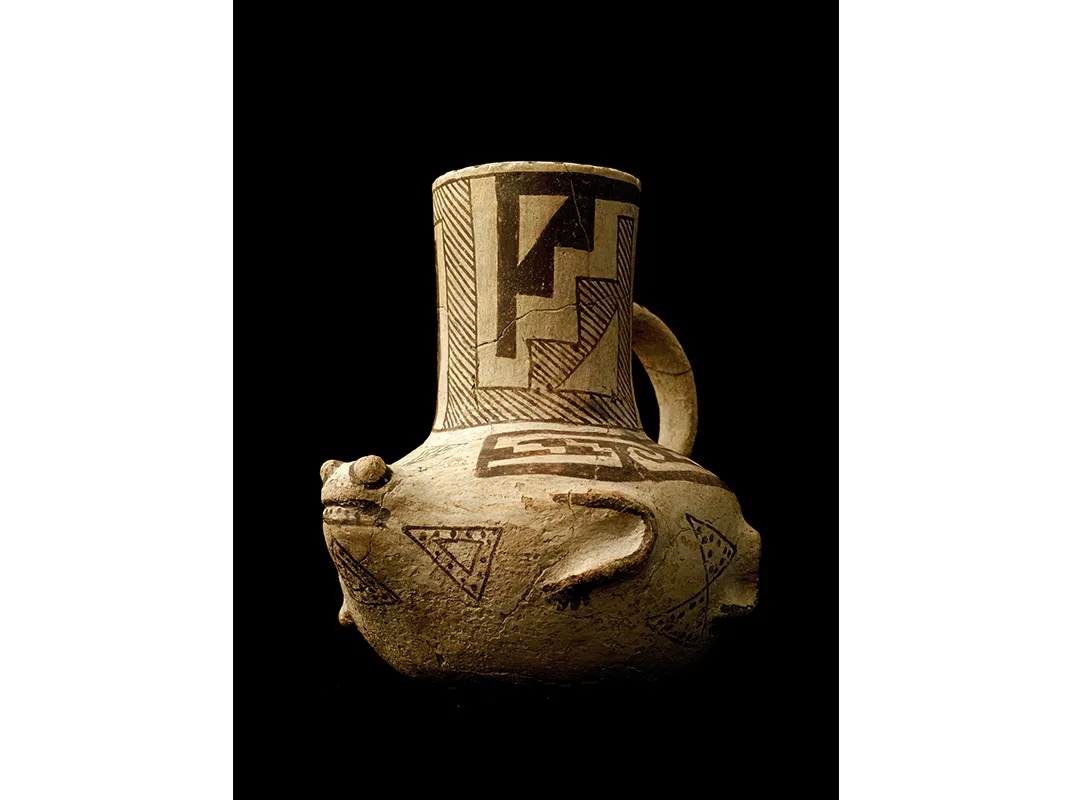

Beyond the sheer size of the collection is its range: Some of the objects, such as projectile points and metates, or grinding stones, date to about 6,000 B.C. Among the more than 2,000 intact ceramic vessels, many appear to be from the Ancestral Puebloan people, or Anasazi, who lived on the Colorado Plateau for some ten centuries before they mysteriously departed around A.D. 1400. The Hohokam, who occupied parts of Arizona from A.D. 200 to 1450, are represented by shell pendants and ceramic bowls; the Mogollon, who thrived in northern Mexico and parts of Arizona and New Mexico from A.D. 300 to 1300, by pottery and painted arrow shafts. An undated sacred headdress belonged to the White Mountain Apaches, while a buffalo mask from the early 20th century is being returned to the Pueblo people in Taos. “You won’t find some of these items anywhere else,” said Kara Hurst, who was a curator of the BLM trove for three years until 2013, when she became supervisory registrar at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. “We’ve heard stories about some of these objects. But not even Native Americans had seen some of these things before.”

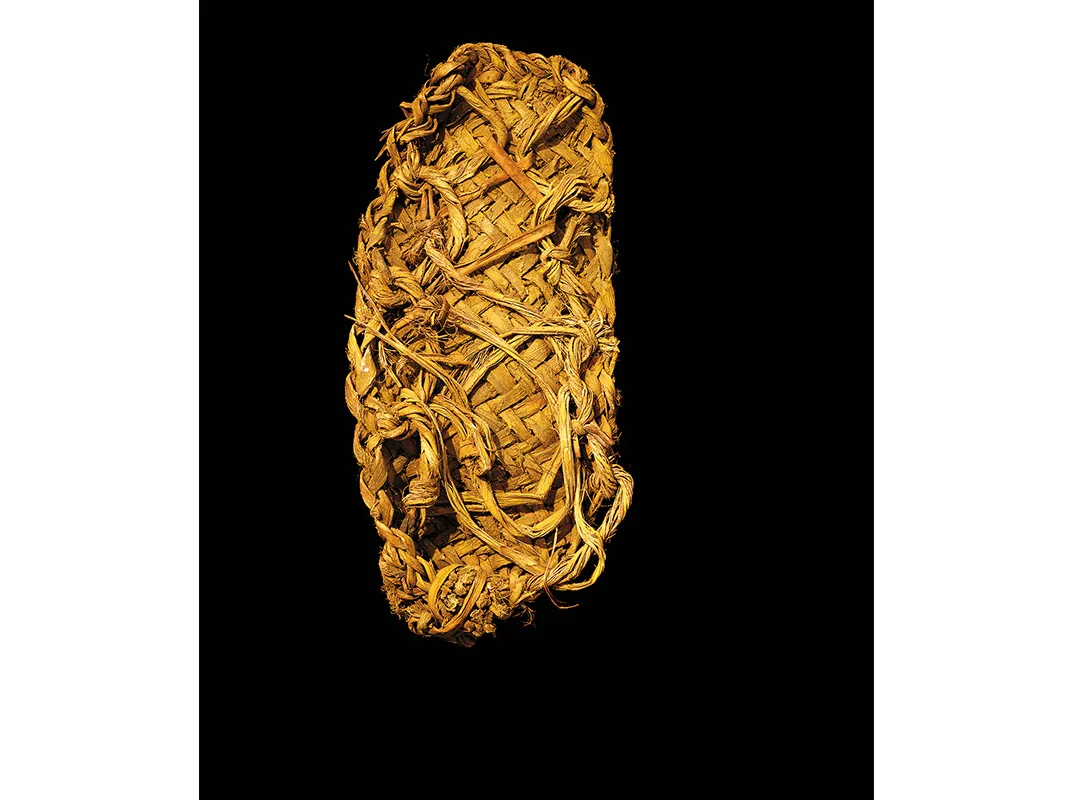

It’s possible that no one will be able to see them outside the Cerberus collection, because archaeologists today rarely dig in the alcoves and cliff dwellings from which many items were taken. “There’s no money to support legitimate excavations of alcoves today,” said Laurie Webster, a research associate at the American Museum of Natural History who specializes in Southwestern perishable objects. “So you’ll never be able to excavate artifacts like these again.”

Many of the artifacts are remarkably well-preserved, even though they’re composed of delicate materials such as wood, hide and fiber. That’s partly a testament to the desert climate of the Four Corners—but also an indicator that at least some of the objects may have come from caves or other well-protected funerary sites, which has been a source of particular anguish to Native peoples. “The dead are never supposed to be disturbed. Ever,” Dan Simplicio, a Zuni and cultural specialist at Crow Canyon Archaeological Center in Cortez, Colorado, told me.

Roughly a quarter of the collection has high research potential, according to a preliminary survey by Webster. At the same time, the mass of objects is an archaeologist’s nightmare, because so many lack documentation of where and in what context they were found. “Stolen pieces usually don’t come with papers unless those papers are hot off the printer,” Crandall said.

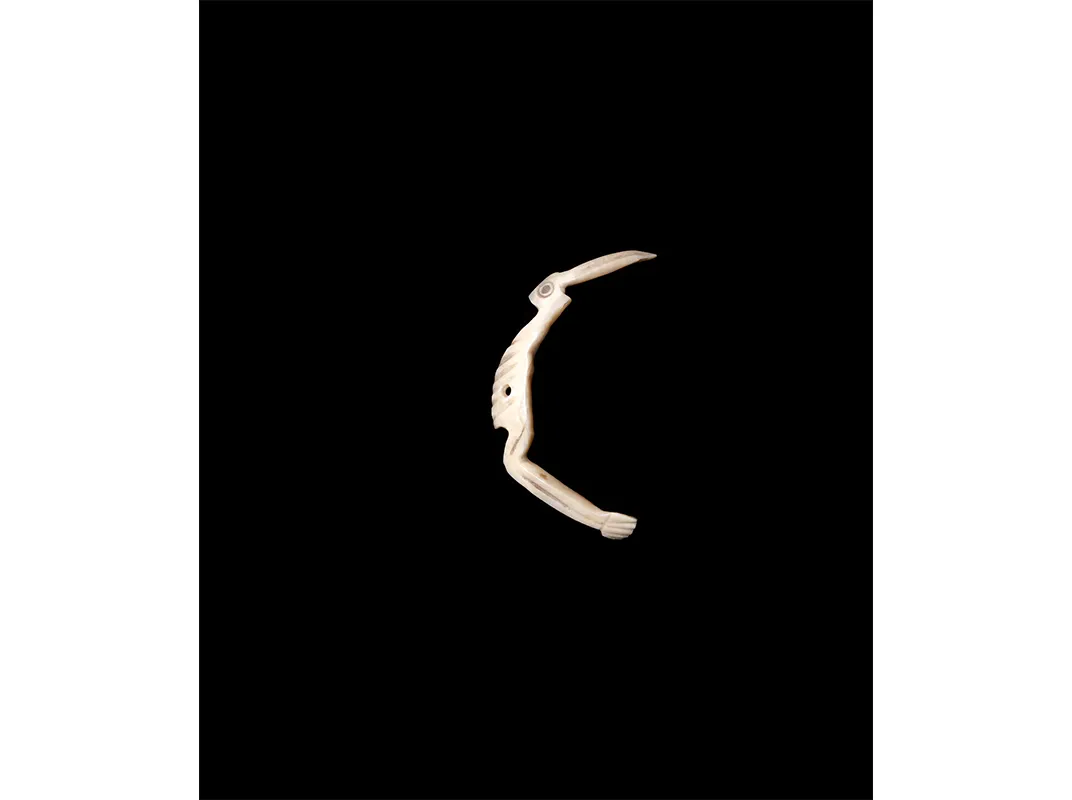

In some cases, it’s not clear whether the relics are even genuine. Two human effigies, about six inches tall and made of corn stalk, yucca cordage and wood, are a case in point. One has an oversize erection, while the other has a dent between the legs. A dealer called them “fertility figures,” labeled them as from southeastern Utah, and dated them to about 200 B.C. to A.D. 400.

Webster had never seen any figures like them before, and she initially thought they were fakes. But on closer inspection she saw that the yucca cordage appears to be authentic and from somewhere between 200 B.C. and A.D. 400. Now, she believes the figures could be genuine—and would be of extreme cultural value. “This would be the earliest example of a fertility figure in this region,” said Webster, earlier than the flute-playing deity Kokopelli, who did not appear until about A.D. 750. To investigate this artifact further, scholars will have to find their own research funds.

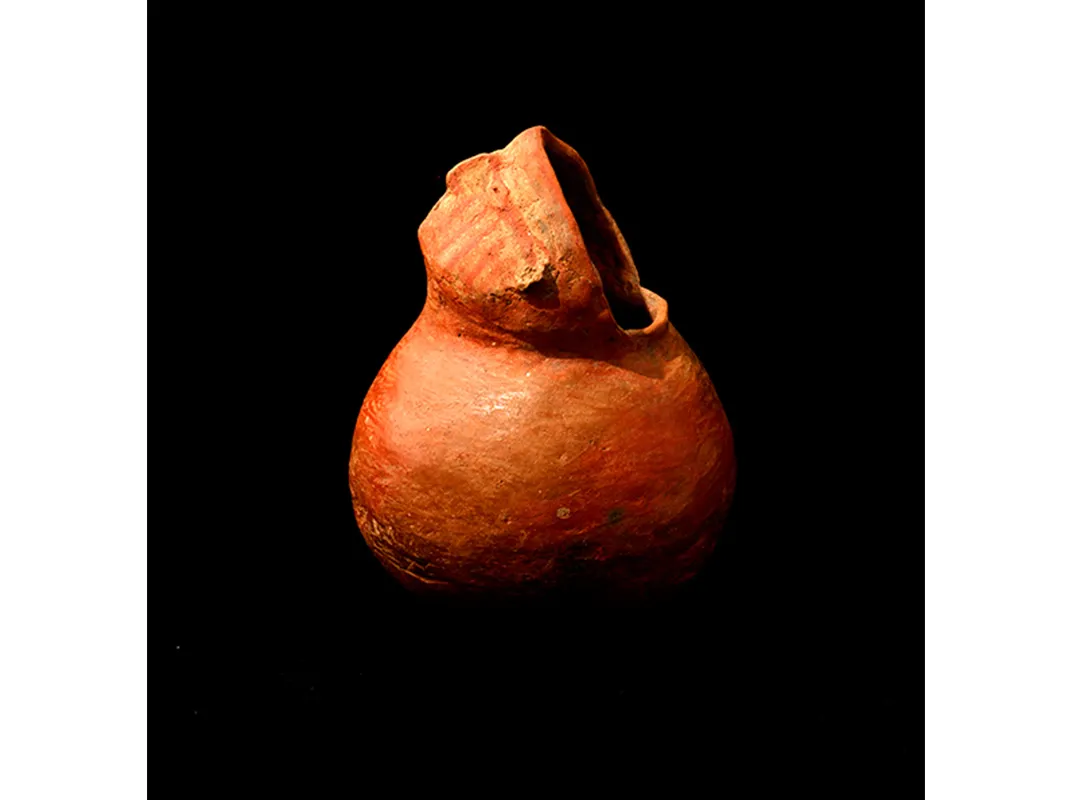

A multicolored ceramic bowl tells a more bittersweet tale. The exterior is the color of a flaming desert sunset, and the interior features bold geometric shapes and black and red lines; it is clearly in what archaeologists call the Salado style, a genre that appeared around A.D. 1100 and blended elements of Anasazi, Mogollon and Hohokam pottery. The piece was slightly marred by a few cracks, but more damaging are the “acid blooms” inside the bowl—evidence that someone used a contemporary soap to clean away centuries of dirt. The idea is that restored or “clean” vessels will fetch more money on the black market, said Nancy Mahaney, a BLM curator. “It’s been very interesting to work with the collection, because you can see the extent to which people will go to gain financially.”

With its inventory done, the BLM will give priority to returning whatever objects it can to the tribes from which they were taken. Even though the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act has highly specific guidelines for repatriating artifacts, several experts in the Native American community said the process will be complicated by the lack of documentation.

Once the BLM’s repatriation effort is complete, which will take several more years, the agency will have to find homes for the artifacts that remain. It hopes to form partnerships with museums that can both display the artifacts and offer opportunities for scholars to research them. “Part of our hope is that we will form partnerships with Native American communities, especially those that have museums,” said Mahaney. The Navajo have a large museum, while the Zuni, Hopi and others have cultural centers. Blanding, Utah, where several of the convicted looters live, has the Edge of the Cedars State Park Museum. Even so, it will take years of study before the Cerberus collection begins to yield its secrets.

Plunder of the Ancients